Pearl (poem)

Pearl is a Middle English bar rhyming poem from the 14th century, written by an unknown author around the year 1392. It belongs to materially contemporary popular genre of Arthurian literature and within the Gawain - romances . In terms of content, however, there is no direct connection between the three poems and the romance. These works were taken over from Sir Robert Cotton's collection in the 18th century , first published in 1864 and analyzed several times since then.

background

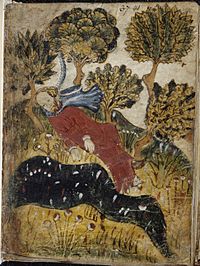

Pearl is one of four poems within the anonymous manuscript Cotton Nero Ax (Art. 3), which has been in the British Library of the British Museum in London since 1753 . The poem is illustrated with four pictures. On Pearl follow Purity (or Clean Ness ) and Patience and romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight ; the latter is based on the Arthurian poetry.

There are various theories about the anonymous medieval writer. Due to the dialect, which refers to the West Midlands of England, especially south-east Cheshire and north-east Staffordshire , it is assumed that the author or commissioner came from Staffordshire. From the words "Huge de" recorded in the manuscript immediately before the romance around Sir Gawain, an attempt was made to infer the possible author or owner of this manuscript. They allegedly point to a "Hugo Massey". This thesis is supported by a word “mass” or “masso” in the text of the also anonymous poetry St. Erkenwald , which is attributed to the same author because of the dialect used and the temporal proximity. According to other opinions, these manuscripts were made for a Stanley family in the West Midlands.

There are arguments that suggest that the author of the four works could have been the same person. Signs for this thesis:

- the stylistic similarity and the use of vocal alliteration

- the use of rare words found in two or more of these scriptures and no other known Middle English texts

- strict Christian faith orientation of the texts

This view is represented, for example, by Henry L. Savage in The Gawain-Poet: Studies in his background and his personality (1956) and Charles Moorman in The Pearl-Poet (1968). However, it could also have been a question of several scribes from the same office, who were based in an area with a special dialect.

content

The poet tells of how he lost his precious white pearl in his garden. Again and again he went to this place where it slipped from his fingers. One day in August, the scent of herbs and flowers put him to sleep on a little hill. He dreamed that he was on a distant unknown beach . It was a world of crystal cliffs , vast expanses of forest, and beaches dotted with precious pebbles. The sight made him forget all his grief and he wandered until he came to a river beyond which he suspected paradise . There he saw a girl at the foot of the cliff, whose dress seemed to be made of white pearls. He recognized her and asked if she was his pearl that he had lost. A longer dialogue ensued between the two, in which the dreaming realized that his pearl was not lost, since she was allowed to live with countless other pearls in this wonderful place. Not wanting to lose her again, he asked how he could get to her. The girl replied with Christian parables and asked him to trust in God's grace . She even gave him a glimpse of the Heavenly Jerusalem , the city of God. But when he tried to cross the river to get to the girl, he woke up. Filled with a spiritual strength and confidence, he rose from the hill in his garden.

construction

The poem, which has a total of 1212 verses, consists of 20 sections with 5 stanzas each; except for the 15th section alone, which comprises six stanzas. Each of the 101 stanzas has 12 verses on only three rhymes, which are used as cross rhymes in the rhyme scheme

- [abab: abab: bcbc]

are arranged.

The sections from 60 verses - the fifteenth from 66 - are each introduced by a capital letter . With the exception of the first verse in a section, all the first and last verses of his stanzas each have a word or partial word in common, which is used again in the first verse of the following section. Through this word all stanzas of a section are linked with each other in terms of content, and because it is also taken up again in the first verse of the following section, through all 20 connecting words also the whole poem. Since the connecting word of the last section appears in the first verse of the first section, this chain that runs through the entire poem is even closed cyclically.

