Li prodigi della divina grazia nella conversione e morte di S. Guglielmo duca d'Aquitania

| Work data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | The conversion of Saint Wilhelm, Duke of Aquitaine |

| Original title: | Li prodigi della divina grazia nella conversione e morte di S. Guglielmo duca d'Aquitania |

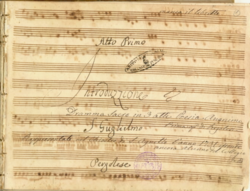

First page of the score from 1731 |

|

| Shape: | Dramma sacro in three acts |

| Original language: | Italian |

| Music: | Giovanni Battista Pergolesi |

| Libretto : | Ignazio Maria Mancini |

| Literary source: | Laurentius Surius |

| Premiere: | Summer 1731 |

| Place of premiere: | Courtyard of the Monastery of S. Agnello in Naples |

| Place and time of the action: | France and Italy, first half of the 12th century |

| people | |

|

|

Li prodigi della divina grazia nella conversione e morte di S. Guglielmo duca d'Aquitania or La conversione e morte di San Guglielmo or La conversione di S. Guglielmo d'Aquitania is a " Dramma sacro " (an operatic sacred stage work) in three Acts by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (music) with a libretto by Ignazio Maria Mancini. It was performed for the first time in the summer of 1731 in the courtyard of the monastery of S. Agnello in Naples and posthumously arranged as a two-part oratorio for a performance in Rome in 1742 .

action

The work is about the conversion of Saint William of Aquitaine . In the libretto published in Rome in 1742, the following preface is given:

«Sostenea Guglielmo duca d'Aquitania le parti di Anacleto antipapa contro il legittimo pontefice Innocenzo II; e scacciati avea dalle lor sedi i vescovi del suo dominio, seguaci del vero successor di San Pietro. Portatosi il grande abate di Chiaravalle San Bernardo negli stati di quel principe, non solamente lo ridusse all'ubbidienza del vicario di Cristo, e alla restituzione dei vescovi nelle lor sedi, ma ancora all'abbandono del mondo, e ad un'asprissima penitenza ( ex Surio, tomo I). "

“Wilhelm, the Duke of Aquitaine, claimed the territories of the antipope Anaclet II against the rightful Pope Innocent II and drove the bishops of his empire, who adhered to the true successor of St. Peter, from their possessions. When the great abbot Bernard of Clairvaux came to the states of this prince, he not only forced him to obey the vicar of Christ and to reinstate the bishops in their possessions, but also to give up the world and to perform extremely severe penance (according to Laurentius Surius , Volume I). "

first act

Duke Guglielmo banished the Bishop of Poitiers after he refused to renounce the rightful Pope. Thereupon San Bernardo (Saint Bernard of Clairvaux ), the most famous preacher of this time, went to the court of Wilhelm to persuade him to return to the bosom of the real Church. A devil and an angel as well as the captain Cuòsemo act as further figures. The devil first appears in the form of a messenger and later as a consultant under the name of Ridolfo. The angel appears as Page Albinio. These two try to influence the Duke's decisions in line with their own secret goals.

Despite Bernardo's admonitions, the Duke remains unimpressed (Arie Guglielmo: "Ch'io muti consiglio" and Arie Bernardo: "Dio s'offende"). He instructs Cuòsemo and Ridolfo (the devil) to force the rebellious bishop to be banished. The two are stopped by the angel who, to Cuòsemo's dismay, approaches his opponent with sharp words (the angel's aria: "Abbassa l'orgoglio"). The captain can only boast of his courage in a comical way (aria Cuòsemo: "Si vedisse ccà dinto a 'sto core"), while the devil is satisfied with the progress of his plans (aria of the devil: "A fondar le mie grandezze") .

Guglielmo, who has accepted the reason for the war against the Pope, asks Albinio (the angel) to entertain him with a song. The angel takes the opportunity to remind him of his duty as a Christian. His aria is about the admonition to a lamb to return to his flock (the angel's aria: "Dove mai raminga vai"). Guglielmo understands the symbolism, but explains that, like the Lamb, he loves freedom more than life.

