Ludwig Wessel

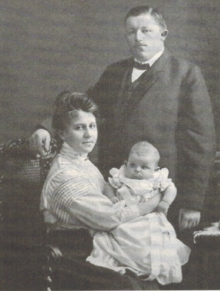

Wilhelm Ludwig Georg Wessel (born July 15, 1879 in Hessisch Oldendorf , † May 9, 1922 ) was a German Protestant pastor . He was the father of the SA storm leader Horst Wessel .

Life

Ludwig Wessel was born in 1879 in the Prussian town of Hessisch Oldendorf as the child of Georg Wessel, a train station host. After graduating from high school in Hameln , he studied theology with moderate success at the universities of Erlangen, Berlin and Bonn. During his vicariate , he was in 1904 at the University of Erlangen for doctor of philosophy doctorate. After his ordination - also in 1904 - he first worked for the Evangelical Church of the older provinces of Prussia ( ecclesiastical province of Westphalia) as an auxiliary preacher in Dortmund and Dorstfeld, then from 1906 to 1908 as a pastor in the Pauluskirche in Bielefeld . There his wife Margarete gave birth to their son Horst in October 1907, who was followed by their daughter Ingeborg in 1909 and their second son Werner in 1910 . The historian Daniel Siemens calls the relationship between the young Horst Wessel and his father "difficult".

In February 1908, Ludwig Wessel was appointed pastor of the Protestant parish in Mülheim an der Ruhr (Rhenish church province), where he worked until November 1913 and, in conflict with strictly Reformed and Pietist circles, redesigned the Petrikirche . Ludwig Wessel then worked at the Nikolaikirche in Berlin (ecclesiastical province of Mark Brandenburg). The Wessel family lived in the neighboring Jüdenstrasse . At the beginning of the First World War in 1914, he was the first volunteer chaplain of the German army to go into the field. In the first year of the war, he did his military service in Belgium as a government minister. This was followed by a transfer to Kovno , Lithuania , where the headquarters of Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg was located. In 1916 he met Hindenburg personally, of whom a hand-signed photo was on his desk until the end of his life.

He published some of his field sermons as books. These are shaped by national thinking and contain passages such as "Once again the days of August were jubilant with the ravishing sound of German ways of fighting who were happy to win". His war diary, From the Meuse to the Memel , published in 1918, is also teeming with such passages. During the war, his little anchored Christian-theological form took a back seat to his ethnic nationalism , especially during the initial enthusiasm for war and the victories on the Eastern Front . Nowhere in the traditional writings is there any criticism or even reflection on the millions of dead in the war. Wessel these seemed to be a "God-willed sacrifice in the struggle of the peoples". He saw the exploitation of the French and Belgian civilian population, including forced labor , as a necessary measure of order for these “work-shy and morally inferior people”.

Manfred Gailus called his worldview a “racially based, aggressive Pan-Germanism ”. In Ludwig Wessel's memory book, the second edition of which appeared in 1918, the war is only euphemistically presented. In it he writes of comfortable, meticulously clean hospitals with excellent food. An apt quote from his agitation, which has little to do with reality for the common soldier, is: "The very happy is a never-ending driving force, especially in the field."

Ludwig Wessel's violence was not just rhetorical. In May 1917 the court of the Kovno commandant's office sentenced him to a fine of 50 marks for deliberate minor assault. During a cure stay in Bad Nenndorf July 1916 Wessel had a fourteen-year-old who had previously annoyed his two younger children beaten, and was then against the boy's father, a Jewish horse trader who took him to task, with three slaps become violent. Thereupon the wife of the horse dealer reported Wessel for assault. There was no reaction from the church leadership to the verdict, but a few weeks later on August 31, 1917, Wessel resigned from the "military service relationship". He then preached to thousands of listeners on behalf of the War Press Office , for which the church leadership often granted him special leave.