“The language is dazzling, the metrical form is artistic; Every 12 lines that preserve the alliteration in the manner of the stick verse are bound to a stanza by end rhymes , every 5 such stanzas are connected by the same reversal , and recurrence of the same word (concatenatio) connects the first line of stanzas with the last of the preceding ones. The last line of the last, 101st stanza ties in with the wording of the first. "

| Rhyme scheme | Middle English | Modern English according to Tolkien | Free translation German | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | “O pearl,” quoth I, “in perles pyght, | "O Pearl!" said I, “arrayed in pearls, | "Oh pearl!" I said, "wrapped in pearls, | ||

| b | Art thou my pearl that I haf playedned, | Are you my pearl whose loss I mourn? | Are you the pearl that i lost | ||

| a | Regretted by myn one on nyghte? | Lament alone by night I made, | The night was filled with sorrow | ||

| b | Much longeyng haf I layned for thee | Much longing I have hid for thee forlorn, | Much longing for you emerged from me | ||

| a | Sythen into gresse thou me aglyghte. | Since to the grass you strayed from me. | Ever since you lay hidden, wrapped in grass. | ||

| b | Pensyf, payred, I am forpayned, | While I pensive waste by weeping worn, | As I lost myself in painful grief | ||

| a | And thou in a lyf of lykyng lyghte | Your life of joy in the land is laid | If you lived in the land of joy | ||

| b | In Paradys earth, of stryf unstrayned. | Of Paradise by strife untorn. | In paradise on earth, where quarrels no longer occur. | ||

| b | What wyrde has hyder my juel vayned | What fate hath hither my jewel borne | What lot brought forth my jewel here, | ||

| c | And don me in thys del and gret daunger? | And made me mourning's prisoner? | And brought such great suffering to me? | ||

| b | Fro we in twynne wern towen and twayned | Since asunder we in twain were torn, | We were torn in two before | ||

| c | I have a joyles jueler. " | I have been a joyless jeweler. " | I was just a joyless jeweler. " | ||

symbolism

The pearl or jewel and the number 12:

- In the description of the New Jerusalem in the Revelation of John : “And the twelve gates were twelve pearls, and each gate was of one pearl; and the streets of the city were pure gold like translucent glass. "

- The pearl as a symbol for the soul, the bride of God or the daughter

- 12 may represent the number of the apostles and the foundation stones of New Jerusalem. In addition, the city has a side length of 12 furlong each , which makes 144. This number possibly indicates the 144,000 virgins in the apocalyptic vision of the New Jerusalem.

- 12 is the number of verses in each stanza. There are 1212 verses in total.

reception

The poem was interpreted allegorically by William Henry Schofield in 1904 . He saw in the figure of the girl an embodiment of innocence and virginity. According to other scholars, the text is an elegy on the death of the poet's daughter. The poem describes the sadness and pain of the death of a two-year-old child. The portrayal, which is very vividly reproduced, ends with the narrator being seized by a deep feeling of trust in God .

Influence on Tolkien's mythology

The philologist J. RR Tolkien and the specialist in medieval Germanic languages Eric Valentine Gordon (1896–1938) have reinterpreted the medieval romance of chivalry Sir Gawain and the Green Knight . Gordon was in 1953 a reception of the poem Pearl out in the Tolkien a chapter on Form and Purpose ( shape and purpose authored) of the poem. David Scott Kastan suspects that the poem Pearl had an influence on the description of the Elf Galadriel in the mythology of Tolkien . Even in Thomas Alan Shippey's opinion, Pearl had an influence on this image. He compares Lothlórien (the name means flower dreamland), for example, with the landscape that the dreamer faces in the poem. When someone enters this land or the garden, all worries and sorrow fall away from him. While it says in Pearl : “Garden my goste al greffe forʒete” (The garden made my spirit forget all grief) it says in the Lord of the Rings about Lothlórien: “There was no mistake in the land of Lórien” or “Here no heart could die in winter Summer or spring mourn. ”Shippey compares both, the path of the father, who first crosses the border to the dream world; as well as that of the figures at Tolkien, who first wade the river Nimrodel (a river named after an elf named "the White Lady") - which alleviates their grief over the loss of Gandalf and washes them clean. In both cases, the second boundary is a river that the father cannot cross or step in the poem, since it represents the threshold to death, while the companions can only use Elvish ropes over the Celebrant (Silver Run) into the protected interior of the land of Lórien can reach, although they must not touch the water.