But when Bernardo attacks him again with his sermon (Accompagnato and Arie Bernardo: “Così dunque si teme?” - “Come non pensi”), Guglielmo's determination wavers and he opens up to repentance. The act ends with a quartet in which, to the satisfaction of San Bernardo and the angel, and to the horror of the devil, the duke is converted (quartet: "Cieco che non vid'io").

Second act

In a mountainous and desert landscape, Guglielmo seeks advice from the hermit Arsenio. However, he first meets the devil in the form of the hermit. He tries to change Guglielmo's mind by appealing to his warrior pride (aria of the devil: “Se mai viene in campo armato”). Only the timely intervention of the angel in the form of a shepherd boy reveals the devil. The angel shows Guglielmo the way to the abode of the hermit (the angel's aria: "Fremi pur quanto vuoi").

Captain Cuòsemo, who followed his Lord on the path of penance and his pilgrimage, asks the false hermit for a piece of bread, but receives only ridicule and rejection (duet Cuòsemo / devil: "Chi fa bene"). The angel intervenes again, unmasks the devil and drives him away. Cuòsemo insults him (aria Cuòsemo: "Se n'era venuto lo tristo forfante") before he continues his journey.

Guglielmo finally reaches the real Padre Arsenio, who explains to him the advantages of the hermit life and asks him to leave worldly life behind (aria Arsenio: “Tra fronda e fronda”). The act closes with an emotional duet between the two men (“Di pace e di contento”).

Third act

After receiving the Pope's forgiveness, Guglielmo prepares to retreat to a monastery in a remote part of Italy. But a call from the past leads him to take part in a battle nearby. Cuòsemo, who has meanwhile entered a monastery founded by Guglielmo, complains about the privations of monastic life and is tempted again by the devil, who this time appears as a pure spirit and shows him the meager alternative between a return to the soldier's life and death by starvation who is sure to expect him in his new position (duet Guglielmo / Arsenio: “So 'mpazzuto, che m'è dato?”).

Guglielmo lost his sight in battle. He is overwhelmed by feelings of guilt and is desperate (Accompagnato and aria Guglielmo: “È dover che le luci” - “Manca la guida al piè”). The angel intervenes again and restores his eyesight so that he can gather companions and imitators. The devil returns as the ghost of Guglielmo's late father and urges him to regain the throne of Aquitaine and fulfill his duties to his subjects. Since Guglielmo remains adamant this time, he arouses the wrath of the monster who calls his devil brothers to whip him (aria of the devil: "A sfogar lo sdegno mio"). But the angel appears again and drives away the spirits of hell.

Alberto, a nobleman from the court of Aquitaine, arrives looking for news about Guglielmo and is intercepted by the devil, who, as in the first act, has assumed the form of the adviser Ridolfo. The devil hopes to win Alberto's support in his endeavor to induce the Duke to return to his former life. Cuòsemo opens the monastery gates and argues with the devil over his malicious remarks about monastery life. Finally he leads the two men to Guglielmo, whom they find surrounded by angels before old age, where he scourges himself in ecstasy (the angel's aria: "Lascia d'offendere"). The devil is horrified, but Alberto reveals his wish to enter the monastery himself. Cuòsemo provides a colorful description of the hunger and deprivations of monastery life (aria: "Veatisso! Siente di").

