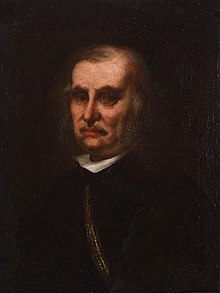

Juan Carreño de Miranda

Juan Carreño de Miranda (born March 25, 1614 in Avilés , Asturias , † October 3, 1685 in Madrid ) was a Spanish painter of the Spanish Siglo de Oro and the Baroque . He is considered one of the most important colleagues and successors of Diego Velázquez .

biography

Carreño de Miranda was the son of the eponymous Juan Carreño de Miranda and Catalina Fernández Bermúdez, who came from the district of Carreño in Asturias. According to Antonio Palomino , his parents were hidalgos and belonged to the ancient Asturian nobility. However, Pérez Sánchez believes that there is evidence that the mother was not Juan Carreño senior's wife, but only a domestic worker. The fact that he was just an illegitimate son would provide a plausible explanation for his later disinterest in an elevation to the nobility that Palomino mentions, for that would have meant thorough investigation and research into his family origins.

Around 1625 he moved to Madrid with his family. The financial situation was apparently difficult at first: his father was forced to ask King Philip IV for support several times . Despite his origins as a hidalgo, his father's activity as an art dealer can be proven.

Carreño de Miranda allegedly received his artistic training “against the will of his father” first from Pedro de las Cuevas and later from Bartolomé Román . According to Palomino, he finished his training with Román at the age of 20 and shortly afterwards gave a taste of his skills at the Colegio de doña María de Aragón . This work as well as frescoes for the Dominican convent 'del Rosario' in Madrid have been lost.

In 1639 he married María de Medina, daughter of a painter from Valladolid who was professionally connected to Andrés Carreño, an uncle of the painter. In 1649 Juan Carreño rented some houses with a view of the old Alcázar of Madrid, in front of the Church of San Gil.

In his art, Carreño de Miranda is not only influenced by Spanish painters such as Velázquez in particular, but also by the colorism of important non-Spanish painters, above all Titian , Rubens and Van Dyck . He painted both frescoes and pictures in oil on canvas. His first known and signed work is San Antonio of Padua preaching to the fish (today: Prado , originally: Oratorio del Caballero de Gracia), which is dated 1646. He achieved a privileged position among the painters active in Madrid and the surrounding area and received numerous important commissions from various religious orders , from the aristocracy and z. B. from the Cathedral of Toledo .

At the end of the 1650s, Juan Carreño de Miranda rose to some honorary posts: in 1657 he was elected alkali of the Hidalgos of Avilés, and in 1658 he was loyal ( fell ) to the city of Madrid for the nobility. In the same year, on the occasion of the elevation of Diego Velázquez to Knight of the Order of Santiago , Juan Carreño de Miranda belonged to Zurbarán , Alonso Cano and others. a. to the painters who previously gave testimony in his favor. Shortly afterwards, in 1659, Carreño was called together with Francisco Rizi de Guevara to work on the ceiling frescoes of the mirror room in the Alcázar in Madrid, under the Italians Agostino Mitelli and Angelo Michele Colonna . Velázquez was in charge of the entire decoration. These were scenes from the legend of Pandora , which, like many other works of art, were irretrievably lost in the fire of the Alcázar in 1734.

The decoration in the Hall of Mirrors began a phase of fruitful collaboration with Francisco Rizi, with whom he also worked on the oval dome of the Church of San Antonio de los Portugueses (1662–1666). The frescoes were later reworked by Luca Giordano but are the only surviving fruit of the collaboration with Rizi, along with some frescoes in the Camarín of the Virgen del Sagrario in the Cathedral of Toledo (1667). All other works by the two artists were later destroyed: the frescoes of the Hall of Mirrors and the Galería de las Damas in the old Alcázar, in the Camarín of the Virgen in the now lost church Nuestra Señora of Atocha (after 1664) and the dome frescoes of the octagon of the Cathedral of Toledo ( 1665–1671), which were replaced in 1778 by new frescoes by Mariano Salvador Maella due to their poor state of preservation . Carreño and Rizi also worked together in the Capuchin Church of Segovia and in the Chapel of San Isidro in the Church of San Andrés in Madrid (1663–1668). The latter were destroyed in the Spanish Civil War in 1936 when the church burned down.

Carreño de Miranda's masterpiece The Founding of the Trinitarian Order from 1666 ( Louvre , Paris) - a five-meter-high altarpiece that impresses with its “mastery of execution, subtle play of light and shadow, and imaginative scenery” - is according to research by Pérez Sanchez u. a. actually a fruit of the collaboration with Rizi.

Under Charles II of Spain, Juan Carreño de Miranda was officially appointed painter to the king in 1669 and court painter in 1671. From this point in time until his death he devoted himself mainly to painting portraits of the royal family and members of the court nobility. Several portraits of Charles II and his mother, the queen widow and regent Maria Anna are particularly well known . Also well known are his portraits of the Russian ambassador Pyotr Ivanovish Potemkin and Eugenia Martínez Vallejo, an unusually obese girl who was considered a “monster” and a “miracle” and whom he painted both dressed and naked. Carreño's portrait of Duque de Pastrana (1679, Prado, Madrid) is considered "one of the most important portraits in Spain of his time". His duties also included decorating and remodeling some of the halls of the El Escorial monastery-palace - where he finished work started by Velázquez - and restoring and copying some of the palace's paintings.

When they wanted to make him Knight of the Order of Santiago , as before Velázquez , he refused, saying: "Painting doesn't need honors, it can give it to the whole world".

Carreño de Miranda had numerous students, including Mateo Cerezo - who, according to Palomino, came closest to his style - Juan Martín Cabezalero , Francisco Ignacio Ruiz de la Iglesia and Pedro Ruiz González. The last three to work under his guidance in 1682 were Juan Serrano, Jerónimo Ezquerra, and Diego López el Mudo; they are mentioned in the will of María de Medina, widow of Carreño.

plant

Carreño's painting is characterized by "movement, richness of color and a loose brushwork", as can also be found in some other Spanish painters of his time, especially Francisco de Herrera the Elder. J. or his colleague and collaborator Francisco Rizi. Santiago Alcolea Blanch attests to him having a "dazzling sense of color". His artistic legacy includes several depictions of the penitent Magdalena in the desert (in the Museo de Bellas Artes de Asturias (1647) and in the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando), which Palomino described as " obras maravillosas " (miracles) , as well as several versions of the Immaculate Conception ( Immaculada Concepción ) and the Assumption of Mary , so popular in Spain , including a specially elaborated version from around 1657, which is now in the National Museum in Poznań ; plus a San Sebastián in the Prado, Madrid, and various portraits of other saints. Nowadays the already mentioned late portraits of the court of Charles II are particularly well known. The Prado has the largest collection of paintings by Carreño de Miranda with over 30 pictures.

- Sacred art (selection)

Madalena penitente (1654), Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando , Madrid

Assumption of Mary (1654), Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao

Martyrs of the Franciscan Order in Japan , Museo de Santa Cruz, Toledo

Maria lactans with San Bernardo , 1667 (private collection)

Maria immaculada ( Immaculate Conception , detail), around 1680, Iglesia parroquial de Nuestra Señora del Carmen, Marlofa ( La Joyosa, Saragossa )

- Portraits (selection)

The Duke of Pastrana (1649–1693), ca.1679, Prado , Madrid

Inés de Zúñiga, condesa de Monterrey (1660–1670), Museo Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid

Charles II as Grand Master of the Golden Fleece (around 1677), Rohrau Castle

Charles II approx. 1685, KHM , Vienna

Maria Anna of Austria (around 1670), Prado, Madrid

Lady from the House of Medinaceli (?), Ca.1683, Museo Fundación Lerma, Toledo

The Russian ambassador Pyotr Ivanovich Potemkin (1681–1682), Prado, Madrid

literature

- Juan Carreño de Miranda. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. ( online ; viewed August 9, 2018; English)

- Javier Portús Pérez: Carreño de Miranda, Juan. Biography on the Prado website , with a list of works in the Prado (as of August 9, 2018; Spanish)

- Cristina Agüero Carnerero (Ed.): Carreño de Miranda. Dibujos. Biblioteca Nacional de España-Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, Madrid 2017, ISBN 978-84-15245-70-4 . (Spanish)

- Ángel Aterido Fernández: El final del Siglo de Oro. La pintura en Madrid en el cambio dinástico 1685–1726. CSIC-Coll & Cortes, Madrid 2015, ISBN 978-84-00-09985-5 . (Spanish)

- Jonathan Brown: La Edad de Oro de la pintura en España. Nerea, Madrid 1990, ISBN 84-86763-48-7 . (Spanish)

- José Lopez-Rey: Velázquez - Complete Works. Wildenstein Institute / Benedikt-Taschen-Verlag, Cologne 1997.

- Rosa López Torrijos: La mitología en la pintura española del Siglo de Oro. Ediciones Cátedra, Madrid 1985, ISBN 84-376-0500-8 . (Spanish)

- Antonio Palomino: El museo pictórico y escala óptica III. El parnaso español pintoresco laureado. Aguilar SA de Ediciones, Madrid 1988, ISBN 84-03-88005-7 . (Spanish)

- Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez: Carreño, Rizi, Herrera y la pintura madrileña de su tiempo (1650-1700). Catalog of an exhibition at Palacio Villahermosa, Madrid, January - March 1986. Ministerio de Cultura, ISBN 84-505-2957-3 . (Spanish)

- Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez: Pintura barroca en España. 1600-1750. Ediciones Cátedra, Madrid 1992, ISBN 84-376-1123-7 . (Spanish)

Web links

- Painting by Juan Carreño de Miranda on: artnet (seen August 9, 2018)

- Articles on Catholic Encyclopedia (English)

- ARTEHISTORIA

- Juan Carreño de Miranda on: artcyclopedia

- Jusepe de Ribera, 1591–1652 , exhibition catalog from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (online as PDF), with material on Carreño de Miranda (see index)

- Velázquez , exhibition catalog from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (online as PDF), with material on de Miranda (see index)

Individual evidence

- ^ Antonio Palomino: El museo pictórico y escala óptica III. El parnaso español pintoresco laureado. Aguilar SA de Ediciones, Madrid 1988, p. 401.

- ^ Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez: Carreño, Rizi, Herrera y la pintura madrileña de su tiempo (1650-1700). Catalog of an exhibition at the Palacio Villahermosa, Madrid, January - March 1986, Ministerio de Cultura, p. 18.

- ↑ Antonio Palomino 1988, p. 407.

- ↑ The cumbersome procedure, e.g. B. Velázquez had to endure on the occasion of his elevation to Knight of the Order of Santiago , describes: José Lopez-Rey: Velázquez - all works. Wildenstein Institute / Benedikt-Taschen-Verlag, Cologne 1997, pp. 218–220. Juan Carreño de Miranda also appeared as a witness in the context.

- ^ Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez: Carreño, Rizi, Herrera y la pintura madrileña de su tiempo (1650-1700). ... 1986, p. 18.

- ↑ Antonio Palomino 1988, p. 407.

- ^ Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez: Carreño, Rizi, Herrera y la pintura madrileña de su tiempo (1650-1700). 1986, p. 30.

- ↑ Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez: Carreño, Rizi, Herrera y la pintura madrileña de su tiempo (1650-1700) 1986, pp. 19 & 198.

- ↑ Javier Portús Pérez: Carreño de Miranda, Juan. Biography on the Prado website

- ↑ Javier Portús Pérez: Carreño de Miranda, Juan. Biography on the Prado website

- ^ Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez: Pintura barroca en España. 1600-1750. Ediciones Cátedra, Madrid 1992, p. 289.

- ^ José Lopez-Rey: Velázquez - Complete Works. Wildenstein Institute / Benedikt-Taschen-Verlag, Cologne 1997, pp. 218–220.

- ^ José Lopez-Rey: Velázquez - Complete Works. Wildenstein Institute / Benedikt-Taschen-Verlag, Cologne 1997, p. 221.

- ^ Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez: Carreño, Rizi, Herrera y la pintura madrileña de su tiempo (1650-1700). 1986, p. 21.

- ^ Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez: Carreño, Rizi, Herrera y la pintura madrileña de su tiempo (1650-1700). 1986, 41-42.

- ↑ Juan Carreño de Miranda. Article in the Encyclopædia Britannica , (online)

- ^ Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez: Carreño, Rizi, Herrera y la pintura madrileña de su tiempo (1650-1700). 1986, 42.

- ↑ Cristina Agüero Carnerero (ed.): Carreño de Miranda. Dibujos. Biblioteca Nacional de España-Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, Madrid, 2017, p. 52, cat. 24.

- ↑ Juan Carreño de Miranda. Article in the Encyclopædia Britannica , (online)

- ↑ «… uno de los retratos más importantes de la España de su tiempo.» Javier Portús Pérez: Carreño de Miranda, Juan. Biography on the Prado website

- ↑ Here from the English: "Painting needs no honors, it can give them to the whole world."

- ↑ Santiago Alcolea Blanch: Prado. DuMont, Cologne 2002, p. 89.

- ↑ Santiago Alcolea Blanch: Prado. DuMont, Cologne 2002, p. 89.

- ↑ Antonio Palomino 1988, p. 402.

- ↑ Javier Portús Pérez: Carreño de Miranda, Juan. Biography on the Prado website

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Carreño de Miranda, Juan |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Spanish Baroque painter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 25, 1614 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Avilés , Spain |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 3, 1685 |

| Place of death | Madrid |