Orontea

| Opera dates | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Orontea |

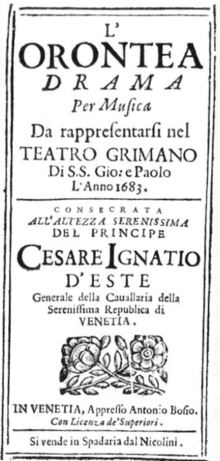

Title page of the libretto, Innsbruck 1656 |

|

| Shape: | Dramma musicale in a prologue and three acts |

| Original language: | Italian |

| Music: | Antonio Cesti |

| Libretto : | Giacinto Andrea Cicognini , Giovanni Filippo Apolloni |

| Premiere: | February 19, 1656 |

| Place of premiere: | Hall Theater Innsbruck |

| Playing time: | about 3 hours |

| Place and time of the action: | Paphos , antiquity |

| people | |

|

Prolog:

Action:

|

|

Orontea (also L'Orontea ) is an opera (original name: "Dramma musicale") in a prologue and three acts by Antonio Cesti (music). The libretto is by Giacinto Andrea Cicognini . It was reworked for Cesti's setting by Giovanni Filippo Apolloni. The world premiere took place on February 19, 1656 in the Saaltheater Innsbruck .

action

Orontea, the Queen of Egypt falls in love with Alidoro, a handsome young stranger who was seriously injured in a robbery and who appears at their court with his mother Aristea. The court advisor Creonte urgently advises Orontea against this improper relationship. The other women also fall in love with Alidoro: the lady-in-waiting Silandra, who separates from her lover Corindo for his sake, and Giacinta, who appears as a man under the name Ismero, who had previously carried out the unsuccessful assassination attempt on him on behalf of the Phoenician Queen Arnea. Aristea, in turn, falls in love with the supposed Ismero. The young page Tibrino and the drunkard Gelone as a comic figure combine the different storylines. The confusions of love are resolved when Alidoro is identified as a Phoenician prince through a medallion. Since he is equal to Orontea, he can marry her. Silandra and Corindo are also reunited.

The following table of contents follows the version recorded by René Jacobs in 1982. It is based on the Cambridge manuscript, which was probably made for a Venetian performance in 1666, as well as a few other pieces from probably more recent Italian manuscripts. The corresponding scene numbers of the librettos available at librettidopera.it are given in brackets .

prolog

( librettidopera.it contains the Venetian prologue from 1649.)

The allegories of philosophy (Filosofia) and love (Amore) argue violently. Filosofia despises all pomp as well as war and love. For them, only virtue counts in poverty. Amore thinks this attitude is folly. He points to his own great importance with the people. The two agree to a competition in Egypt, where they want to apply their respective influence on the court philosopher Creonte.

first act

Village

Scene 1. The Egyptian queen Orontea is determined not to allow love to dominate her (Orontea: “Superbo Amore al mondo imperi”). She prefers to rule alone.

Scene 2. Creonte points out to Orontea that the people expect her to choose a husband. So far, however, she has rejected all applicants. Orontea insists on her freedom (Orontea: "Io ch'amore in sen non ho" - Orontea / Creonte: "Io prevedo rovine").

Scene 3. Page Tibrino tells Orontea that he has just saved a handsome young man (Alidoro) from an assassination attempt. However, the attacker escaped because he had to take care of the wounded.

Scene 4. Alidoro and his mother Aristea ask Orontea for help. All they know of the assassin is that he had claimed to be acting on behalf of Princess Arnea of Phenicia. Orontea has Alidoro brought to the palace for care.

Scene 5. Orontea wonders about her strong feelings for Alidoro (Orontea: “Ardo, lassa, o non ardo” , originally: “Un impero, che mi tira” ).

Royal apartments

Scene 6. The servant Gelone sings about his love for wine (Gelone: "Chi non beve, vita breve goderà").

Scene 7. The young courtier Corindo arrives and raves about his beautiful lover (Corindo: "Com'è dolce il vezzeggiar" - Gelone: "Quant'è dolce il rimirar").

