Marsh harrier

| Marsh harrier | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Marsh harrier ( C. approximans gouldi ) ♂ |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Circus approximans | ||||||||||||

| Peale , 1848 |

The sump ordination ( Circus approximans ) is a bird of prey from the family of Accipitridae and the kind of the orders .

The brown and white marsh harrier is one of the largest representatives of its genus and feeds mainly on rodents , rabbits and birds, often also on carrion . The strongly disjoint distribution area includes parts of Australia , Tasmania , New Zealand and the islands of southern Oceania . With the exception of Australia and Tasmania, the marsh harrier is a resident bird . It inhabits wetlands such as marshes , swamps and river banks, but also pastures and cornfields.

Especially in New Zealand, where it is the largest bird of prey, the marsh harrier has developed from a classic representative of its genus to a primary user of carrion. Also because of her sturdy physique, which makes it difficult for her to fly in a flight that is otherwise typical for consecration , she often resembles buzzards more than other consecrations in terms of nutrition and hunting behavior .

In the mythology of the Māori, the marsh consecration is referred to as Kāhu , in the stories of the New Zealand native natives it plays the role of a messenger of the gods; they know the traditions of the Aborigines under the name Joongabilbil as the bringer of fire ( see below ).

features

Appearance and build

The marsh harrier is a very large and powerful consecration and, like other consecrations, shows a pronounced sexual dimorphism in terms of size and color.

The wing length of adult males of the nominate form C. approximans approximans is 392–415 mm, the tail length is 207–250 mm and the tarsus is 87–105 mm long. Males weigh 392 to 726 g. Females are on average up to 20% larger and 30% heavier. Their wing length is 418-430 mm, and their tail is slightly longer with 215-263 mm, while the tarsus is the same length as the male bird. Females weigh 622–1100 g. This makes the marsh harrier one of the heaviest and largest species of the genus.

Males of the nominate form are brown on top with light, reddish feather edges. The head and neck are slightly lighter than the back and are dashed. The wings of the hand as well as the control springs are washed out in gray and have thin, black bands. The underside of the hand and arm wings shows a similar, lighter color pattern, but with a white area at the base of the hand wings. The male's belly and chest are white or cream-colored; they have a reddish dash that becomes denser towards the throat and chest, but disappears towards the white rump. The females show a very similar plumage pattern. Overall, however, they are darker in color: the bands are clearly visible, and the top is more dark brown. The washed-out gray of the male is rather gray-brown in the female; in addition, the underside is very much denser and more continuous dashed.

The marsh harrier has a face veil typical for harriers , which stands out from the rest of the head and throat plumage by its dark brown color and a wreath of light feathers. The legs of adult birds are yellow, as are the wax skin and dark circles; however, some male birds also show an orange color on the legs.

Juvenile birds especially lack the light parts in the plumage of adult Marsh Harriers. Only the whitish-cream-colored areas at the base of the hand wings are already there, and white speckles or dashes form a light collar on the neck. The color of the underside of the body varies between dark and red-brown and already shows the basic structure of the dashed lines in colored animals. While the wax skin and legs of juvenile Marsh Harriers are yellow, they initially have brown circles under the eyes. In the male, these lighten up relatively quickly, so that they are yellow in the third year. In female animals, this process takes significantly longer and is sometimes only completed after the age of four. Juvenile marsh harriers show no differences in color, two-year-olds (immature) look very similar to females, which makes it difficult to determine the sex.

The down dress of the marsh harrier chicks is white to beige on the underside of the body; it is darker on the top. The dark brown feathers first appear on the shoulders, wings and tail. The beak and legs are already yellow. Freshly fledged birds often show reddish parts in the plumage, which are distributed as an irregular border on the control feathers and the hand and arm wings. Sometimes there are also remnants of the white down dress on the stomach.

Mauser

The first moult in the plumage of adult birds takes place in juvenile Marsh Harriers between April and September. From April to July only the body plumage is changed, then the birds shed the middle control feathers from August to November. The first postnuptial moult lasts five months in juvenile birds between November and the end of March (females) and one month later (males) from December to the end of April. The middle control springs are thrown off last; Males get the typical underwing markings through this moult.

In adult females, the postnuptial moult begins in December, at which time the young are about a week old. The moult lasts around six months until the end of May. Here, too, the moulting of the males takes place offset by a month because the male takes over the care of the females and young. In contrast to juvenile birds, the middle control feathers are thrown off first in adult marsh harriers. The hand wings are exchanged from the inside out.

