Gagaku

Gagaku ( Japanese 雅 楽 , "elegant music") is a courtly style of music that has been played at the Japanese imperial family since the 7th century and especially since the Heian period . The Gagaku originally comes from the Chinese Empire . The style consists of chamber music , choral and orchestral music . In Japan this music partly has cultic tasks.

Gagaku was named an Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO in 2009 .

History of the Gagaku

Gagaku is the Sino-Japanese reading of Chinese yayue, first found in Lunyu, the analects of Confucius from the beginning of the 5th century BC. Can be proven. Yayue denotes traditional ritual or elegant, refined music. In the latter sense, it was adopted into Japanese and is used today for the traditional music of the Japanese imperial court, especially the Nara and Heian periods . In addition, Shinto ritual music falls under the term Gagaku. This music called kagura ( 神 楽 ) is probably the oldest component of the Gagaku repertoire and as such is very likely autochthonous Japanese.

The genesis of the kagura has not been passed on, but grave finds from the Yayoi period (approx. 300 BC to approx. 300 AD) have been preserved, which prove that burials were celebrated with song and dance. Figurine finds made of clay pottery, so-called haniwa , from the Kofun period (approx. 300 to approx. 645 AD) show musicians playing instruments, including flutes, drums and stringed instruments that are reminiscent of European zithers . The oldest Japanese chronicles, the Kojiki (712 AD) and the Nihongi (720 AD), also refer to music as part of burial and coronation ceremonies. Both works consider music to be a gift from the gods, played to appease them. It is therefore likely that the kagura had a long-lasting musical tradition at that time, i.e. at the beginning of the Nara period.

In Chinese sources from the 3rd century AD, there are indications that Japanese ambassadors only came to the Tang Court sporadically , but maintained lively contacts with the three Korean kingdoms Paekche , Silla and Koguryō . In the course of these contacts, Korean musicians, who were already influenced by Chinese music, were sent to Japan to perform their art, which was called sankangaku ( 三 韓 楽 , English: music of the three Koreas ) in Japanese, and Japanese Teaching students. A Korean orchestra was even maintained permanently in Japan from around the 5th century. Towards the end of the 7th century, the power of the Tennō was largely consolidated and the imperial court established constant diplomatic contacts with the court of the Tang Dynasty in China. In addition to the numerous other achievements of Chinese culture - including writing , language and philosophy - the music and dance of the Tang court also penetrated Japan over the course of a maximum of 200 years and met with a wide response from the aristocracy . This style, which is more likely known in China as banquet music, eventually established itself in a slightly adapted form as specifically Japanese court music. Students were sent to China and Chinese musicians came to Japan; Around 700 the Gagakuryō or utamai no tsukasa (Imperial Music Office) was founded by Emperor Monmu (697 to 707), which was responsible for the various groups of musicians and their care. An inheritable musicianship was introduced, the line of which has remained unbroken to this day through the adoption of capable musicians into the responsible clans.

In the course of these reforms, the instrumentation was standardized and the styles were given their names that are still valid today: tōgaku ( 唐 楽 ) for music from China and komagaku for Korean music. Probably there are also some pieces of Southeast Asian and Indian origin under tōgaku ; Similarly, the Komagaku repertoire includes Manchurian compositions and Chinese pieces that have been rewritten for the Korean ensembles. Japanese musicians also composed in the style of these two major categories, so that today no exact dividing lines can be drawn. On the part of the Gagakuryō, great care was taken to ensure that the musicians only cared about the care of their own musical assets, a mixture of the different directions was deliberately avoided. Isolated sources say that in 736 an Indian and an Indochinese monk visited Japan to present music and dance from their respective homeland. According to records, a cultural highlight in all of East Asia was the opening ceremony of the eyes of the Great Buddha at Tōdai-ji in Nara in 752, during which Japanese, Korean and Chinese - possibly even Indian and Southeast Asian - music and dances were performed. 17 of the more than 30 instruments that were used at this great event are still preserved and are kept in the imperial treasury of the Shōsōin in Nara. With the help of these carefully crafted and richly inlaid instruments, it is also possible to examine the high level of craftsmanship of that time.

