Luis Bagaría

Luis Bagaría , in Catalan Lluís Bagaria i Bou , (born August 29, 1882 in Barcelona , Spain , † June 26, 1940 in Havana , Cuba ) was the leading political cartoonist of the 1910s and 20s in Spain.

youth

Little is known about Bagaría's origins from the petty bourgeoisie in Barcelona. He was the only child of the shoe seller Luis Bagaría i Roca and his wife Emilia Bou i Mas. The family, however, must have enjoyed some prosperity because they owned a small house. From the beginning, Bagaría showed a disgust for all forms of violence and, like many Catalans , stood up for the republic . Politics struck him as dirty business - influences that must have come from his youth.

The fight against censorship and the Catholic Church already played a major role in the satirical magazines of that time. The drawings by leading Catalan cartoonist Josep Lluís Pellicer focused on the social issue and interpreted it in terms of a class struggle. With the loss of Cuba in 1898, the war was also often taken up in caricatures. Overall, the art form of caricature in Barcelona was far ahead of the capital Madrid in terms of the variety of its subjects, the sharpness of the political message and the quality of the drawings .

Bagaría's father died when Luis was 17 years old. He tried to support himself and his mother with odd jobs, in 1900 they both emigrated to Mexico, where Luis also only found work on a daily basis. In the end, when mother and son were looking for a way to return to Spain in Veracruz , they had to spend the night on park benches and in gate entrances. Luis Bagaría was deeply influenced by this experience of social decline. Upon his return, he became part of the Barcelona bohemians who met in the art pub Els Quatre Gats , and a close friend of Santiago Rusiñol .

Started as a cartoonist in Barcelona

Luis Bagaría never had a formal education - for example at an art academy. He practiced what was called caricatura personal in Spanish , much more often with the French foreign word portrait-charge : grotesquely distorted portraits in which a gigantic head sits on a ridiculously small body. Compared to the overloaded-looking portrait-charges of his competitors, Bagaría's first works already show that he mastered the division of space and the art of omission. His artistry quickly became known, so that his works were shown in first exhibitions in 1903 and 1905. In 1905 he started working for the daily La Tribuna in Barcelona. This was followed by further exhibitions and participation in various magazines, among which from 1908 De Tots Colors stood out, for which he regularly portrayed personalities from Barcelona's cultural life.

In the artist pubs frequented by Bagaría satirical magazines from all over Europe were on display. So it doesn't have to be a coincidence that his style can best be compared to that of the Briton Aubrey Beardsley , the illustrator of Wildes Salomé . In the Catalan context, Bagaría's caricatures can be assigned to Modernisme , the Catalan version of Art Nouveau . Bagaría still hesitated whether he should pursue a career as a painter and also painted landscapes on Mallorca .

In 1909 Bagaría undertook a trip to Cuba as part of an artist group led by Enric Borrás . He stayed in Havana longer than planned and worked for the Diario Español newspaper . It was here that a political topic first appeared in his work in cartoons attacking the alleged corruption of Governor Charles Magoon . After his return to Barcelona, he held several large solo exhibitions of his works in 1910 and 1911. Bagaría had become an integral part of Catalan cultural life; To be caricatured by him was considered an honor. Beyond the portrait charges customary at the time , in which the characters appear frozen, it goes beyond the fact that Bagaría succeeded in characterizing the caricatures with a typical movement.

Move to Madrid

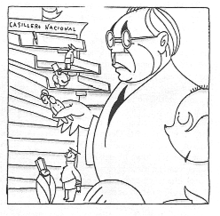

In February 1912, Bagaría - who was already married and had children - moved to Madrid. In the capital there was no noteworthy satirical magazine, the two leading caricaturists were "Apa" ( Feliu Elias ) and the Galician Alfonso R. Castelao . According to Bagaría, on the way from the train station he met Pedro Milá i Camps by chance , who invited him to work for his Madrid newspaper La Tribuna for a monthly salary of 250 pesetas. The La Tribuna, which was produced using rotary printing , was a start-up and was keen to experiment in its first phase. Bagaría mainly illustrated Tomás Borrás ' reports from cultural life. As a new element, he introduced a second, tiny figure in addition to the oversized characters, which sometimes even go beyond the scope of the drawing. The contrast additionally emphasizes the size of the portrayed personality, but it can also be understood as an indication of their vanity. The new style that Bagaría brought to Madrid caused a stir. He was quickly imitated, for example by Francisco López Rubio.