Scene 8. Corindo's girlfriend, the lady-in-waiting Silandra, also appears (Silandra: “Come dolce m'invaghì”). The flirtation of the two bothers the drunkard. When the queen appears, everyone withdraws.

(Garden)

Scene 9. Alidoro, who has completely recovered, tells Orontea his life story: He is the son of a pirate and has accepted a position as a royal painter at the court of Phenicia. There the princess Arnea fell in love with him, so that he had no choice but to flee Phenicia. Now Arnea seems to be pursuing him vengefully. Orontea promises him her protection, but becomes entangled in contradictions because she has no control over her own feelings. She moves away.

Scene 10. Alidoro is concerned about Orontea's strange behavior (Alidoro: “Destin plàcati un dì”).

Scene 11. Silandra notices the beautiful Alidoro and falls in love with him on the spot. Alidoro is flattered. Although he believes that she already has another admirer, he lets himself be charmed by her (Alidoro / Silandra: "Donzelletta vezzosetta").

Royal court

Scene 12. Gelone can't sleep. He fantasizes about being shipwrecked at sea.

Scene 13. Tibrino calls Gelone to the queen. Gelone thinks he has to audition (Gelone: "E là, e là, zi zi. Suonasi il harpsichord"). Only when Tibrino tempts him with wine is he ready to follow him.

( Scene 14: In a seaport, the allegories of pride (Superbia) and modesty (Pudicizia) argue about which of them will triumph over Oronteas' heart.)

Second act

garden

Scene 1. Orontea can no longer resist her love for Alidoro (Orontea: "S'io non vedo Alidoro").

Scene 2. Silandra announces the arrival of a stranger asking for an audience.

Scene 3. The stranger is actually a woman, Orontea's former lady-in-waiting Giacinta, who disguised herself as a man. She had been captured by the Cyrenian King Evandro, who fell in love with her. Giacinta accepted it in pretense, but then fled in men's clothing under the name Ismero to Phenicia to the court of Arnea, from whom she received the order to pursue and kill Alidoro. Orontea, terrified, reaches for her sword.

Scene 4. Creonte prevents Orontea's vigilante justice. He points out that it is not a ruler's job to personally punish criminals. He also believes that her anger is just "love turf" for Alidoro. Orontea sends Giacinta away.

Scene 5. Creonte confronts Orontea about her new passion, which is already a topic of conversation across the empire. Alidoro is not worthy of her. Orontea insists on her love for Alidoro. Both go.

Scene 6. Old Aristea also dreams of love (Aristea: “Se amor insolente per vaga beltà”).

Scene 7. When Giacinta appears, still disguised as a man, Aristea tries to seduce her. Giacinta points out that she does not have the right equipment for the role of a lover. Aristea is deeply disappointed.

( Scene 8: Aristea is determined not to be discouraged by the rejection.)

Ground floor hall with statues

Scene 8 (9) . Silandra is determined to leave Corindo to enter into a relationship with Alidoro (Silandra: "Addio, Corindo, addio").

Scene 9 (10) . When Corindo appears full of anticipation for the rendezvous, Silandra gives him the pass and leaves the room.

Scene 10 (11) . Corindo feels betrayed by Silandra (Corindo: "O cielo, a che son giunto?").

Scene 11 (12) . Alidoro wants to capture Silandra's beauty on canvas. Tibrino brings him his easel.

Scene 12 (13) . Silandra takes a seat for the portrait. While Alidoro begins his work, Tibrino philosophizes about women.

Scene 13 (14) . Orontea is outraged that Alidoro is having fun with Silandra. She forbids the two to interact with each other. Orontea, Tibrino and Silandra leave the scene.

Scene 14 (15) . Alidoro is so shocked by the Queen's behavior that he faints.

Scene 15 (16) . The finally rested Gelone lets his dream pass by when he finds the unconscious Alidoro. He takes the opportunity to search him for valuables.

