Barthe Monastery

Kloster Barthe was the St. Nicholas consecrated monastery of Premonstratensians in Hesel in East Friesland . It was built between 1170 and 1184 as a nunnery and was the first branch of the order in East Frisia. In the centuries of its existence, the monastery acquired vast lands, most of which consisted of wasteland. These were then cultivated with great effort. After the Reformation, the convent gradually dissolved until the beginning of the 17th century.

Barthe was in contrast to the Cistercian - Kloster Ihlow a rather average East Frisian Convention , which is why it has been explored most extensively next Ihlow. In the years from 1988 to 1992 excavations took place at the Barthe monastery, which uncovered the floor plans of individual buildings.

history

From the foundation to the Reformation

A certificate of incorporation has not survived for Barthe. According to the current state of research, the monastery was founded by Premonstratensians between 1170 and 1184 as a subsidiary of the Premonstratensian double abbey in Dokkum . This makes Barthe the oldest branch of the order in East Friesland. It is possible that the attempt by the von Are family, closely associated with the Steinfeld Monastery (the mother monastery of Dokkum), to gain positions of power in the East Frisian-Gronian coastal area, contributed significantly to the establishment of an episcopal monastery. The name probably goes back to a settlement called Birgithi in the 10th century , the location of which has not yet been localized during the excavations.

The first residents probably came to East Frisia from areas east of the Ems. The Premonstratensians built Barthe on a Geest plateau on the eastern edge of a boggy lowland, which separated it from the settlement of Hesel, which had existed since the early 9th century. There was possibly land owned by the Werden monastery , which came to the Premonstratensians through the Bishop of Munster . Probably the better water supply and favorable wind conditions influenced the choice of the settlement area. The Premonstratensians rejected a location further to the east, where the terrain rose to a flood-proof height of up to 16 m.

From the beginning, the convent seems to have been a convent for women. Like the other monasteries in the order, it was run by a provost and a prioress . The few documents that have been preserved do not reveal anything about size, importance as a spiritual center, legal status in the state community or the work of the monastery in its environment.

In 1287, Barthe allegedly had 40 residents . The number of 140 conventuals given later by Ubbo Emmius is probably due to a reading error. In 1564, 24 sisters are listed by name. In total, the convention should have included around 50 people. Most of the inmates on the list came from the local area, so that Barthe is classified as an East Frisian farmer's monastery . The provost Johannes von Buiren seems to have been of outstanding importance to the residents around 1500, as he was appointed as a visitor to the Frisian circari .

secularization

In the course of the Reformation , the convent gradually died out. It is possible that Barthe was affected by the raid of Count Enno II in 1529, who in 1529 had all the Vasa sacra , i.e. silver and gilded chalices, godparents, monstrances, communion jugs and other valuable objects from all East Frisian monasteries handed over and then sold them. Sixty silver-gold-plated pieces of jewelry have been preserved from the Barther furnishings. They were part of the former church and garment decorations and were apparently hastily buried in the sacristy during the looting. The archive was also lost. It may have fallen victim to Ennos II's raid in 1529. It is also conceivable that it was destroyed in the fire of the church and part of the monastery buildings in 1558 or 1560 or that it was partially abducted to the Netherlands in 1563. In 1533 at the latest, Enno II acquired the property of the monastery and in the following years stationed a hunter in Barthe. In spite of this, the monastic community continued to exist, strengthened with novices from the still Catholic Netherlands and received a new provost. In 1563 the Counts of East Frisia appointed a nephew of this provost to manage the monastery property, which is now considered a domain, and thus transformed the convent into a secular women's monastery. This was connected to the neighboring parish of Hesel. Three nuns from the Groningerland therefore moved to the Maria Gratia zu Schildwolde monastery in neighboring Groningerland in 1563 at the request of the provost there . Other monastery inmates refused to take this step on the grounds that they could still pursue their Catholic faith in Barthe without hindrance. Possibly the provost wanted to counteract the sale of the possessions in the Groningerland by accepting the nuns and thus the legal claims to Barthe. In 1587 Schildwolde received the legal title to Barthes' possessions in Groningen.

Sisters of the order were last mentioned in Barthe in 1597. The pastor of the Hesel parish maintained church service in the local church until at least 1601. It is also known that two prebendaries lived from 1597 to 1602 , who from 1617 were housed in the poor house in Leer at the expense of the domain administration .