At that time newspapers often served the political aspirations of their owners; La Tribuna also supported Antonio Maura's line . Apart from the cultural section, Bagaría's cartoons appeared increasingly in the political section. His first big topic here was the Balkan Wars , which showed Bagaría's absolute pacifism . The cartoonist rejected any form of war, which distinguished him not only from right-wing representatives, but later also from many of his left-wing comrades. As a representative of a political fighting paper, he also attacked the head of government, the Count of Romanones , but Bagaría had increasing difficulties with the tendency of his newspaper and gave notice for the first time in August 1913. He spent a year illustrating an elaborate catalog.

First World War

In October 1914, shortly after the outbreak of World War I , Bagaría returned to La Tribuna . So it happened that he published some of his sarcastic caricatures with an absolute criticism of the war in this newspaper, even though it took the German-friendly side.

In 1915, Bagaría began to work with the newly founded magazine España by José Ortega y Gasset , for which he often designed the covers. Remarkably, Bagaría's pacifist caricatures and the essays by Ortega y Gasset - who in any case did not absolutely reject the war, even if he approved of Spain's neutrality in this conflict - found a place side by side in this magazine. With España , Bagaría enjoyed an artistic freedom that he had not known before.

The discussion about the war in Spain always had an internal political context. The German-friendly majority of politically interested Spaniards usually also supported the existing system and the monarchy. Those who were friendly to the Allies, like the Spanish left and many intellectuals, hoped for democratic conditions and an abolition of the monarchy. Bagaría became the caricaturist of the intellectuals. In the spring or summer of 1916, Bagaría was offered the astronomical sum of 5000 pesetas a month by the German embassy if he switched sides. John Walter, the organizer of British propaganda in Spain, paid him the comparatively meager sum of 12 pounds a month in return so that he could continue drawing according to his convictions. Bagaría received this British grant from October or November 1916 to early 1918.

In December 1917, the Basque entrepreneur Nicolás Maria de Urgoiti founded the daily El Sol , which became the mouthpiece of the liberal bourgeoisie. The intellectual figurehead was again Ortega y Gasset, Bagaría was represented from the beginning with his caricatures. The military became increasingly the target of his caricatures. There were the Juntas de defensa , which had been formed in the summer of 1917, the military suppression of a strike in 1919 in an electricity company in Barcelona, and the military undertakings in Morocco . However, Bagaría in El Sol had tighter ideological boundaries, he suffered from a certain internal censorship and was not allowed to publish anything about Morocco here.

A new feature in Bagaría's art of drawing was that he increasingly drew people as human-animal hybrids , for example when he characterized Unamuno as an owl or when he made a monkey for the simple Spaniard. In 1920 Bagaría joined the socialist party . His portrayal of the Spanish people, however, remained marked by astonishing arrogance. Bagaría fell back on the clichés that had been coined in French romanticism . The Spaniard appears to him as an Andalusian with the typical hat from Cordoba and nothing but a bullfight in his head. In the eyes of Bagaria, the ordinary Spaniard was lazy and unable to defend his own interests.

From the beginning, Bagaría was an opponent of imperialism , in the Spanish context of the intervention in Morocco. For example, in a caricature from 1913 he combined criticism of colonialism and bullfighting by placing a Muslim in a bullring. He shouts in horror: “Allah is great! What barbarism! ”With this, Bagaría questioned the usual justification of colonialism - a savage people must be civilized.

In Spain it was out of the question to caricature the king directly. Bagaría resorted to indirect means, for example when he showed a future visitor to a museum looking at a crown in a showcase. According to the accompanying text, this object had lost its function at the beginning of the 20th century. The lion often appears as a representative of Spain, which can be traced back in Spanish iconography to the early 1870s. In Bagaría, the lion is occasionally emaciated to a skeleton and droops its head.

Dictatorship and the fight against censorship

Like his employer El Sol , Bagaría initially watched the coup d'état of General Primo de Rivera in September 1923 with cautious hope. They saw the dictatorship - in agreement with large sections of public opinion - initially as an opportunity to get rid of the "old politics" (vieja política) . Bagaría recently denounced the corruption of the old system with a caricature in which politicians contaminated the beach simply because they went swimming. When Primo de Rivera did not want to relinquish power as promised, Bagaría's cartoons became more skeptical. The increasing distance was first expressed in a cartoon from January 1924 in El Sol , in which the dictator crouches as a perplexed toddler in front of his father's broken watch and does not know how to put it back together.