Exhausted from the privations, Guglielmo awaits death in the arms of Alberto. He resists a final temptation from the devil, who tries to arouse doubts about the ultimate forgiveness of his sins. But the Duke's faith can no longer be shaken after receiving the absolution of Rome and devoting himself to a life of penance. The angel greets Guglielmo's soul as it ascends to heaven. The devil, on the other hand, falls back into hell and vows to return with renewed anger in order to resume his work of damnation (duet: “Vola al ciel, anima bella”).

layout

The genus of the Dramma sacro

The dramma sacro (spiritual drama) was a fairly widespread genre of Neapolitan music at the beginning of the 18th century. It developed parallel to Opera buffa and to a certain extent to Opera seria ("Dramma per musica"). It differed from the contemporary oratorio , as defined by Alessandro Scarlatti , in the essential element of a scenic plot. Drammi sacri are therefore real dramatic works. They consist of three acts and deal with edifying episodes from the scriptures or the lives of the saints, but also contain comic elements that are represented (often in the Neapolitan dialect) by characters from the people. Comedy arises, for example, when a saint or angel explains questions about Christian doctrine and ethics to these people in detail. The roots of the dramma sacro lie partly in the genres of auto sacramental and comedia de santos , which were introduced in Naples during the period of Spanish domination (1559-1713). At the same time, it continued the old popular tradition of the Sacra rappresentazione - popular spiritual games in which comic characters who spoke dialect, frequent disguises and the obligatory conversion of the protagonists were already featured. Drammi sacri were not intended for the theater, but for places of worship such as monasteries, church squares or the courtyards of aristocratic palaces. They were mainly produced in the context of the conservatoires, whose students either took part in the composition or the performance in order to learn the then modern stage techniques. The highlights of this didactic tradition, which dates back to 1656, include Andrea Perrucci's Il vero lume tra le ombre, overo La spelonca arrichita per la nascita del Verbo Umanato (1698) and Francesco Durante's Li prodigi della Divina Misericordia verso li devoti del, which was performed annually for a long time glorioso Sant'Antonio da Padova (1705). Durante later taught at the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo and was one of Pergolesi's most important teachers.

libretto

The libretto was provided by the lawyer Mancini. But since it bears the name “poesia (di) anonimo” in the oldest surviving manuscript, Catalucci and Maestri consider Mancini's usually assumed authorship to be uncertain. It deals with the legendary story of Saint Wilhelm of Aquitaine and takes place at the time of the religious disputes between Pope Innocent II and the antipope Anaclet II. Lucia Fava pointed out in her review of the production in Jesi 2016 that the figure of San Guglielmo had elements shows the biographies of three different Wilhelms. In addition to William X, the Duke of Aquitaine and Count of Poitier, who was actually linked to the historical Bernard of Clairvaux , she names William of Gellone , also Duke of Aquitaine, who became a monk after a life devoted to the struggle against the Saracens, as well William of Malavalle , who made up for his dissolute life with heresy by making a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and retreating as a hermit. The blending of these three figures is the result of a hagiographic tradition and not the invention of Mancini.

music

Lucia Fava pointed out that the comic dimension of the work is not limited to the figure of Captain Cuòsemo. The continued disguises of the captain, the angel and the devil as well as some musical style elements of these figures and of San Bernardo are typical features of the opera buffa. Musically, the arias of the serious roles differ significantly from those of the comic. The former are virtuoso da capo arias of various characters (pathetic, proud, instructive or dramatic). Most of them are parlando style to add dynamism to the plot. The arias of the comic roles, on the other hand, are syllabic and full of repetitions, monosyllabic and onomatopoeic words.

Pergolesi's own manuscript of San Guglielmo has not survived. However, in Naples there is a score dated 1731. However, since this contains some pieces from Pergolesi's opera seria L'olimpiade, composed three years later for Rome, and other changes and has been shortened, researchers such as Helmut Hucke assume that it is a later arrangement. In L'olimpiade the following sentences of this score, see:

- The Sinfonia

- The angel's aria "Fremi pur quanto vuoi" in the second act, there the aria of Aristea "Tu di saper procura" (first act, scene 6)

- The duet San Guglielmo / Arsenio “Di pace e di contento” at the end of the second act, there the duet Megacle / Aristea “Ne 'giorni tuoi felici” (first act, scene 10).

Catalucci and Maestri also pointed out in the 1980s that the musical accentuation of the duet seemed to fit better with the text version of the olimpiade . Lucia Fava, on the other hand, suspected thirty years later that the acceptance of a self-loan might be closer to the truth. This duet was celebrated throughout the 18th century, and Rousseau chose it as an example for the "Duo" article in his 1767 Dictionnaire de musique.