Flight image

The marsh harrier is a medium-sized bird of prey, but for a consecration it is relatively large and strongly built. This can also be clearly seen in the flight image. While the wing load for most harriers is 0.2-0.3 g / cm², it is 0.39 g / cm² for male marsh harriers and even 0.41 g / cm² for females. This makes it more difficult for the marsh harrier to glide over the ground like other harriers in low flight. Instead, like buzzards , it often circles 20–100 m above the ground. Quiet, powerful wing beats, which are repeatedly interrupted by phases of gliding, are characteristic of the marsh harrier. The wings of the marsh harrier take the V-position typical for all birds of this genus. Sometimes it swings or leans to the side when gliding, and the marsh harrier often also lets its legs hang down in flight.

The deep, slightly tumbling flight, only a few meters above the ground, is mainly used where the marsh harrier mainly feeds on small mammals . In doing so, it uses the wind to cover long stretches over the open landscape and suddenly dive down when it sees the prey and grab it.

Vocalizations

Outside of the breeding season, the marsh harrier is acoustically rather inconspicuous bird. The vocalizations can be divided into different categories and differ depending on the situation: The male's courtship call consists of a short, plaintive kii-a , which is uttered in high flight. When inspecting the nest, a series of kii-o calls can be heard from the male . Before the food is handed over, the male calls the female with a soft chuck-chuck-chuck .

The female, in turn, calls out to the male with a deep siiiuh on various occasions , for example during courtship, when begging for food or when an intruder appears; the same applies to begging cubs.

When threatened by predators, marsh harriers emit a loud, sharp chit-chit-chit as a threatening cry. This is to be distinguished from the cry of fear, a loud cheeiit , which can be heard when the birds are startled by humans or when they are clawed by members of their own species.

distribution

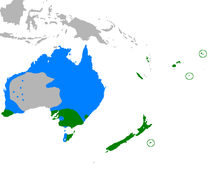

The range of the marsh harrier includes the southeast and the extreme southwest of Australia, Tasmania and the Loyalty Islands , New Caledonia , the Wallis Islands , Fiji , Vanuatu and the Chatham Islands . Marsh harrier was introduced on the Society Islands , as well as in Tahiti in 1880 , where it is believed to have caused the extinction of the Tahitian fruit pigeon ( Ducula Aurorae ). There are also isolated reports of more northerly broods, for example on the north coast of New South Wales or in northern Queensland .

The marsh harrier has probably only been at home in New Zealand since the early modern period and is missing from the finds from the early Holocene . Since the Quaternary , forests and species characterized by island gigantism such as the moas , the Haastadler ( Harpagornis moorei ) and the larger Eyles-Weihe ( Circus teauteensis ) have predominated there. This only changed with the arrival of the Maori in the 13th century. These hunted the moas and the Eyles-Weihe, cleared the rainforests and created the landscapes that still prevail in New Zealand today. As a result, all of New Zealand's large birds became extinct, so the marsh harrier (like other birds) was able to occupy a new niche in the islands' ecosystem.

hikes

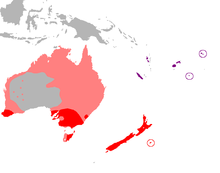

The marsh harrier lives mostly nomadic and, regardless of the season, undertakes forays, whereby they orientate themselves mainly on the food supply. She can be found as an occasional guest on almost all the islands of southern Oceania. She also undertakes longer migrations in New Zealand, where Marsh Harriers move between the North and South Islands, especially outside the breeding season. In contrast, the marsh harrier is a typical migratory bird in Tasmania and Australia .

From January, but especially from June to July, almost the entire population leaves Tasmania and the southern breeding areas and flies north to winter quarters. These are located in New South Wales , along the coast in Queensland and in the Northern Territory , and to a lesser extent in the outback and on the northwest coast of Western Australia . The first consecrations return to Tasmania around July, and the Tasmanian breeding population finally reaches its peak between October and November. The longest known distance traveled by a bird is 1,520 km (from Tasmania to northeastern New South Wales), with an average of 260 km for adults. The Australian breeding areas are mainly visited by adult harriers during the breeding season, while juvenile and immature birds remain mostly inland during this time. Marsh harrier sightings are occasionally reported from New Zealand.

In the winter quarters in the Australian state of Victoria , counts showed a bird every 0.8–1.7 km².

habitat

The marsh harrier prefers wetlands such as swamps, salt marshes, floodplains and rice fields. In the arid Australian interior, it can also be found in the vicinity of water boreholes. Basically, however, it hunts in all forms of open landscape; sheep pastures in New Zealand have become a highly frequented habitat. Heath, landscapes with isolated trees and grain fields also serve as hunting grounds for marsh harriers. The marsh harrier occurs from the coast to heights of 1200 m in Australia, 1700 m in New Zealand and 3800 m in New Guinea.

