North Atlantic Oscillation

In meteorology, the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) is understood to mean the fluctuation of the pressure ratio between the Iceland low in the north and the Azores high in the south over the North Atlantic .

Basics

This term was first coined in 1923 by Sir Gilbert Walker .

An international team led by Thomas Felis and Gerrit Lohmann from the DFG Research Center Ocean Margins at the University of Bremen has used coral studies to show that the climatic duo of the Iceland low and the Azores high determined the weather in Central Europe and the Middle East during the last warm period 122,000 years ago .

NAO index

The NAO is defined as a dimensionless index . This index correlates with the strength of the westerly winds over the North Atlantic, the storm intensity and region over the North Atlantic and the precipitation in Eurasia. The NAO thus plays a decisive role in continental European weather and climate.

The NAO index is usually based on the difference between the standardized air pressure - anomalies between Lisbon , Gibraltar and Ponta Delgada ( Azores ) and Reykjavik ( Iceland ).

Modern variants are based on numerical weather models and take the overall climate situation into account. The long-term monthly mean of the 500 hPa altitude anomaly in the Atlantic area from 20 ° north latitude to the North Pole is calculated , a statistical main component analysis is carried out for the mean position of the air masses (Emperical Orthogonal Function, EOF and Rotated Principal Component Analysis, RPCA), and above the variance is determined. The NAO index is the interpolated mean daily deviation from this monthly base value. This methodology also takes into account the influences of all other known teleconnection patterns .

Phases of the NAO

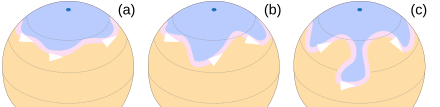

Like all currents, the NAO can be divided into two (?) Phases:

- positive: If the NAO index is positive, the action centers , both Azores high and Iceland low, are well trained. In most cases this leads to a strong westerly wind drift and rapidly changing general weather conditions

- neutral - a distinction must be made between two cases:

- either moderate development of both action centers with average weather events

- or a strong Azores high and weak Iceland low or vice versa. This leads to abnormal shifts in climatic influences to the north or south.

- negative: With a negative NAO index, both the Azores high and Iceland low are only weakly pronounced. The west wind drift has largely "fallen asleep", there are blockages with stable weather conditions (good and bad weather)

- strongly negative (reversal): If the Azores high has taken the place of the Iceland low and vice versa, the NAO index is strongly negative. This is known as the high-over-low location .

If the NAO index changes rapidly from positive to negative and vice versa, the dynamics of the centers of action and the rapid displacement of air masses also lead to more extreme weather.

Fluctuation periods

The NAO index changes significantly over time. Various types of temporal changes can be derived from the statistical data.

The variance of the monthly NAO base indices is small in late winter and autumn (around 0.5), neutral in midwinter (around 1) and fluctuates more strongly in the summer half-year, with peaks for May, July and September (between 1 and 2). That represents the stability of the weather conditions .

In addition to the short-term fluctuations in the range of a few days (weather conditions) and the seasons, there are also periods of several years of 2 to 5 years (perhaps correlated with the quasi-two-year oscillation ), and superimposed periodic fluctuations with a rhythm of 12 to 15 years (decadal oscillation ) and about 70 years ( Atlantic Multidecade Oscillation , AMO).

If the NAO index changes significantly over periods of 30 years and more, the climate in Europe is also affected.

Consequences for the environment and climate

The consequences vary depending on whether the NAO is positive or negative.

Consequences of a positive NAO

The atmosphere:

- In Greenland , the polar air determines the weather, so it is particularly cold and dry.

- The west wind drift brings mild and humid air ( Atlantic air masses) to Europe. Characteristic is the often regular alternation of good and bad weather phases lasting several days with the fronts of the North Atlantic lows and intermediate highs .