Modern theater

Thomas Eccleshare used the poem as the basis for the cartoon-like play Perle , which ran in 2013 at the Soho Theater in London. Here the dream vision of the poem Pearl was projected into a modern, bizarre multimedia world, with the basic theme of painful loss and grief being retained.

literature

expenditure

- Richard Morris, British Library: Early English alliterative poems, in the West-Midland dialect of the fourteenth century: copied and edited from a unique manuscript in the library of the British Museum, Cotton, Nero A x. Trubner and Co, London 1864, OCLC 893697347 . ( Pearl, Cleanness, Patience )

- Israel Gollancz , British Library: Pearl, Cleanness, Patience and Sir Gawain: A facsimile of British Museum MS Cotton Nero Ax Oxford University Press, London / Toronto / Rochester, NY 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-722162-4 (reproduction) .

Research literature

- Wilhelm Georg Friedrich Fick: To the Middle English poem of the pearl. A sound examination. Lipsius and Ticher, Kiel 1885, OCLC 457963622 .

- William Henry Schofield: The nature and fabric of the Pearl. With an appendix concerning the source of the poem. The Modern Language Association of America, 1904, OCLC 26406707 .

- Charles Grosvenor Osgood: The pearl, a middle English poem. DC Heath & Co., Boston / London 1906, OCLC 352031 .

- Israel Gollancz, British Library: Pearl. An English poem of the fourteenth century. GW Jones, London 1918, ( archive.org ).

- Eric Valentine Gordon: Pearl. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1953, OCLC 234699 .

- Robert J. Blanch: Sir Gawain and Pearl: Critical Essays. Indiana University Press, Bloomington / London 1966, OCLC 557237606 .

- John Ronald Reuel Tolkien: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo. Allen & Unwin, London 1975, ISBN 0-04-821035-8 . (Translation into modern English)

- Ewald Standop , Edgar Mertner : English literary history. 3rd expanded edition, Quelle & Meyer Verlag, Heidelberg 1976, ISBN 3-494-00373-4 , p. 103 ff.

- Seeta Chaganti: The medieval poetics of the reliquary: enshrinement, inscription, performance. Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-230-60466-7 , (Chapter 4).

Web links

- Sarah Stanbury: Pearl. (Middle English text) and introductory text . on d.lib.rochester.edu (English, 2001)

- Pearl by JRR Tolkien. on allpoetry.com (Tolkien's translated version)

- Pearl. (Middle English text with translation into modern English by William "Bill" Stanton)

- Karen A. Sylvia: Living with Dying: Grief and Consolation in the Middle English Pearl. on digitalcommons.ric.edu

- The Pearl. on theodora.com

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Cotton Nero Ax and the “Pearl Poet”. at bostoncollege.instructure.com.

- ↑ Pearl and the Pearl Poet. ( Memento of December 2, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF) on web.ics.purdue.edu.

- ^ A b Albert C. Baugh, Kemp Malone: The Literary History of England. Volume 1: The Middle Ages. Routledge, London 1994, ISBN 0-415-04557-6 , 2003 edition, pp. 233-235. ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Walter F. Schirmer, Ulrich Broich, Arno Esch, et al .: From the Old English Period to the Baroque. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-110-94947-4 , p. 168, Pearl, Purity, Patience.

- ↑ Revelation - Chapter 21 - The New Jerusalem on bibel-online.net.

- ^ Gershom Scholem: Origin and Beginnings of the Kabbalah. P. 154 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ The 12 precious stones as the foundation stones of the wall. On johannesoffengestaltung.ch.

- ↑ Christian L. Beck: Illumination of the Revelation of Jesus Christ. P. 569 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Books by JRRTolkien - Pearl on tolkienlibrary.com.

- ↑ Michael DC Drout: JRR Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge, New York 2007, ISBN 0-415-96942-5 , p. 504 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ David Scott Kastan: The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2006, ISBN 0-19-516921-2 , p. 202 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Tom A. Shippey, Helmut W. Pesch : The way to Middle Earth: how JRR Tolkien created "The Lord of the Rings". Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-608-93601-8 , pp. 274-275 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ A Medieval Gem: Pearl at Soho Theater. ( Memento from September 23, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) on onestoparts.com (Review, English).

- ↑ pearl. ( Memento of July 14, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) on sohotheatre.com.