At the end of the war, Ludwig Wessel returned to Berlin. After the November Revolution and the associated end of the previous system of the state church, the Weimar National Assembly reorganized the relationship between churches and state in the Weimar Imperial Constitution. The transitional government wanted to appoint Wessel on December 5, 1918 as the representative for evangelical affairs and as the successor to the provost of the Petrikirche , Gustav Kawerau , who had recently died . The new Minister of Education, Adolph Hoffmann , had previously asked von Wessel for a declaration of loyalty to the socialist government. The old Prussian Evangelical Upper Church Council immediately protested against the appointment, which was seen as an impermissible interference in internal church affairs. After Hoffmann quickly resigned as minister, Wessel soon renounced his appointment and worked again in the Nikolaikirche until his death in 1922. Gottfried Traub , who himself repeatedly attracted attention through differences with the church leadership, called Wessel's behavior during these days "unworthy" and, in retrospect, saw disciplining as the "correct answer".

According to his daughter Ingeborg Wessel, Ludwig Wessel rejected the new system of the Weimar Republic and remained a loyal supporter of the German Empire . Since Ingeborg Wessel and her mother fueled the cult of Horst Wessel with new information, also for economic reasons, during the National Socialist era, their statements were classified as only partially reliable in other questions.

In 1919, Wessel was briefly chairman of the Reich Citizens' Council .

Ludwig Wessel died in 1922 surprisingly from the effects of surgery and was on the St. Mary and St. Nicholas Cemetery I buried. His sons were buried in their father's grave in 1929 and 1930 respectively. On the 70th anniversary of Horst Wessel's death, the grave was desecrated in 2000, during which the skull of Horst Wessel was allegedly dug up and thrown into the Spree . It remained unclear whether the son's grave or that of his father Ludwig Wessel was actually desecrated. The perpetrators could not be identified. Because the grave was developing into a place of pilgrimage for neo-Nazis , the cemetery management had it leveled in June 2013.

literature

- Vaterstädtische Blätter (supplement to the general gazette for Mülheim / Ruhr and the surrounding area) v. November 6, 1932.

- Ernst Brinkmann: Ludwig Wessel in Westphalia . In: Yearbook for Westphalian Church History 78 (1985), pp. 125-134.

- Manfred Gailus: From chaplain of the First World War to the political preacher of the civil war. Continuities in the Berlin pastor family Wessel . In: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft , 50th year (2002), issue 9, pp. 773–803.

- Ernst Haiger: "A place of beautiful and noble art": The redesign of the Petrikirche 1912/13 . In: Architecture in Mülheim an der Ruhr. Journal of the Mülheim an der Ruhr history association 91/2016, pp. 115–189.

Web links

- The song that came from the rectory - article at zeit.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Manfred Gailus : The song that came from the rectory . Die Zeit , September 18, 2003. Retrieved May 17, 2010

- ↑ Horst Wessel: From the pastor's son to the SA thug. Article on focus.de , accessed on May 17, 2010

- ^ Ernst Haiger: "A place of beautiful and noble art": The redesign of the Petrikirche 1912/13 . In: Architecture in Mülheim an der Ruhr. Journal of the Mülheim an der Ruhr history association 91/2016, pp. 115–189.

- ^ A b c d Daniel Siemens: Horst Wessel. Death and Transfiguration of a National Socialist . Siedler, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-88680-926-4 , pp. 40-44.

- ↑ a b c d Sun-Ryol Kim: The prehistory of the separation of state and church in the Weimar Constitution of 1919. A study of the relationship between state and church in Prussia since the establishment of the empire in 1871.

- ^ Karl Kupisch : The German regional churches in the 19th and 20th centuries, accessed on May 17, 2010

- ^ Doris L. Bergen: Twisted cross: the German Christian movement in the Third Reich.

- ↑ From street thug to Nazi idol , accessed on May 17, 2010

- ↑ Heiko Luckey: Personified Ideology (= International Relations. Theory and History . Volume 5 ). V & R Unipress, Bonn University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-3-89971-503-3 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ The grave of SA man Wessel was completely leveled. In: berlin.de newsletter . August 8, 2013, accessed December 11, 2019 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wessel, Ludwig |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wessel, Wilhelm Ludwig Georg (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Protestant pastor and father of the SA storm leader Horst Wessel |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 15, 1879 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hessian Oldendorf |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 9, 1922 |