Oxford Castle

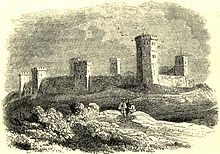

Oxford Castle is a large medieval castle in Norman style on the west side of downtown Oxford in the English county of Oxfordshire . Today the castle is partially derelict. Most of the wooden motte , originally surrounded by a moat , was replaced by a stone structure in the 11th century, which played an important role in the anarchy . In the 14th century, the castle's military importance declined and Oxford Castle served mainly as an administrative building and prison.

In the English Civil War , most of the castle from the 11th century was destroyed in the 18th century, the remaining buildings to Oxford city jail were. From 1785 a new prison complex was built on the site, which was expanded again in 1876. This then became HM Prison Oxford.

The prison was closed in 1996 and the building was converted into a Malmaison chain hotel . The medieval remains of the castle, the motte, St. George's Tower and the crypt have been listed as Grade I Historic Buildings by English Heritage and are a Scheduled Monument .

history

construction

According to the Abingdon Church Chronicle, Oxford Castle was built between 1071-1073 at the behest of the Norman Baron Robert D'Oyly . D'Oyly arrived in England with William the Conqueror during the Norman conquest of England in 1066. The king gave him extensive lands in Oxfordshire as a fief. The city of Oxford was overrun during the conquest and badly damaged. King William ordered D'Oyly to have a castle built to rule the city. Subsequently, D'Oyly became the largest landowner in Oxfordshire and received the hereditary office of constable for Oxford Castle. Oxford Castle is not one of the 48 castles mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086, but not all castles in existence at the time were listed there.

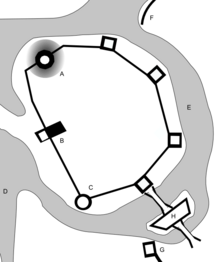

D'Oyly had his castle built on the west side of the city, using an arm of the Thames as protection for the side of the castle facing away from the city. Today this Arm is called Castle Mill Stream . He had his arm split so that it could be used as a moat. There is debate about whether there was an earlier English castle at this point. Evidence of an earlier Anglo-Saxon settlement was found there, but it does not allow any conclusions to be drawn about a fortress. Oxford Castle was clearly an "urban castle", but it could not be determined whether existing buildings there had to be demolished to make way for the castle. The Domesday Book does not record any demolition of buildings, so the site may have been empty from the destruction caused by the Norman occupation of the city. On the other hand, it is also possible that the castle was built along an existing street, which would only have been possible after several houses had been demolished.

The first castle was probably a large moth on the same floor plan that D'Oyly had built 7.5 km away in Wallingford . The moth was originally about 18 meters high and 12 meters wide, built with walls made of layers of pebbles that were glued and covered with clay. There were discussions about whether the moth or the castle wall came into being first. The latter would have made the first castle more like a ring work (without a moth).

In the middle of the 12th century, stone-built Oxford Castle was substantially expanded. The first building created in this way is St. George's Tower , which was built from coral limestone in 1074, has a base of 9 meters × 9 meters and, for reasons of stability, is significantly narrower towards the top. This was the tallest of the castle towers, perhaps because it protected the entrance to the old west gate of the city.

Within its walls, the tower housed a chapel in a crypt, where a church may previously have stood. This crypt chapel originally had a nave, a pulpit and an apse. It is built in a typical Norman style with solid pillars and arches. In 1074 D'Oyly and his best friend, Roger d'Ivry , furnished the chapel with a college of priests. Initially the chapel was dedicated to St. George .

In the early 13th century, the wooden keep at the highest point of the Motte was replaced by a ten-sided, stone keep, 17.4 meters high, very similar to those of Tonbridge Castle and Arundel Castle . The donjon enclosed a number of buildings so that the remaining courtyard was only 6.6 meters diagonal. In the donjon a staircase led 6 meters down to a 3.6 meter wide room with a Gothic, hexagonal vault and a 16 meter deep well, from which water could be drawn during a siege.

The role of the castle during the anarchy and the war of the barons

Robert D'Oyly the Younger , nephew of Robert D'Oyly the Elder, inherited the castle from his uncle in the 1140s, during the anarchy . After initially supporting King Stephen , he later swore his allegiance to Empress Matilda , Stephen's cousin and rival for the throne. In 1141 the Empress marched to Oxford and made the castle her battle base. Stephan responded by unexpectedly leaving Bristol in December , attacking and taking the city of Oxford, and besieging the castle with Matilda. Stephan set up two earth walls called "Jew's Mount" and "Mount Pelham" next to the castle, on which he had siege engines built - mostly for show purposes. So he continued the siege and waited for Matilda and the garrison to gradually run out of supplies over the next three months. Stephan himself had difficulties in supplying his troops in the winter and so his decision is a sign of the apparent strength of Oxford Castle at the time.

Matilda responded by fleeing the castle; Legend has it that she waited until Castle Mill Stream had frozen over, then dressed in white to be camouflaged in the snow, rappeled over the walls with three or four knights, and finally escaped through the night Stephen's lines while the king's guards tried to sound the alarm. The chronicler William of Malmesbury says, however, that Matilda did not let herself down over the walls, but escaped through one of the gates. Matilda reached Abingdon-on-Thames safely and the garrison of Oxford Castle surrendered to Stephen's troops the next day. Robert D'Oyly had died in the final weeks of the siege and the castle was given to Wilhelm de Chesney for the remainder of the war. At the end of the war, the post of constable was given to Roger de Bussy before it was claimed in 1154 by Henry D'Oyly , Robert's younger son.

In the first war of the barons 1215-1217 the castle was attacked again, which led to further improvements to the fortifications. In 1220, Falkes de Bréauté , who controlled many castles in Central England, had the church of St. Budoc in the south-east of the castle demolished and a barbican with a moat built in order to be able to better defend the main entrance to the castle. The remaining wooden buildings were replaced by stone buildings. In this context, the Round Tower was built in 1235 . King Henry III had part of the castle converted into a prison, in particular to imprison university employees who caused difficulties. He also had the castle chapel renovated, replacing the old, barred windows with stained glass in 1243 and 1246. As Beaumont Palace was north of Oxford , Oxford Castle never became a royal residence.

14th to 17th centuries

By 1327 the fortifications of the castle, particularly the gates and barbican, were in severe disrepair and repairs were estimated at £ 800. From the 1350s the castle had little military value and was left to deteriorate further. It became an administrative center for the county of Oxfordshire, a prison and a criminal court. Jury trials were held there until 1577. In that year the plague broke out there , which became known as the "black jury trial": the Lord Lieutenant of Oxfordshire, two knights, 80 gentlemen and the entire grand jury of this trial fell victim to him, including Sir Robert D'Oyly , a relative of the builder of the castle. After that, the holding of jury trials in the castle was given up.

In the 16th century the barbican was demolished to make way for residential houses, and new houses were also built in the moat. In 1600 the moat was almost completely silted up and houses had been built around the castle wall. In 1611 King James I sold Oxford Castle to James and Robert Younglove , who in turn resold it to Christ Church College in 1613 . The college leased the property to various local families in the years that followed. At that time Oxford Castle was in a desolate condition, a wide crack ran down the side of the donjon.

In 1642 the English Civil War broke out and the royalists made Oxford their capital. Roundhead troops successfully besieged Oxford in 1646 and the city was occupied by Colonel Ingoldsby . Ingoldsby left the fortifications of the castle expand, but not that of the surrounding city, and in 1649 he made the most medieval walls destroy them by more modern earth bastions replace and reinforce the Donjon with Erdbastionen so he could serve as a platform for cannons. In 1652, during the Third English Civil War, the parliamentary garrison responded to the proximity of King Charles II's troops by demolishing the fortifications and retreating to New College , causing great destruction in the college. In the course of this conflict there was no further fighting in Oxford. At the beginning of the 18th century, the donjon was demolished and the highest point of the motte was designed in the shape it is today.

Role as a prison

After the Civil War, Oxford Castle was primarily used as a city prison. As with other prisons at the time, the owner, in this case Christ Church College , leased the castle to overseers who made their profit by making inmates pay for their boarding and lodging. The prison also had a gallows to execute prisoners such as B. Mary Blandy 1752. For most of the 18th century, the prison was operated by the local Etty and Wisdom families and deteriorated. In the 1770s, prison reformer John Howard visited the castle several times and criticized its size and condition, e.g. B. the extent to which vermin infested the prison. Partly because of this criticism, those responsible de Grafschaft decided to have a new city prison built.

In 1785 the Oxfordshire County Justice Department bought Oxford Castle and construction of the prison began under the London architect William Blackburn . The wider perimeter of the castle changed at the end of the 18th century with the construction of the New Road through the courtyard and the complete filling of the moat to build the new end of the Oxford Canal . The construction of the new prison went hand in hand with the demolition of the old college, which was attached to the St. George's Chapel, and the relocation of the crypt in 1794. The work was completed in 1805 under Daniel Harris . Harris was paid decently as the new governor and had prisoners carry out the first archaeological excavations at the castle under the direction of the historian Edward King .

In the 19th century, various new buildings were built on the site, e.g. B. the new County Hall 1840-1841 and the arsenal of the Oxfordshire Militia in 1854. The prison was expanded in 1876, which then occupied most of the remaining space in the courtyard. In 1888 national prison reforms led to the city prison being renamed HM Prison Oxford .

today

Since 1954, English Heritage has had the two oldest parts of the castle, the 11th century Motte with the 13th century fountain and the 11th century St. George's Tower with its crypt chapel, the 18th century D-wing. Century and the debt tower are listed as historical building of the first degree. The property is protected as a Scheduled Monument .

The prison closed in 1996 and the property returned to Oxfordshire County Council . The buildings of Oxford Prison have since been converted into a restaurant, a historic complex with guided tours and open courtyards for markets and theater performances. This complex also includes a Malmaison chain hotel in much of the former prison blocks, with former cells being converted into guest rooms. The parts of the prison where corporal or death sentences were carried out have been converted into offices. The mixed-use development project, which officially opened on May 5, 2006, was voted RICS Project of the Year in 2007.

Individual evidence

- ↑ CG Harfield: A hand-list of Castles Recorded in the Domesday Book in English Historical Review . No. 106 (1991). P. 388.

- ↑ a b c T. Joy: Oxford Delineated: A sketch of the history and antiquities . Whessell & Bartlett, Oxford 1831. p. 28. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d James Dixon McKenzie: The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure . Books LLC, Memphis 1896/2009. ISBN 978-1-150-51044-1 . P. 147.

- ^ A b Geoffrey Tyack: Oxford: an Architectural Guide . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1998. ISBN 978-0-19-817423-3 . P. 5.

- ^ Emilie Amt: The Accession of Henry II in England: Royal Government Restored, 1149-1159 . Boydell Press, Woodbridge 1993. ISBN 978-0-85115-348-3 . Pp. 47-48.

- ↑ CG Harfield: A hand-list of Castles Recorded in the Domesday Book in English Historical Review . No. 106 (1991). Pp. 384, 388-389.

- ^ EM Jope: Late Saxon Pits Under Oxford Castle Mound: Excavations in 1952 in Oxoniensia . Booklet XVII-XVIII (1952–1953). P. 79.

- ^ OH Creighton: Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England . Equinox, London 2002. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8 . P. 146.

- ^ OH Creighton: Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England . Equinox, London 2002. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8 . P. 148.

- ^ TG Hassall: Excavations at Oxford in Oxoniensia . Booklet XXXVI (1971). P. 2.

- ^ Geoffrey Tyack: Oxford: an Architectural Guide . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1998. ISBN 978-0-19-817423-3 . P. 6, 80.

- ^ A b James Dixon McKenzie: The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure . Books LLC, Memphis 1896/2009. ISBN 978-1-150-51044-1 . P. 148.

- ^ A b c Geoffrey Tyack: Oxford: an Architectural Guide . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1998. ISBN 978-0-19-817423-3 . P. 6.

- ^ A b c T. G. Hassall: Excavations at Oxford Castle: 1965-1973 in Oxoniensia . Booklet XLI (1976). P. 233.

- ^ A b Geoffrey Tyack: Oxford: an Architectural Guide . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1998. ISBN 978-0-19-817423-3 . P. 7.

- ^ A b c d e Geoffrey Tyack: Oxford: an Architectural Guide . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1998. ISBN 978-0-19-817423-3 . P. 8.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j James Dixon McKenzie: The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure . Books LLC, Memphis 1896/2009. ISBN 978-1-150-51044-1 . P. 149.

- ^ A b Christopher Gravett, Adam Hook: Norman Stone Castles: The British Isles, 1066-1216 . Osprey, Botley 2003. ISBN 978-1-84176-602-7 . P. 43.

- ^ A b Emilie Amt: The Accession of Henry II in England: Royal Government Restored, 1149-1159 . Boydell Press, Woodbridge 1993. ISBN 978-0-85115-348-3 . P. 48.

- ^ A b c d Christopher Gravett, Adam Hook: Norman Stone Castles: The British Isles, 1066-1216 . Osprey, Botley 2003. ISBN 978-1-84176-602-7 . P. 44.

- ^ Emilie Amt: The Accession of Henry II in England: Royal Government Restored, 1149-1159 . Boydell Press, Woodbridge 1993. ISBN 978-0-85115-348-3 . Pp. 56-57.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h T. G. Hassall: Excavations at Oxford Castle: 1965-1973 in Oxoniensia . Booklet XLI (1976). P. 235.

- ^ TG Hassall: Excavations at Oxford in Oxoniensia . Booklet XXXVI (1971). P. 9.

- ↑ a b Mark Davies: Stories of Oxford Castle: From Dungeon to Doughill . Oxford Towpath Press, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-9535593-3-5 . P. 3.

- ^ Richard Marks: Stained glass in England during the Middle Ages . Routledge, London 1993. ISBN 978-0-415-03345-9 . P. 93.

- ↑ Julian Munby: Malchair and the Oxford topographical tradition in Colin Harrison (Editor): John Malchair of Oxford: Artist and Musician. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 1998. ISBN 978-1-85444-112-6 . P. 96.

- ^ Alan Crossley, C. Elrington (Editor): A History of the County of Oxford . Volume 4: The City of Oxford . Victoria County History, 1979. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ↑ a b Mark Davies: Stories of Oxford Castle: From Dungeon to Doughill . Oxford Towpath Press, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-9535593-3-5 . Pp. 91-92.

- ^ TG Hassall: Excavations at Oxford Castle: 1965-1973 in Oxoniensia . Booklet XLI (1976). Pp. 235, 254.

- ↑ a b c Oxford Archeology . Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ↑ a b c T. Joy: Oxford Delineated: A sketch of the history and antiquities . Whessell & Bartlett, Oxford 1831. p. 29. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ↑ a b Mark Davies: Stories of Oxford Castle: From Dungeon to Doughill . Oxford Towpath Press, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-9535593-3-5 . P. 6.

- ↑ Mark Davies: Stories of Oxford Castle: From Dungeon to Doughill . Oxford Towpath Press, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-9535593-3-5 . P. 106.

- ↑ Mark Davies: Stories of Oxford Castle: From Dungeon to Doughill . Oxford Towpath Press, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-9535593-3-5 . Pp. 9-10.

- ↑ Mark Davies: Stories of Oxford Castle: From Dungeon to Doughill . Oxford Towpath Press, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-9535593-3-5 . P. 14.

- ↑ Mark Davies: Stories of Oxford Castle: From Dungeon to Doughill . Oxford Towpath Press, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-9535593-3-5 . P. 15.

- ^ A b R. C. Whiting, RC (1993) Oxford: Studies in the History of a University Town Since 1800 . Manchester University Press, Manchester 1993. ISBN 978-0-7190-3057-4 . P. 54.

- ^ A b St George's Tower, St George's Chapel, Crypt and D Wing, including the Debtor's Tower . Historic England . Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ↑ Julian Munby: Malchair and the Oxford topographical tradition in Colin Harrison (Editor): John Malchair of Oxford: Artist and Musician. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 1998. ISBN 978-1-85444-112-6 . P. 53.

- ↑ Mark Davies: Stories of Oxford Castle: From Dungeon to Doughill . Oxford Towpath Press, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-9535593-3-5 . P. 24.

- ↑ Well House, Oxford Castle . English Heritage . Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Oxford Castle . Gatehouse Gazetteer. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Philip Smith: Punishment and Culture. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2008. ISBN 978-0-226-76610-2 , p. 93.

- ↑ RICS Awards 2007 Winners list: RICS project of the year: Winner: Oxford Castle Heritage Project, Oxford, South East UK . RICS, October 19, 2007. ( Memento of October 23, 2007 on the Internet Archive ) Retrieved June 18, 2015.

Web links

- Official website of Oxford Castle

- Oxford Castle . Gatehouse Gazetteer.

- Oxford Castle Unlocked website

- Website of the Malmaison Hotel Oxford

Coordinates: 51 ° 45 ′ 11.2 " N , 1 ° 15 ′ 50.4" W.