The great game

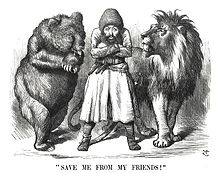

As The Great Game or The Great Game of the historic conflict between is Great Britain and Russia for supremacy in Central Asia called. It lasted from 1813 (after Napoleon's Grande Armée withdrew from Russia) until at least the October Revolution of 1917, but in fact until 1947 (the year the British withdrew from India).

term

The name The Great Game is usually attributed to the British secret service officer Arthur Conolly employed in Central Asia from 1835 to 1840 ; The expression found wider circulation through Rudyard Kipling's novel Kim (“ Now I shall go far and far into the North, playing the Great Game ”).

Today geostrategic conflicts between the United States , the Soviet Union or Russia , China and India are sometimes referred to as "The Great Game" or "The New Great Game", although it is not always about Central Asia, but also about other regions, such as for example the coastal countries of the Indian Ocean .

history

The Great Game revolved around supremacy in Central Asia . The Russians tried to advance to the Indian Ocean via Turkestan in order to be able to build an ice-free port. This was since Peter I. a primary goal of Russian foreign policy . As early as 1807, British agents reported that Napoleon and Tsar Alexander I had agreed to attack India together and wrest the subcontinent from the British Empire . Although this plan was never implemented, the British subsequently did everything possible to prevent the expansion of the Russian Empire in this area.

In 1837 the Russian officer Witkewitsch was on his way to the Afghan ruler Dost Mohammed . His company was part of the rapprochement between Afghanistan and Russia, which began in 1835. In Kabul he met the British officer and confidante of Dost Mohammed, Alexander Burnes . He was in Kabul on behalf of the British government to negotiate a contract. The core problem of these negotiations was the status of Peshawar . The British Governor General of Calcutta , Baron Auckland , called on Dost Mohammed to give up his claims on Peshawar and his rapprochement with Russia. As these demands were considered unacceptable, Burnes was expelled from Kabul. At the same time, the Russian ambassador, Count Simonitsch, had taken command of the Persian army. British troops then landed in the Persian Gulf . As a result, the Persian troops withdrew and both Simonitsch and Witkewitsch were ordered back to Russia. Ultimately, this situation led to the First Anglo-Afghan War .

General Chernyayev conquered Tashkent in 1864/65 and thus pushed Russia's expansion into the Trans-Caspian region and Central Asia under Tsar Alexander II . The later Kazakhstan was gradually incorporated into the Russian tsarist empire from the middle of the 18th century. As a result, the three Kazak-Kyrgyz hordes were formed there. In the 19th century Kazakh resistance to Russian rule increased: The Bökey horde , which wanted to restore the khanate , was founded in the area of the former Kazak khanate . However, what was later to become Kazakhstan was subjugated by General Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufmann (1818–1882) and subsequently subordinated to the General Government of Turkestan , in which all Russian acquisitions in Central Asia were combined. Kaufmann was at its head. Under him, the Kuldscha area (today Gulja or Yining, part of the Uyghur Autonomous Region Xinjiang ) was temporarily taken, which, however, had to be returned to China in 1881.

After that, Khujand , Jizzax and Samarkand (important junctions on the Silk Road ) also fell into Russian hands in quick succession . 1881–85 the Trans-Caspian region was annexed in a campaign led by Generals Mikhail Nikolajewitsch Annenkow and Mikhail Dmitrijewitsch Skobelew ; among others, Ashgabat and Merv (both in present-day Turkmenistan;. cf. Treaty of Akhal between the Russian Empire and Persia ) came under Russian control. Kushka (now located in Turkmenistan) represented the southernmost point of Russian expansion.

As a result of the Panjdeh incident , Russian expansion southward came to a standstill in 1887, when the Afghan northern border was established with the adversary Great Britain, which at the same time was established as the demarcation line of the spheres of interest and influence. Afghanistan thus became a buffer state between the two imperial powers, which was confirmed in the 1907 Treaty of Saint Petersburg . The Emirate of Bukhara and the Khiva Khanate remained formally independent, but were essentially protectorates along the chain of princely states in the north of British India (Khiva from 1873).

From the 1870s and 1880s, Turkestan played a relatively important economic role in the Russian Empire, also through cotton cultivation ; Due to the consequences of the American Civil War , the world market prices for the raw material had risen considerably. The Trans-Caspian Railway from Krasnovodsk (today Türkmenbasy ) via Samarkand to Tashkent and the Trans-Aral Railway from Orenburg to Tashkent were built. The Turkestan-Siberian Railway (Turksib) was still in planning when the First World War broke out and was only completed between 1927 and 1931.