The work contains seven characters, five of which - those of higher rank and with greater spiritual qualities - have high voices (soprano). The sources do not provide any information as to whether they were castrati or singers. The other two roles - the popular Cuòsemo, captain in the entourage of the Duke of Aquitaine, who hesitantly follows his master on the path to salvation, and the devil - are basses. The character Alberto, who probably corresponds to Wilhelm von Maleval's favorite historical student, only has a few bars of recitative in the third act (this role does not even appear in the list of performers for the performance in Jesi 2016). The characters of San Bernardo and Arsenio appear at different times in the play (in the first and second act, respectively). They were probably performed by the same singer, whose role pattern corresponded to that of the other singers: each actor was assigned three arias, or two for the title role and four for the more virtuoso role of the angel. In the score of the Biblioteca civica Giovanni Canna in Casale Monferrato , which minutely follows the libretto published in Rome in 1742, there is a third aria by Guglielmo, which would restore the balance in favor of the theoretically most important figure - but according to Catalucci and Maestri this can only be done difficult to fit into the dramatic plot of the Neapolitan manuscript ..

Instrumentation

The score marked with the year 1731 contains the following orchestra:

- two oboes

- two trumpets

- two horns

- Strings

- Basso continuo

Music numbers

Without taking into account Guglielmo's additional aria, the work contains a preceding sinfonia, fifteen arias, four duets, two accompaniment recitatives and secco recitatives. The following text starts in the score:

- Introduction

first act

- Aria (Guglielmo): "Ch'io muti consiglio"

- Aria (Bernardo): "Dio s'offende"

- Aria (angel): "Abbassa l'orgoglio"

- Aria (Cuòsemo): "Si vedisse ccà dinto a 'sto core"

- Aria (devil): "A fondar le mie grandezze"

- Aria (angel): "Dove mai raminga vai"

- Accompagnato and Aria (Bernardo): "Così dunque si teme?" - "Come non pensi"

- Quartet (Bernardo, Guglielmo, angel, devil): "Cieco che non vid'io"

Second act

- Aria (devil): "Se mai viene in campo armato"

- Aria (angel): "Fremi pur quanto vuoi"

- Duet (Cuòsemo, devil): "Chi fa bene"

- Aria (Cuòsemo): "Se n'era venuto lo tristo forfante"

- Aria (Arsenio): "Tra fronda e fronda"

- Duet (Guglielmo, Arsenio): "Di pace e di contento"

Third act

- Duet (Cuòsemo, devil): "So 'mpazzuto, che m'e dato?"

- Accompagnato and aria (Guglielmo): "È dover che le luci" - "Manca la guida al pie"

- Aria (devil): "A sfogar lo sdegno mio"

- Aria (angel): "Lascia d'offendere"

- Aria (Cuòsemo): “Veatisso! Siente di "

- Duet (angel, devil): "Vola al ciel, anima bella"

Work history

In 1731 Pergolesi's long years of study at the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo in Naples were drawing to a close. He had already started to make a name for himself and did not need to pay tuition fees, as he first appeared as a choir singer and later as a violinist at musical events. From 1729-30 he was first violinist ("capoparanza") of an instrumental group, and according to a later report it was the oratorio of Filippo Neri that made the most use of his artistic services and those of other "mastricelli" ("little masters") of the Conservatory made. After completing his studies, Pergolesi received his first commission from this religious order, and on March 19, 1731 , his first important work was carried out in the atrium of its church in Naples, today's Chiesa dei Girolamini and the then seat of the Congregazione di San Giuseppe, the oratorio La fenice sul rogo, o vero La morte di San Giuseppe, performed. The following summer, Pergolesi was to set the three-act dramma sacro by Ignatio Mancini Li prodigi della divina grazia nella conversione e morte di san Guglielmo duca d'Aquitania as the final thesis of his studies . It was performed in the courtyard of the monastery of S. Agnello in Naples, a seat of the Augustinian Canons of the Lateran . Leonardo Leo and Francesco Feo had received similar theses at the Conservatorio della Pietà dei Turchini twenty years earlier .