Way of life

Hunting and feeding

Marsh harriers hunt in flight over open terrain. Since they are relatively heavily built for consecration, they go over more often than other representatives of their species to circling at a great height above the ground and tumbling down on spotted prey, instead of sliding just above the ground and the prey suddenly falling out of the grass to grab. However, this has the consequence that marsh harriers are often spotted by their prey. Despite this behavior, which is more common for other species of hawk-like species , the marsh harrier does not choose high-lying perches such as hawks, but rather uses “species-typical” positions on fence posts, tree stumps or stones. However, some ornithologists such as David Baker-Gabb are of the opinion that the high search flight of the consecration serves more to look for carrion, since it is observed especially where the marsh harrier feeds on carrion to a large extent; also, it never comes down on prey from a great height, but only lets itself sink down before it grabs prey. The consecration grabs fish by flying just above the surface of the water, then suddenly thrusting down and grabbing the fish. This hunting method is particularly successful in fish ponds and other bodies of water with a high fish population. The face veil , which acts like a bell, and the enlarged middle ear enable the marsh harrier to acoustically locate prey with an accuracy of 4 °. Once the marsh harrier has killed its prey, it separates the skin with its middle and rear claws, first eats the meat under the opening and then skins the prey in order to get to the rest of the meat.

The marsh harrier orients itself strongly in its diet on the respective food supply. While carrion makes up the largest part (in the sense of biomass) of the food in autumn, winter and spring, live food predominates in summer, since this time of year the supply of insects, small birds and rabbits is greatest. Mammals, especially rabbits and hedgehogs , make up the majority (approx. 45%) of the prey . In second place are birds (approx. 36%), especially passerines , then insects (approx. 8%), eggs, mostly from floor nests (approx. 5%), and aquatic animals (approx. 5%). Marsh harriers near the coast adapt to their surroundings. For example, in addition to young little penguins ( Eudyptula minor ), they also prey on fish and shellfish .

The high proportion of hedgehogs in the diet can be attributed to the fact that they often starve to death during winter and are particularly often victims of accidents involving wildlife and are then consumed by the marsh harrier, the same applies to other medium-sized mammals. Rabbit carrots, on the other hand, can also come from control measures against these neozoa, which are pests in Australia and New Zealand . The marsh harrier usually finds these animals in rabbit traps. Among live rabbits, mainly young animals are captured, larger mammals are rarely victims of the consecration. Even among the beaten birds, smaller species dominate, especially nestlings; most of the food is captured on the ground. The capture of birds that are larger than the harrier, such as a white-cheeked heron ( Egretta novaehollandiae ) , is an absolute exception . If the marsh harrier can choose between two pieces of carrion, it usually chooses the piece that is easiest to transport; it is then dragged into the bushes, where it can eat it undisturbed. There is no evidence for the opinion, at least previously widespread in New Zealand, that the marsh harrier would also beat lambs, at the same time sheep in the form of carrion represent an important part of the diet for the birds in New Zealand. This is especially true for the winter months, when others Food sources dry up and the proportion of sheep meat in the diet rises to around 80%.

Social behavior

Occasionally it happens that marsh harriers form larger associations. In exceptional cases, at dusk, up to 150 animals can be found together on a common nesting site, on which the birds create oval sleeping nests with dimensions of around 30–36 cm × 20–26 cm. The animals form paths between the individual nests as long as the grass in the nesting area is not too high. In the morning the consecrations start again, usually only some of them return to the common nesting place. At least for larger nesting communities, an increased food supply seems to be decisive, for example after the rabbits' litter time. Smaller associations of up to ten animals can also come together without a specific reason.

Territorial behavior and settlement density

Marsh harriers occupy territories both during the breeding season and in the winter quarters. A distinction must be made between hunting grounds and hunting grounds: the former cover several hectares and are defended against intruders. The hunting areas go beyond the territorial boundaries and have an area of several square kilometers.

The male defends the territories against potential rivals through patrol flights. Both males fly slowly at a distance of about 10 m at a low altitude with strongly bent wings and clearly presented, drooping legs along the territorial boundaries. Then both fly away in different directions. Intruders are attacked and chased away at the latest from the time they lay their eggs, attacking them with the claws and pursuing them to the boundaries of the territory.

During the breeding season, males and females share a territory, the size of which can vary greatly and is also influenced by the territories of neighboring pairs. The observed area sizes are between 0.18 and 0.42 km², especially large areas shrank after the hatchings of the offspring. These territories are defended against intruders up to a height of 20 m at the borders and 30 m above the nest. The surrounding hunting areas cover an area of about 9 km², of which the inner 3 km² are used particularly extensively. These hunting areas do not contain any foreign breeding grounds, so that the birds do not have to expect any attacks when looking for food. Juvenile Marsh Harriers do not usually occupy any territories, so their hunting areas are larger and less tied to a specific location.