Before the First World War , other priorities dominated the foreign policy of the adversaries: When Russia joined the Entente cordiale in 1907, this was expanded to form the Triple Entente , which was primarily directed against the global political ambitions of the German Empire (see Baghdad Railway ). German military and politicians planned to send troops to Central Asia during the First World War. In addition, Japan had become a new opponent of Russia on the Asian continent and in the Far East (cf. Russo-Japanese War ).

The last colonial acquisition of the Russian Empire was Tuva , which was occupied by Russian troops in 1911 and was formally a protectorate until it was officially incorporated into the Russian Empire on April 17, 1914.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Great Game shifted to Turkestan and Afghanistan, as well as to political conflict and friction in Turkey , Persia and British India .

Halford Mackinder's Heartland Theory

The Great Game also became the subject of geopolitics, an emerging field of research in the late 19th century . The British geographer Halford Mackinder formulated the Heartland theory as part of the British in his book The Geographical Pivot of History , which was presented to the Royal Geographical Society in London in January 1904 and published in the Geographical Journal in the same year imperial strategy. Their main thesis was that the domination of Eurasia as a pivot area (heartland) was the key to world domination . Great Britain, as the leading sea power, could not rule these vast areas due to its island location and had to reckon with the emergence of a dangerous competitor on the continent, also striving for expansion, above all with Russia. Mackinder stressed that both land and sea power had proven to be critical factors throughout history. The "Colombian Age" since 1492, in which sea power had played the decisive role, would in all probability be followed in the 20th century by an era in which land powers of the Eurasian continent would achieve dominance. Mackinder's paper was influenced by the Russian-Japanese conflict over control of Manchuria, which was already foreseeable at the time, in which the railroad would play a decisive role as a strategic military means of transport. A strong Eurasian land power like Russia or Germany or a combination of these powers could thus challenge the British supremacy in South Asia at any time. According to Gerard Toal , a leading exponent of the scientific discipline of critical geopolitics , Mackinder's ideas of 1904 and 1919 are an attempt by an elite to “discipline a world that is falling apart with its imperialist perspective”.

See also

literature

- Martin Ewans (Ed.): The Great Game: Britain and Russia in Central Asia . 8 volumes. Routledge Shorton, London 2004, ISBN 0-415-31638-3 .

- Peter Hopkirk : The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia . New edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford u. a. 2001, ISBN 0-7195-6447-6 (first edition 1990).

- Rudolf A. Mark : In the shadow of the “Great Game”: German “world politics” and Russian imperialism in Central Asia 1871–1914 . Ferdinand Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn 2012, ISBN 978-3-506-77579-5 .

- Karl E. Meyer, Shareen Blair Brysac: Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia . Counterpoint, Washington DC 1999, ISBN 1-58243-028-4 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Conrad J. Schetter: Small history of Afghanistan. The history of Afghanistan from ancient times to the present . 2nd updated edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-51076-2 , p. 55 ( available here ).

- ↑ Boris Shiryayev: Great powers on the way to a new confrontation ?. The "Great Game" on the Caspian Sea. An examination of the new conflict situation using the example of Kazakhstan . Kovac, Hamburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8300-3749-1 .

- ↑ Sören Scholvin: A New Great Game about Central Asia? (PDF) GIGA Focus 2, 2009; accessed on January 14, 2016.

- ^ Rani D. Mullen, Cody Poplin: The New Great Game. A Battle for Access and Influence in the Indo-Pacific . In: Foreign Affairs , September 29, 2015; accessed on January 14, 2016.

- Е↑ David X. Noack: The German Planning for Soviet and Chinese Turkestan 1914 to 1918: On the Way to British India , in: Первая мировая война - пролог XX века: Материалы материалы метериалы метериалы междунайка: Материалы междунай. Сергеев, Часть 1. М .: ИВИ РАН 2014, pp. 98-101.

- ^ Robin A. Butlin: The Pivot and Imperial Defense Policy . In: Brian Blouet (Ed.): Global Geostrategy: Mackinder and the Defense of the West. Frank Cass, 2005, pp. 36-54.

- ↑ Gearóid Ó Tuathail: Geopolitics - To the history of the origin of a discipline . In: Yves Lacoste et al .: Geopolitics - On the ideological critique of political spatial concepts . Promedia Verlag, Vienna 2001, pp. 9–28 (here: p. 16), quoted from: David X. Noack: Small overview of geopolitics . theheartlandblog.wordpress.com, October 19, 2013.