Scene 16 (17) . Orontea catches Gelone leaning over Alidoro. She chases him away.

Scene 17 (18) . Since Orontea does not dare to openly confess her love to Alidoro, she puts her diadem on the sleeping man's head, puts a scepter on it and writes him a love letter (Orontea: "Intorno all'idol mio").

Scene 18 (19) . Alidoro wakes up, reads the letter and realizes the queen's love. He decides to dump Silandra and sees himself at Orontea's side as the new king.

( Scene 20: Amore compares his art to that of a doctor.)

Third act

Pleasure garden in the city with a fountain

Scene 1. Desperate Silandra ignores Orontea's order and greets her former lover Alidoro.

Scene 2. Alidoro doesn't want anything to do with Silandra anymore. His thoughts are only for Orontea.

Scene 3. Tibrino and Gelone are amazed at the unrest at court and in the city caused by Orontea's love. They prefer to stick with the sword or the wine (Tibrino / Gelone: “Amore attendi a te”).

Scene 4. Creonte reproaches Orontea for her improper relationship with Alidoro and his boasting. He makes her promise to banish Alidoro from the court (Creonte: "O riverita, o grande").

( Scene 5: Orontea complains of her suffering.)

Scene 5 (6) . Orontea accuses Alidoro of his arrogance, lets him return her letter and tears it up.

( Scene 7: Alidoro decides to comfort himself with Silandra.)

Scene 6 (8-9) . Alidoro apologizes to Silandra and swears her eternal loyalty. She rejects him. He laments the fickleness of women (Alidoro: "Il mondo così va").

Derelict courtyard

Scene 7 (10) . Gelone is on his way to Corindo because Silandra has asked him to put in a good word for her. Corindo still has strong feelings for Silandra.

Scene 8 (11) . Gelone hands Corindo Silandra's letter, in which she begs his forgiveness. Corindo wants to show strength and declares that he will only accept it again after the death of his rival. Gelone, too, does not speak well of the smug Alidoro.

Scene 9 (12-13) . Tibrino joins the conversation. If necessary, he wants to defend Alidoro by force. Gelone explains to him why Corindo wants to kill Alidoro. He himself is afraid of a fight and runs into the next tavern to be on the safe side.

( Scene 14: Aristea longs for Ismero.)

Scene 10 (15–17) Now Giacinta has also fallen in love with Alidoro. She does not dare to reveal herself to him, but seeks advice from Aristea. The latter promises her consolation and a diamond-studded medallion, but in return wishes for a kiss from Giacinta, who still appears as Ismero (Aristea: "Dolce cor mio, mio bel tesoro"). Giacinta apparently agrees to accompany Aristea, who revels in anticipation of the delights of love, into her rooms. Aristea believes that gold is the key to love (Aristea: "Nel regno d'Amore").

( Scene 18: Corindo is annoyed with his rival Alidoro.)

Hall in the Royal Palace

Scene 11 (19-20) . Tibrino brings Corindo a letter addressed to him, which he found with the queen. Alidoro challenges Corindo to a duel. Corindo is outraged by this arrogance of a lowly plebeian.

Scene 12 (21) . Alidoro forgives Giacinta for the assassination attempt because she is a wife and servant of Orontea. Giacinta tells him about his mother's advances and gives him the medallion she received. She secretly hopes that it will reach his heart.

Scene 13 (22-23) . Alidoro wonders about his foolish mother. Gelone watches him look at the locket. He recognizes the royal coat of arms, believes that Alidoro has stolen it, and calls for help.

Scene 14 (24) . Corindo tells Orontea of Alidoro's degrading demand. Orontea decides to remedy the problem and declare Alidoro a nobleman.

Scene 15 (25) . Creonte interrupts Orontea with the revelation that Alidoro is a common thief and therefore does not deserve a title of nobility.

Scene 16 (26) . Silandra adds that Alidoro stole Orontea's locket.

Scene 17 (27) . Gelone adds that he himself saw the said locket at Alidoro.

Scene 18 (28-29) . Tibrino reports that Alidoro has been arrested and will be coming immediately. He asked for a careful investigation into the allegations. Alidoro is brought about. Orontea and Creonte recognize the medallion as the one Creonte once received from Orontea's father Ptolemy. Alidoro explains that he received it from Ismero.

Scene 19 (30) . Giacinta / Ismero confirms Alidoros statement and assures that Aristea gave her the medallion.

Scene 20 (31) . Aristea says that she received the locket from her husband, the pirate Ipparco. A boy kidnapped by him in the Red Sea carried it with him. She then raised this boy, Alidoro, like her own child. Creonte recalls that the son of the Phoenician queen Irene was once kidnapped at sea. This child had previously received the same medallion from Ptolemy as he and Orontea. Aristea can still remember the name of the boy's wet nurse, who died shortly afterwards from her injuries. So Alidoro is Floridano, son of the King of Phenicia and brother Arneas. Thus there are no more class differences between him and Orontea. Without further ado she declares him her husband and marries Silandra to Corindo. Everyone celebrates the happy ending (Orontea / Alidoro / Silandra / Corindo: “Per te, mio respir” - final chorus: “Castissimi amori”).

layout

Instrumentation

The original orchestra for the opera consists of a three-part string ensemble plus basso continuo :

libretto

The libretto Cicogninis has a stringent dramatic structure. The characters, especially Orontea and Alidoro, are well designed psychologically. They are real emotional people, not gods. The eponymous Orontea dominates the plot. She is torn between her feelings of love for Alidoro and her sense of duty. The opportunist Alidoro, on the other hand, changes lovers depending on the situation. Reminiscent of the Commedia dell'arte , Gelone is one of the first buffo characters in opera history to take part in the actual plot. As in contemporary Spanish theater, there is dramatic intrigue and a rapid succession of dialogues. The serious and comical scenes are closely interlinked.

The aria forms in the libretto are inconsistent and for the most part irregular. A wide variety of meters can often be found within a stanza. The stresses are sometimes on the last and sometimes on the penultimate syllable.

music

Cesti makes good use of Cicognini's fluid text with its irregular arias. The constant change in metric gives the music a “tangible, concrete theatrical effect.” The recitatives are also composed smoothly according to the libretto. The most expressive scenes predominantly consist of recitatives. These include Alidoro's first encounter with Orontea (first act, scene 4), his first monologue (first act, scene 10), Orontea's argument with Creonte (second act, scene 5) and Orontea's outburst of anger (second act, scene 14). There are a great number of different types of conflicts and expressive values.

His music is more musical than the works of the older Venetian school, which are based on the “recitar cantando” (reciting singing). The aria is given greater weight and can now be clearly distinguished from the recitative.

In the first act, Cesti used parts of the music from the seventh in the following eighth scene. In both, the music of the arias also appears in the subsequent ritornelles . The rapprochement between Alidoro and Silandra (“Donzelletta vezzosetta”, first act, scene 11) takes place within the framework of a polyphonic aria of variations with three-part ritornello. The first stanza of Silandra's solo scene "Addio, Corindo, addio" (second act, scenes 8–9) is in double the meter of the second, the introduction of which it forms. The latter is an orchestral ostinato aria over a bass line formed from a descending tetrachord . Orontea's aria “Intorno all'idol mio” (second act, scene 17) is the most famous piece of the opera.

Work history

Cestis Orontea, together with his operas La Dori and Francesco Cavallis Giasone, is one of the most popular operas of the 17th century. Their success is due to the human characters, the believable plot, the lack of complex stage machinery, the high-quality libretto and the music of Cesti.