Investigations into the settlement density showed a density of one breeding pair per 0.5 km² for an area of New Zealand. Hunting areas overlapped by up to 70%, but the areas used primarily by only 10%. In a Tasmanian area with a high population density, nests were found along a stream at a distance of two kilometers. The location, size and shape of the breeding territories are primarily influenced by the terrain and neighboring breeding pairs and are only finally determined in the course of the breeding season.

In winter areas in Tasmania, hunting areas of 2.9–3.9 km² were observed, with an average of 3.6 km². In the extreme case, individual hunting areas overlapped up to six others, but this was put into perspective by the size of the hunting grounds over time; rarely did two birds hunt less than 500 m apart. In the majority of cases, the consecrations remained loyal to their territories in the following years, only a few birds left their territories, for example to join nesting associations. Outside the breeding season, one bird per 0.8 km² was counted in New Zealand; some areas are said to have a population density of one bird per 0.5 km².

Courtship and mating

Marsh harriers only form pairs during the breeding season; outside of the breeding season the birds live as solitary animals. The courtship is initiated by the male by rising to a great height and starting to circle there. This is followed by wave-like flight movements with exaggerated wing beats, whereby the male first lets himself fall and then shoots up again steeply. At the climax of this movement, the male performs a half or full roll and utters kii-a calls, to which the female replies with kii-o . In between, the male keeps falling in spirals. If the female joins it, the male rushes on it, whereupon the female plays a role and shows him her claws. This type of pursuit flight usually lasts 30 seconds, after which the couple lands on the ground.

The male then builds a simple nesting place, where it offers prey to the courted female by drawing attention to itself with raised wings and a chuk-chuk-chuk call. The female then flies over from a nearby seat guard and eats the food hunted by the male. This partnership feeding lasts until the eggs are laid at the end of October.

Mating is initiated by the female by landing near the male and inviting him to mate with a siiiuh call. The male then mounts the female, closing its claws and trying to balance with its wings. The copulation lasts a few seconds, then the partners separate again and the male continues his usual mating behavior.

The marsh harrier is one of the members of the circus genus in which polygyny has been observed (about 11% of cases). The male vies for available females, even if he already has a breeding partner. Each female then occupies territories and is looked after by the male, with the females being preferred in the order of their mating. The breeding success of the preferred females is therefore significantly higher than that of the subordinate. However, this polygyny is not related to the numerical ratio of the sexes in a population, but rather seems to correlate with a high food supply.

Breeding and rearing of the nestlings

The breeding season is between September and February, which is a little later than most of the other birds of prey in the region, the main breeding season is between October and December. In northern areas or during drought, the marsh harrier usually starts building nests earlier than elsewhere. The nest consists of grass, reeds and possibly also small sticks, which are put together by the female over two to six weeks on the ground or in shallow water to form a loose, dense structure. It is oval in shape, measures around 50 × 80 cm and is 40 cm above the ground. Mostly the nest is near streams and other bodies of water or in grain fields, where the vegetation protects against nest robbers and the weather; Marsh harriers only breed in trees very rarely.

The clutch consists of one to seven eggs of 3.7-5.7 × 2.8-4.2 cm, on average 5.0 × 3.9 cm in size. The average in Southeast Australia is 3.6–3.8 eggs, depending on the region, while New Zealand Marsh Harriers lay an average of 4.6 eggs, which can be explained by the lack of predators in New Zealand.

During incubation and the nestlings' complete dependency, the male alone is responsible for procuring food, while the female guards the nest. The prey is handed over in the air, with the female flying up from the nest as soon as the male returns. In flight, it sits about 1–2 m behind the male, whereupon the male pulls up abruptly and at the same time drops the prey. The prey, which floats for a short time due to inertia, is grabbed out of the air by the female by lying on her back and pushing upwards with her claws. Then the female flies to the nest with the prey. The reason for this transfer method is most likely that the marsh harrier is ground breeder and the smell of animals passed on the ground could attract nest robbers.

The chicks hatch after 31–34 days and then need around 43–46 days to fledge. During this time the male increases his food supplies. Four to six weeks after the young have hatched, the female also starts hunting again. The dependency on the parents after fledging takes between four and six weeks before the young birds have become completely independent.

Systematics

External system and history of development

Marsh harriers show in behavior, nutrition and genetic makeup a close relationship to a number of other consecrations, which prefer to inhabit wetlands and are therefore placed in a common group, the so-called "Marsh harriers". The marsh harrier is most closely related to the marsh harrier ( C. aeruginosus ) as well as the Madagascar ( C. macrosceles ) and Réunion harrier ( C. maillardi ) from the Indian Ocean, at least as far as the species of the genus Circus living today are concerned. The Eyles consecration ( C. eylesi ), which died out in the 13th century , is regarded as a close relative of the marsh harrier, with which it shares various morphological properties in addition to the New Zealand habitat. The assumption that these two species of consecration had a common ancestor is also due to the fact that the marsh harrier has so far been the only species to colonize remote islands in the Pacific, in contrast to the other Australian consecration, the spotted harrier ( C. assimilis ), which in New Zealand does not exist.

According to Robert Simmons and Michael Wink (2000), the relationships of the marsh harrier are as follows:

| Hawk species (Accipitridae) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Internal system

Two subspecies are currently distinguished for the marsh harrier , although this subdivision is controversial:

- C. a. approximans Peale , 1848 : The nominate form is native to the Loyalty Islands , New Caledonia , the Wallis Islands , Fiji , Vanuatu and the Chatham Islands .

- C. a. gouldi Bonaparte , 1850 : This subspecies is very similar in appearance to the nominate form, it is usually darker in color and the dotted lines on the underside are stronger. Its range includes New Zealand , Tasmania and mainland Australia .

The external similarity between Papua ordination ( C. spilothorax ) and Mangroveweihe ( C. spilonotus ) led to earlier than the former was considered to belong to Mangroveweihe, since the males of both species have a similar color. Later, however, some ornithologists saw a closer relationship to the marsh harrier. Since there are also great similarities to the marsh harrier in young animals and females of spilothorax , the Papuan harrier was currently listed as a subspecies by various authors.

However, this assignment remained controversial: Although James Ferguson-Lees and David Christie spoke out in 2001 in favor of the Papuan consecration belonging to the swamp consecration, they did not want to rule out the possibility that it could be an independent species. Robert Simmons, however, treated the Papuan Harrier 2000 neither as a subspecies of the Mangrove nor the Marsh Harrier, but as a species in its own right. Ferguson-Lees and Christie followed suit in 2009. The DNA of the Papuan consecration is currently being analyzed and the publication of the results is in preparation.

With respect to C. a. gouldi and C. a. approximans was David Baker-Gabb in 1979 that the small morphological differences did not allow division into one Australian-New Zealand and an oceanic subspecies. The consequence is therefore to regard both as belonging to the nominate form. On the other hand, the large spatial separation and the low mixing of the respective populations speak for a subdivision.

Duration

In New Zealand, the marsh harrier is the most common bird of prey and the marsh harrier is apparently also common on the Pacific Islands. For the respective populations of the marsh harrier in Australia, New Zealand, Oceania and especially New Guinea, only little data is available. Overall, the breeding areas of the marsh harrier cover around 1.6 million km²; Ferguson-Lees and Christie estimate the total population at several tens of thousands of birds.

Causes of Mortality, Diseases and Exposure

In addition to starvation and death from old age, the causes of mortality in marsh harriers are primarily related to humans, since adult marsh harriers have hardly any predators within their area of distribution. Because the marsh harrier had a reputation not only for beating lambs, but also for killing pheasants, quails and other birds that were released for hunting purposes in New Zealand, many birds fell victim to targeted shooting and poisoning, especially in the first half of the 20th century to the victim. Some of the so-called Acclimatisation Societies , which had set themselves the goal of settling English species in New Zealand, offered bonuses for marsh harriers that were shot. In the 1930s and 1940s the Otago Acclimatization Society alone paid rewards for 26,184 consecrations killed in seven years, and the Auckland Acclimatization Society recorded over 200,000 kills in 15 years. Sheep farmers, on the other hand, rubbed dead lambs or other bait with strychnine , causing the harriers to die immediately. Walter Lawry Buller estimated the number of consecrations that were killed in this way at several thousand animals per year at the end of the 19th century. Even today, marsh harriers are still occasionally shot, including in the protected areas of the black stilt ( Himantopus novaezelandiae ). The active hunting of rabbits from the 1950s onwards may also have contributed to a decline in New Zealand's marsh harrier population. Occasionally, individual marsh harriers are attacked by flute birds ( Gymnorhina tibicen ), and fatal attacks have also been documented.

The louse Degeeriella fusca , known from other birds of prey , also attacks the marsh harrier . Cases have been reported in New Zealand where the affected birds suffered from tongue swelling. These were caused by tendon and muscle tissue that was wrapped around the tongue. Apparently this tissue came from carrion, which could pose a problem in the medium term given the increasing dependence of New Zealand consecration on this food source. The marsh harrier's predilection for carrion also poses a problem in other respects: Since New Zealand marsh harriers prefer to feed on animals killed in accidents with wildlife, they themselves are at risk of being run over. On busy roads with a total length of 33 km, 46 consecrated consecrations were counted between June 1985 and October 1986, half of which were killed during May (mostly young birds) and July (continuous snow cover on the streets). The plumage of many harriers is also severely damaged in rabbit traps. The feathers are either broken or torn out by the traps, which leads to lasting damage in the plumage of birds of prey.