- The jet stream , a wind system that blows around the globe several kilometers above the ground at about 30 ° to 60 ° north latitude, is influenced by the Icelandic Depression in such a way that the low pressure areas formed over the Atlantic with their strong winds directly reach Northern Europe. Heavy precipitation and mild temperatures are the result in the temperate latitudes of Europe. In this situation, Central Europe can be hit by winter storms . This happened for example in 1999 ( Anatol , Lothar , Martin ).

- Meanwhile, cold foothills of the Russian high often reach the Mediterranean. Accordingly, it will be colder and drier than usual there.

- The trade winds are increasing over North Africa .

Ocean:

- Ice exports from the Arctic seem to be getting bigger than normal due to the cold weather in Greenland.

- The surface temperature shows a three-pole structure: The Labrador Sea becomes particularly cold due to the cold winter storms, while the Gulf Stream region warms up when the Gulf Stream (and its branch, the North Atlantic Current) transports more warm water northwards.

- The increased trade winds lead to a cooling of the equatorial Atlantic due to increased upwelling from the deeper ocean.

Biological processes:

- In Scandinavia, the flora and fauna have about 20 more days to flourish before the frost sets in.

- In the Labrador Sea, the sinking of the cold surface water is leading to a decline in fish populations (especially cod and cod).

- The strong trade winds mean that the sand of the Sahara blows far out into the Atlantic. The influence of this dust on the biology in the ocean is not fully understood.

- The surface water that is driven away from the African coast is being replaced by more nutrient-rich deep water from the deeper ocean, so there is a lot of fish that gives fishermen a good catch.

Consequences of a negative NAO

The atmosphere:

- In Greenland it gets relatively warm, because the weak low does not counteract the warm air currents from the American mainland .

- The westerly winds over the Atlantic are weaker due to a weaker contrast in air pressure. You hardly reach Northern Europe, but rather the Mediterranean area . In Central Europe, cold air ingress from the northeast can increase, which leads to cold weather, or with a south-westerly high-altitude current to subtropical influence and warmth.

- Northern Europe comes under the influence of the high cold over Asia in winter . The result is weather conditions with low temperatures and little precipitation. If the index is strongly negative, these penetrate far into Central Europe via Russia and bring heat to Central Europe in summer and cold in winter.

- The weakened west wind drift is shifting southwards and leads to wetter weather in the Mediterranean area.

- Atmospheric blockages arise with long-lasting large-scale weather conditions, up to heat or cold waves .

Ocean:

- The ice sheets in the Arctic seem to be retreating, as are the glaciers on Greenland. However, this happens much more slowly than the NAO fluctuates.

- The three-part structure in the North Atlantic has turned around: The warmer mainland air in the Labrador Sea ensures that this area becomes warmer. It stays rather cool off the east coast of the USA because the now weaker Gulf Stream shovels less warm water to the north.

- The trade winds along the equator are weaker, so that there is less cooling there.

Biological processes:

- The colder water in the area of the Gulf Stream allows the stock of mussels to grow there.

- In the Labrador Sea, the fish stocks increase due to higher temperatures.

- Increased rainfall in the Mediterranean region favors wine and olive harvests.

The NAO as an influencing factor for deep water transport

The vertical water exchange that takes place in the North Atlantic in both the Labrador Sea and the European Arctic Ocean is significantly influenced by fluctuations in the NAO. The predominantly positive NAO situations in the last two decades have led to an increased formation of deep water in the Northwest Atlantic. This correlates with the relatively cold winter temperatures that occur on the east coast of Canada due to the positive NAO location. The convective renewal of medium and deep water layers in the Labrador Sea contributes to the production and transport of the North Atlantic deep water and thus keeps the global thermohaline circulation going. The intensity of the convection currents occurring in the North Atlantic is influenced less by seasonal fluctuations than by fluctuations in the NAO that extend over decades. In the late 1960s, the convection in the Labrador Sea was much weaker and therefore flatter than it is today. Since then, the water of the Labrador Sea has become a lot colder and salty, with greatly increased convection currents down to a depth of over 2,300 meters. In contrast, convection in the European Arctic Ocean has been suppressed in recent years and is characterized by warmer and more salty deep waters.

