Padma Bridge

Coordinates: 23 ° 25 ′ 21 ″ N , 90 ° 18 ′ 35 ″ E

| Padma Bridge পদ্মা সেতু |

||

|---|---|---|

| Padma Bridge under construction | ||

| use | Road and rail bridge | |

| Crossing of | Lower Padma | |

| place | between Zajira ( Shariatpur District ) and Mawa ( Munshiganj District ) in Bangladesh | |

| Entertained by | Bangladesh Bridge Authority | |

| construction | Steel truss bridge with concrete ceiling | |

| overall length | 6.15 km | |

| width | 20.65 m (deck girder) | |

| Longest span | 150 m | |

| Pillar strength | 3.0 m | |

| building-costs | projected: US $ 3.7 (with adjacent infrastructure and river engineering) | |

| start of building | Oct. 2013 (access roads) Dec. 12, 2015 (actual bridge) |

|

| completion | possibly 2021 | |

| opening | not yet fixed | |

| construction time | so far 6 years | |

| planner | AECOM | |

| toll | Yes | |

| location | ||

|

|

||

The Padma Bridge ( Bengali পদ্মা সেতু ) is a 6.15-kilometer-long combined road and rail bridge under construction over the Padma River in Bangladesh . Completion was originally planned for November 2018. However, this has been delayed and commissioning is now expected in 2021. It is the largest infrastructure project in the country's history to date. When completed, the Padma Bridge will be the largest bridge in Bangladesh and the longest bridge in South Asia .

background

Bangladesh is divided into three parts of the country by the two great rivers Padma (the continuation of the Ganges , called Meghna in the end section ) and Jamuna (see adjacent map). First, the region north of the Padma and east of the Jamuna, second, the region south of the Padma and third, the region west of Jamuna and north of the Padma. The agglomerations around the two largest cities Dhaka and Chittagong are the most developed economically , while other regions show significantly poorer economic and socio-economic indicators. Economic development is also hampered by the fact that there are only a few bridges between these three parts of the country. There are only two bridges over the Padma in the far west of the country: the Hardinge Railway Bridge , built in British colonial times at the beginning of the 20th century, and the Lalon-Shah Road Bridge , which was built parallel to it and opened in 2004 . There is currently no bridge further downstream. The inadequate road and rail infrastructure and the lack of bridge structures are also the reason why there are so many regional airports in Bangladesh - a relatively small country in terms of area . Apart from air traffic, the entire transport of goods and people between the capital region of Dhaka and the south-west of the country has so far only been handled by ferries .

For a long time there were considerations to build a bridge in the lower reaches of the Padma. In the past, given the large dimensions of the several kilometers wide river, which changed its riverbed several times in the past, such a project did not seem feasible. Encouraged to a certain extent by the success of other large bridge projects ( Bangabandhu Bridge 1998, Lalon Shah Bridge 2004), there were several feasibility studies for the construction of a Padma Bridge from 2000 onwards . These feasibility studies dealt with the question of the optimal location of a bridge (taking into account local flow conditions, bank erosion and geological conditions), with traffic forecasts and with the basic bridge design. The first drafts were for roadway girders made of concrete elements and a cable-stayed bridge with a maximum span of 180 meters. This plan was ultimately changed to a steel truss bridge with a maximum span of 150 meters, which should have a lower deck with a single-lane railway line and an upper deck with a four-lane road, due to the forecast increased traffic loads .

Technical specifications

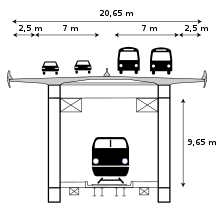

The Padma Bridge is designed as a steel truss bridge and a combined single-lane railway and four-lane road bridge. The railway line is to be on the lower deck, flanked by two sidewalks, and the four-lane concrete road surface on the upper deck. At both ends of the bridge there are 720 m to 875 m long driveways, each with a span of 38 m. The railway viaducts are 2.36 km and 2.96 km long and also have spans of 38 m. The 41 steel lattice girders of the actual bridge, with a span of 150 m, rest on 42 concrete platforms. The concrete platforms in turn rest on a total of 262 steel pillars that are driven deep into the ground, analogous to the construction principle of the Bangabandhu Bridge . The width of the carriageway girder is 20.65 m, which includes the two 7 m wide double lanes. The railway line is designed as a single-lane three- rail track so that it can be used by broad-gauge and meter- gauge trains. The clearance under the bridge should be 18.30 m.

building-costs

The first draft in 2004 predicted construction costs of US $ 1.26 billion. After corresponding changes in the bridge design and, in particular, greater consideration of river engineering measures, the costs in 2009 were estimated at US $ 1.904 billion. Before construction began, the cost estimates had risen to US $ 2.418 billion. On January 6, 2016, the Bangladeshi government increased the estimated construction cost to 28,793 crore taka (about US $ 3.7 billion). The increase in costs was justified with additional river engineering measures and additional expansion work at both ends of the bridge. This was offset by an estimated economic benefit of approximately US $ 5.942 billion. It is estimated that the completed bridge could increase the economic growth rate of all of Bangladesh by around 1% annually.

Building history

Original construction and financing plan

The original schedule called for a bridge to be built from 2011 to August 31, 2016. The total costs estimated at that time of US $ 2.915 billion were divided into 1.626 billion for the actual bridge with access roads, 799.9 million for river engineering measures, 291.9 million for social measures (compensation for the resettled population) and environmental measures, and a further 98 million other costs .

Funding should come from the International Development Organization (IDA), a subsidiary of the World Bank Group (US $ 1.2 billion loan), the Asian Development Bank (ADB, 76 million loan and 539 million loan), the Japanese Agency for International Cooperation (JICA , 400 million) and the Islamic Development Bank (140 million). The remaining amount should be raised by the Bangladeshi government.

By April 2019, the costs had almost quadrupled from the originally estimated 101.61 billion Taka to 392.58 billion Taka.

Corruption allegations

In the run-up to the start of the project, allegations of corruption were raised. The World Bank called for official investigations and the removal of persons accused of corruption and finally officially withdrew from funding the project on June 29, 2012. In February 2013, the ADB, JICA and IDB followed with analogous steps. With the withdrawal of donors, the realization of the project was seriously called into question. However, the Bangladeshi government announced that it would not give up the project, but would instead finance it from its own resources.

In a statement on January 17, 2016, Prime Minister Hasina Wajed described her point of view. According to this, the financing by the World Bank was stopped at the instigation of "a specific person". Hasina did not give a name, but it became clear from the context that she meant Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus . Yunus was removed from his position as managing director of Grameen Bank in 2011 by the Bangladesh Bank . The reason given was that the retirement age was exceeded by 10 years. Yunus had challenged this decision in court, but was unsuccessful. In a kind of act of revenge, the Prime Minister then ensured that the financing by the World Bank was stopped. Her entire cabinet, as well as her family, according to Hasina Wajid, were unjustifiably inundated with corruption allegations before any money had even flowed.

Start of construction and progress

The actual construction work on the bridge officially began on December 12, 2015. The start of construction was accompanied by a festive ceremony in the presence of Prime Minister Hasina Wajid. The construction of the access roads and the hydraulic engineering work had already started in 2013/14.

On July 6, 2014, the government announced its intention to build a new settlement near the bridge at Maua. In view of the increasing number of Islamist-motivated attacks on foreigners since 2015 , additional security guards have been provided since October 2015 to protect foreign specialists working on bridge construction.

On September 30, 2017, the first of the planned 41 trusses was placed on two bridge piers. On this occasion, the government of Bangladesh emphasized sticking to the opening date at the end of 2018. However, a government commission report in November 2017 stated that the project would probably not be completed until 8 months later, i.e. around mid-2019. By June 29, 2018, 5 trusses had been installed. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina blamed the delays in building the bridge on the “false allegations” of corruption, which led to the World Bank and lenders withdrawing their financial commitments. This has also damaged Bangladesh's international reputation. On February 6, 2018, Finance Minister Muhith announced June 2019 as the likely opening date.

On April 3, 2019, the Chinese construction company requested an extension of the contract, which expired at the end of 2019, to June 2021. This was justified with difficulties in the river bed, which would have led to the design of 22 piers being changed.

On July 15, 2019, all 294 steel tubes for the 44 bridge girders were placed in the ground. The 17th truss was put on on November 27, 2019.

The global spread of the COVID-19 pandemic from January 2020 resulted in delays. Of the 980 Chinese citizens who were involved in the construction of the bridge on site, 332 traveled to China for the Chinese New Year celebrations in mid-January and were subsequently largely unable to return due to the quarantine measures imposed. Nevertheless, the Chinese ambassador to Bangladesh stated that the bridge project would be completed safely in 2021.

The 30th truss was installed on May 29, 2020.

Discussions about naming

At the time the bridge was being built, a representative of the ruling Awami League proposed that the bridge be named after Begum Fazilatunnesa Mujib, mother of Prime Minister Hasina Wajed . If this proposal were implemented, the two largest bridges in Bangladesh would then be named after the prime minister's parents (the Bangabandhu Bridge commemorates the father). Other Awami League MPs suggested naming the bridge directly after the Prime Minister. Since the main opposition party, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), has not been represented in parliament since the parliamentary elections in 2014 due to its election boycott between 2014 and 2019, there was also no parliamentary opposition to these named immortals by leading Awami League politicians. In the past, however, such names have not shown themselves to be capable of reaching a consensus in the opposition. When a BNP-led government came into office after the 2001 parliamentary elections , it promptly renamed the Bangabandhu Bridge the “Jamuna Multipurpose Bridge”. On October 5, 2018, Transport Minister Quader stated that the bridge would simply be named after the river.

Web links

- Padma Multipurpose Bridge Project , Bangladesh Bridge Authority

Individual evidence

- ^ Padma Multipurpose Bridge Project. Bangladesh Bridge Authority, archived from the original on July 23, 2016 ; accessed on July 17, 2016 (English).

- ↑ Mohammad Al-Masum Molla: Padma Bridge is the world's 25th longest bridge. Dhaka Tribune , December 8, 2015, accessed July 17, 2016 .

- ↑ a b c d e W.K. Wheeler, RJ Aves, CJ Tolley: Detailed design of the Padma Multipurpose Bridge, Bangladesh - An overview. IABSE-JSCE Joint Conference on Advances in Bridge Engineering-II, 8. – 10. August 2010, Dhaka, Bangladesh. ISBN 978-984-33-1893-0 . PDF

- ↑ Government increases Padma Bridge cost by 29%. January 6, 2016, accessed July 23, 2016 .

- ↑ Subir Bhaumik: Bangladesh takes bold step to bridge Padma. al Jazeera , April 18, 2013, accessed July 23, 2016 .

- ↑ Implementation Completion Report (ICR) Review - Bangladesh Padma Multipurpose Bridge Project. World Bank - The Independent Evaluation Group, 2012, accessed July 23, 2016 .

- ↑ a b Shakhawat Hossain: Chinese contractor seeks time extension till June 2021. New Age , April 3, 2019, accessed on April 22, 2019 (English).

- ↑ World Bank cancels Bangladesh bridge loan over corruption. BBC News, June 30, 2012, accessed July 23, 2016 .

- ^ ADB Statement on the Padma Multipurpose Bridge Project. Asian Development Bank, February 2013, accessed July 17, 2016 .

- ^ JICA over with Padma bridge project. bdnews24, June 19, 2013, accessed on July 23, 2016 .

- ^ Padma bridge project well on track. Dhaka Tribune, February 2, 2015, accessed July 23, 2016 .

- ^ Govt starts preparing year-wise budget for Padma Bridge project. LankaBangla Financial Portal, February 6, 2013, accessed July 23, 2016 .

- ↑ UNB: PM: A bank MD's removal led to Padma fund cancellation threat. January 17, 2016, accessed July 23, 2016 .

- ↑ Nava Thakuria: Bangladesh PM's Vendetta Against Grameen Bank's Yunus. asiasentinel, January 26, 2016, accessed on July 23, 2016 .

- ^ Hasina opens main work of Padma Bridge. Dhaka Tribune, December 13, 2015, accessed July 17, 2016 .

- ↑ Shohel Mamun: One-fourth work of Padma Bridge completed. Dhaka Tribune, February 15, 2016, accessed July 17, 2016 .

- ↑ Rabiul Islam: Govt plans to build a city near Padma bridge. Dhaka Tribune, July 6, 2014, accessed July 23, 2016 .

- ^ 'Extra security for foreign staffs in Padma Bridge project'. Dhaka Tribune, October 10, 2015, accessed July 23, 2016 .

- ↑ Padma Bridge becomes visible as first span installed. bdnews24.com, September 30, 2017, accessed January 6, 2018 .

- ↑ Doubts over meeting Padma Bridge construction deadline. The Financial Express (Bangladesh), November 27, 2017, accessed May 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Shohel Mamun: Padma Bridge progress: Dream of millions coming true. Dhaka Tribune, July 8, 2018, accessed September 23, 2018 .

- ↑ False graft claim caused Padma bridge delay: PM. The Daily Star, February 15, 2017, accessed September 23, 2018 .

- ↑ Padma Bridge will be ready for traffic from June 2019: Muhith. The Independent (Bangladesh), February 6, 2018, accessed September 23, 2018 .

- ↑ Tanjil Hasan: Padma Bridge piling work completed. Dhaka Tribune, July 15, 2019, accessed September 21, 2019 .

- ^ Tanjil Hasan: 17th span of Padma Bridge installed. Dhaka Tribune, accessed January 7, 2020 .

- ↑ Shohel Mamun: Chinese envoy: Padma Bridge work to end by 2021. Dhaka Tribune, March 3, 2020, accessed on March 26, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Tanjil Hasan: 30th span of Padma bridge installed. Dhaka Tribune, May 30, 2020, accessed June 10, 2020 .

- ↑ Padma bridge to be named after Sheikh Hasina, says Obaidul Quader. bdnews24.com, September 29, 2018, accessed October 24, 2018 .

- ^ Bangabandhu Bridge gets back its old name. The Daily Star, January 20, 2009, accessed October 24, 2018 .

- ↑ Padma bridge to be named after the river: Cuboid. The Daily Star, October 5, 2018, accessed January 20, 2019 .