Heian period

In the Heian period (794 to 1185) the culture of Gagaku, which now functioned as a collective term for this multitude of styles that were gradually Japaneseized, flourished. The repertoire and number of professional musicians who had to organize themselves into clans were streamlined and standardized. The abdicated Tennō Saga (786 to 842), who ruled from 809 to 823 as the 52nd Tennō , played a key role in these reforms. It is thanks to him that the Gagaku ensemble in the form we know today. The gagaku enjoyed increasing popularity among the nobility. One began to play instruments, to compose and to perform music, which was soon an integral part of court life. The Genji monogatari (tale of Prince Genji) from the beginning of the 11th century by the lady-in-waiting Murasaki Shikibu gives an illustration of the musical activities of the nobles at this time .

Kamakura time

With the decline of the aristocratic court culture in the Kamakura period (1185 to 1333) came a noticeable decline in the popularity of the gagaku. The practice of Gagaku was restricted to a small group, for example to the musician clans who were deprived of their livelihood and the closest imperial court. Since the performance possibilities were very limited, many shrines and also some Buddhist temples were used by the musicians as performance venues. The clans of professional musicians were in Osaka , Kyōto and Nara and existed in relative isolation from one another. This inevitably prevented further development of techniques and compositions; the knowledge of the performance practice of numerous works was lost.

Muromachi period

In the Muromachi period (1333 to 1573) the cultural presence of the Gagaku reached its lowest point. New styles such as the music of the Nō theater , which was co-founded by Zeami Motokiyo (1363 to 1443) around 1400 , displaced traditional music from its traditional place and took over its function as a central cultural event at court. It was only the fact that Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536 to 1598) maintained a standing Gagaku orchestra in Edo that suggested a slow but steady improvement in the desolate situation. Toyotomi gave fiefs to the musicians who could now fully concentrate on their vocation.

Edo period

During the Tokugawa period (1603 to 1868) the kyūdai'e were introduced: exams that every professional musician had to undergo every three years. After the services provided, the fiefs were distributed.

Modern

The Gagaku received widespread attention both by the public and by music research towards the end of the 19th century. From 1873 everyone was allowed to take music lessons; For the first time pieces from the Gagaku repertoire - of which around 90 compositions were still preserved or reconstructed - were performed publicly in their traditional form. Gagakuryō, renamed Gagakukyoku or gakubu, united the three musicians from Nara, Kyōto and Osaka and ordered that each of the imperial musicians also had to "learn a European instrument and play it ... at courtly-representative occasions". As a result, the Gagaku musicians nowadays not only play all traditional court and ritual music, but also give performances of Western classical music - with great success. The members of the imperial ensemble still derive their origins from one of the three great clans and from there to the countries of origin of the Gagaku: the Osaka clan sees their ancestors in China, those from Nara in Korea and those from Kyoto in Japan. The school for gagaku musicians begins with about twelve years; In the ten years up to graduation, the student learns dance, singing and a Japanese string and wind instrument as well as a Western instrument.

Gagaku repertoire

As already mentioned, the Gagaku repertoire today still comprises around 90 compositions. This represents only a fraction of what was once very rich material. There are various theoretical approaches to classifying the pieces that do not belong to the autochthonous Japanese Shinto ritual music. The roughest subdivision distinguishes between danced music, called bugaku (dance and music), and kangen (flute and string), the chamber music of Gagaku, or between material from China, which is summarized under the term tōgaku, and that from Korea komagaku . Of course, the separation can rarely be drawn exactly; in most cases there is overlap. For example, pieces of tōgaku were rewritten for komagaku (and vice versa); Forms of music that came from India, Manchuria or Southeast Asia were arbitrarily assigned to one of the two groups. As early as the 9th century, a distinction between sahō and uhō (left and right music) was introduced, which allowed a clear differentiation that was less related to origin. The reasons for the choice of these names can only be guessed at; probably they relate to the spatial arrangement of the traditional open-air performance area. The emperor always sat there looking south, with Chinese musicians entering from the left, Korean musicians from the right. As will be shown later, this system offers a useful criterion, since the instrumentation of the two directions differs significantly.

