Gharial

| Gharial | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Gharial ( Gavialis gangeticus ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the genus | ||||||||||||

| Gavialis | ||||||||||||

| Oppel , 1811 | ||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the species | ||||||||||||

| Gavialis gangeticus | ||||||||||||

| ( Gmelin , 1789) |

The Gavial , even Gharial or Echter Gavial ( Gavialis gangeticus ), is the only one still living (extant) members of the genus Gavialis within the crocodiles (Crocodylia). The today only in Nepal and northern India living populations are severely threatened ( critically endangered ) and therefore on the endangered Red List species of the World Conservation Union IUCN listed.

features

Gaviale can grow up to six meters long, but such large individuals are no longer known today. Characteristic for the species is their long, narrow snout , which becomes thicker with advancing age and shorter in relation to the body. In adult males, a bulbous thickening grows on the tip of the snout, called Ghara , after the Indian word for pot . The males snort out a hissing sound through the nostrils below, which is modified and intensified by this thickening. The resulting sound can be heard about a kilometer away on a quiet day. Because of these gharials , gavials are the only crocodiles that are visibly sexually dimorphic . A large number of narrow teeth are offset from one another in the upper and lower jaw and interlock when the mouth is closed. The coloring of the animals varies from a light olive green to a light brown, the back and the tail are marked with darker bands and spots. The legs are very narrow and rather weak, but equipped with large webbed feet, especially on the hind legs.

The main feature of the fossil and recent gavials of the genus Gavialis is the configuration of the bones in the anterior region of the skull . Unlike with the other crocodiles, the nasal bone (nasalia) is not in contact with the premaxillary . With the other fossil Gavial genera this feature does not occur with the exception of Hesperogavialis .

Distribution and habitat

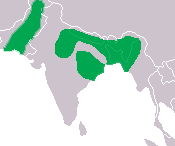

Once lived Gangesgaviale in all the major rivers of the northern Indian subcontinent , the Indus in Pakistan over the Plain of the Ganges up to the Irrawaddy in Myanmar . Today, however, they only occur in 2% of their previous range:

- In India there are small populations in the rivers of the protected areas of the National Chambal Sanctuary , Katarniaghat Sanctuary , Son River Sanctuary and in the monsoon forest - biome of Mahanadi in the Satkosia Gorge Sanctuary in Orissa , but where they do not appear to multiply;

- In Nepal there are small populations that slowly recover in the tributaries of the Ganges, such as the river systems of the Narayani-Rapti in Chitwan National Park and the Karnali- Babai in Bardia National Park .

They died out on the Indus, on the Brahmaputra in Bhutan and Bangladesh, and on the Irrawaddy in Myanmar.

The distribution area of the gharial overlaps with that of the marsh crocodile ( Crocodylus palustris ). In the Irrawaddy delta it overlapped with that of the saltwater crocodile ( Crocodylus porosus ). While marsh crocodiles are also found in stagnant waters such as oxbow lakes and ponds, gharials are apparently better adapted to the deep and fast-flowing rivers that spring from the Himalayas . For sunbathing, they prefer large sandbars with no vegetation and avoid grassy and rocky banks.

Way of life

Of all recent crocodiles, gharials are most strongly bound to water. Their legs are weak and hardly suitable for locomotion on land. On the other hand, they make rapid progress in the water thanks to their strong, high, laterally flattened oar tails and are extremely mobile in this environment. They just drag themselves out of the water to sunbathe on dry sandbanks , build nests for their clutch of eggs and lay eggs.

Gharials feed primarily on fish. Their snout (rostrum) is designed like a long fish trap . However, some adult individuals have been observed capturing wild ducks in the Narayani . Eggs are laid there in spring, from late March to mid-April. To do this, the females dig nests on the sandbanks, with several females sharing one sandbank. A female lays an average of 35 eggs.

Attacks on people have not yet been credibly described. Finds of human objects of daily use or jewelry in their stomachs are often used as evidence that they attack people or that they are eating the corpses given to the rivers for burial. However, they probably take up the objects secondarily together with other hard materials than stomach stones .

Systematics and fossil record

The gharial ( Gavialis gangeticus ) is the type taxon of the family Gavialidae and is traditionally the only surviving species of this family. The Sundagavial ( Tomistoma schlegelii ), which is native to Malaysia and western Indonesia , is traditionally not regarded as a close relative of the Gangesgavial, but rather to the real crocodiles (Crocodylidae) and therefore also referred to as the false gavial . The results of molecular genetic studies of the tribal history of the crocodiles suggest, however, that the Sundagavial is more closely related to the Gharial than to all other recent crocodiles and therefore also belongs to the Gavialiden.