Much of the population in New Zealand is affected by lead poisoning . Studies of lead exposure in New Zealand birds showed an increased lead concentration in the blood of 60% of the marsh harriers examined. In addition to lead paint and industrial waste, lead ammunition is the main source of lead entering the environment. Lead is also associated with clinical pictures in which the birds' feet cramp and thus significantly impair them. Although lead does not appear to be the sole cause of these symptoms, harriers with cramped claws all have increased levels of lead. Above all, the preference of the marsh harrier for carrion, which comes from hunting measures, is considered fatal.

Marsh harriers are particularly endangered by the draining of wetlands and accidents involving wildlife. The IUCN lists the marsh harrier as not endangered.

The marsh harrier in mythology

In the tales of the Māori and their mythology , the marsh consecration takes on the role of an ambassador of the gods under the name of Kāhu and therefore enjoyed high esteem among the Māori in the past centuries. The Māori attributed the color of the plumage to the theft of the fire from Mahuika by Māui : The marsh harrier was scorched and its feathers turned dark.

In the mythology of some Aboriginal tribes, the marsh harrier, called joongabilbil , is associated with the gift of fire. In the stories she is inspired by the desire to bring fire to people, which she only succeeds after several attempts, until she finally sets one tree after the other on fire. Then she teaches people how to use dry wood to start a fire.

References

literature

- David John Baker-Gabb : Aspects of the biology of the Australasian Harrier. ( Circus aeruginosus approximans Peale 1848). A thesis presented for the degree of Master of Science by thesis only in Zoology at Massey University. Massey University, Palmerston North 1978.

- David Baker-Gabb: Remarks on the Taxonomy of the Australasian Harrier (Circus approximans). In: Notornis . 26, No. 4, 1979, pp. 325-329.

- David Baker-Gabb: The Diet of the Australasian Harrier in Manawatu-Rangitikei Sand Country. In: Notornis. 28, No. 4, 1981, pp. 241-254.

- David Baker-Gabb: Ecological Release and Behavioral and Ecological Flexibility in Marsh Harriers on Islands. In: Emu. 82, No. 2, 1986, ISSN 0158-4197 , pp. 71-81.

- David Baker-Gabb: Wing-tags, winter ranges and movements of Swamp Harriers Circus approximans in southeastern Australia. In: Penny Olsen (Ed.): Australian Raptor Studies. Australasian Raptor Association RAOU, Melbourne 1993, ISBN 1-875122-05-2 , pp. 248-261.

- David Baker-Gabb: Auditory location of prey by three Australian raptors. In: Penny Olsen (Ed.): Australian Raptor Studies . Australasian Raptor Association RAOU, Melbourne 1993. pp. 295-298.

- Walter Lawry Buller : A History of the Birds of New Zealand. 2 volumes. Self-published, London 1888, pp. 204-212.

- Les Christidis , Walter E. Boles: Systematics and taxonomy of Australian birds. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood 2008, ISBN 978-0-643-06511-6 , pp. 117-118.

- John FM Fennel: An Observation of Carrion Preferrence by the Australasian Harrier ( Circus approximans gouldi ). In: Notornis. 27, No. 4, 1980, pp. 404-405.

- James Ferguson-Lees , David A. Christie : Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston MA 2001, ISBN 0-618-12762-3 , pp. 144-145, pp. 503-505.

- James Ferguson-Lees, David A. Christie: Birds of Prey of the World. Franckh-Kosmos Verlag, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-440-11509-1 , p. 150.

- Nick C. Fox: Some morphological data on the Australasian Harrier (Circus approximans gouldi) in New Zealand. In: Notornis. 24, No. 1, 1977, pp. 9-19.

- LA Hedley: Some observations of a communal roost of the Australian Harrier. In: Notornis. 23, No. 2, 1976, pp. 85-89.

- Penny Olsen, TG Marples: Geographic Variation in Egg Size, Clutch Size and Date of Laying of Australian Raptors (Falconiformes and Strigiformes). In: Emu. 93, No. 3, 1993. pp. 167-179.

- RJ Pierce, RF Maloney: Responses of Harriers in the MacKenzie Basin to the abundance of rabbits. In: Notornis. 36, No. 1, 1989, pp. 1-12.

- RE Redhead: Some aspects of the feeding of the harrier. In: Notornis. 16, No. 4, 1969. pp. 262-284.

- Michael Sharland: The Swamp Harrier as a Migrant. In: Emu. 58, No. 2, 1958. pp. 74-80.

- Robert E. Simmons: Harriers of the World: Their Behavior and Ecology (= Oxford Ornithology Series 11). Oxford University Press, Oxford u. a. 2000, ISBN 0-19-854964-4 .

- Robert E. Simmons, Leo AT Legra: Is the Papuan Harrier a globally threatened species? Ecology, climate change threats and first population estimates from Papua New Guinea. In: Bird Conservation International. 19, No. 1, 2009, ISSN 0959-2709 , pp. 1-13.