The oldest part of the Gagaku are the Japanese ceremonial songs, entitled ōuta , to which there is also dancing. Their origins go back to prehistoric times. The first written mention is in Kojiki , there in a mythological context. Various Shinto deities use music and dance to appease the sun goddess Amaterasu mitmikami, who, insulted by her brother, hid in a cave and thus shrouded the world in darkness. This text describes in detail the instruments that are still used today in rituals and ceremonies. In addition to the mikagura (court kagura), which has the central role, the yamato-uta, the azuma-asobi and the kume-uta fall into this category. In the ideas of Shinto, this music is a sacred sacrifice to the gods or the spirits of deceased people in order to praise them and seek their help ( torimono ) or to entertain them ( saibari ).

The music of the sahō forms the largest group of compositions within the gagaku. Of the well over 100 pieces, around 60 are still preserved today. Their country of origin was mainly China, but also India and Southeast Asia, often in a separate category called rin'yugaku, after a kingdom called Rin'yu (also Lin-yi , Chinese for Champa ). Eight pieces from today's repertoire belong to this category and are characterized by the use of masks that are unusually grotesque for Japanese standards. To sahō belong kangen and bugaku music, as well as the vocal music forms saibara and rōei . Saibara (in German "horse driver music ") are old folk songs, mainly from the areas around Kyoto and Nara, which have been reworked in an artistic sense. They consist of alternating five- and seven-syllable lines of verse and a refrain. In terms of content, they deal with the feelings of ordinary people, preferably with love, which is expressed unusually openly. Saibara were often performed on festive occasions, as is also described in some places in the Genji monogatari . They lost their popularity to the imayō during the Kamakura period . Rōei is a genre in which Chinese and Japanese poems are sung with instrumental accompaniment. In the uhō ( komagaku- ) category there are now only danced pieces ( bugaku ), they come from the three kingdoms of Paekche, Silla and Koguryō in Korea or Manchuria ( bokkaigaku ). Formerly called sankangaku (music of the three kingdoms), it was given the name that is still valid today around the middle of the 7th century AD. In the past, instrumental music in the uhō style ( komagaku-kangen ) was also played. These pieces are only partially preserved today - if at all - as a rule, the missing sections are supplemented by compositions from other origins. The classification, which mostly refers to tōgaku , is based on these set pieces .

Instruments of the Gagaku

In principle, the instrumentation of the Gagaku ensemble is an adaptation of the Chinese court orchestras of the Tang period and their instruments. In the sahō chamber music kangen there are two or three shō (mouth organ), hichiriki (double reed flute) and ryūteki (transverse flute), two gakubiwa (lute) and gakusō or koto ( vaulted board zither) and one kakko (barrel drum), shōko (hanging bronze gong) and taiko (hanging drum). The cast in komagaku is similar to the kangen ensemble, but ryūteki is replaced by komabue (smaller flute ) and kakko by san-no tsuzumi (hourglass drum). The shō and the stringed instruments are omitted here. Compared to the kangen ensemble, the bugaku form does not use stringed instruments in most cases and the shō, shōko and taiko are replaced by two daishōko (large hanging gong) and dadaiko (large hanging drum). In the forms of vocal music, both Japanese and sahō, the wind instruments of the kangen are used, but the only rhythm instrument is shakubyōshi (wooden counterstrike sticks ), which are struck by the group leader.

Shō (mouth organ)

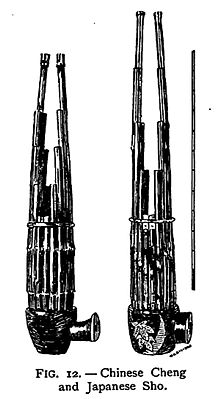

The most unusual instrument in Gagaku for the western observer is the shō , the mouth organ . Its forerunner is the Chinese sheng , which is the oldest polyphonic wind instrument in the world. Chinese legends say that the shape and sound of the instrument were modeled on the phoenix and its scream. In some forms of vocal music and in komagaku, the shō plays the melody; however, its main function is harmonious.