The Gavialidae are one of the three recent families of the crocodiles (Crocodylia). Within the crocodiles, they were traditionally considered to be somewhat distantly related to real crocodiles (Crocodylidae) as well as to alligators and caimans (Alligatoridae). But here too, analyzes based on molecular data provide different results. Accordingly, the Gavialiden are more closely related to the Crocodyliden than to the Alligatoriden.

There are fossil finds of Gavialiden from the Miocene from North and South America , Africa and Asia . These include the species of the genus Rhamphosuchus from the Pliocene of India.

The following fossil species of the genus Gavialis are known: according to Vélez-Juarbe, Brochu & Santos, 2007; Brochu & Storrs, 2012 & Martin & Colleagues

- Genus: Gavialis

Oppel , 1811

- † Gavialis bengawanicus Dubois , 1908

- † Gavialis lewisi Lull , 1944

- † Gavialis browni Mook , 1932

- † Gavialis breviceps Pilgrim , 1912

- † Gavialis curvirostris Lydekker , 1886

- † Gavialis hysudricus Lydekker , 1886

- † Gavialis pachyrhynchus Lydekker , 1886

- † Gavialis leptodus Cautley & Falconer , 1836

threat

According to the IUCN, the gharial population has been falling dramatically since 1946. According to conservative estimates, the total population shrank by 96 to 98% over three generations in just 60 years - from probably 5,000 to 10,000 animals in the 1940s to fewer than 200. Of an estimated 436 animals in 1997, only 182 were left in 2006 Animals left, representing a population decline of 58% in just nine years.

There are many reasons for the drastic decline in the number of individuals. They were hunted for their skin, their body parts were processed into natural medicinal products and their clutches were looted because the eggs were considered a delicacy. Fishermen also chased after them and killed them because they viewed the large reptiles as competitors for food fish. Today, hunting is no longer seen as a major threat. On the other hand, the construction of dams , irrigation canals, the associated drainage and silting , but also the modification and straightening of rivers , artificial dikes and extensive agriculture, combined with livestock farming near rivers , led to an excessive and irreversible loss of their natural habitats . In the Chambal river basin alone, 276 irrigation projects have been documented up to the turn of the millennium. This threat continues to increase and goes hand in hand with the decline of other species resident in these biotopes , such as the ganges dolphin ( Platanista gangetica ), gangeshai ( Glyphis gangeticus ), marsh crocodile ( Crocodylus palustris ), hilsa ( Hilsa illisha ), the national fish of Bangladesh , and many others Types of fish and water birds .

protection

Since 2007, the species is classified as threatened with extinction in the endangered Red List species the IUCN listed and within the CITES Convention protected in the Annex. In India and Nepal, protection programs are under way aimed at the survival of the Gharial in its natural habitat. In the Indian National Chambal Sanctuary in Uttar Pradesh and in the Gharial Breeding Center in Nepal's Chitwan National Park , eggs are hatched and gavials are raised up to an average age of two to three years. When they have reached a length of about one meter, they are released into protected areas. But so far this program has not yet rebuilt viable populations anywhere.

Others

The photo of a 14-year-old Indian from a Gavial females with multiple pups on his head, titled Mother's little headful (Dt. About Mutters small headgear ) won the Young Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2013 (dt. Young Nature Photographer of the 2013 ) of the BBC - Wildlife Magazine .

literature

- Charles A. Ross (Ed.): Crocodiles and Alligators - Evolution, Biology and Distribution. Orbis Verlag, Niedernhausen 2002.

- L. Trutnau: Crocodiles: alligators, caimans, real crocodiles and gavials. Neue Brehm Bücherei Volume 593, Westarp Sciences, Magdeburg 1994.

- L. Trutnau, R. Sommerlad: Crocodiles. Biology and attitude. Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt am Main 2006.

- Joachim Brock: Crocodiles - A life with armored lizards. Natur und Tier Verlag, Münster 1998.