During the dictatorship, constitutional rights were abolished and censorship was tightened as a preliminary censorship. Bagaría had to resort to subtle means of criticism so that his caricatures could be approved by the censors. So he drew seemingly harmless nature scenes (dibujos para almohadón) and told his readers in the accompanying text that he thought they were painted blue and gold - the colors of the military. Bagaría even managed to publish a caricature of La Caoba , a prostitute who was patronized by Primo de Rivera to the point of perversion of the law, which the censor apparently missed. Bagaría's caricatures, on the other hand, were well understood by his public, and by 1925 he was famous for his persistent fight against censorship.

Caricatures about Morocco were considered particularly sensitive after the “ Annual Catastrophe ”. Primo de Rivera had originally promised to end the Spanish adventure in Morocco. Between September and December 1924 alone, when the Spanish military was involved in a delicate withdrawal operation, 27 caricatures were left with the censor. In May 1925 it was still possible for Bagaría to show his work at the exhibition of the Society of Iberian Artists (Sociedad de Artistas Ibéricos) . In the same year, however, the regime signaled that its campaign against censorship threatened the existence of El Sol . The editors of the newspaper continued to stand by their famous cartoonist, but in May 1926 there was an ultimatum that they believed they could not ignore and Bagaría left Spain for Buenos Aires in June . Bagaría was also known as a cartoonist in Argentina, and an exhibition of his drawings was opened by the President of the Republic as early as July. Bagaría lived, among other things, that he drew advertising for a hair tonic.

In November 1927, when the regime began to lose public support, Bagaría returned to Spain. He resumed work for El Sol on December 1st . In order not to immediately come into conflict with the censorship again, his newspaper initially commissioned him to portray personalities from cultural life, medicine, sports and the newspaper's editors. Gradually, Bagaría regained the terrain of political caricature. In 1929, for example, he criticized the hunger prevailing in Spain in several caricatures. In one example, a beggar suggests that Lent is the only time of year when as a citizen he can feel like everyone else.

Another group of caricatures demonstrate Bagaría's lack of understanding of certain developments. His portrayal of prohibition in the United States shows that for the Spaniard an alcohol ban was outside of the imaginable. And he also commented on the women's movement with typical Spanish machismo : he usually depicts couple relationships in such a way that a small male is suppressed by a dominant matron.

The second republic

In 1931 the government forced the owner of El Sol , Nicolás María de Urgoiti, to sell his shares, whereupon all important editors and employees left the paper. Many of them found shelter in a newly founded Urgoitis, Crisol , which later changed the title to Luz . At first, Crisol could only appear three times a week, and the initially poor production conditions also affected the quality of Bagaría's drawings. The monarchy came to an end for the time being . Bagaría, who had always advocated the republic as the ideal form of government, was at the height of his influence. In Josep Pla's judgment , the cartoonist had made a decisive contribution to the development of the republican movement.

Bagaría's role changed with the republic. If he had previously seen his task in unmasking the appearance of normality as hypocrisy, he was now concerned with defending the work of the republican government and conveying hope for a better future. He represented the republic as a little girl who first had to be spared. His caricatures only gained sharpness when he attacked the opposition, such as the anarchist union Confederación Nacional del Trabajo , which he accused of running the monarchists' business. He portrayed ultra-right Spaniards as old men with dark sunglasses. A popular target was also the militant Catholicism. He also refused to be played off as a Catalan against the Republic. His home is the street where he grew up in Barcelona.

During this time, his representation of the people changed. The lazy Spaniard, who wears the hat of Cordoba, loses his mustache, tightens his posture, wears the Jacobin cap and looks earnestly towards the tasks ahead. The cartoonist placed his art in the service of Manuel Azaña , whom he glorified as a teacher of the people. Bagaría had become a supporter of the state, his caricatures had lost their usual bite.

An artistic crisis

Bagaría's worldview has always been pessimistic. This was already evident at a lecture in Bilbao in 1922: “It is absurd to think that cartoonists are cheerful beings - on the contrary. The majority of humorists are sad people; true humor […] is the product of a great pain - the pain of being born […]. ”In 1933 Bagaría went through an artistic crisis that lasted almost a year. Hardly any caricatures of him have survived from this period. The constant alcohol abuse in the bohemian life, which he also cultivated as an established cartoonist, took its toll. Occasionally his depression increased to the point of death. At 51 years of age, he looked prematurely aged; close friends had died. He hardly reacted to the overthrow of the Azaña government.

The owner of Crisol / Luz , Urgoiti , who had always had Bagaría backing, went through a depression in 1932 that led to a suicide attempt. Finally, he gave a block of shares to the entrepreneur Luis Miquel. The editorial team of Luz then split and a group of 22 left-wing editors, including Bagaría, left the newspaper in 1933. A few days later, Bagaría returned, who must have realized that he had put his economic existence at risk. This created a paradoxical situation: Luz began to attack the socialists and Bagaría, who thanks to his fame now enjoyed absolute freedom, continued to support his party in the same newspaper.

In the spring of 1934, Bagaría developed a new form of artistic expression. He published a series of eighteen interviews under the title Diálogos espirituales y académicos , in which the text was combined with a photo of Bagaría as the interviewer and large-format caricatures. The interviewees were politicians from the current head of government Ricardo Samper and various ministers to the former dictator Primo de Rivera. As the title suggests, however, the conversations were often not about political, but rather philosophical and religious questions. Bagaría did not limit himself to the role of the questioner, but also made long statements about his own convictions. Interviews with political opponents such as José María Gil Robles were marked by violent confrontation from the start. On September 7, 1934, Luz ceased its publication.

Bagaría returned to his old newspaper, El Sol , which has now been turned several times, and which was celebrated as a great journalistic coup. In 1935, pre-censorship was reintroduced. During the uprising of Asturias and the Generalitat rebellion in Catalonia in 1936, the Lerroux government declared a state of emergency and suspended the entire press for ten days. Even after that, the preliminary censorship prevented any cartoon of Bagaría from being printed on these events. But the cartoons that still appeared show that Bagaría's work was rapidly deteriorating in quality. The content treated became increasingly abstract without him being able to find a suitable form for it. At a point in time, which must have been 1935 or 1936, Bagaría underwent alcohol withdrawal.

Propaganda in the civil war

During the Civil War , Bagaría's work was dominated by three themes: protesting against the "non-intervention" policies pursued by France and Britain; the mobilization to war; as well as appeals to the unity of all republican forces in the fight against fascism . The motif of Cain and Abel increasingly appeared - for example on the occasion of the assassination attempt on the socialist politician Indalecio Prieto ; Bagaría believed that the Spaniards were by nature cursed to fratricide. Unlike in 1931, he did not celebrate the popular front election victory in 1936. His disappointment is also evident in the portrayal of the formerly revered Manuel Azaña, whom he now accused of being driven by vanity. In July 1936, again cartoons from Bagaría fell victim to censorship.

The cartoons mostly appeared in the Catalan newspaper La Vanguardia . According to his biographer Emilio Marcos Villalón, the propaganda drawings from 1937 and 1938 are among Bagaría's weaker works. These include calls to fight, the glorification of José Miaja - the defender of Madrid - or thanks to Mexico, the only country that had openly supported the Spanish Republic from the beginning.

In the portrayal of Franco's two most important allies - Hitler and Mussolini - Bagaría, on the other hand, reverted to the old form. Mussolini had been caricatured by him for the first time in 1923, and since then he had frequently tried to ridicule the fascist leader. In 1935 Italy annexed Abyssinia . Bagaría desperately denounced the failure of the League of Nations on this issue. In this context, he succeeded in creating a caricature that is one of the two or three most reproduced drawings by him. While Italian planes bomb Abyssinian villages in the background, the residents flee. A child asks his mother: "Is it true that the world is full of Abyssinians?"

He caricatured Hitler for the first time in 1930. As a prominent feature, Bagaría drew his clenched mouth with a single, downwardly curved line and put a pimple on his head as a sign of German militarism. Hitler also appeared frequently as an object of his caricatures in the following years. On the occasion of the seizure of power, Bagaría showed how, in his opinion, German big business kept the Chancellor on a short leash. A caricature from 1937 in which a lonely Hitler walks on the roof of a skull had prophetic qualities.

Franco , on the other hand, came into Bagaría's sights astonishingly late, in 1937. The cartoonist denigrated the future Spanish dictator with big eyes, long eyebrows and a shy demeanor as completely feminine, described him as a traitor of the fatherland to German and Italian interests and as an agent of the Catholic Church.

