European history and mythology in Tolkien's world

European history and mythology in Tolkien's world sheds light on those backgrounds of the Nordic mythology and history in particular , which flowed into the mythological concept of the work of Middle-earth John Ronald Reuel Tolkien and its imagined world.

Tolkien was a linguist and avowed Catholic, but understood his poetry by no means as an allegory, but as an independent creation in the literal sense. It contains numerous echoes and borrowings from the medieval heroic sagas, the Icelandic saga literature and from the Germanic, Finnish and Welsh-Celtic mythologies with which he was familiar due to his linguistic studies. Tolkien also used narrative material from classical Greek mythology and heroic epics such as the Homeric Iliad or the depiction of the fall of Atlantis by Plato as well as various fairy tale motifs as written down by the Brothers Grimm . Through his literary circle in Oxford, the Inklings , to which Charles Williams , CS Lewis and Owen Barfield belonged, Tolkien also became familiar with contemporary esotericism in its Christian / Romantic form.

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien

Tolkien (* 1892, † 1973) was a British professor of philology (linguistics and literature) at Pembroke College (1925 through 1945) and Merton College (1945 to 1959) of the University in Oxford . In his studies he dealt in detail with medieval, mostly Anglo-Saxon texts, for example with the last war of King Alfred , the Norse song of the gods Skirnir or an English version of the Bible from the 12th century by a monk named Orm (snake), which is known as Ormulum is known. Furthermore, Tolkien had a great interest in the medieval ideas of the magic of Anglo-Saxon burial places or in the representations of monster-like apparitions on the finds in a ship's grave in Sutton Hoo . But also formative events such as the early death of his parents or his love for his future wife Edith Bratt found their way into Tolkien's stories about Middle-earth.

Influenced by contemporaries

The search for other worlds is considered to be a typically contemporary aspect of Victorianism. Verlin Flieger sees in George du Maurier an author with great parallels to Tolkien's life and writing, whose novels Peter Ibbetson (1891) and Trilby (1894) would have had an impact similar to Tolkien's fantasy.

In relation to Tolkien's work, references to contemporary racism and ideas of geopolitics were occasionally accused, in Germany by Niels Werber , among others , who in no way question the success of the corresponding books and the entire literary genre.

Tolkien's stories about Middle-earth contain echoes from the works of William Morris ( Arts and Crafts Movement , here in particular the poetry and narrative style in the romances), from which he also borrowed content-related elements such as the swamps of the dead or the bleak forest (Mirkwood). Further influences can be found in Owen Barfield 's children's book The Silver Trumpet , the History in English Words and Poetic Diction , but also in the story Marvelous Land of Snergs by Edward Wyke-Smith, which is partly in the depiction of the events around Bilbo Baggins in the book Find the little hobbit again.

Tolkien himself described the writing of fantasy in his On Fairy-Stories 1939 - he himself uses the term fairy-stories, which could be translated more as "fairy tale" - as an act of creation in the Christian sense, in which words are the essential tool. He refers, among other things, to the Greek Pneuma , which originally could mean "spirit", "breath of wind" and "word". According to Tolkien, words and terms not only describe the author's imagination or a rediscovery of forgotten knowledge in the sense of Plato's Timaeus dialogue (which, in addition to the Atlantis saga, also contained fundamental considerations on human perception) or the imagination in the sense of Samuel Taylor Coleridge , but create their own World. Fundamentally important for Tolkien was Owen Barfield's anthroposophically shaped idea of a primeval semantic unit , according to which humanity in its beginnings already had a feeling of the cosmos and a participation in it, which has since been lost. Like the pneuma, the original terms initially formed larger semantic units that have since split up into different meanings. For Tolkien, as he later explained to Lewis, this consideration was central to his writing of Fantasy, which enables a return to a state, so to speak, before the Fall, which he considers to be a basic human need. Furthermore, he introduces the term eucatastrophe , a turn for good from the smallest beginnings, which he also describes as Christian-based.