Remote effects

The North Atlantic Oscillation and the Arctic Oscillation (AO) are spatially very similar and therefore cannot be considered separately, with the AO extending more comprehensively to the North Pole in the North Pacific. The AO index tends to primarily describe the ratio of the Azores high to the Iceland low, the NAO index the intensity of both centers of action compared to the standard pressure.

There appears to be a connection between the NAO and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). Decades with a high winter NAO index coincide with decades with a high PDO index. This means that in the decades with many La Niña events, severe winters can be expected in Europe. The period from 1945 to 1970 supports this thesis. It remains to be investigated whether there is a possible cause ( teleconnection via the North Pole and the American land masses in the course of the westerly wind drift ), which can have a decisive influence on both oscillations.

It is important, however, that the Southern Oscillation (SO) does not seem to have any direct impact on the NAO. Investigations of the correlation between winter in Europe and the SE show that only temperature changes below 1/10 ° C are to be taken into account. In summer this is even less. The SO is therefore more of a great relative of the NAO, or perhaps a consequence of the Pacific weather engine that has been decoupled by the tropics.

Today it is assumed, however, that the cycles of the El Niño / La Niña events ( El Niño-Southern Oscillation , ENSO) influence those of the NAO. The northern and southern hemispheres are affected by the ENSO. Therefore, according to the current state of research, the ENSO is considered to be a fundamental “weather engine”.

See also

- Arctic Oscillation (AO)

- El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)

- Pacific Decade Oscillation (PDO)

- Southern Oscillation Index (SO)

literature

- David B. Stephenson, Heinz Wanner , Stefan Brönnimann, Jürg Luterbacher: The History of Scientific Research on the North Atlantic Oscillation . In: James W. Hurrell, Yochanan Kushnir, Geir Ottersen and Martin Visbeck (Eds.): The North Atlantic Oscillation: Climatic Significance and Environmental Impact . Wiley, 2003, doi : 10.1029 / 134GM02 ( ex.ac.uk [PDF; 4.5 MB ]).

media

- Azores high & Iceland low . Series universe . Kurt Mayer (book), Dieter Pochlatko (producer), Andreas Jäger (moderation), Kurt Adametz (music); ORF , undated ( shop.orf.at )

Web links

- Daily North Atlantic Oscillation Index. Climate Prediction Center (cpc.ncep.noaa.gov) - Current values and forecasts of the AO

- NAO / AO / Gulf Stream. Thomas Sävert, naturgewalten.de

- NAO, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

- Description of the Climate Analysis Group in the Department of Meteorology at the University of Reading

- NAO page of the Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research Kiel (GEOMAR)

- The North Atlantic Oscillation - Steering the Winter; Publication at the Meteorological Institute of the Free University of Berlin, PDF format

Individual evidence

- ↑ A climate swing makes a career. The North Atlantic Oscillation . Part 6 of weblink scinexx

- ^ The climate from the air pressure swing, Max Planck Society, mpg.de → Climate Research, May 14, 2004

- ↑ North Atlantic: Climate swing 120,000 years old , springer.com → Geosciences & Geography (review of the article in nature 2004)

- ↑ James W. Hurrel: The North Atlantic Oscillation: Climatic Significance and Environmental Impact. Ed .: American Geophysical Union. 2003, ISBN 978-0-87590-994-3 .

-

↑ a b c Teleconnection Pattern Calculation Procedures: 2. North Atlantic Oscillation / Pacific - North American pattern (NAO / PNA). cpc.ncep.noaa.gov > Monitoring Weather & Climate> Teleconnections;

and Technique for Identifying the Northern Hemisphere Teleconnection Patterns. cpc.ncep.noaa.gov > Monitoring and Data> Oceanic & Atmospheric Data> Northern Hemisphere Teleconnection Patterns (both accessed November 25, 2017). - ↑ Group for Meteorology and Climatology at the University of Bern, Klimet ( Memento from January 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive )