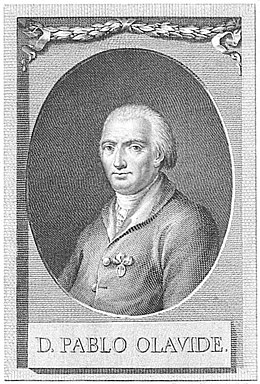

Pablo de Olavide

Pablo Antonio José de Olavide y Jáuregui (born January 25, 1725 Lima ( Peru ), † February 25, 1803 Baeza ( Jaén )) was a Hispanic American lawyer , politician, translator , author and educator .

Live and act

His life in the viceroyalty of Peru

He was born as the only son of the merchant Martín José de Olavide y Albizu (1686–1763) from Lácar in Alta Navarra and his first wife, María Ana Teresa de Jáuregui Ormaechea y Aguirre (* 1705) in the Viceroyalty of Peru . The parents had both been married since 1724. His second wife named Doña María de Lezaún - Martín José de Olavide married her in 1736 - gave Pablo de Olavide two younger siblings: Gracia Estefanía de Olavide (1744–1775) and Pedro Esteban de Olavide Lezaún (1741–1776). His sister died in Baeza in 1775.

De Olavide studied at the of Jesuit -run Colegio Real de San Martín de Lima and Universidad de San Marcos de Lima the subjects theology and jurisprudence . In 1740 he graduated here in canon law and two years later in 1742 in secular law.

In 1741 he was admitted to the bar, Audiencia at the Supreme Court, Real Audiencia in Lima, Audiencia y Cancillería Real de Lima and appointed as an assessor at the Commercial Court, Consulado . As early as 1745 he got the position of an oidor .

After the earthquake that destroyed Lima on October 28, 1746, Viceroy José Antonio Manso de Velasco appointed him administrator of the victims' estate, but in this capacity he was accused of having used the assets to build a theater to have. The Consejo de Indias charged him with these charges in 1750. He then fled to Spain to avoid further problems with the law.

His time in motherland Spain

De Olavide was a personal friend of the from 1766 to 1773 in the function of a Minister of King Charles III. Royal in the Supreme Council of Castile, Real y Supremo Consejo de Castilla make Pedro Pablo Abarca de Bolea (1719-1798). The Spanish Crown commissioned de Olavide to reform the University of Seville.

When he arrived in Spain in 1752, he was soon made Knight of the Order of Santiago . In 1765 he moved to Madrid and founded a literary salon based on the French model. Even Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes wrong here. A close confidante in Madrid was Don Miguel de Gijón y León . Also through the relationships between de Campomanes and Pedro Pablo Abarca de Bolea, conde de Aranda , de Olavide was appointed to other higher offices in the Spanish monarchy, which was striving for reforms.

In connection with these reform efforts by the Spanish crown, he was appointed assistant to the mayor of Seville, Asistente de Sevilla , and also provincial director of the Army of the Four Kingdoms of Andalusia, Intendente del Ejército de los cuatro reinos de for the period from 1767 to 1778 Andalucía (Jaen, Cordoba, Granada and Seville). In 1754, at the request of the public prosecutor in Lima, he was briefly detained on charges of corruption in the performance of his duties. He was released on bail . In 1757 the process was closed after he had given up all of his public offices in the colonies.

Meanwhile, in 1755, he married a wealthy widow named Isabel de los Ríos. Both traveled from 1757 to 1765 on at least three major trips through Italy and especially France, where they finally lived for eight years. He became an afrancesado an enthusiast of the French Philosophes . He was friends not only with Voltaire , but also with Denis Diderot . He stayed with Voltaire for a short time at his country estate in his castle Les délices in Ferney near Lake Geneva. In Madrid he is said to have often visited relevant tertulias .

Charles III tried to develop different regions of southern Spain, especially Andalusia . As Superintendente de las Nuevas Poblaciones de Sierra Morena y Andalucía, De Olavide headed the colonization in the Sierra Morena in northern Andalusia. Under his organizational direction, more than forty new settlements were built in just a few years, some of which were also foreign immigrants, including from regions of what is now Rhineland-Palatinate and the southwest of the Holy Roman Empire , see also Johann Kaspar Thürriegel . The spiritual leadership of the German-speaking settlers was a group of Capuchins. As a late consequence of the Reconquista , large stretches of land were only very sparsely populated. But this was definitely in the interests of the Mesta . Because the large estates ( latifundia ) were often owned by the church and high nobility. These landowners, Honrado Concejo de la Mesta, saw migratory sheep breeding as an excellent way to use the pastureland and to make economic profit. When the Mesta lost this privilege, de Olavide was supposed to settle farmers there. He succeeded with great success and so cities and settlements emerged with a liberal constitution he initiated. In addition, on April 2, 1767 by a decree of Charles III. the Societas Jesu ( Jesuits ) were expelled from Spain. From 1769 the property of the Jesuits was auctioned for the benefit of the Spanish crown.

In his new position, De Olavide planned to implement various reforms based on the ideas of an "enlightened despotism", Despotismo Ilustrado . In his text Informe sobre la ley agraria ( 1768 ) on agrarian reform, he took a physiocratic view. His reform plans found opposition not only on the most varied levels of the royal bureaucracy, other agencies such as church authorities or the local power apparatus also had to be convinced. An undertaking which de Olavide only succeeded in thanks to powerful and influential patrons at the Spanish court in Madrid. With the appointment of Pedro Pablo de Aranda as future ambassador of Spain in Paris in 1773, one of the main pillars of de Olavide's endeavors broke away.

His critical attitude towards the Church and his publications increasingly brought him into conflict with the Spanish Inquisition . Officially since 1775 the Holy Inquisition has been collecting suspicions and evidence against de Olavide. From this date onwards, by authorization from Charles III. opened formal proceedings for heresy and free spirit. The decisive factor for the inquisition process, however, were ultimately the accusations of a German Capuchin who had come to Nuevas Poblaciones de Andalucía with the colonists . So he was accused of godlessness and heresy by the Inquisition in 1775 . In the indictment, a total of one hundred and forty-six points were listed, for example he is said to have denied the concept of miracle and mocked the veneration of saints , and he had doubted the salvific value of the works of mercy , the existence of hell and original sin . He also advocated a more tolerant approach to Protestants . He was removed from his offices, made to wear the Sanbenito , and de Olavide was imprisoned in custody in 1776. The verdict, passed in 1778, consisted of eight years of forced residency in the solitude of various Spanish monasteries. At first de Olavide was housed in the Monasterio leonés de Sahagún . There he was forced to read religious books under supervision.

Due to the intercession of the Grand Inquisitor Felipe Beltrán Serrano , de Olavide was allowed to leave one of the monasteries for a bath because of his health restrictions. In 1780, during one of his stays in Caldes de Malavella , a Catalan town, de Olavide fled to France and on to Geneva. De Olavide stayed in Geneva until a possible Spanish extradition request to which the French monarchy had been rejected. From 1781 he stayed in Paris. In the French capital he got to know many of the Philosophes , including Denis Diderot . He took his encounters with de Olavide as an opportunity to put down a biography of a representative of the Spanish Enlightenment in the Correspondance littéraire, philosophique et critique .

Stay in France

In France he was greeted by his friends Voltaire and Diderot. He lived in Toulouse , Geneva and Paris . However, in order to avoid extradition, De Olavide hid his identity under the pseudonym Conde de Pilos . He took part in the political changes during the French Revolution from 1789 to 1799. By the mountain party , La Montagne , he got into great distress during the reign of terror , la Terreur . During the terror, he retired to the Château de Meung-sur-Loire in the village of Meung-sur-Loire in 1791 . But de Olavide was arrested by the security committee , Comité de sûreté générale on the night of April 16, 1794 and sentenced to prison in Orléans . After the 9th Thermidor , he left France and returned to Spain, having anonymously published a retraction of his “mistakes and aberrations” in the triumph of the Gospel, El Evangelio en triunfo o historia de un filósofo desengañado (1797) in Valencia had brought.

Back in Spain

De Olavide was able to publish some of his stories in Madrid in 1800 under the pseudonym Atanasio de Céspedes y Monroy . He established connections to the Spanish crown under Charles IV in order to make a repatriation to his home country possible. Finally, in 1798, he was received by Manuel de Godoy in Spain. He was also granted an annual pension of 90,000 reals .

Until his death he lived in Baeza, which is also where his grave can be found. His remains are in the crypt of the Iglesia de San Pablo (Baeza) .

Honors

The University of Pablo de Olavide (UPO) was only founded in 1997, making it one of the youngest public universities in Spain. It was named after his name in honor of Pablo de Olavide. The Society La Fundación de Municipios Pablo de Olavide awards a prize for work on topics with educational thoughts; Premio de Ensayo Pablo de Olavide: el Espíritu de la Ilustración .

Works (selection)

Poetry

- Poemas christianos en que se exponen con sencillez las verdades más importantes de la religón, Madrid: Joseph Doblado, 1799

Theatrical works

- El desertor. Edic. de Trinidad Barrerar y Piedad Bolaños. Seville: Ayto. Seville, 1987. Translation by Louis Sebastian Mercier.

- Hipermnestra. Translation by Antoine Marin Lemierre.

- Lina. Translation by de Lemierre.

- El jugador. Translation by de Jean François Regnard.

- Mitrídates. Barcelona, Imp. De Gilbert y Tutó, no year, translation by de Racine.

- Celmira. Translated by de Dormont du Belloy.

- Zayda. Translation by de Voltaire.

- Casandro y Olimpia. Translation by de Voltaire.

Zarzuelas

- El celoso burlado. 1764, inspirada en El celoso extremeño de Cervantes pero traducida al parecer del italiano.

Studies, essays

- Informe sobre el proyecto de colonización de Puerto Rico y America del Sur 1927

- Informe sobre el proyecto de colonización de Sierra Morena. Publicado también por el profesor Cayetano Alcázar Molina in 1927.

- Hermandades y Cofradías de Seville.

- Informe sobre la ley agraria. 1768.

- Plan de estudios para la Universidad de Seville. Ediciones Cultura Popular, Barcelona 1969.

stories

- Teresa o el terremoto de Lima. Imprenta de Pillet, Paris 1829.

- El Evangelio en triumpho o Historia de un filósofo desengañado. Imprenta de Joseph de Orga, Valencia 1797, muy reimpresa (alcanzó dieciocho ediciones en poco tiempo). Hay edición moderna (Oviedo: Fundación Gustavo Bueno, 2004) en dos volúmenes al cuidado de José Luis Gómez Urdáñez sobre el texto de la sexta edición, Madrid: José Doblado, 1800, 4 vols.

- The incógnito or the fruto de la ambición.

- Paulina o el amor desinteresado.

- Sabina o los grandes sin disfraz. (PDF; 1.1 MB)

- Marcelo o los peligros de la corte.

- Lucía o la aldeana virtuosa.

- Laura o el sol de Seville.

- El estudiante o el fruto de la honradez.

literature

- Francisco Aguilar Piñal: La Sevilla de Olavide, 1767–1778. Ayuntamiento de Sevilla, Séville 1995, ISBN 84-86810-60-4 .

- María José Alonso Seoane: La obra narrativa de Pablo de Olavide: nuevo planteamiento para su estudio. In: Axerquía. num. 11, 1984, pp. 11-49.

- Marcelin Defourneaux: Pablo de Olavide ou l'Afrancesado (1725-1803). Paris 1959.

- Marcelin Defourneaux: Pablo de Olavide: l'Homme et le Mythe. In: Cahiers du monde hispanique et luso-brésilien. Volume 7, Numéro 7, 1966, pp. 167-178.

- J. Huerta, E. Peral, H. Urzaiz: Teatro español de la A a la Z. Espasa-Calpe, Madrid 2005.

- Juan Marchena Fernández: El tiempo ilustrado de Pablo de Olavide: vida, obra y sueños de un americano en la España del s. XVIII. (contient le Program de Réformes pour l'Université de Séville réalisé par Pablo de Olavide), Alfar, Séville 2001, ISBN 84-7898-180-2 .

- Luis Perdices de Blas: Pablo de Olavide (1725-1803). El Ilustrado. Editorial Complutense, Madrid 1995, ISBN 84-7898-180-2 .

- J. Perez: Histoire de l'Espagne. Fayard, Paris 1996.

- Christian von Tschilschke : Identity of the Enlightenment / Enlightenment of the Identity. Vervuert Verlagsges., 2009, ISBN 978-3-86527-437-3 .

- Martin Fontius: Enlightenment Germany and Spain. Volume 7. III In The Scientific Work. de Gruyter 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-014547-2 .

- Florian Dittmar: The (German-born) internal colonization of the Sierra Morena and Lower Andalusia in the 18th century: planning, implementation and persistent structures around La Carolina and La Carlota [German colonies abroad]. Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt, thesis, 2004.

- Klaus-Dieter Ertler: A short history of the Spanish educational literature. (= Fool study books ). Narr Francke Attempto, Tübingen 2003, ISBN 3-8233-4997-X .

Web links

Wikisource. Obras originales de Pablo de Olavide

- La Fundación de Municipios Pablo de Olavide

- Universidad de Seville. Biographical data in Spanish

- Pablo de Olavide (PDF; 140.82 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Allan J. Kuethe: Pablo de Olavide: El espacio de la reforma ilustracion y la universitaria. In: Hispanic American Historical Review. Volume 82, No. 2, May 2002, pp. 368-370.

- ↑ Family genealogy

- ↑ martes, 27 de enero de 2009. Pablo de Olavide y su obra narrativa. BIOGRAPHY

- ↑ Biography of the sister

- ↑ Marcelin Défourneaux: Pablo de Olavide et sa famille (A propos d'une Ode de Jovellanos). In: Bulletin Hispanique Année. Volume 56, Numéro 56-3, 1954, pp. 249-259. (PDF; 843.79 kB)

- ↑ Helmut Reinalter (Ed.): Lexicon on Enlightened Absolutism in Europe. Böhlau-Verlag, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2005, ISBN 3-8252-8316-X , pp. 450–453.

- ↑ Elmar Mittler, Ulrich Mücke (Ed.): The Spanish Enlightenment in Germany. An exhibition from the holdings of the Lower Saxony State and University Library. (= Göttingen Göttingen library publications. 33). Göttingen 2005, p. 75. (PDF; 758 kB)

- ↑ Miguel de Jijon y León. diccionariobiograficoecuador.com. Detailed biography in Spanish

- ↑ Emigration all over the world - Spain - The emigrants in Spain. 6: The reception of the emigrants at the places of arrival. ( Memento from December 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ "Annual reports for German history" from the interwar period (Vol. 1-14, reporting years 1925–1938)

- ↑ Biography of Pablo de Olavide

- ↑ Friedrich Melchior Freiherr von Grimm, Denis Diderot, Jacques-Henri Meister, Jules Antoine Taschereau, A. Chaudé: Correspondance littéraire, philosophique et critique de Grimm et de Diderot, depuis 1753 jusqu'en 1790. Volume 11, Furne, 1830, p 240.

- ↑ Walter Jens (ed.): Kindlers new literary dictionary. Kindler Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-463-43020-7 , p. 43. (PDF; 3.9 MB)

- ↑ Henry Charles Lea: History of the Spanish Inquisition. First volume, Europäische Geschichtsverlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-86382-735-9 , p. 573: For comparison: In the 18th century, an average daily worker in a mint received a daily wage of 3.5 copper reals, while a foreman there earned 6 Real.

- ↑ Presentation of the UPO by the Rector ( Memento of the original of February 21, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Olavide, Pablo de |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Pablo Antonio José de Olavide y Jáuregui; Conde de Pilos (pseudonym); Atanasio de Céspedes y Monroy (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Hispanic American lawyer, author, and politician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 25, 1725 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Lima |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 25, 1803 |

| Place of death | Baeza |