Germanic influences

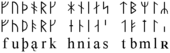

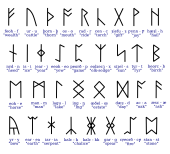

Middle-earth - Tolkien and Germanic mythology is the title of a non-fiction book by Rudolf Simek that deals with the influences of Germanic mythology on the works of Tolkien. In addition to the names and characteristics of important people and mythical creatures, it illuminates the overall geographic concept or the use of characters (runic script) through to literary works and motifs that could have influenced Tolkien's conception of Middle-earth.

“Trolls and dwarves everywhere, a cursed ring and a broken sword, good magicians and dangerous dragons: Tolkien's works, especially the Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings and the prehistory to them in the Silmarillion, are full of elements and motifs from North Germanic mythology come. This volume traces the most important names, fabrics and motifs that Tolkien took from old Scandinavian legends and mythology, the Eddas and sagas of the Icelandic Middle Ages and used in his newly created world of Middle-earth. "

Tolkien and Old Norse Literature

“I have spent most of my life […] studying Germanic matters (in that general sense that includes England and Scandinavia). There is more power (and truth) in the Germanic ideal than the ignorant believe. [...] Anyway, I have a hot personal grudge against this damned little ignoramus of Adolf Hitler [...]. Because he ruined, abused and corrupted the noble Nordic spirit, that excellent contribution to Europe that I have always loved and tried to show in its true light, so that it is now cursed forever. "

| Old Icelandic sagas - ancient sagas | Edda - Prose Edda | More sagas | Medieval texts - heroic epics |

|---|---|---|---|

Rudolf Simek suspects that Tolkien was particularly fascinated by the song edda and the Icelandic prehistoric sagas, as he mentioned them several times in his letters. These texts deal with Scandinavian history before and during the Viking Age up to the year 870. In particular, the influence of the Völsunga saga and the Beowulf , on which Tolkien wrote a scientific treatise (The Monsters and the Critics) , have flowed into his mythology.

Motifs from mythology and heroic sagas

In Germanic mythology, two special rings play an important role: One is Draupnir, Odin's arm ring, from which eight rings of equal value drip off every ninth night; hence its name means "the dropper". Odin throws this ring into the fire in which his son Balder is buried. Elements that can be found in Tolkien's ring are the connection between the "master ring" and the dependent, subordinate rings as well as the fire into which it is thrown. After losing his ring, Sauron tried to get it back, because without it he had little power over other beings. In contrast to Sauron, Odin recovers his ring from the Hel . Son Hermodr unsuccessfully asks the goddess of the underworld for the return of his brother, but only receives Odin's ring back. The number of rings ruled by Sauron's "One Ring" (nine for the humans, seven for the dwarfs) is also a number that can be divided by eight. Sauron's ring had no influence on the three rings of the elves , as these were forged by the elves without his intervention, so that Sauron could not take them.

The second is the Ring of the Andvari , the “Andvaranaut”, which is commonly known as the “Ring of the Nibelung” from the Nibelungen saga. There is a curse on this ring that brings death to anyone who has it - this is how it is described in the Völsunga saga (Chapter 15). This ring basically determines the fate of its wearer - just like in Tolkien's story, where it is destroyed in the fire of Mount Doom.

- The dragon slayer

The motif of the dragon slayer can already be found in the Beowulf . The hero Beowulf must fight a fire-breathing dragon that ravages his lands. He sets out with a crowd of followers to destroy them, but is himself killed. Only one of his companions is at his side at the crucial moment. This element can be found in the story of the children of Húrin, when Túrin Turambar fatally injured the fire dragon Glaurung by stabbing the unprotected underside of the dragon with a sword. Túrin also dies shortly afterwards, albeit not directly from an injury, but from the dragon's deception and malice when he has to recognize the truth about his destiny predestined by evil and takes his own life.

In the New Testament it is the archangel Michael who fights with the devil in dragon form. Although he does not kill him, he hurls him down to earth. With Tolkien, too, there is evil behind the dragons in the form of the exiled Valar Melkor, who covers the earth with horror.

Siegfried is probably the best known of the dragon slayers; therefore it is not surprising that Tolkien also incorporated this figure into his mythology. In the story of the children of Húrin, it is Túrin Turambar (Victory Heart of the Master of Fate) who takes on this role and who is said to return in the Dagor Dagorath (battle of battles, comparable to the Germanic Ragnarök) and Melkor, who one way back after Arda (to earth) has found the fatal blow. His nickname after the killing of the dragon was, similar to Siegfried “the dragon slayer”, Túrin “Dagnir Glaurunga” (slayer of Glaurungs).