Further use

From 1604 the monastery property was leased separately from Oldehave for the first time and in the further course of the 17th century the property was divided between two leasehold farms including Oldehave. The tenants ran sheep and cultivated rye. They used the surrounding heathland to extract pests. This led to increased soil erosion in the exposed sandy soils. Agricultural areas were increasingly overrun by sand. The sand was mainly deposited to the east of the monastery grounds. The so-called Nunnenbarg, the nun's hill, was built on the site itself. Eventually the leasehold was given up and the remaining buildings were completely demolished around 1765. A new domain building was erected south of today's road from Hesel to Remels. This building was destroyed again by fire in 1774 and rebuilt as Bummert in the same year .

The site of the old monastery square was newly leased in 1771 with an area of 12 hectares. In 1859 this area was bought back by the state in order to demolish the building erected here and to integrate the area into the state forest that has now been created. The Barthe Monastery domain had meanwhile become an experimental farm and was finally closed in 1875. The former manor building became the forester's lodge for the local forester. The drifts could not be stopped until the 19th century through extensive reforestation. The Lantzius-Beninga family was largely responsible for this and made the former monastery properties in the area of today's Hesel municipality the starting point for systematic forest culture in East Frisia.

Archaeological rediscovery

There are no more building remains from the monastery today. Documents, contracts, image and written sources were largely lost in the course of secularization. In the 1990s, intensive archaeological excavations took place in the area of the former monastery, during which a ceramic fund of more than 45,000 pieces as well as economic facilities, ovens and water pipes were discovered. Several construction phases could be proven through the excavations. Wooden predecessor buildings were initially built for both the enclosure and the church. However, wall sections could not be determined by excavations. The floor plan could only be traced through foundation trenches. These were 2.3 m wide and 1 m deep. In order to give the buildings the necessary stability, they were filled with sand and then compacted.

There were few burials inside the church, including three brick-lined grave pits. The remains of nearly 360 human individuals have been recorded in the monastery’s former cemetery. 60% of those buried here were male, although evidence of a western gallery clearly identified the monastery as a women's monastery. Special areas in which, for example, only women were buried, could not be identified. According to the current state of research, all members of the monastery, including the staff, were buried on the site with equal rights. 7.5% of the deceased were less than 20 years old at the time of their death, 42% between 20 and 40 years and 41% between 40 and 60 years old. Only 9.5% of the examined individuals reached an age of more than 60 years. This resulted in an average life expectancy of 36.8 years for women buried here and 45.2 years for men. The main causes of death were infectious diseases resulting from malnutrition. The examinations of the corpses of women between 20 and 40 years of age often found otitis media, which could cause fatal meningitis.

Current condition

The area of the former monastery is now a state forest and, with around 600 hectares, one of the largest contiguous forest areas in East Frisia . The district forester's house named after the monastery is the largest in East Frisia. It includes the Heseler Wald , Oldehave in Firrel, Stikelkamp and the Ihlower Forst .

The deserted monastery is a little more than 2 hectares in size and predominantly with dense forest. In the north, east and south, overgrown sand walls surround the area. The so-called "Nunnenbarg" (nun's hill), which is about 10 meters high, protrudes from these in the northeast corner. On the west side of the former cloister courtyard, around half of the moat, around 10 meters wide and 4 meters deep, was preserved. In 2012, the municipality of Hesel had the floor plan of the former monastery buildings made visible with hedges. Boards provide information about the function of the building.

The results of the extensive excavations in and around Hesel are exhibited in the "Villa Popken" in Hesel. The focus is on the excavations at the former Barthe monastery. The secondary school in the joint municipality of Hesel also reminds of the Premonstratensian branch. It has been called the Barthe Monastery School since 1970 .

Economic activity

Barthe was one of the many economically insignificant women's convents in East Frisia. The basis of economic activity was the monastery property. These lands were in the area of the present-day communities Hesel , Firrel and Schwerinsdorf . The monastery had a farm in Oldehave, a few kilometers north, and another in Woltzeter Hammrich , which was sold to the chiefs of Loquard and Rysum as early as the 15th century . In 1508 the monastery acquired 250 hectares of land at Eelwerd near Opwierde in the province of Groningen , plus additional land in neighboring parishes.

The monastery was located in the center of a self-contained property that offered the comparatively most unfavorable economic conditions within East Frisia, as a large part of it consisted of moor and heather areas. This can probably be explained by the fact that the high medieval inland colonization of East Frisia was already approaching its climax when the first orders came to the region. In the development of the remaining wastelands, the monasteries led this colonization to its greatest and final development. The Barther property was divided into three core areas: the former monastery square, the farmyard in Oldehave to the north and the guests, some distance to the south. These areas are all covered with forest today. When the monastery was founded and during its existence, the soil was much wetter than it is today and was not suitable for agriculture. The historian Paul Weßels sees the land of the monastery as a marginal profitable location "whose use was last tackled and which is first given up again when the economy goes bad." Only in the immediate vicinity of the buildings was arable farming possible on a modest scale. The area was so small, however, that there was probably only space for small gardens and cattle housing. Somewhat better conditions existed at the Vorwerk in Oldehave. There were meadows, high-lying farmland and pastures in close proximity to one another.

Building history

Immediately after the founding of the monastery, the religious began to erect the most important buildings that were necessary for monastery life, i.e. the prayer room ( oratory ), kitchen and dining room ( refectory ) and a dormitory ( dormitory ) in barrack-like buildings made of wood. They had a roof made of straw or thatch.

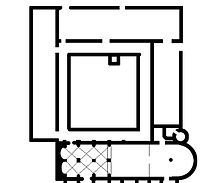

The first wooden church in the monastery was 21 × 7 m in size. Remains of a swelling beam construction from her were found on rows of supporting stones, which were anchored at points by posts. By radiocarbon dating of the remains of the fire preserved in the ground, their destruction by fire is dated between 1175 and 1280. This was followed by a new building made of wood. The construction of brick buildings in Barthe began around the middle of the 13th century. The raw materials required for this, such as clay, were extracted east of the monastery in the elevated Geest area, as indicated by deep traces of mining in the area. First the church was built. The single-nave church was an elongated late Romanesque brick building with a semicircular choir or apsidial closure . It had internal dimensions of 32.30 x 7.50 m. The church was equipped with a nuns gallery, which could be proven by three foundation pits. This installation, often richly decorated with paintings, is evidence that it was a women's monastery. This area of the church could be reached via a separate entrance and created space in the nave that lay people could use to attend church services without breaking the nuns' enclosure.

To the north of the church, the enclosure followed as a three-wing building. This is where the residential and farm buildings were located, which were rebuilt and expanded several times over the years. The results of the excavations up to 1350 reveal at least three main construction phases. The oldest part of the building is the north wing, construction of which began after the church was completed. After a fire, it was rebuilt in a modified form and only then connected to the north-west corner of the church by a west wing. The east wing has not yet been clearly identified. There, archaeologists excavated two parallel lines of buildings that could be used as a location. According to the results of the excavations, the eastern building was probably used for commercial purposes. This is indicated by the relics of a large oven and a storage container. The use of the western building is more difficult to determine. The remains of this building were destroyed by the construction of a modern cellar. A larger find of coins and jewelry ( treasure trove from the Barthe Monastery ) could be seen as the only remaining evidence of a building that already existed here.

In the last stage of expansion, the monastery grounds were 150 × 150 m in size. In the center of the enclosure, the cloister surrounded an inner courtyard measuring around 20 × 20 meters. On the north side there was probably a lavatory that was used by the monastery residents for liturgical cleansing. During the excavations, the archaeologists discovered a nine-meter-long water pipe made of stacked roof tiles, which was used to drain the lavatory and to remove the surface water from the inner courtyard.

After the Reformation, Barthe initially continued to exist as a monastery under the administration of the counts. At that time, two fires in 1558 and 1560 caused severe damage and destroyed large parts of the monastery. The church was rebuilt without a cloister and nunnery based on the model of a Protestant, generally accessible church and provided with a new entrance in the west. At the beginning of the 17th century the buildings were in poor condition. When repairing the Hesel church, stones from the former Barther monastery church were used. But it is said to have existed until 1680. Parts of other buildings - including a so-called residential building - were still preserved until 1767. They eventually had to be abandoned due to the drifting sand. In 1735 a stately hunting lodge was built on the southern edge of the forest.