Hichiriki

The hichiriki is a double-reed instrument made of bamboo wrapped in cherry tree bark . There are numerous legends about the instrument in the Japanese tradition. Minamoto no Hiromasa, for example, who came into his house, which had been robbed except for the hichiriki , began to play. The robber heard this and was so moved that he returned and put all the stolen items back in their places. In another legend, the gods are so moved by a hichiriki performance in a temple that they finally give rain to an area whose population has long suffered from drought. The hichiriki also comes from China, where it comes in many sizes. Today's instrument, as it is currently used in the Gagaku, is one of the smallest wind instruments with a length of about 18 centimeters. It has nine holes, two on the bottom and seven on the top. Using special techniques, for example half covering the holes or overblowing, the musician is able to play the ornamentation, grinding and quarter or even eighth notes typical of the hichiriki . The classic way to learn this instrument is to memorize the entire repertoire in a solfège system before engaging with the instrument itself. A whole genre of Gagaku, called imayo, arose from the fact that the solfège was replaced by poetry. The sound of the hichiriki is compared to that of the European oboe , but is, similar to the Indian Shenai, much wider, squat, clearer and stronger. Because of this, the hichiriki, as the main melody instrument, is the heart of the entire Gagaku ensemble.

Accompanying flutes (Ryuteki)

The third wind instrument is a flute, as it is similarly known in the West. The type of flute depends on the music that is being played: in tōgaku it is the ryūteki or yokobue . It is of Chinese origin and has seven holes. The closed end is covered by a piece of red cloth. It is the largest of the Gagaku flutes and the forerunner of the nō-flute ( nōbue ). The komabue is used in komagaku. With six holes it is the smallest flute of the Gagaku, the end of which is covered with green fabric. The function of the flutes in the gagaku ensemble is similar to that of the hichiriki . They follow the melody but vary it slightly. These different variations are called heterophony , which is usually more evident in komagaku than in tōgaku . The kagurabue , which is also part of a kagura ensemble, is a bamboo flute of unspecified length with six holes. It is probably an autochthonous Japanese instrument, but it was exposed to Chinese influence in the Nara and Heian periods.

Gakubiwa

The gakubiwa is a lute with a pear-shaped body. It has four strings and four frets. The strings are only pressed on the frets, not between them, and struck with a wooden plectrum, bachi. The arpeggios (broken chords) end with their highest note on the melody note and mark time segments in the piece. Their function is therefore primarily rhythmic.

Gakuso (zither)

The gakuso is a precursor to the popular Japanese koto . It is a thirteen-string, zither-like instrument, the bridges of which can be variably offset and thus change the mood. The strings, which, with the exception of the lowest, are arranged in ascending pitch, are played with finger picks in the form of leather rings with bamboo tips, as well as with bare fingers. In contrast to the koto, the strings behind the bridges are never pushed down to produce sound fluctuations. The gakuso plays two stereotypical pattern during a performance usually shizugaki and hayagaki called to serve the timing of the piece and thus rhythmic function are.

In some cases, mostly with the vocal music forms of Shinto music, one can also observe the use of the wagon (six-string vaulted board zither) in a gagaku orchestra . The six silk strings of the wagon are struck with a short plectrum. If the music is played outdoors ( tachigaku , "standing music"), so-called toneri hold the wagon for the musician.

Kakko (barrel drum)

The kakko ( barrel drum ) player is the leader of the entire ensemble. Its task is to determine the tempo of the piece, to mark sections and to maintain cohesion in rhythmically free passages. The drum itself consists of a relatively small, flat arched, horizontally mounted resonance body, which is covered with deer skin on both sides. As with the hourglass drum janggu, the skins are connected and tensioned with ropes. The kakko player sits on the broad side of the instrument and plays with his sticks on a skin. The kakko characters include drum rolls and single beats that are played with one or both sticks and help to stabilize the slow rhythm.

In komagaku , the slightly larger san-no tsuzumi takes on the role of kakko . Its hourglass-shaped body is covered on the top and bottom, the tension is ensured by ropes like the kakko . The musician hits only one side with his sticks. In ancient writings one found indications that there were once four different hourglass drums that were played with bare hands, only the san no tsuzumi remains.

Shōko (gong)

Main article: Shōko

The gong , Japanese shōko , appears in three different sizes in the gagaku, depending on where it is used. The smallest is in the tōgaku ensemble, the largest ( daishōko ) in bugaku outdoors. It is made of bronze and is played with two hardwood sticks. Its job is to emphasize the first beat of every measure; in the fourth measure there is a serve.