Web links

- Gavialis gangeticus in The Reptile Database

- Save Your Logo Initiative supports: Conservation of Gharial in Nepal

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Gavialis gangeticus in the Red List of Threatened Species of the IUCN 2013. Posted by: BC Choudhury, LAK Singh, RJ Rao, D. Basu, RK Sharma, SA Hussain, HV Andrews, N. Whitaker, R. Whitaker, J. Lenin, T. Maskey, A. Cadi, SMA Rashid, AA Choudhury, B. Dahal, U. Win Ko Ko, J. Thorbjarnarson, JP Ross, 2007. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ^ A b R. Whitaker, Members of the Gharial Multi-Task Force, Madras Crocodile Bank: The Gharial: Going Extinct Again. Iguana. Vol. 14, No. 1, 2007, pp. 24–33, PDF ( Memento from January 11, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ CA Brochu, AD Rincón: A gavialoid crocodylian from the lower Miocene of Venezuela. In: MR Sánchez-Villagra, JA Clack, DJ Batten (Ed.): Fossils of the Miocene Castillo Formation, Venezuela: contributions on neotropical palaeontology. Special Papers in Palaeontology. No. 71, 2004, pp. 61-79.

- ^ W. Langston, Z. Gasparini: Crocodilians, Gryposuchus , and the South American gavials. In: RF Kay, RH Madden, RL Cifelli, JJ and Flynn (Eds.): Vertebrate paleontology in the neotropics. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC 1997, pp. 113-154.

- ^ HR Bustard: Movement of wild Gharial, Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin) in the River Mahanadi, Orissa (India). In: British Journal of Herpetology. Vol. 6, 1983, pp. 287-291

- ^ TM Maskey, HF Percival: Status and Conservation of Gharial in Nepal. Presented at the 12th working meeting of the Crocodile Specialist Group , Thailand 1994.

- ↑ P. Priol: Gharial field study report. A report submitted to the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation , Kathmandu, Nepal, 2003

- ^ RJ Rao, BC Choudhury: Sympatric distribution of Gharial Gavialis gangeticus and Mugger Crocodylus palustris in India. In: Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. Vol. 89, 1990, pp. 313-314

- ↑ TM Maskey, HF Percival, CL Abercrombie: Gharial Habitat Use in Nepal. In: Journal of Herpetology. Vol. 29, No. 3, 1995, pp. 463-464

- ↑ J.-M. Ballouard, P. Priol, J. Oison, A. Ciliberti, A. Cadi: Does reintroduction stabilize the population of the critically endangered gharial (Gavialis gangeticus, Gavialidae) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal? In: Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. Vol. 20, 2010, pp. 756-761.

- ^ R. Whitaker, D. Basu: The gharial ( Gavialis gangeticus ): A review. In: Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. Vol. 79, 1983, pp. 531-548.

- ^ TM Maskey: Movement and survival of captive reared gharial Gavialis gangeticus in the Narayani River, Nepal. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of the University of Florida in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Gainesville, FL, 1989.

- ↑ Tomistoma schlegelii in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2013. Posted by: Crocodile Specialist Group, 2000. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- ↑ Ray E. Willis: Transthyretin Gene (TTR) Intron One Elucidates Crocodylian Relationships. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. Vol. 53, No. 3, 2009, pp. 1049-1054, PMC 2787865 (free full text)

- ↑ a b Jamie R. Oaks: A time-calibrated species tree of Crocodylia reveals a recent radiation of the true crocodiles. Evolution. Vol. 65, No. 11, 2011, pp. 3285-3297, doi : 10.1111 / j.1558-5646.2011.01373.x

- ↑ J. Velez-Juarbe, CA Brochu, H. Santos: A gharial from the Oligocene of Puerto Rico: transoceanic dispersal in the history of a non-marine reptile . In: Proceedings of the Royal Society B . Vol. 274, No. 1615, 2007, pp. 1245-1254. doi : 10.1098 / rspb.2006.0455 . PMID 17341454 . PMC 2176176 (free full text).

- ↑ CA Brochu, GW Storrs: A giant crocodile from the Plio-Pleistocene of Kenya, the phylogenetic relationships of Neogene African crocodylines, and the antiquity of Crocodylus in Africa . In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology . Vol. 32, No. 3, 2012, p. 587. doi : 10.1080 / 02724634.2012.652324 .

- ^ JE Martin, E. Buffetaut, W. Naksri, K. Lauprasert, J. Claude: Gavialis from the Pleistocene of Thailand and Its Relevance for Drainage Connections from India to Java . In: PLoS ONE . Vol. 7, No. 9, 2012, p. E44541. doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0044541 .

- ↑ "Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2013": The winners of the world's best nature photography competition. Photo gallery on Spiegel-Online, October 16, 2013, image 2 ( Memento from October 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive )