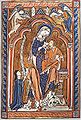

Maria lactans

Maria lactans (also: Galaktotrophousa , Mlekokapitelniza , Breastfeeding Mother of God , Blessed Loss ) describes the motif of the breastfeeding Maria .

Religious historical background

The image motif already appears in ancient Egyptian culture, where the goddess Isis breastfeeds the Horus boy , which not only points to the general theme of maternal fertility , but is also related to royal theology (Assmann 1984). Horus is the mythical archetype of the legitimate king, who is understood as "Horus on the throne". Isis, whose name means “seat of the throne”, is not only the maternal protector and breadwinner in this context, but also transmits divine powers to her son with her milk. It is therefore not surprising when Egyptian kings were represented on the breasts of Isis and other goddesses: with the divine milk, the infant receives divine essence from the nursing mother. Corresponding representations can be found in Amenhotep III. , with Hatshepsut (on both Brunner 1986) and many others. The nursing mother is often Isis, but also Hathor (especially in Hatshepsut's million year house in Deir el-Bahari ) and other goddesses are depicted as dea lactans , sometimes in the form of a cow.

In Greek culture, the motif appears in the Herakles tradition. Heracles is mistakenly breastfed by Hera , but sucks so hard that the goddess throws him off his chest. Their abundant divine milk creates the Milky Way . Heracles, however, has already absorbed so much of the divine power that he can now accomplish his superhuman exploits. In the Roman area, the topos appears as an explicit reception of Egypt, namely in the text of the Domitian obelisk, which the emperor had built in the new complex of the Iseum Campense .

Christian motif story

The ancient Egyptian motif tradition is taken up by Coptic (= Egyptian) Christianity and reinterpreted within the framework of Christian dogmatics. Despite dogmatic efforts to emphasize the humanity of Mary's milk (see below), the early Coptic depictions of Maria lactans continue the pictorial tradition of Isis lactans . Corresponding evidence can be found as wall paintings and reliefs in monk cells and monastery churches, v. a. from the 7th / 8th Century AD. Before that, however, the Isis temple at Philae was converted into a Christian church, whereby the reliefs that show Isis with the Horus boy seem to point to Mary and Jesus, which is why they remained largely undamaged - quite the opposite to other representations of gods. In addition, the motif is documented with papyrus PSI 1574 for the 6th century. The theme runs in numerous variations through Christian art history up to the present and is documented for the Eastern Churches as well as for the West and Latin America. One of the earliest Christian statues of a breastfeeding Madonna is believed to be the Nossa Senhora da Nazaré (Our Lady of Nazareth) in Nazaré , Portugal, from the first millennium .

The Lactatio Bernardi represents an important extension of the motif : based on a vision narrative, Bernhard von Clairvaux is shown how his lips are moistened with Mary's breast milk. This helps him to be eloquent. This type of image is also documented for other male saints, e.g. B. for Petrus Nolascus . This paves the way for representations that allow all believers to share in the divine milk of Mary. A representation of Nicola Filotesio (called Cola dell'Amatrice ) shows Mary relieving the agony of the poor souls in purgatory .

The late medieval / early modern cult of milk relics (Schreiner 1994) is also based on the opening of the lactatio to all believers. The baroque well chapels / well statues also presuppose this extension of the lactans motif. In the fountains of some pilgrimage sites, the healing water is directed through the breasts of the figure of Mary and symbolically becomes the divine milk of Mary, which is accessible to all pilgrims. Through the holy milk of the Blessed Mother, everyone who seeks salvation attains redemption, so the message of this construction. To be found in the pilgrimage church Mariahilf above Passau , in the spring of Rengersbrunn , in Maria Ehrenberg , in the well chapel called the Bründl in Brunnenthal , or on the Marienbrunnen Großgmain , where a double-figure Maria sprinkles water from four breasts at the same time.

In the case of lactation difficulties or mastitis , it was customary in some regions to pray in front of a representation of Maria Lactans and to offer waxy replicas of one's own breasts as an offering.

The motif of Maria lactans also plays an important role in the iconography of the Last Judgment ( Last Judgment ). In the so-called intercession picture (picture of the intercession) the Madonna shows her free breast to the judging son to remind him that she once breastfed him in order to placate him as intercessor for the believers at the Last Judgment. This is preceded by the theological conception of a punishing God (Acts 10:42). If Bernhart-Königstein's interpretation is correct, then there is a modification of the motif from the rear in the center of Raphael's Transfiguration (“ Verklerung Christi ”, 1517 Rome, Pinacoteca Vaticana), which Bernhart-Königstein interpreted as the Last Judgment (Weltverklerung). Mary with her back freed, show her son, who has come down in the form of a red servant, the free breast in order to placate him for the group of sinners.

Interpretations

When integrating the pre-Christian Lactatio tradition into Christian religious culture, Christian theologians emphasize above all that Mary can be called theotokos / Theotokos because she gave birth to Jesus (dogmatically defined as true man and at the same time true God), but that she is not to be understood in the ancient Egyptian sense as Mother of God (Egyptian: mutnetscher ) because she is not the origin of the divine nature of Christ. Since Mary cannot be a goddess in the Christian sense, she cannot be the Mother of God in the sense of being the source of Christ's divinity. Therefore, early texts also emphasize that Mary only gave her child Jesus human milk. Ephraem the Syrian says in his Christmas Hymn IV (Beck 1959) that Mary, as a human mother, nourished her son with human milk, while at the same time everything that she gave him had its origin in the divinity of her son, who as God-Son mediator of creation and Is the origin of all things. So Ephraem got the idea that Mary breastfeeds her son on the human level, but that on the divine level she herself - like all other creatures - drinks of the divine milk of her son.

The resulting, now very strange acting transgender - imagery indicates that Jesus inherited as God the Son, the female wisdom personified (Schroer 1998). Metaphors that transcend gender boundaries are also not uncommon for ancient texts and can be found in the Old Testament (Isa. 60:16: milk of kings) as well as in the New Testament (1 Peter 2: 1-3: the pure milk of faith) is donated by Christ or by the Church as the body of Christ). And in the non-canonical psalms of Solomon , God the Father is milked by the Holy Spirit and gives holy milk that believers drink from a cup that is God the Son (Lattke 2009).

The later development deviates from this transgender imagery again and moves more and more to ascribing divine qualities to the milk of Mary. This is undeniably the case at the latest when milk relics are traded or Mary is claimed to be the nursing mother for adults, as in the Lactatio Bernardi. Mary no longer functions as earthly nourisher, but as heavenly mother, who, as a co-redeemer or at least mediator of salvation, gives the believers divine gifts through her milk. So it goes with Bernard of Clairvaux especially to eloquence and wisdom of the Milky beam which is why in some representations does not go to his mouth, but in his forehead. That Mary as a heavenly figure gives supernatural nourishment with her milk is also obvious where the milk brings relief from the torments in purgatory . The symbolic equation of healing water with the milk of Mary in the above-mentioned pilgrimage tradition also presupposes that the milk of the Mother of God has supernatural quality and effectiveness.

Overall, the history of interpretation shows an approximation of the ancient Egyptian conception of the divine milk. As before, Mary transmits divine essence or divine power to Isis or Hathor with her milk. The fact that Mary is not allowed to be a goddess in Christian dogmatics plays no role in religious theory in view of the functional similarities. In addition, the Christian concept of God is on a different level than the polytheistic . So Egyptian deities are not eternal, not omnipotent, not omnipresent and not omniscient. In this respect, a systematic of religious studies can definitely compare Mary with goddesses like Isis and Hathor.

- Examples

Jan van Eyck : Lucca Madonna (around 1437/38)

Albrecht Dürer : Mary with Child (around 1500)

Else Berg : Compositie No. 2 , around 1920

literature

- Jan Assmann : Egypt. Theology and piety of an early high culture , Stuttgart 1984

- Edmund Beck : Des Saint Ephraem the Syrian Hymns De Nativitate (Epiphania) (CSCO 187 - Scriptores Syri 83), Louvain 1959

- Galactotrophousa . and Maria lactans . In: PW Hartmann: The great art dictionary. Hartmann, Sersheim 1997, ISBN 3-9500612-0-7 .

- Hellmut Brunner: The Birth of the God King. Studies on the transmission of an ancient Egyptian myth, 2nd edition, Wiesbaden 1986

- Paul Eich: The Maria lactans. A study of the development up to the 13th century and an attempt to interpret it from medieval piety , Frankfurt am Main 1953 DNB 480378673 (Dissertation University of Frankfurt, Philosophical Faculty, June 17, 1953, June 17, 1953, 169 pages).

- Franz Groiss, Birgit Streiter, Christian Vielhaber a . a .: Maria lactans: The breastfeeding woman in art and everyday life , Wiener Dom, Vienna 2010, ISBN 978-3-85351-215-9 .