This danger from dragons also existed in Celtic mythology. In the story Cyfranc Lludd a Llefely, for example, the hero Llefely defeats a dragon that threatens the land of his brother Lludd .

At Tolkien, the dragons are ultimately defeated by the skill of the brave hero who finds their vulnerable spot. In the Hobbit, it is the archer Bard, whose arrow hits Smaug at the exact point that is not covered by a gem or gold. And in the Silmarillion it is Túrin, who hides in a ravine and so Glaurung can ram his sword from below into the soft belly.

Some critics believe that Tolkien took parts of the Lord of the Rings plot directly from Richard Wagner's opera . Since both have resorted to the Völsunga saga and the Nibelungenlied as sources for their material, parallels are to be expected from this alone, however, say Tom Shippey or Gloriana St. Clair.

Tolkien stated to his publisher: “Both rings were round, and here the resemblance ceases. - Both rings were round, and this is where the similarity ends. ”In his biography, Humphrey Carpenter reports on Tolkien that he had little interest in Wagner's interpretation of Germanic myths.

- The king in the mountain and the shadow army

The motif of the returning king in or under the mountain can be found in several popular traditions, such as King Arthur ( Cadbury Hill ), Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa ( Kyffhäuser ) or Emperor Charlemagne ( Untersberg ). At Tolkien this legendary material is taken up on the one hand by the dwarf king Durin (here only as a sleeping king who will awaken again), on the other hand by the king of the army of the dead in Dwimorberg, who is called into battle by Aragorn in the greatest need . This motif in turn recalls the last battle in which Odin is supposed to lead the army of the dead warriors at the end of the world (Ragnarök). But there are other descriptions of so-called armies of the dead, such as the Harians , which Tacitus describes in his Germania , or the Einherjer and the wild hunt in Germanic mythology.

In the Völsunga saga (Chapter 12) the motif of the broken sword "Gram" appears, which later belongs to Siegfried . This sword was previously owned by his father Sigmund , who is killed in a battle, where Odin himself refuses to support him and breaks it on his spear. (Compare the dark traits of Odin - Sauron) The dying commissioned with the words “Take good care of the parts of the sword: A good sword will be made out of it, it will be called grief, and our son will bear it and perform great deeds with it . “ Hjördis to keep the parts of the sword for their son. Very similar is the description in The Lord of the Rings, where the sword "Elendils" of Isildur's father breaks in battle. Isildur has it brought to Imladris (Rivendell), where it is kept until it is reforged for Aragorn, his heir. The Gísla saga Súrssonar also speaks of a broken sword (Grásíða) - but this is reworked into a spearhead that was provided with magical symbols.

The sword in Tolkien's story, like “Gram” and “Excalibur”, could cut stone. Another aspect related to King Arthur's sword is the fact that it can only be wielded by the man who turns out to be the true king. This is true of Aragorn, as he was the last in a long line of ancestors who had an innate right to the throne of Gondor and Arnor. This is clearly shown when Aragorn demands allegiance from the king of the army of the dead, who only recognizes him when he takes out his sword. According to legend, the metal for the manufacture of the sword "Excalibur" was iron from meteorite rock, as was Turin's sword "Anglachel" ("iron flame star", later it was called "Gurthang" or "Mormegil") forged from a fallen star has been.

Other important swords in Tolkien's history are the “Glamdring” (Turgon, Gandalf) and “Orkrist” (Thorin Eichenschild's sword) blades from elven smiths in Gondolin.

- Revenants , grave monsters

The grave monsters mentioned in Lord of the Rings also have models in Norse mythology. As haugbúar, so-called hill dwellers, living corpses in the burial mounds of the Vikings or from the Bronze Age were called, who protected their graves from robbers.

