Carrot harrier

| Carrot harrier | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Black Harrier ( Circus maurus ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Circus maurus | ||||||||||||

| ( Temminck , 1828) |

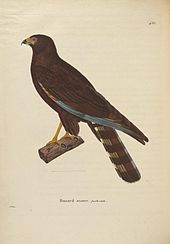

The black harrier ( Circus maurus ) is a bird of prey from the hawk family (Accipitridae). Characteristic of this medium-sized consecration is the uniform, black and white plumage pattern in males and females. The breeding areas of the Moor Harrier are limited to the southern two thirds of South Africa , Lesotho , the extreme south of Botswana and Namibia and a smaller exclave on the northern Namibian coast. It inhabits both dry, tree-poor fynbos highlands and extensive wetlands. The Mohrenweihe hunts mainly on small mice and quail , which it catches in the typical flight of wars . It usually breeds in a ground nest from August to December.

The Moor Harrier, first described by Coenraad Jacob Temminck in 1828, is close to a number of dryland species within the series and is probably the sister species of the South American gray harrier ( Circus cinereus ). BirdLife International classifies the population of 1000 to 1500 individuals as "endangered" ( vulnerable ). Above all, the decline in suitable habitats due to the intensification of agriculture contributes to the endangerment of the species.

features

Build and color

Compared to other species of the genus, the Mohrenweihe is relatively compact. The wings are relatively short, but the tail is rather long; Overall, it ranks in the middle of the range of consecration species. Regarding the size, there is a strongly pronounced reverse sex dimorphism in the Mohrenweihe , that is, females become larger and heavier than males. Females weigh 514–600 g and reach a wing length of 360–380 mm, a wingspan of 105–110 cm and a tail length of 235–268 mm. The total body length of female carrots is between 44 and 48 cm. Males are about 7% smaller and weigh 350–470 g; their wing length is between 331 and 347 mm. The tail length is 230-265 mm, where it is mostly in the lower end of this range. The tarsometatarsus is 63–73 mm long in both sexes.

The plumage of adult females and males is the same: the upper side of the body - head, back, upper arm cover - is black-brown; the basic color of the upper arm wings , hand wings and hand covers is a dirty gray. The hand covers show a black banding and a black edge stripe runs along the lower edge of the wing, which becomes wider towards the hand wings. The white rump contrasts strongly with the dark rest of the top; the tail is broadly banded black on a dirty gray background. The underside of the body with the throat, chest, stomach and forearm covers is also kept black-brown, only on the lower abdomen and the trousers there are bright feather hems from close up. The forearm and hand wings are colored white at the base. The arm wings show a thin banding, which becomes weaker towards the outside, at the lower edge of the arm wings another broad black band runs. The hand covers are broadly banded in black on a white background. The tips of the outer hand wings are colored dark gray and become darker and darker towards the outside, so that the outermost tips appear black. The control springs are broadly banded in black on a white background. Legs, wax skin and eye ring are yellowish-orange, the tip of the beak is black.

Juvenile carrots have plumage that differs significantly from this. The basic color of the head and top of the body is a dark brown, which is interwoven with light, sand-colored feather hems on the back and the upper wing coverts. The face veil is clearly visible in young animals because it is enclosed by the whitish throat, the light sand-colored neck and white stripes over the eyes. The upper arm wings are uniformly dark brown. The upper hand wings are colored gray-brown at the base and banded very indistinctly and thinly dark brown. The juvenile rump is white, the control feathers are broadly dark banded on the top on a gray-brown background. Over the sand-colored underside - blankets, stomach, chest and trousers - dense dark speckles run on the chest, and scattered dark speckles over flanks and under wing coverts. The underside of the flight feathers is banded dark on a gray background; only the base of the hand wings is white. The control feathers are banded in dark brown and white, with a dark terminal band at the end . The breast and head feathers are probably moulted first at the end of the first year of life, creating a transition form to the adult dress with a light belly, black breast and black head. Legs, wax skin and eye ring are darker yellow than in adult animals.

Flight image

Black harriers appear in the field as small to medium-sized birds of prey, which usually fly in jiggling gliding flight with wings angled at a height of one to two meters over dense vegetation. They appear more compact than most other consecrations, especially because of the relatively short and rounded wings. This makes the relatively long tail appear a little longer; overall the wingspan is about 2.2 times the total length. The wing beats are somewhat stronger and faster than in other consecrations.