Exile in France and Cuba

In the spring of 1938 Bagaría went into exile in France; in Spain his last cartoon was published in La Vanguardia on April 24th . He was accompanied by his wife Eulalia, he had to leave his old mother behind. One of his two sons, Jaime, had died on the Aragón front, the other, Luis, died soon after in Catalonia fighting for the Republic.

In Paris, Bagaría worked on Voz de Madrid despite his exhaustion and a heart condition . For this republican weekly newspaper he produced so-called aleluyas , which come close to a comic strip . In each of them Franco was defamed in a series of four pictures. In August Bagaría realized an exhibition in the gallery "Jeanne Castel", which was also shown in Lyon , and another exhibition a year later. At the end of May 1940 he left Europe with his wife and went to Cuba. He died there less than a month after his arrival.

Afterlife

Luis Bagaría was largely kept secret during Franquism . The caricatures of his last exhibition were bought by the Mexican diplomat Gilberto Bosques and are now in the National Library of Madrid . In 1983, Bagaría's rediscovery began with a major exhibition in the National Library. In 1988 Antonio Elorza published his first monograph.

literature

- Luis Bagaría: Caricaturas republicanas . Rey Lear, Madrid 2009, ISBN 978-84-92403-34-9 .

- Antonio Elorza: Luis Bagaría. The humor y la politics . Anthropos, Barcelona 1988.

- Emilio Marcos Villalón: Luis Bagaría. Entre el arte y la política . Biblioteca Nueva, Madrid 2004, ISBN 84-9742-380-1 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Original text: La teoría de Darwin - Mira, hijo: cuidate de leer estos libros. Darwin was a disgrace. ¿Pues no dice que el hombre desciende de nosotros?

- ↑ Original text: ¿Qué dices de los filósofos que opinan que la guerra regenera a los hombres?

- ↑ Original text: Los últimos serán los primeros. Jorge V. - Yo ser último en la guerra y primero en el reparto.

- ↑ Original text: En familia: - Hijos míos, creo que ha llegado el momento de que formemos nosotros una junta de defensa.

- ↑ Original text: Anido. - Dime, sinceramente, ¿mi política no era de pacificador?

- ^ La Tribuna , April 9, 1913.

- ↑ Original text: Preocupación diaria - ¿Se puede?

- ↑ Original text: Colaboración. El caricaturista - Señor censor: se conoce que su lápiz es mejor que el mío; por lo tanto, yo le suplico que me haga la caricatura. Si usted quiere, yo le daré la idea: puede dibujar un español rollizo y optimista que diga: "nunca había estado mejor que ahora".

- ↑ Original text: El Cristo moderno. El periodista - Para mi no hay cambios, sigo crucificado en las rayas del lápiz rojo de la censura.

- ^ El Sol , February 13, 1929.

- ↑ Original text: Calma (Dedicado a unos lectores que dicen que hago poco oposición al Gobierno) El dibujante. - Pensad que es muy niña. Si cuando crezca no va por buen camino, ya le enseñaremos el mal humor que gastamos los dibujantes.

- ↑ Josep Pla: Retrats de passaport . Obra Completa , Vol. 10. Destino, Barcelona 1992, p. 509. Quoted from: Marcos Villalón, p. 286.

- ↑ Original text: El canónigo Pildain

- ↑ Original text: Después del discurso de Santander. El español. - Pero D. Manuel, ¿que hace usted? Azaña. - Nada: un pueblo.

- ↑ ”Es un absurdo pensar que los caricaturistas son seres alegres; nada de eso. La mayoría de los humoristas son hombres tristes: el verdadero humorismo […] es producto de un largo dolor - dolor de haber nacido […]. ” quoted from Marcos Villalón, p. 189.

- ↑ Original text: Domingo de Ramos político - Ni una coma más y bastantes "puntos" menos.

- ↑ Original text: Geografía negra - Madre, ¿es vedad que el mundo está lleno de abisinios? . The Spanish original title contains the double meaning of "black" and "negro", which is considered a neutral term in Spanish. The speech defect vedad also gives the language a childlike appearance.

- ↑ Marcos Villalón, p. 400.

- ↑ Original text: Nuestra pesadilla ¡Y que siga la no intervención!

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bagaría, Luis |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Bagaria i Bou, Lluís (Catalan) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Spanish cartoonist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 29, 1882 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Barcelona , Spain |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 26, 1940 |

| Place of death | Havana , Cuba |