Taiko (barrel drum)

Main article: Taiko

The taiko is the largest drum in the Gagaku orchestra. It can be found as a ninai-daiko , which is worn in parades, or as a tsuri-daiko , which is played hanging on a stand. Although two sides of the narrow body are covered, only one is struck with two sticks with a leather head. The bass drum is a colotomy instrument, which means that its rhythmic phrases are used to underline and separate larger sections of a piece. In bugaku, the dadaiko, the very large drum , is used instead of the taiko . It fulfills a choreographic rather than a musical task; their stroke serves to emphasize the dancers' footsteps. This drum is hung in a large, splendidly lacquered frame. The structure is similar to that of the taiko, only that the skins do not consist of one piece, but are made up of several pieces. A head alone would not be able to hold enough tension to produce a sound. The drum is tuned by turning wooden stakes around which the ropes that are used to stretch the skins on the front and back of the body are wound. The drum is struck with two heavy sticks made of lacquered wood, always in the order left - right.

Performance practice of the Gagaku

The performance practice of the gagaku depends primarily on the origin of the repertoire. During instrumental concerts, the musicians sit on a stone or wooden stage, which is surrounded by a railing and raked gravel and which can be set up both outdoors and in closed rooms. Her clothing consists of simple silk robes in a dark rust brown. Green vertical threads are worked into the fabric so that the robes shimmer when you move.

If bugaku dance music is performed, the ensemble sits next to or behind the stage. The clothes of his musicians are more colorful and splendid than in the kangen. The dancers wear free-falling, dragging costumes that are modeled on court fashion of the Heian period. Their basic principle is to wear several silk kimono, whereby the lower ones at the hem protrude as a narrow strip over the upper garments. In the warrior dances ( bu no mai ) the wide sleeves and trouser legs are tied to allow more freedom of movement; a black brocade cape and a heavy metal belt are also worn. The artists wear headgear for some performances: black, stiffened hats or hoods and white, the dancers white silk shoes ( shigai ) and, depending on the dance, masks. Depending on the origin of the dances, the carefully woven, richly decorated robes are red in the sahō no mai and green in the uhō no mai. According to this criterion, the direction of stepping onto the stage and with which foot the dance is started also depends. In a concert consisting of four to six pieces, the compositions of left and right music appear in pairs and are played alternately. At the end of the performance, after the dancers and musicians have left, music "to round off " ( taishutsuraku ) is played in the adjoining room or in a separate area, the akunoya (green room) . On occasions when sacred Shinto music, such as the mikagura, is played, the musicians wear monochrome white, sometimes red or blue robes in the style of the Heian court. The mood on such occasions is emphatically serious and solemn, and the musicians behave accordingly. Mikagura is only played at the emperor's court shrine in his presence. The oldest form of this music provides for the consecration of a sacred area, the summoning of the deity, ceremonial eating and drinking as well as the performance of dance and music. This ceremony used to take days; today it has been shortened to around six hours and a total of eleven songs and dances. A more recent form of mikagura, as mentioned in a source from AD 807, is a chinkon dance performed annually by women . In the old folk belief it is possible through this dance to bring the soul of a recently deceased back into their body.

Formal structure of the gagaku

All compositions of the Gagaku are performed at a very slow pace for western ears. The melody is primarily carried by the wind instruments or the singing voices. String instruments act as a kind of link between their harmonies and the rhythm of the percussion instruments, which is played in fixed, repetitive patterns that are "all terminologically classified". Even if the melody instruments are based on the rhythm, it is still possible for them to break away from it, i.e. to play more or less asynchronously. Towards the end of a piece, however, they always fall back into the given rhythm. The “embedding of the melody between the shō sounds floating above and the foundations of the broken string instruments rising from the depths below” is one of the central concepts of the Gagaku formalism, on which a large part of the magic of this music is based.

The works of Shinto music are, in terms of their formal structure, the simplest matter of Gagaku. Since they are mainly songs, the human voice and the sung lyrics are in the foreground. The instruments are used as accompanying instruments, be it to set the pitch for the singers, to play short introductions or to anchor and strengthen melody and rhythm. The harmonies are “original Japanese” and were hardly influenced by ideas from the continent.

Scales and modal system

The most complex formal structure can be found in tōgaku and thus also in saibara and rōei . It is based on the Chinese untempered modal system ( see also the tone system of Chinese music ). This means that if you add successive fifths to a root note ( superimposition ), the resulting thirteenth note does not correspond to the root note. Its pitch is a little different from the first according to the Pythagorean comma . On each of the twelve tones within such a circle of fifths , scales of seven tones, five main and two secondary tones, are built up, which are divided into ryō and ritsu according to their mood . Depending on which of the five main tones is started, there is a different mode of the scale (Japanese: chōshi ).

The multitude of scales was never exhausted; In the Tang music system, 28 scales were used, in tōgaku only six pieces: ichikotsuchō, hyōjō, sōjō, ōshikichō, banshikichō and taishikichō . The number of six chōshi is deceptive and imprecise in that they, with the exception of hyōjō and sōjō , also contain compositions that have been transposed into other modes and thus represent practically independent compositions, so-called watarimono (transitional pieces ). There are series of special ornaments , moods and tone ranges that are different and typical for each chōshi ; they can hardly be compared with mere scales in the western sense.

Therefore, the mode must first be specified when giving a presentation . This is done through introductions, which are called " netori " in tōgaku and komagaku and are played in free rhythm before the actual piece. The form of these preludes is determined by tradition: the Shō begins, a short time later the hichiriki begins, then ryūteki and kakko play a short duet, with koto and biwa at the end . In bugaku these preludes are called chōshi and are longer and more complex; they are not only played at the beginning, but also between the individual sections. This polyphonic “planned chaos” is laid out in threefold canon form .

Six netori and six chōshi are still in use today. The pieces of tōgaku are divided according to length into shōkyoku (short), chūkyoku (medium) and taikyoku (large pieces).

rhythm

The rhythmic theory of the gagaku is a little less complicated. For slow pieces that will nobebyoshi for medium speed the hayabyoshi and faster compositions the osebyoshi used. This division is similar to the western 8/4, 4/4 and 2/4 bars . It is possible to change time signatures within a piece; these pieces are called tadabyoshi . Fast tadabyoshi are mainly used in bugaku and then possibly mixed with yatarabyoshi (3/4 time).

Sound systems in Komagaku

In komagaku three different existing sound systems : coma ichikotsuchō, coma Sojo and coma hyōjō . Almost all pieces are composed in the first two tone systems. Formally, they derive from the Chinese modal system, but in terms of harmony they are more reminiscent of kagura chants. The melody instruments, hichiriki and komabue , are run independently here; this results in a polyphony that is not present in the tōgaku to this extent.

Aesthetic Principles of Gagaku

Every Gagaku piece begins "with a single flute, the other wind and percussion instruments only start on the second beat of the big drum and the stringed instruments start a little later". Towards the end of the performance, some instruments stop prematurely (tomede); During the Heian period, amateur musicians contested the final sections without competition from professional musicians and were thus able to demonstrate their skills. Most compositions contain numerous repetitions of one or more themes that are slightly varied or canonically displaced by different instruments. Roughly speaking, a piece has the form netori - theme A - theme B - theme A - tomede. In no case do the musicians have the freedom to improvise and in the rarest cases are the rules prescribed by tradition capable of interpretation.

The dissonances that are particularly noticeable to the Western music listener, the now and then hardly discernible cohesion between rhythm and melody, the absolute formalism of even the smallest note, all this is the work of generations of professional musicians who have tried since the Nara period to bring the musical quintessence of Gagaku into an increasingly refined form.