Vocalizations

In their calls, the Mohrenweihe resembles other representatives of the genus. The alarm call consists of a fast, rattling chack chack chack chack . During the courtship flights, males make themselves audible with a high pwiiiieeep . The begging call of the brooding female, a gentle psju psju psju psju , is the most frequently heard utterance during the breeding season. Away from the nest, the species is usually acoustically inconspicuous and does not make any sounds.

Spreading and migrations

The breeding areas of the black harrier are mainly in South Africa and are concentrated south of the 17.5 ° C isotherm . They range from the Cape of Good Hope , where the main focus of the breeding population is, through Lesotho to around 26 ° S. The breeding areas also include the extreme south of Botswana and the south-western part of Namibia . A smaller exclave with a breeding population of five pairs is located on the Namibian north coast in the Uniab river delta . The limits of distribution in the north and northwest form the deserts and dry steppes of southern Africa. The black harrier is one of the few bird species that are endemic to the Cape flora area. With a size of around 1,060,000 km², the Mohrenweihe has the smallest distribution area of all mainland harriers.

Moor harriers are not typical resident birds , although many individuals, such as the northern Namibian population, remain in the breeding areas all year round. Many breeding birds from the Western Cape migrate in winter to eastern South Africa to the Free State and KwaZulu-Natal or north to the border region to Botswana and the southern two thirds of Namibia. There are higher temperatures in winter and a climate with less precipitation than in the Cape region. The extent of the migratory movements has not been researched, but in winter the sightings regularly accumulate in Botswana and Namibia, while the population density in the Cape region appears to be decreasing sharply. Parts of the populations also remain in the breeding areas in winter, where there is a closed snow cover during this time. The longest known distance a black harrier covered is 203 km from the southwestern Western Cape to Vanrhynsdorp .

habitat

Extensive landscapes, sparsely covered with low vegetation, form the habitat of the black harrier. Above all, low-precipitation plateaus and coastal areas with only a few trees, such as the fynbos and Renosterveld landscapes of the Cape region, are populated by it. The spectrum of habitat forms also includes semi-deserts such as the Karoo , dune vegetation, grasslands, wheat fields or other large-scale forms of agriculture. In contrast, the Moor Harrier is less common and especially in Namibia in wetlands, especially floodplains. Like the sympatric frog harrier ( C. ranivorus ) it is strongly tied to the occurrence of lamellar tooth rats ( Otomys ) and African welted grass mice ( Rhabdomys ). With the exception of Zimbabwe, the distribution area of Otomys irroratus is very similar to that of the black harrier. The vertical distribution of the species extends up to 3000 m, but is usually found below 2000 m.

Way of life

nutrition

The composition of the food of carrots obviously differs depending on the habitat. In coastal areas, small mammals dominate among the prey animals, while in the montane inland they are balanced with birds. Field observations in the South African Overberg district found 86% mammals, 6% birds and 8% reptiles among the prey animals on the coast. In the interior of the country, on the other hand, birds slightly outnumbered mammals with 52%, and no reptiles were found in the diet. However, these numbers only include those prey that could be identified from a distance, often only a rough classification or no classification at all was possible. Comparative data , for example from ridge analyzes , are not available. The mammals captured are probably mainly African welted grass mice ( Rhabdomys ) and lamellar tooth rats ( Otomys ), while the birds are usually quails ( Coturnix coturnix ). Other studies also found insects (grasshoppers, caterpillars, beetles), amphibians, nestlings, bird eggs and carrion among the diet of the black harrier. Birds are beaten up to a weight of 350 g.

Like all recent species of the genus, the black harrier usually hunts off the air. It flies with a few flaps of its wings, slightly bent wings and swaying body swings at a low altitude above the vegetation and directs its gaze to the ground below. This trickery flight is relatively energy-efficient because wind currents are also used and little force has to be used to flap wings. This enables the Mohrenweihe to cover long distances and to comb through large areas. She probably not only locates prey animals visually, but also acoustically, which is made easier by her face veil . Once it has identified a prey, it sets its wings upright, causing it to drop suddenly and rush towards the prey in order to grab it on the ground. The Moor Harrier rarely uses seat stalls or catches birds from flight. Hunting is not only done in the fynbos, in the Renosterveld and in wetlands, but also in agricultural areas such as pastures or cornfields.

Territorial behavior and settlement density

The settlement density of black harriers varies greatly, as a study from South Africa shows. While distances of only 100–290 m between individual nests lying close together were found in Koeberg , the distances at the edge of the Langebaan lagoon were at least 120 m and in Koue Bokkeveld at least 2 km. In the West Coast National Park the population density is about a couple per km². In individual cases, there can also be high densities with only about 50 m between three or four nests.

Reproduction and breeding

The breeding season for the black harrier begins around the end of July or beginning of August. During this time, the courtship flights typical of consecration can also be observed with this species. The male first rises in a circling manner and with exaggeratedly powerful wing beats to a great height above the potential nesting site on the ground. It then lapses into an up and down swinging flight, during which it utters loud calls at the top of every swinging movement. In addition, it performs barrel rolls and other acrobatic flight maneuvers. If the female joins in, the male sinks to lower heights and performs a number of other flight maneuvers there, but these are more spacious than the upward and downward swings shown above. Then it settles on the potential nesting site. Probably also the pair bond serves the bringing of food for the female, to which the prey pieces are given in the air. The male throws the prey vertically into the air, the female lies on its back in flight and uses the moment of inertia of the prey to grab it from the air. Mating takes place on the ground, in a few cases polygyny has been observed.

The nest is built by males and females in a division of labor. The male carries nesting material - grass, sedges or dry branches - which the female processes into a round or oval ground nest with a diameter of 35 to 45 cm and a depth of about 5 cm. Dry places that are well hidden by the surrounding vegetation are usually chosen as nesting sites. They are often found near watercourses or on the edge of wetlands; it is less common to breed in wet habitats. In the latter, the nest is usually built slightly higher.

The female lays 2–5 eggs - usually more in coastal areas than in the highlands (∅ 3.6 in coastal areas and 3.4 in highlands) - which are then incubated for 34 to 35 days. During this time, the male takes care of the female. It often covers distances of several kilometers, especially in the highlands, in order to get fodder. This becomes particularly critical as soon as the chicks hatch, as the need for food increases by leaps and bounds and the female only gradually begins to hunt herself again. In addition, there is a high risk of nest robbers in mountainous areas. The breeding success in the highlands is correspondingly lower than in coastal areas, where the food supply is better: in the latter it is 70%, in montane locations it is only 42%. The chick survival rate is 89% higher on the coast than in the highlands with 83%. The young birds leave the nest after 35–41 days.

Systematics

The Black Harrier was in 1828 by Coenraad Jacob Temminck in his with Guillaume Michel Jérôme Meiffren de Laugier, Baron von Chartrouse authored de Nouveau Recueil Planches Coloriées d'Oiseaux as " Falco maurus " first described . Temminck's first description was based on an individual who was sent from the Cape of Good Hope to the Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum . The specific epithet maurus means “black” in Latin and refers to the dark color of birds.

Within the orders ( Circus ) the Black Harrier belongs to a group of steppe and dry rural residents. The ornithologist Ebel Nieboer regarded them as an original representative of these so-called “steppe harriers”, which were the sister clade of the other species. An analysis of the cytochrome b gene of 14 species of consecration by Michael Wink and Robert Simmons came to the conclusion that the black harrier is a rather derived species in the steppe harrier complex and is compared to the South American gray harrier ( C. cinereus ) as a sister species. Wink and Simmons estimate the evolutionary age of the species to be around 2.8 million years. Their common sister clade is therefore formed by the steppe harrier ( C. macrourus ).

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Position of the Mohrenweihe within the genus Circus according to Wink & Simmons (2000) |

Existence and endangerment

The population of the Mohrenweihe is estimated at 1,000 to 1,500 individuals. However, the number of adult birds is likely to be less than 1,000 individuals. While it is believed that the species was extremely rare in the 1920s and 1930s and has increased its population since then, the population has declined slightly in recent decades. This is mainly due to the conversion of Fynbos and Renosterveld biotopes into agricultural areas, which do not offer the birds sufficient breeding habitat. This change took place mainly in the South African lowlands, so that the Moor Harrier is now moving to the coastal and mountain regions. However, especially in the latter, the breeding conditions are often suboptimal and the breeding success is comparatively low. Unlike the frog harrier ( C. ranivorus ), the moor harrier is hardly dependent on wetlands. However, due to global warming , it is expected that South Africa will tend to become more humid and that suitable breeding habitats will decline as a result. The population trend has been viewed as stable over the past few years, but BirdLife International continues to classify the black harrier as vulnerable ("endangered") due to its low population .

swell

literature

- BirdLife South Africa: The Atlas of Southern African Birds. Volume 1: Non-passerines. Avian Demography Unit, Johannesburg 1997. ISBN 0-620-20729-9 . ( Full text ; PDF; 213 kB)

- Leslie Brown, Emil K. Urban , Kenneth B. Newman: The Birds of Africa. Volume 1: Ostriches to Falcons Academic Press, 1988, ISBN 0-12-137301-0 .

- Odette Curtis, Andrew Jenkins, Robert Simmons: The Black Harrier. Work in progress . In: Africa - Birds & Birding 6 (5), 2001. pp. 30-39. ( Full text ; PDF; 689 kB)

- Odette Curtis, Robert Simmons, Andrew Jenkins: Black Harrier Circus maurus of the Fynbos biome, South Africa: A Threatened Specialist or an Adaptable Survivor? In: Bird Conservation International 14 (4), 2004. doi : 10.1017 / S0959270904000310 , pp. 233-245.

- James Ferguson-Lees , David A. Christie: Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001, ISBN 0-618-12762-3 .

- Julia Jenkins, Robert E. Simmons, Odette Curtis, Marion Atyeo, Domatillo Raimondo, Andrew R. Jenkins: The Value of the Black Harrier Circus maurus as a Predictor of Biodiversity in the Plant-rich Cape Floral Kingdom, South Africa. In: Bird Conservation International , 2012. doi : 10.1017 / S0959270911000323 , pp. 1-12.

- Ebel Nieboer: Geographical and Ecological Differentiation in the Genus Circus. University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1973.

- Austin Roberts (Ed.): Roberts birds of Southern Africa. Voelcker Bird Book Fund , Cape Town 2005. ISBN 0-620-34053-3 .

- Robert E. Simmons: Harriers of the World: Their Behavior and Ecology. Oxford University Press , 2000. ISBN 0-19-854964-4 .

- Coenraad Jacob Temminck, Meiffren Laugier de Chartrouse: Nouveau Recueil de Planches Coloriées d'Oiseaux: Pour Servir de Suite et de Complément aux Planches Enluminées de Buffon. Vol. 1. FG Levrault and Legras Imbert, Strasbourg and Amsterdam 1828. doi : 10.5962 / bhl.title.51468 . ( Full text )

Web links

- Circus maurus on www.globalraptors.org

- Circus maurus (Black harrier). Biodiversity Explorer, www.biodiversityexplorer.org.

- BirdLife International: Species Factsheet - Circus maurus

- Circus maurus inthe IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2009.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Circus maurus in the Internet Bird Collection

- Literature on the Moor Harrier in the Global Raptor Information Network

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Temminck & Laugier de Chartrouse 1828 , pp. 234-235.

- ↑ a b Roberts 2005 , p. 503.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Ferguson-Lees & Christie 2001 , p. 480.

- ↑ a b c d Roberts 2005 , p. 502.

- ↑ Brown et al. 1988 , p. 356.

- ↑ a b c Species factsheet: Circus maurus . BirdLife International , 2010.

- ↑ Jenkins et al. 2012 , p. 2.

- ↑ Curtis et al. 2004 , p. 233.

- ↑ Brown et al. 1988 , p. 357.

- ↑ a b BirdLife South Africa 1997 , p. 241.

- ↑ Ferguson-Lees & Christie 2001 , pp. 479-480.

- ↑ a b Curtis et al. 2004 , p. 238.

- ↑ Curtis et al. 2004 , p. 236.

- ^ Ferguson-Lees & Christie 2001

- ↑ Curtis et al. 2001 , p. 34.

- ↑ Simmons 2000 , p. 66.

- ↑ Curtis et al. 2004 , p. 239.

- ↑ a b Curtis et al. 2004 , p. 240.

- ↑ Nieboer 1973 , p. 73.

- ↑ Simmons 2000 , pp. 24-32.

- ↑ Simmons 2000 , p. 25.