Art historical features

The choir stalls

In the church of Nortmoor there are parts of a medieval choir stalls with carvings, which may come from the Barthe monastery. These are two seats with mythical animals on their cheeks and under the misericordia .

The treasure finds from the Barthe Monastery

In 1838, 752 sceattas (early medieval coin types) were discovered during earthworks. This is the largest early medieval coin find in Lower Saxony. You are in the East Frisian State Museum in Emden.

In the course of the excavations, archaeologists discovered a little sack tied with woolen thread under the floor of the sacristy. It contained more than 60 silver-gold-plated pieces of jewelry from the 14th century, which were probably part of the former garments and church decorations during monastic times. For the most part, these are decorative buttons and plates. In addition, there were two elaborately crafted fibulae and two ball pendants, each made of five gold-plated silver balls that were drawn on a wire. These are not interpreted as earrings, but as jewelry for a headdress and assigned to a workshop in Groß-Sander .

It is likely that the inmates of Barthe hurriedly buried the bag during the sack of the monastery in 1529.

literature

- Rolf Bärenfänger: From the history of the desert "Kloster Barthe", district of Leer, East Friesland. Results of the archaeological investigations from 1988 to 1992 . With contributions by A. Burkhardt, W. Löhnertz and P. Weßels. Problems of coastal research in the southern North Sea area 24 . 1997, pp. 9-252.

- Rolf Bärenfänger: Deserted Barthe Monastery near Hesel. Ostfriesland. Guide to Archaeological Monuments in Germany 35 . Stuttgart 1999, pp. 197-200.

- Angelika Burkhardt: Who lived and died in the East Frisian Barthe Monastery? Archeology in Lower Saxony 1 . 1998, pp. 94-96.

- Angelika Burkhardt: The cemetery of Barthe Abbey, Leer district, East Frisia. Problems of coastal research 27 . 2001 (2002), pp. 325-393.

- Hemmo Suur: History of the former monasteries in the province of East Friesland: An attempt . Hahn, Emden 1838, p. 101 ff. (Reprint of the edition from 1838, Verlag Martin Sendet, Niederwalluf 1971, ISBN 3-500-23690-1 ).

- Paul Weßels: Barthe - On the history of a monastery and the subsequent domain on the basis of written sources . Norden 1997, ISBN 3-928327-26-7 .

- Paul Weßels: Barthe . In: Josef Dolle with the collaboration of Dennis Kniehauer (Ed.): Lower Saxony Monastery Book. Directory of the monasteries, monasteries, comedians and beguinages in Lower Saxony and Bremen from the beginnings to 1810 . Part 1, Bielefeld 2012, ISBN 3-89534-957-7 , pp. 56–59.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Rolf Bärenfänger : The East Frisian monasteries from an archaeological point of view in: Karl-Ernst Behre / Hajo van Lengen : Ostfriesland. History and shape of a cultural landscape . Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 1995, ISBN 3-925365-85-0 , p. 249.

- ↑ Copy of a reconstruction drawing published here by Dr. Rolf bear catcher.

- ↑ a b Paul Weßels: Barthe - On the history of a monastery and the subsequent domain on the basis of written sources . Norden 1997, ISBN 3-928327-26-7 , p. 28.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Paul Weßels: Barthe . In: Josef Dolle with the collaboration of Dennis Kniehauer (Ed.): Lower Saxony Monastery Book. Directory of the monasteries, monasteries, comedians and beguinages in Lower Saxony and Bremen from the beginnings to 1810 . Part 1. Bielefeld 2012, ISBN 3-89534-957-7 , pp. 56–59.

- ↑ a b c Rolf Bärenfänger: Wüstung Kloster Barthe near Hesel , in: Rolf Bärenfänger (editing and processing): Guide to archaeological monuments in Germany , vol. 35: East Friesland . Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-8062-1415-8 , p. 197.

- ↑ a b Hemmo Suur: History of the former monasteries in the province of East Friesland . Hahn, Emden 1838, p. 101.

- ↑ a b Paul Weßels (local chronicle of the East Frisian landscape): Hesel, Samtgemeinde Hesel, district of Leer (PDF file; 89 kB), viewed on April 27, 2010.