Tolkien had translated and edited the medieval stories by Sir Orfeo and Sir Gawain , so that motifs in Middle-earth can also be found from them. It's about courting or reclaiming a beautiful woman. A formative motif that runs through the history of Middle-earth, but which also determined Tolkien's own life and his love for Edith Bratt , is the fulfillment of an insoluble task in order to receive the hand of the chosen. In the Silmarillion it is the story of Beren and Lúthien, in which Beren has to cut a Silmaril from the crown of Melkor and bring it to the Elven King Thingol. Thingol believes that Beren will find death in this way and that he can get rid of him this way, because he does not want to give his daughter Lúthien to a wife. In the Lord of the Rings it is Aragorn who only gets the daughter of Elrond as a wife if he proves himself worthy of a king and recaptures the crown from Gondor and Arnor. Father Francis Morgan had imposed a similar condition on 16-year-old Tolkien, forbidding him from any contact with Edith Bratt until he was of legal age. But her love stood the test.

- The puzzle contest

In the Vafþrúðnismál , a song from the Edda about the giant Wafthrudnir , the Germanic god Odin challenges him to a competition. Odin tries to fathom how clever the giant, who is generally considered to be very wise, really is. The two compete in a puzzle competition. In the Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks konungs there is also a similar competition between Heiðrek and Gestumblindi .

This motif of the guessing game can be found in Tolkien's book The Little Hobbit when Bilbo meets Gollum in the orc cave. The point here is that if Bilbo wins, Gollum will not eat him and he should show him the way to the exit. Greg Harvey compares this puzzle contest in his book The Origins of Tolkien's Middle-earth For Dummies with the story of King Oedipus and the riddles of the Sphinx . Here, too, it is about answering the questions correctly in order not to be killed by the Sphinx. One of these puzzles was very similar in both cases.

"None of the legs lay on one leg, two legs sat on three legs, four legs didn't go away empty-handed."

“It is four-legged in the morning, two-legged at noon, and three-legged in the evening. Of all creatures it changes only with the number of its feet; but when it moves most of the feet, the strength and speed of its limbs are the least. "

In both cases, “human” is part of the solution.

- The white fairy

Even in the Arthurian legend, a woman named Guinevere is the English name for the Celtic Gwenhwyvar (the white fairy, the white spirit). She was kidnapped, freed by Sir Lancelot and Sir Gawain and brought back to King Arthur. In Tolkien's story there are several female figures who have both names and external similarities with this legendary figure. The first important woman is the Maia Melian (gift of love), who meets the Elf Elwe Singollo (Elu Thingol) in the forest of Brethil in the area of the later Doriath . He immediately fell in love with her and did not return to his people, who were on their way to the west and moved on without him. Melian is the mother of Lúthien and taught her and Galadriel much about the care of the trees and plants of Middle-earth. Melian is the most beautiful woman in all of Middle-earth and has the gifts of foresight, compassion and wisdom as well as the power to sing magic melodies and the so-called belt, a kind of invisible, impenetrable fence to work around her realm. Other figures known as "White Woman" or "White Lady" are Nimrodel (white noblewoman), she is an elf who got lost in the forests of Middle-earth, her beloved Amroth drowned off the coast of Anfalas near the city, who later drowned after him named "Dol Amroth" (Hill of Amroth). Galadriel is also reverently referred to by Faramir as the "White Lady". What these characters have in common is that they were all ultimately separated from their lovers (through death, departure or exile). So-called " white women " are also known from many ghost stories, especially in old English walls or castles.

- The Eärendil myth

In the Edda there is a story told in which the god Thor rescues a man named Aurvandil from a river and carries him to the bank in a basket. However, a toe that protruded from the basket was frozen. Thor broke it off and threw it high into the sky, where it has since been visible in the night sky as Aurvandils tá (Aurvandil's toe). Tolkien incorporated this story in a modified form into his mythology. With him it is the half-elf Eearendil, who sails with his ship west to Valinor to ask the Valar for assistance. This request is fulfilled, but he is not allowed to return to Middle-earth, instead he and his ship are seated in the sky and since then have been sailing across the night sky with a shining Silmaril on his forehead as an evening star. The name Eärendil is also based on the Old English name for the morning star (Earendil) or in Middle High German Orentil, Orendel. This suggests that the eponymous poem Orendel from the minstrel poetry also had an influence on this figure, which is also known as Eearendil the seafarer . Orendel sets out with a fleet and is the only one to survive this trip. Rudolf Simek also suspects the poem Christ von Cynewulf as a source .