The libretto was provided by Ignazio Maria Mancini, an advocate and royal councilor of the Real Camera di Santa Chiara, who, according to Francesco Caffarelli, “indulged in poetic sins ” as a member of the Accademia dell'Arcadia under the pseudonym “Echione Cinerario ”. The audience consisted of the visitors of the Congregazione dei Filippini, d. H. from "half of Naples" ("mezza Napoli"), and the success was so great that the Prince Colonna di Stigliano, "Scudiere" of the Viceroy of Naples, and the Duke Carafa di Maddaloni - both also present - the "maestrino" promised their protection and the opening of the gates of the Teatro San Bartolomeo - at that time one of the most popular and important theaters in Naples, from which Pergolesi soon received the commission for his first opera seria La Salustia .

The autograph of San Guglielmo has not survived. Various traditional manuscripts, however, show a certain distribution, which the work surely enjoyed for a number of years - and that also outside of Naples: it was resumed in Rome in 1742, albeit in an arrangement as an oratorio in two parts without the comical elements of the original. The libretto was also published there.

There were staged performances on September 19, 1942 at the Teatro dei Rozzi in Siena in an arrangement by Riccardo Nielsen and on October 18 of the same year with the same performers, but apparently in a different production at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples. According to the program, most of the recitatives were replaced by spoken texts and an additional speaking role of the "predicatore" was entrusted with explanations of the content. The role of Padre Arsenio was merged with that of San Bernardo.

In 1986 Gabriele Catalucci and Fabio Maestri created a critical edition of the work on the basis of the oldest manuscript found in the Conservatorio San Pietro a Majella in Naples - the only one that also contains the comic elements of Captain Cuòsemo. The work was performed in concert under the direction of Maestri in Amelia and a live recording was published. Another performance took place three years later, in the summer of 1989, at the Festival della Valle d'Itria in Martina Franca under the direction of Marcello Panni and with the participation of two later stars of Italian bel canto, Michele Pertusi and Bruno Pratico .

In 2016 Pergolesi's drama was staged again at the Pergolesi Spontini Festival in Jesi . A critical reworking by Livio Aragona was played under the direction of Christophe Rousset and directed by Francesco Nappa.

Performances and recordings in recent times

- September 19, 1942 (staged performance at the Teatro dei Rozzi in Siena; arrangement by Riccardo Nielsen): Alceo Galliera (conductor), Virgilio Marchi (scene), Corrado Pavolini (direction and libretto adaptations), Rina Corsi (L'angelo), Giovanni Voyer (San Guglielmo), Aldo De Fenzi (San Bernardo), Raffaello Niccoli (il predicatore, speaking role), Mattia Sassanelli (Cuòsemo), Antonio Cassinelli (Demonio).

- October 18, 1942 (staged performance at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples): Alceo Galliera (conductor), Marcello Govoni and Friedrich Schramm (directors), Rina Corsi (L'angelo), Giovanni Voyer (San Guglielmo), Aldo De Fenzi (San Bernardo ), Raffaello Niccoli (il predicatore, speaking role), Mattia Sassanelli (Cuòsemo), Antonio Cassinelli (Demonio).

- December 18, 1986 (live recording of a concert performance in Amelia , Terni): Fabio Maestri (conductor), Orchestra da Camera Provincia di Terni. Kate Gamberucci (L'angelo), Bernadette Lucarini (San Guglielmo), Susanna Caldini (San Bernardo and Padre Arsenio), Maria Cristina Girolami (Alberto), Giorgio Gatti (Cuòsemo), Peter Herron (Demonio). Bongiovanni CD: 2060 / 61-2.