The central point of the aesthetic sense of self of the Gagaku is the conception of the jo-ha-kyū. It says that a slow introduction (jo) is followed by a faster, longer middle section or an exposition (ha) and the piece ends with a rapid, abrupt end (kyū). These three sections within a composition also follow the jo - ha - kyū scheme. In longer compositions, a fourth section, the ei, is inserted between ha and kyū, while the introduction can be omitted in short pieces. This system is not only specific to Japan in terms of music theory; it also plays a central role in the nō and bunraku theaters. The roots of this aesthetic concept lie in China; it was adopted in the Heian period and written down towards the end of that period. It was further developed by the aforementioned Zeami Motokiyo and his students.

glossary

- Bu no mai ( 武 の 舞 ): "warrior dance"; Category of fast, relatively wild dances of the bugaku

- Bugaku ( 舞 楽 ): "Dance and Music"; Dance theater with music, partly masked

- Bun no mai ( 文 の 舞 ): "civil dance"; Category of slower dances of the bugaku

- Chinkon ( 鎮 魂 ): "appease spirits"; Shinto ritual, in which the soul of a person is prevented from leaving the body or is moved to return to the body

- Dōbu ( 童 舞 ): children's dance

- Enkyoku ( 宴 曲 ): Banquet music, also mockingly called enzui ("drunken pond"); the melodies have been lost, we have received some rather crude collections of texts

- Gagaku ( 雅 楽 ): "elegant music"; Generic term for Japanese concert and court music

- Gigaku ( 伎 楽 ): Chinese mask dances , which reached Japan around 600 via Korea, were lost in the Edo period , texts, masks and influences are still preserved today in popular lion dances , instrumental accompaniment consisting of flutes, hourglass drums and cymbals

- Hashiri-mai ( 走 り 舞 ): "running dance"; corresponds to bu no mai

- Hira-mai ( 平 舞 ): "even dance"; corresponds to the bun no mai

- Imayōuta ( 今 様 歌 ): "contemporary songs"; song type created by replacing the solfège of Gagaku compositions with poems; other sources name the hymns of Buddhist priests who proselytized among prostitutes as their origin

- Kagura ( 神 楽 ) "sacred music"; the court kagura (in contrast to sato kagura, village kagura) is the ritual Shinto music of the imperial court

- Kangen ( 管絃 ): "Wind instruments and string instruments"; Chamber music , today exclusively in the tōgaku style

- Komagaku ( 高麗 楽 ): later name for Korean music, named after the Kingdom of Koma ( Goryeo )

- Kudara-gaku ( 百 済 楽 ): Music style introduced around 550 from the Kingdom of Kudara ( Baekje ) in Korea

- Miasobi / Gyōyu ( 御 遊 ): "court player"; Heian Court amateur orchestra

- Rōei ( 朗 詠 ): Short Chinese-style poems that are sung with instrumental accompaniment

- Saibara ( 催馬 楽 ): Folk songs in a modified, made acceptable form with a syllable text that is now incomprehensible

- Sankan-gaku ( 三 韓 楽 ): "Music of the three Korean kingdoms "; Collective term for music in the Korean style

- Shiragi-gaku ( 新 羅 楽 ): Music style introduced around 450 from the Kingdom of Shiragi ( Silla ) in Korea

- Tōgaku ( 唐 楽 ): " tang -time music"; Collective term for music in the Chinese style

- Wagaku ( 和 楽 ): "Japanese music"; Pieces composed by Japanese musicians

Individual evidence

literature

- Horst Hammitzsch : Japan manual . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1990, keyword "Gagaku music".

- Eta Harich-Schneider : Rōei. The Medieval Court Songs Of Japan . in Monumenta Nipponica . Tōkyō 1958, 60.

- Eta Harich-Schneider : The Rhythmical Patterns in Gagaku and Bugaku . Brill, Leiden 1954.

- Kaneo Matsumoto (Ed.): The Treasures of the Shōsōin. Musical Instruments, Dance Articles, Game Sets . Kyoto 1991.

- Pierre Landy: Les Traditions Musicales. Japon . Buchet / Chastel, Berlin 1970.

- William P. Malm: Japanese Music and Musical Instruments . Charles E. Tuttle, Tōkyō 1959.

- Organizing Committee for the Games of the XVIII. Olympiad (Ed.): Gagaku Art Exhibition during the Tōkyō Olympics 1964 . Tōkyō 1964.

Web links

- Yonei Teruyoshi: "Gagaku" . In: Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugaku-in , February 20, 2007 (English)

- Cologne Gagaku Ensemble - the only practicing Gagaku orchestra in Europe.