- Sabrina Higgins, Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans-Iconography , Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 3-4, 2012, 71-90

- Othmar Keel : God female. A hidden page of the biblical God , 2nd edition, Gütersloh 2010.

- Joachim Kügler : Why should Adults want to be Sucklings again? Some remarks on the Cultural Semantics of Breast-feeding in Christian & Pre-Christian Tradition , in: L. Togarasei, J. Kügler (eds.) The Bible and Children in Africa (BiAS 17), Bamberg: UBP 2014, 103-125 .

- Joachim Kügler, wonderfully magnificent, high and powerful. Religious historical notes on the extra-Christian "enrichment" of the image of Mary, in: Bibel und Kirche 68 (2013) 208-213.

- Joachim Kügler, The Heavenly Milk of Our Lady. The roots of the Coptic image of Mary and its aftermath, in: Das Heilige Land 145 (2013) Heft 2, 20-25.

- Joachim Kügler, Divine Milk from a Human Mother? Pagan Religions as Part of the Cultural Background of a Christian Icon of Mother Mary , in: Mother Divine Milk from an Human Mother

- Pierre Laferriere, La Bible murale dans les sanctuaires coptes , Le Caire 2008.

- Michael Lattke, The Odes of Solomon. A commentary (Hermeneia), Minneapolis 2009.

- Katja Lembke , The Iseum Campense in Rome. Study of the Isis cult under Domitian (Archeology and History 3), Heidelberg 1994.

- WH Müller, The Breastfeeding Mother of God in Egypt , Uetersen / Holstein 1963

- Edouard Naville, The Temple of Deir el Bahari , Part IV, London 1901.

- Hugo Rahner, The Birth of God. The teaching of the church fathers about the birth of Christ in the heart of the believer, in: Zeitschrift für Katholische Theologie 59 (1935) 333-418.

- Klaus Schreiner, Maria: Virgin, Mother, Ruler , Munich 1994.

- Silvia Schroer, The Book of Wisdom. An example of Jewish intercultural theology , in: Schottroff, Luise / Wacker, Marie-Theres (eds.), Compendium Feminist Biblical Interpretation, Gütersloh 1998, 441-449.

Individual evidence

- ↑ The Kestner Museum in Hanover also has a fragmentary representation for Mentuhotep II, which shows the king sucking divine milk from the teats of the Hathor cow. Inv no. 1935.200.82. Illustration and description by Rosemarie Drenkhahn (ed.): Egyptian reliefs in the Kestner Museum Hannover (collection catalog 5), Hannover: Kestner Museum 2nd edition 1994, 62 f.

- ↑ Interestingly, this motif is later integrated into the self-image of the Christian emperor, in that Rudolf II. (HRR) . had Tintoretto create a corresponding painting. (see right)

- ^ Sabrina Higgins: Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans-Iconography. In: Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 3–4 (2012) 71-90 ( online )

- ^ Higgins 2012

- ↑ LaFerriere 2008

- ↑ In a picture in the Iglesia de la Merced in Cusco , Peru , the saint drinks from Mary's breast. The painting is by the painter Ignacio Chacón , who worked from 1745 to 1775. Lactatio (milk miracle) of the Virgin Mary

- ↑ La Madonna del Suffragio, 1508, Chieti, Municipio. See Keel 2010: 133 f. with Fig. 28.

- ↑ In 1832 the pastor in charge wrote that in the dry season, crystal clear water gushes out of Mary's chest, but in the rainy season it is almost pearl-colored, which the pilgrims use to wash their eyes . The supply line was laid later so that the water flows from a pipe below the Mother of God with the baby Jesus into the fountain. In: Franz Schobesberger, Günter Pichler: Parish and pilgrimage church of the Visitation of the Virgin Mary and the old pilgrimage district of Brunnenthal . Passau 2008, ISBN 978-3-89643-697-9 , p. 22.

- ↑ Wolfgang Beinert , Heinrich Petri (Ed.): Handbuch der Marienkunde. Vol. 2, Pustet, Regensburg 1997, ISBN 3-7917-1527-5 , p. 536.

- ^ Gregor Bernhart-Königstein: Raphael's Transfiguration - The most famous painting in the world . Michael Imhof Verlag, Petersberg 2007, ISBN 978-3-86568-085-3 .

Web links

- Maria-Lactans (Spanish)