- Andrew M. Tollan: Maintenance Energy Requirements and Energy Assimilation Efficiency of the Australasian Harrier. In: Ardea . 76, No. 2, 1988, pp. 181-186.

- Jennifer Marie Youl: Lead Exposure in Free-ranging Kea (Nestor notabilis), Tahake (Porphyrio hochstetteri) and Australasian Harriers (Circus approximans) in New Zealand. A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Veterinary Science in Wildlife Health at Massey University. Massey University, Palmerston North 2009, pp. 1-31 u. 87-108.

Web links

- Narena Olliver: Kahu, the harrier hawk www.nzbirds.co.nz

- Literature on marsh harrier in the Global Raptor Information Network

- Circus approximans onthe IUCN Red List of Endangered Species . Listed by: BirdLife International, 2008. Retrieved November 26, 2009.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings on Circus approximans in the Internet Bird Collection

Individual evidence

- ↑ David Baker-Gabb: The Diet of the Australasian Harrier in Manawatu-Rangitikei Sand Country. In: Notornis. 28, No. 4, 1981, pp. 241-254.

- ^ A b c d Neil Hetherington : Species Profile: Australasian Harrier . Canterbury Nature , 2006, archived from the original on May 26, 2009 ; accessed on May 16, 2019 (English, original website no longer available).

- ^ Robert E. Simmons: Harriers of the World: Their Behavior and Ecology. Oxford University Press , 2000, ISBN 0-19-854964-4 , p. 35

- ↑ James Ferguson-Lees, David A. Christie: Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001, ISBN 0-618-12762-3 , pp. 503-505.

- ↑ a b Ferguson-Lees u. Christie 2001, pp. 145, 504-505.

- ↑ Nick C. Fox: Some morphological data on the Australasian Harrier (Circus approximans gouldi) in New Zealand. In: Notornis. 24, No. 1, 1977, p. 10 ( online ; PDF; 2.5 MB).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001, pp. 504–505.

- ^ Walter Lawry Buller: A History of the Birds of New Zealand. 1888. p. 207. ( online ; e-book)

- ^ A b David Baker-Gabb: Aspects of the biology of the Australasian Harrier. ( Circus aeruginosus approximans Peale 1848): a thesis presented for the degree of Master of Science by thesis only in Zoology at Massey University. Massey University, 1978. pp. 21 & 26.

- ↑ a b Fox 1977, p. 11.

- ↑ Simmons 2000, pp. 97-124.

- ^ A b David Baker-Gabb: Ecological Release and Behavioral and Ecological Flexibility in Marsh Harriers on Islands. In: Emu 82, No. 2 1986, pp. 71-81.

- ↑ a b c Baker-Gabb 1978, p. 33.

- ↑ C. Blanvillain et al. a .: Impact of introduced birds on the recovery of the Tahiti Flycatcher ( Pomarea nigra ), a critically endangered forest bird of Tahiti. In: Biological Conservation 109, No. 2, February 2003. pp. 197-205.

- ^ F. Harrison, M. Lewis: Swamp Harriers breeding in North Queensland. In: Australian Bird Watcher 17, 1997. pp. 102-103.

- ^ DG Gosper: Breeding of the Swamp Harrier on the NSW north coast. In: Australian Birds 27, 1994. p. 151.

- ^ A b Trevor H. Worthy, Richard N. Holdaway: Quaternary fossil faunas, overlapping taphonomies, and palaeofaunal reconstruction in North Canterbury, South Island, New Zealand. In: Journal of The Royal Society of New Zealand , Vol. 26, No. 3, 1996, pp. 275–361 (Online as PDF (10.1 MB) ( Memento from October 22, 2008 in the Internet Archive )).

- ^ A b Trevor H. Worthy, Richard N. Holdaway: The Lost World of the Moa. Prehistoric Life of New Zealand. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 2002, ISBN 0-253-34034-9 , p. 355.

- ↑ a b Michael Sharland: The Swamp Harrier as a Migrant. In: Emu 58, No. 2, 1958. pp. 74-80.

- ^ Nick Mooney: Status and Conservation of Raptors in Australia's Tropics. In: Journal of Raptor Research. 32, No. 1, 1998, p. 67.

- ↑ Penny Olsen, TG Marples: Geographic Variation in Egg Size, Clutch Size and Date of Laying of Australian Raptors (Falconiformes and Strigiformes). In: Emu 93, No. 3, 1993, p. 168.

- ^ RE Redhead: Some aspects of the feeding of the harrier. In: Notornis 16, No. 4, 1969. pp. 278-280. (Online as PDF (4.4 MB) )

- ↑ Simmons 2000, p. 53.