- Summer 1989 (concert performance at the Festival della Valle d'Itria in Martina Franca ): Marcello Panni (conductor), Orchestra RAI di Napoli. Gabriella Morigi (L'angelo), Maria Angeles Peters (San Guglielmo), Adelisa Tabiadon (San Bernardo), Bruno Praticò (Cuòsemo), Michele Pertusi (Demonio).

- June 14, 1997 (performance in the Church of San Marco in Jesi): Fabio Maestri (conductor), Stefano Piacenti (director). Cinzia Forte, Daniela Broganelli, Susanna Rigacci, Roberto Abbondanza, Roberto Ripesi.

- July 14th, 2011 (staged student performance in the monastery of San Rocco in Carpi): Mario Sollazzo (conductor), Paolo V. Montanari (director), instrumental ensemble of the “Vecchi-Tonelli” institute, singing classes from Tiziana Tramonti and Mario Sollazzo, Academy Dance Coreutica.

- September 9, 2016 (staged performance in Jesi): Christophe Rousset (conductor), Francesco Nappa (director), Benito Leonori (scene), Giusi Giustino (costumes), Les Talens Lyriques . Arianna Venditelli (L'angelo), Raffaella Milanesi (San Guglielmo), Sofia Soloviy (San Bernardo and Padre Arsenio), Clemente Antonio Daliotti (Cuòsemo), Maharram Huseynov (Demonio).

Work editions

- Contemporary libretto print: La conversione di San Guglielmo duca d'Aquitania. Zempel, Rome 1742. Full text in Varianti all'opera (Università degli studi di Milano, Padova e Siena)

- Text of a score from the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: San Guglielmo d'Aquitania. Full text of the second act at Varianti all'opera (Università degli studi di Milano, Padova e Siena)

- Text of a score from the British Library in London: La converzione di San Guglielmo. Full text at Varianti all'opera (Università degli studi di Milano, Padova e Siena)

- Text of a score from the Biblioteca civica Giovanni Canna in Casale Monferrato: La conversione di San Guglielmo duca d'Aquitania. Full text at Varianti all'opera (Università degli studi di Milano, Padova e Siena)

- Complete score from the Conservatorio San Pietro a Majella in Naples. Digitized at internetculturale.it

- Edition of the score: Guglielmo d'Aquitania / Dramma sacro in tre parti (1731). In: Opera Omnia di Giovanni Battista Pergolesi […]. Volume 3–4, Amici Musica da Camera, Rome 1939 ( online in the Google book search)

Web links

- Gli prodigi della divina grazia : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

Remarks

- ↑ According to another interpretation of the libretto, Guglielmo blinded himself as a kind of punishment. This reading was followed by the student performance of the work on July 14, 2011 in the monastery of San Rocco in Carpi.

- ↑ On this subject cf. the notes in the standard work Histoire des ordres monastiques, religieux et militaires by Pierre Helyot and Maximilien Bullot. They point out that since Wilhelm II “Werghaupt” there has been practically no Duke of Aquitaine who was not confused with Saint Wilhelm von Maleval (in fact the title “Werghaupt” refers to Wilhelm III. ) The work of the two French authors appeared only a few years after Pergolesi's Dramma sacro in Italian translation: Storia degli ordini monastici, religiosi e militari e delle congregazioni secolari […]. Volume VI. Salani, Lucca 1738, p. 150 ( online in the Google book search).

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Frederick Aquilina: Benigno Zerafa (1726-1804) and the Neapolitan Galant Style. Boydell, Woodbridge 2016, ISBN 978-1-78327-086-6 .

- ↑ a b c d Angelo Foletto: Quanta emozione nel dramma sacro ... In: La Repubblica of August 5, 1989, accessed on January 8, 2017.

- ^ A b c Carolyn Gianturco: Naples: a City of Entertainment. In: George J Buelow: The Late Baroque Era. From the 1680s to 1740. Macmillan, London 1993, ISBN 978-1-349-11303-3 , pp. 94-128 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ a b c d e Lucia Fava: Un raro Pergolesi on giornaledellamusica.it , accessed on January 8, 2017.

