Kaufmann Kohler

Kaufmann Kohler (born May 10, 1843 in Fürth ; died January 28, 1926 in Cincinnati ) was a German-born American rabbi , pioneer of Reform Judaism and biblical scholar.

Life

Kaufmann Kohler, son of the clothes dealer Moritz (Moses) Kohler and Babette nee. Löwenmayer, on her mother's side, came from a traditional rabbi family. Grandfather Jacob Kaufmann took the surname Kohler in 1812. Kaufmann Kohler was named after his grandfather. He grew up in a traditional milieu; when he was five years old , his father taught him Chumash . Both his father's daily study of the Talmud and his mother's familiarity with the works of Lessing and Schiller shaped him. The language was spoken in German, written with Hebrew letters. At the age of six, Kohler received Talmud Torah lessons at Simon Bamberger's school in Fürth, and at the age of ten he moved to Hassfurt, where he was taught for four years by the well-known Talmudist Eisle Michael Schüler. He followed his teacher to Höchberg and continued his studies in Mainz. There he had the opportunity to learn Latin and Greek in addition to his Jewish studies. At the age of 19 Kaufmann Kohler moved to Altona and studied at the yeshiva there , which Jakob Ettlinger directed.

“The man who had the greatest influence on my young life ... was none other than ... Samson Raphael Hirsch .... Even if he kept his distance from his students, never invited us into his house or showed any interest in our well-being or our progress, his strong personality worked like a charm on his listeners. ”Kaufmann Kohler spent two years as a student in Frankfurt am Main Hirschs, while he also attended grammar school there and graduated from high school. In his class there were two sons of Abraham Geiger , but Kohler avoided any contact with their famous father. "I also never entered the reform temples in Frankfurt or Mainz, because I had learned to see them as tiflah - the perversion of a house of prayer."

After his time in Frankfurt, Kohler began studying at university. He was matriculated at Munich University in 1864/65. There he learned Arabic, and Hirsch's entire exegetical system collapsed for Kohler because it was based on the assumption that Hebrew was the original language of mankind. The philosophical and historical lectures did the rest to unsettle Kohler. He traveled to Frankfurt and called on Hirsch, but only received the cryptic information that anyone traveling around the world would also have to cross the blazing heat - "So go on and you will return home safely." But Kohler did not have the feeling that his Studies ever brought him back to the starting point, rather it seemed to him that he had irrevocably left the paradise of his childhood behind. Kohler continued his university studies for two and a half years in Berlin and received his doctorate in 1867 at the University of Erlangen with a thesis on Jacob's blessing (Gen 49). In it he dates the text not to the time of the patriarchs, but to the time of the judges . The blessing was "placed in Jacob's mouth". By receiving the Pentateuch criticism, Kohler broke with the Jewish interpretation of the Torah at the time; but at the same time he placed himself in this tradition by using the midrash and the medieval Jewish commentaries for an understanding of the text.

Merchant Kohler did pass the rabbinical exam, but his historical-critical interpretation of the Bible had closed this career path to him in Germany. Abraham Geiger reviewed The Blessing of Jacob positively and suggested that Kohler study Oriental Studies. At the University of Leipzig he came into closer contact with Franz Delitzsch and Julius Fürst . Geiger suggested that he seek a professional future as a rabbi in America, and when the Detroit Jewish community turned to Geiger and asked him to propose a young rabbi for the vacancy, Geiger recommended him and put him in contact with David Einhorn and other American reform rabbis.

In 1869 Kohler emigrated to America and found his first job as a rabbi at the Beth El Temple in Detroit, and in 1871 at the Sinai Temple in Chicago, where he served for eight years. This community was very open to the reform. In 1874 Kohler introduced a Sunday service in addition to the Sabbath service. His first Sunday sermon had the programmatic title: “The new knowledge and the old faith.” At the request of the older members, the congregation events were in German, and although Kohler spoke English orally and in writing, he gained little contact with the younger congregation members only spoke english.

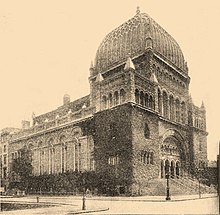

In 1879, Kaufmann Kohler succeeded his father-in-law David Einhorn as rabbi of the Beth-El community in New York. Under his direction, the number of members of the congregation grew, and in September 1891 a representative new synagogue was inaugurated ( Fifth Avenue and 76th Street).

From then on he had a leading position in American Reform Judaism. So he convened the rabbinical conference that passed the Pittsburgh Platform in 1885 , a document that formulated the principles of the reform movement. From 1903 until his retirement, Kohler served as President of the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. He was editor of the Jewish Encyclopedia and founder of the American Jewish Historical Society and the Jewish Publication Society .

A year after arriving in the United States, on August 28, 1870, Kohler merchant had married Johanna Einhorn. The couple had four children: Max J., Edgar J, Rose and Lili.

plant

Kohler's main work on Jewish theology was first published in 1910 in Leipzig in German: Outline of a systematic theology of Judaism on a historical basis .

Kohler dealt in several publications with the origin of Christianity in its Jewish context. He first noticed that Christian theologians approached the New Testament as the document of their faith much less critically than the Old Testament. Kohler's most important contribution to this topic was The Origins of the Synagogue and the Church, published posthumously only in 1929. In the article Christianity in its Relation to Judaism , which Kohler wrote for the Jewish Encyclopedia , he portrays Jesus of Nazareth as an impressive teacher and friend of the simple rural population of Galilee, but not as the Messiah . The gospels are already the result of a transformation of the original teaching of Jesus, for which Paul of Tarsus in particular was responsible. Kohler sees him as the actual founder of the Christian religion. “No wonder if he was frequently attacked and beaten by representatives of the synagogue: he used exactly this synagogue, which for centuries had propagated the pure monotheistic faith of Abraham and the law of Moses among the pagans, as a springboard for his anti- nomic and anti-Jewish agitation. “The First Jewish War led to an alienation between Jews and Christians, but both still expected the future messianic kingdom together. Only the Bar Kochba uprising then led to the separation and Romanization of the church: “Emperor Constantine completed what Paul had started - a world that was hostile to the faith in which Jesus had lived and died. The Council of Nicaea decided in 325 that church and synagogue had nothing in common, and whatever sounded like the unity of God or freedom of man, or reminded of Jewish worship, was removed from Catholic Christianity. ”Kohler then drew the further course of the Church history according to which led to the Trinitarian dogma, to the veneration of Mary and to the medieval adoration of images in Christendom, "so that the name of Jesus, the best and truest Jewish teacher, was avoided by the medieval Jew." Kohler then quoted Isaak Troki , one medieval Karaites , as a guarantor that the church could not keep any of its great promises. This shows Kohler's liberal position that an author of Jewish neo-orthodoxy would hardly have invoked a Karaite. More recently, according to Kohler, biblical criticism has succeeded in uncovering the image of the Jew Jesus and in returning to pure monotheism. Christianity is one of the ways to the future brotherhood of all human beings, but in this respect it is not superior to Islam and no substitute for Judaism, the mother religion of both. There are also other ways to a common goal, namely Brahmanism and Buddhism . By classifying Christianity among the world religions in this way, Kohler reversed the line of vision and analyzed Christianity in the way that Christian theologians evaluated Judaism, noted strengths and weaknesses and classified it historically.

Publications (in selection)

- The blessing of Jacob, with special consideration of the old versions and the Midrash, critically and historically examined and explained; a contribution to the history of Hebrew antiquity as well as to the history of exegesis . Julius Benzlau, Berlin 1867.

- Christianity in its Relation to Judaism . In: Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 4, pp. 49-59.

- Outline of a systematic theology of Judaism on a historical basis . Fock, Leipzig 1910.

- The Origins of the Synagogue and the Church. Macmillan, New York 1929.

literature

- Yaakov Ariel: Science of Judaism Comes to America. Kaufmann Kohler's Scholarly Projects and Jewish-Christian Relations . In: Görge K. Hasselhoff (ed.): The discovery of Christianity in the science of Judaism (= Studia Judaica. Research on the science of Judaism . Volume 54), Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2010, pp. 165–182 .

Web links

- Biographical portal of the rabbis: Kohler, Kaufmann, Dr.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Max J. Kohler: Biographical Sketch of Dr. K. Kohler . In: David Philipson (Ed.): Studies in Jewish literature: Issued in honor of Professor Kaufmann Kohler , Berlin 1913, pp. 1–10, here p. 1.

- ^ Kaufmann Kohler: Personal Reminiscences of my early life . Eggers, Cincinnati 1918, p. 3.

- ^ A b Kaufmann Kohler: Personal Reminiscences of my early life . Eggers, Cincinnati 1918, p. 8.

- ↑ Max J. Kohler: Biographical Sketch of Dr. K. Kohler . In: David Philipson (Ed.): Studies in Jewish literature: Issued in honor of Professor Kaufmann Kohler , Berlin 1913, pp. 1–10, here p. 4.

- ^ Kaufmann Kohler: Personal Reminiscences of my early life . Eggers, Cincinnati 1918, p. 9.

- ↑ Michael A. Meyer: Answer to Modernity: History of the Reform Movement in Judaism. Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2000, p. 388.

- ^ A b c Kaufmann Kohler: Personal Reminiscences of my early life . Eggers, Cincinnati 1918, p. 11.

- ↑ Max J. Kohler: Biographical Sketch of Dr. K. Kohler . In: David Philipson (Ed.): Studies in Jewish literature: Issued in honor of Professor Kaufmann Kohler , Berlin 1913, pp. 1–10, here p. 5.

- ↑ Max J. Kohler: Biographical Sketch of Dr. K. Kohler . In: David Philipson (Ed.): Studies in Jewish literature: Issued in honor of Professor Kaufmann Kohler , Berlin 1913, pp. 1–10, here p. 6.

- ↑ Max J. Kohler: Biographical Sketch of Dr. K. Kohler . In: David Philipson (Ed.): Studies in Jewish literature: Issued in honor of Professor Kaufmann Kohler , Berlin 1913, pp. 1–10, here p. 7.

- ↑ Max J. Kohler: Biographical Sketch of Dr. K. Kohler . In: David Philipson (Ed.): Studies in Jewish literature: Issued in honor of Professor Kaufmann Kohler , Berlin 1913, pp. 1–10, here pp. 7 f.

- ↑ Max J. Kohler: Biographical Sketch of Dr. K. Kohler . In: David Philipson (Ed.): Studies in Jewish literature: Issued in honor of Professor Kaufmann Kohler , Berlin 1913, pp. 1–10, here p. 10.

- ↑ a b Kaufmann Kohler: Christianity in its Relation to Judaism , p. 53.

- ^ Kaufmann Kohler: Christianity in its Relation to Judaism , p. 54.

- ↑ Yaakov Ariel: Wissenschaft des Judentums Comes to America , p. 171 f.

- ^ Kaufmann Kohler: Christianity in its Relation to Judaism , p. 58.

- ^ Yaakov Ariel: Wissenschaft des Judentums Comes to America , p. 173.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Kohler, merchant |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American reform rabbi |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 10, 1843 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Fuerth |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 28, 1926 |

| Place of death | Cincinnati |