- ^ A b Fergus Clunie: Harriers fishing. In: Notornis. 27, No. 2, 1980, p. 114 (online as PDF (5.0 MB) ).

- ^ David Baker-Gabb: Auditory location of prey by three Australian raptors. In: Penny Olsen (Ed.): Australian Raptor Studies . Australasian Raptor Association, RAOU Melbourne 1993. pp. 295-298.

- ↑ a b Baker-Gabb 1979, pp. 248-249.

- ↑ A. David, M. Latham: Australasian harrier (Circus approximans) observed feeding on crabs at Hooper's Inlet, Otago Peninsula. In: Notornis. 49, No. 1, 2002. pp. 53-54 (online as PDF (95 kB) ).

- ↑ David J. Hawke, John M. Clark, Chris N. Challies: Verification of seabird contributions to Australasian harrier diet at Motunau Island, North Canterbury, using stable isotope analysis. In: Notornis. 52, No. 2, 2005 pp. 158–162, online PDF 526 kB

- ^ John FM Fennel: An Observation of Carrion Preferrence by the Australasian Harrier ( Circus approximans gouldi ). In: Notornis. 27, No. 4, 1980, pp. 404-405 (online as PDF (3.8 MB) ).

- ↑ Redhead 1969, p. 269.

- ↑ LA Hedley: Some observations of a communal roost of the Australian Harrier. In: Notornis. 23, No. 2, 1976, pp. 85-89 (online as PDF ( memento of October 18, 2008 in the Internet Archive ); 5.0 MB).

- ↑ a b c d Baker-Gabb 1977, pp. 27-30.

- ^ David Baker-Gabb: Wing-tags, winter ranges and movements of Swamp Harriers Circus approximans in southeastern Australia. In: Penny Olsen (Ed.): Australian Raptor Studies . Australasian Raptor Association, RAOU Melbourne 1993. pp. 248-261.

- ↑ Baker-Gabb 1978, pp. 31-32.

- ↑ a b Baker-Gabb 1978, pp. 34-35.

- ↑ Simmons 2000, p. 34 and 92.

- ↑ Baker-Gabb 1978, p. 36.

- ↑ Simmons 2000, pp. 276-277.

- ↑ Redhead 1969, p. 281.

- ↑ Olsen 1993, p. 170.

- ↑ Baker-Gabb 1978, pp. 39-40.

- ↑ a b Narena Olliver: Kahu, the harrier hawk www.nzbirds.co.nz. July 11, 2005. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ↑ Simmons 2000, pp. 43-49.

- ↑ Les Chrisitidis, Walter Boles: Systematics and taxonomy of Australian birds. CSIRO Publishing, 2008, ISBN 0-643-06511-3 , pp. 117-118.

- ↑ a b Simmons 2000, p. 25.

- ↑ Simmons 2000, p. 22.

- ^ Robert E. Simmons, Leo AT Legra: Is the Papuan Harrier a globally threatened species? Ecology, climate change threats and first population estimates from Papua New Guinea. In: Bird Conservation International. 19, No. 1, 2009, pp. 1–13, doi: 10.1017 / S095927090900851X , online ( Memento from May 3, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) PDF 468 kB

- ^ David Baker-Gabb: Remarks on the Taxonomy of the Australasian Harrier (Circus approximans). In: Notornis. 26, No. 4, 1979, pp. 327-329 (online as PDF (4.8 MB) ).

- ^ David John Baker-Gabb: The Diet of the Australasian Harrier in Manawatu-Rangitikei Sand Country. In: Notornis. 28, No. 4, 1981, pp. 241-242 (online as PDF (5.0 MB) ).

- ^ Dai Morgan, Joseph R. Waas, John Innes: Magpie interactions with other birds in New Zealand: results from a literature review and public survey. In: Notornis . 52, No. 2, 2005, pp. 61–74 (online as PDF (1.2 MB) ).

- ↑ Buller 1888, p. 209.

- ↑ Fox 1977, pp. 15-18.

- ^ RJ Pierce, RF Maloney: Responses of Harriers in the MacKenzie Basin to the abundance of rabbits. In: Notornis 36, No. 1, 1989, p. 9.

- ↑ Jennifer Marie Youl: Lead Exposure in Free-ranging Kea ( Nestor notabilis ), Tahake ( Porphyrio hochstetteri ) and Australasian Harriers ( Circus approximans ) in New Zealand. Massey University, Palmerston North 2009. pp. 1-31 u. 87-108.

- ^ Circus approximans in the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species . Listed by: BirdLife International, 2008. Retrieved November 26, 2009.

- ↑ Narena Olliver: Maori Myths. www.nzbirds.com, 2005. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ↑ IM Odenberg: Aboriginal Tales Retold. www.theosophy-nw.org. Retrieved January 12, 2010.