- ↑ Gustavo Rodolfo Ceriello: Comedias de Santos a Napoli, nel '600 (con documenti inediti) (= Bulletin Hispanique Volume 22, No. 2, 1920, pp. 77-100; online at Persée ).

- ↑ a b c d Gabriele Catalucci, Fabio Maestri: Booklet for the CD San Guglielmo Duca d'Aquitania. Bongiovanni, Bologna 1989, GB 2060 / 61-2.

- ↑ Helmut Hucke: Pergolesi: Problems of a catalog raisonné. In: Acta musicologica. Volume 52, No. 2 (July-December 1980), pp. 195-225, here p. 208.

- ↑ Fabrizio Dorsi, Giuseppe Rausa: Storia dell'opera italiana. Paravia Bruno Mondadori, Turin 2000, ISBN 978-88-424-9408-9 , p. 129.

- ^ Rodolfo Celletti: Storia dell'opera italiana. Garzanti, Milan 2000, ISBN 9788847900240 , p. 117.

- ↑ Raffaele Mellace: Olimpiade, L '. In: Piero Gelli, Filippo Poletti (eds.): Dizionario dell'opera 2008. Baldini Castoldi Dalai, Milan 2007, pp. 924–926, ISBN 978-88-6073-184-5 ( online at Opera Manager ( Memento from 5 March 2016 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ Duo. In: Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Dictionnaire de musique ( online ).

- ^ Helmut Hucke, Dale E. Monson: Pergolesi, Giovanni Battista. In: Grove Music Online (English; subscription required).

- ^ Claudio Toscani: Pergolesi, Giovanni Battista. In: Raffaele Romanelli (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 82: Pazzi-Pia. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2015.

- ^ Francesco Caffarelli: Foreword to the score edition by Guglielmo d'Aquitania / Dramma sacro in tre parti (1731). In: Opera Omnia di Giovanni Battista Pergolesi […]. Volume 3–4, Amici Musica da Camera, Rome 1939 ( online in the Google book search).

- ↑ a b Emporium: rivista mensile illustrata d'arte, letteratura, science e varieta. Volume 96, Edizione 574, 1942, p. 454 ( online at artivisive.sns.it ).

- ↑ a b Information on the performance in Siena 1942 at sbn.it , accessed on January 10, 2017.

- ↑ a b October 18, 1942: "Guglielmo d'Aquitania". In: L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia ..

- ^ Guglielmo d'Aquitania. Dramma sacro in tre atti di Ignazio Maria Mancini. Revisions e adattamento di Corrado Pavolini. Musica di GB Pergolesi. Elaborazione di Riccardo Nielsen. Since rappresentarsi in Siena al R. Teatro dei Rozzi durante la "Settimana Musicale" il 19 Settembre 1942-XX , Accademia Chigiana, Siena, 1942.

- ^ Catalogo dei libretti del Conservatorio Benedetto Marcello. Volume 68, Part 2. L. S. Olschki, 1994 ( snippet view on Google Books ).

- ^ Giovanni Battista Pergolesi. In: Andreas Ommer: Directory of all opera complete recordings. Zeno.org , volume 20.

- ↑ 1989–1990 - Alla Barbaresca , accessed January 9, 2017.

- ↑ Gianni Gualdoni: Storia della tradizione musicale teatrale a Jesi. Dall'età moderna ad oggi (= Quaderni del Consiglio Regionale delle Marche. Anno XIX, No. 144). April 2014, p. 303 ( Online, PDF ).

- ↑ Li prodigi della Divina Grazia nella morte e conversione di San Guglielmo, Duca d'Aquitania - Istituto Superiore di Studi Musicali O. Vecchi - A.Tonelli ( Memento from December 20, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) on comune.modena.it (Italian ), accessed January 9, 2017.

- ↑ Jesi: "Li prodigi della Divina Grazia nella conversione e morte di San Guglielmo duca d'Aquitania". Performance review on gbopera.it (Italian), accessed January 9, 2016.