The libretto is by Giacinto Andrea Cicognini . It was first performed in Venice in 1649. The score of this performance has been lost and the libretto does not contain any information about the composer. For a long time it was believed that the music for this production came from Cesti, and accordingly this information is often found in literature as the year of the premiere. However, a letter from the composer Pietro Andrea Ziani to the Venetian impresario Marco Faustini of January 30, 1666 indicates that Francesco Lucio had composed the music. Cesti certainly created the music for the Innsbruck performances in 1656, for which Giovanni Filippo Apolloni revised the libretto and exchanged the prologue. Most of the scores that have survived use this new prologue. The music of Orontea is stylistically more mature than that of his 1651 opera Alessandro vincitor di se stesso.

Other settings of the libretto are by Francesco Cirillo (Naples 1654), Filippo Vismarri (Vienna 1660) and in French by Paolo Lorenzani ( Orontée, Chantilly 1687).

The first performance of Cestis Orontea took place on February 19, 1656 in the Saaltheater Innsbruck . Other Italian performances are for Genoa (1660, 1661), Rome and Florence (1661), Turin (1662), Ferrara (1663), Milan (1664), Macerata (1665), Bologna (1665, 1669), Venice (1666, 1683), Bergamo, Brescia and Palermo (1667), Lucca (1668), Portomaggiore (1670), Naples (1674) and Reggio Emilia (1674). In 1678 Orontea was the first Italian opera to be performed in Hanover. In 1686 the last documented historical production took place in Wolfenbüttel.

Then Orontea was forgotten for several centuries. The score was lost. Only Orontea's aria "Intorno all'idol mio" (second act, scene 17) was included in Charles Burney's A General History of Music from 1789. In the 1950s, three manuscripts of the score were finally made in Italy (Rome, Bibliotheca del Conservatorio Nazionale di Santa Cecilia; Rome, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana; Parma, Bibliotheca del Conservatorio, Bibliotheca Palatina) and another found in Magdalene College in Cambridge. The latter apparently belongs to the Venetian performance of 1666. William Holmes at Wellesley College in 1973 prepared a modern edition based on the Italian manuscripts . Investigations by Jennifer Williams Brown showed that the Cambridge manuscript, contrary to older assumptions, is closer to the lost original version than the Italian manuscripts. Accordingly, the Venetian version from 1666 is based directly on the Innsbruck manuscript from 1656, while the various Italian versions are based on a common model from a later date (Florence 1661 at the latest). For the latter, the original alto parts of Gelone and Alidoro were transposed for bass and tenor, respectively. The versions played in Hanover, Venice 1683 and Wolfenbüttel can also be assigned to the “Cambridge branch”.

More recently, Orontea was not played again until 1961 at the Piccola Scala in Milan. The furnishings and direction came from Vito Frazzi . Bruno Bartoletti was the musical director . It sang u. a. Teresa Berganza (Orontea) and Carlo Cava (Creonte). The first historically informed performance was in Innsbruck in 1982 by René Jacobs . For this purpose, a new version based on the Cambridge manuscript (Venice 1666) was created with some additions from the other manuscripts. From the latter, for example, the prologue (the prologue from Cestis La Doriclea was played in 1666 ), the aria of Orontea in the first scene of the second act and a few additional stanzas of other arias come from. In addition, three of four arias taken from Cestis L'Argia in 1666 were recorded. The overture used was that of Remigio Cestis Il principo generoso (1665) and some instrumental pieces by Cestis and other composers were added.

Recordings

- August 1982 - René Jacobs (conductor).

Andrea Bierbaum (Filosofia), Cettina Cadelo (Amore and Tibrino), Helga Müller-Molinari (Orontea), Gregory Reinhart (Creonte), Guy de Mey (Aristea), René Jacobs (Alidoro), Gastone Sarti (Gelone), David James ( Corindo), Isabelle Poulenard (Silandra), Jill Feldman (Giacinta).

Studio recording based on the Cambridge manuscript.

Harmonia Mundi CD: HMC 901100.02, Harmonia Mundi LP: HM 1100/02. - February / March 2015 - Ivor Bolton (conductor), Frankfurt Opera and Museum Orchestra , Monteverdi Continuo Ensemble.