- ↑ Paul Weßels: Barthe - On the history of a monastery and the subsequent domain on the basis of written sources . Norden 1997, ISBN 3-928327-26-7 , p. 13.

- ↑ Paul Wessels (working group of local chroniclers of the East Frisian landscape): Minutes of the meeting of the working group of chroniclers on December 6, 2002 at Gut Stikelkamp (PDF file; 48 kB), viewed on April 27, 2010.

- ^ Rolf Bärenfänger: The East Frisian monasteries from an archaeological point of view in: Karl-Ernst Behre, Hajo van Lengen: Ostfriesland. History and shape of a cultural landscape . Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 1995, ISBN 3-925365-85-0 , p. 241.

- ↑ Rolf Bärenfänger: Excavations in the desert of the Premonstratensian monastery Barthe, Ldkr. Leer, Ostfriesland ( Memento of the original from September 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed May 7, 2010.

- ↑ a b c Rolf Bärenfänger: Wüstung Kloster Barthe near Hesel , in: Rolf Bärenfänger (editing and processing): Guide to archaeological monuments in Germany . Vol. 35: Ostfriesland , Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-8062-1415-8 , p. 199.

- ↑ a b Rolf Bärenfänger: Wüstung Kloster Barthe near Hesel , in: Rolf Bärenfänger (editing and processing): Guide to archaeological monuments in Germany . Vol. 35: East Frisia . Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-8062-1415-8 , p. 198.

- ↑ a b Rolf Bärenfänger: Excavations in the desert of the Premonstratensian monastery Barthe, Ldkr. Leer, Ostfriesland ( Memento from January 13, 2005 in the Internet Archive ), viewed on April 27, 2010.

- ↑ Rolf Bärenfänger: Archaeological evidence of the working and living conditions in medieval East Friesland in: Hajo van Lengen (Hrsg.): The Frisian freedom of the Middle Ages - life and legend . Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 , p. 53.

- ^ Hemmo Suur: History of the former monasteries in the province of East Friesland . Hahn, Emden 1838, p. 102.

- ↑ a b Paul Weßels: Barthe - On the history of a monastery and the subsequent domain on the basis of written sources . Norden 1997, ISBN 3-928327-26-7 , p. 17.

- ↑ Hayo van Lengen: History and meaning of the Cistercian monastery Ihlow. Res Frisicae, treatises and lectures on the history of Ostfriesland 59 , 1978, pp. 86-101.

- ↑ Paul Weßels: Barthe - On the history of a monastery and the subsequent domain on the basis of written sources . Norden 1997, ISBN 3-928327-26-7 , p. 19.

- ↑ Paul Weßels: Barthe - On the history of a monastery and the subsequent domain on the basis of written sources . Norden 1997, ISBN 3-928327-26-7 , p. 21.

- ^ Rolf Bärenfänger: The East Frisian monasteries from an archaeological point of view in: Karl-Ernst Behre, Hajo van Lengen: Ostfriesland. History and shape of a cultural landscape . Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 1995, ISBN 3-925365-85-0 , p. 251.

- ^ A b Rolf Bärenfänger: The East Frisian monasteries from an archaeological point of view in: Karl-Ernst Behre, Hajo van Lengen: Ostfriesland. History and shape of a cultural landscape . Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 1995, ISBN 3-925365-85-0 , p. 243.

- ^ Heinrich Erchinger (local chronicle of the East Frisian landscape): Nortmoor, community Jümme, district Leer (PDF file; 32 kB), accessed on April 27, 2010.

- ↑ Robert Noah: The equipment of the churches in: Karl-Ernst Behre, Hajo van Lengen: Ostfriesland. History and shape of a cultural landscape . East Frisian Landscape, Aurich 1995, ISBN 3-925365-85-0 , p. 297.

- ↑ Rolf Bärenfänger: Archaeological evidence of the working and living conditions in medieval East Friesland in: Hajo van Lengen (Hrsg.): The Frisian freedom of the Middle Ages - life and legend . Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 , p. 51.

- ↑ Rolf Bärenfänger: Archaeological evidence of the working and living conditions in medieval East Friesland in: Hajo van Lengen (Hrsg.): The Frisian freedom of the Middle Ages - life and legend . Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 , p. 49.

Coordinates: 53 ° 18 ′ 31.9 ″ N , 7 ° 37 ′ 12 ″ E