Katharina Magiera (Filosofia), Juanita Lascarro (Amore and Tibrino), Paula Murrihy (Orontea), Sebastian Geyer (Creonte), Guy de Mey (Aristea), Xavier Sabata (Alidoro), Simon Bailey (Gelone), Matthias Rexroth (Corindo) , Louise Alder (Silandra), Kateryna Kasper (Giacinta).

Live from the Frankfurt Opera .

Oehms OC 965 (3 CD).

literature

- Jennifer Williams Brown: “Innsbruck I have to let you”: Cesti, Orontea, and the Gelone Problem. In: Cambridge Opera Journal , Issue 3, November 2000, JSTOR 3250714 , doi : 10.1017 / S0954586700001798 (currently unavailable) , pp. 179-217.

Web links

- L'Orontea : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Libretto (Italian), Venice 1649. Digital copy from the Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense

- Libretto (Italian), Milan 1662. Digital copy from the Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense

- Libretto (Italian), Wolfenbüttel 1686. Digitized version of the Wolfenbüttel digital library

- Orontea (Antonio Cesti) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- Work information and libretto (Italian) as full text on librettidopera.it

Remarks

- ↑ In the libretto, Paphos (Cyprus) is explicitly stated as the location. Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater and other sources mention Egypt.

- ↑ The part of Aristea is notated in the alto clef.

- ↑ Alidoro is a low tenor or high baritone in the Italian manuscripts; in the Cambridge manuscript it is a "tenore contraltino" (alto key). See the supplement to René Jacobs' record.

- ↑ Gelone is a deep bass in the Italian manuscripts. In the Cambridge manuscript it is a low tenor in the first act and a “tenore contraltino” or alto in the second and third acts.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Jennifer Williams Brown: “Innsbruck, I have to let you”: Tracing Orontea's Footprints. Summary of a talk given April 11, 1997 at Florida State University (PDF), accessed June 1, 2017.

- ↑ a b c d e Wolfgang Osthoff : Orontea. In: Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater . Volume 1: Works. Abbatini - Donizetti. Piper, Munich / Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-492-02411-4 , pp. 526-527.

- ^ A b c d e Carl B. Schmidt: Orontea. In: Grove Music Online (English; subscription required).

- ^ Arnold Feil : Metzler Musik Chronik. JB Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 1993, ISBN 3-476-00929-7 , p. 211.

- ↑ a b c d e f Lorenzo Bianconi: Text accompanying the record HM 1100/02, pp. 16-19.

- ↑ Orontea. In: Harenberg opera guide. 4th edition. Meyers Lexikonverlag, 2003, ISBN 3-411-76107-5 , p. 150.

- ^ A b Reclam's Opernlexikon (= digital library . Volume 52). Philipp Reclam jun. at Directmedia, Berlin 2001, p. 1873.

- ^ Tim Carter: Understanding Italian Opera. Oxford University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-024794-2 , doi : 10.1093 / acprof: oso / 9780190247942.001.0001 , p. 6.

- ^ Silke Leopold : The opera in the 17th century (= manual of musical genres. Volume 11). Laaber, 2004, ISBN 3-89007-134-1 , p. 273.

- ↑ Amanda Holden (Ed.): The Viking Opera Guide. Viking, London / New York 1993, ISBN 0-670-81292-7 , pp. 195-196.

- ↑ Jennifer Williams Brown: “Innsbruck I have to let you”: Cesti, Orontea, and the Gelone Problem. In: Cambridge Opera Journal , Issue 3, November 2000, pp. 202 and 213.

- ^ Ulrich Schreiber : Opera guide for advanced learners. From the beginning to the French Revolution. 2nd Edition. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2000, ISBN 3-7618-0899-2 , p. 75.

- ^ Antonio Cesti. In: Andreas Ommer: Directory of all complete opera recordings (= Zeno.org . Volume 20). Directmedia, Berlin 2005, p. 2679.

- ↑ Supplement to CD Oehms OC 965.