- The Istari

Arnulf Krause sees the Germanic priests as a possible origin for the magicians in Tolkien's story in his comparison between Middle-earth and the real world. While Caesar claimed that the Germanic pagans knew no priests, Tacitus describes in the Germania a group of people who were the only ones allowed to judge others or to punish them. They acted on the instructions of the respective gods, carried symbols and signs into the battles that came from sacred groves . Her duties included holding the public oracle and maintaining order and tranquility at thing meetings . Among the Anglo-Saxons, the name “æweweard” ( Old High German êwart , roughly “lawyer”) was handed down for this Germanic priesthood. Another name that comes very close to the "Istar" Tolkien can be found in a report by the Beda Venerabilis , who mentions it in a description of the baptism of King Ewin in 630 as "Witan" (wise counselor). The word "Istar" also means "wise man".

According to Krause, however, the "Istari" show far more similarities with the Celtic druids , especially with the magician Merlin . One of the tasks of the druids was to advise the rulers and to confuse the enemies through magic and illusion during combat operations. Merlin is a term used as advisor to King Arthur, which can be traced back to a bard and seer with the name "Myrddin", who is said to have participated in a battle in 575. After the death of his tribal prince, he is said to have lost his mind and from then on roamed through the woods. In some legends, this first became "Lailoken" and later the wise magician Myrrdin, who was associated with many events in different places. In addition, he was said to have abilities such as knowledge of the processes in nature, the transformation into other shapes, the gift of the second face (prediction) or influencing the weather. The magician Gandalf is known as the gray wanderer and he is also said to have appeared where people needed his advice most urgently. He has very similar qualities and is considered a wise seer.

Celtic influences

Tolkien himself said after the book The Lord of the Rings was published :

"[...] the long-delayed publication of a great work (if you can call it that), in the type of presentation that I find most natural, from which I personally received a lot from studying Celtic things."

- The Celtic Harp

A symbol of the Celts, which was retained as a national symbol in the Irish harp, also plays a recurring role in the mythology of Middle-earth. The Lay of Leithian speaks of a triad of Elvish harpers. The first mention of this instrument is found as the instrument of the Elven prince Finrod Felagund, who played the Elvish harp when he first met the people who had immigrated to Beleriand. The dwarf Thorin Eichenschild also plays a harp in the dwelling of the hobbit Bilbo Baggins in Bag End. In Gondolin, one of the twelve elven families resident there was called the "House of the Harp", the leader of which was Salgant (harp player).

- The Welsh Dragon (Y Ddraig Goch)

Tolkien used the dragon motif in addition to his stories about Middle-earth in the children's book Roverandom (1927), where the white and red dragons appear, which alludes to the legend of the magician Merlin and King Vortigern , in which a red and a white dragon (Celts and Saxony) fought for supremacy in Britain. The 1928 poem The Dragon's Visit is also about a dragon.

- Opinion of a Germanic Medievalist and Celtologist

Helmut Birkhan says the following about the Celtic influence:

“In addition to the reception of mainland Celtic antiquity in the well-known comic series Asterix , the one of the island Celtic saga tradition by JRR Tolkien (1892–1973) was certainly the most effective. In his main work, The Lord of the Rings , the old Anglist from Oxford designed a mythical “fantasy world”, which is fed partly from Celtic and partly from Germanic traditions. [...] that the hobbit (a kind of gnome of sub-dwarf size - model was probably the Irish elf people of the leprechauns ) Bilbo Baggins (German: 'Baggins') came into possession of a ring, which his friend Gandalf (a kind of incarnation of the Germanic Wodan) recognizes as the ring that bestows the greatest power, [...] harassed by the orcs (from Irish: orc 'pig' and Middle Latin: Orcus 'underworld demon' contaminated), the ring-bearing hobbit Frodo (name of a Danish prehistoric king ) finally arrives to the goal. The destruction of the ring causes the downfall of the forces of evil and the departure of the hobbits to a "distant green land over the sea" (another world ), a thought that seems to be inspired by the Arthurian legend as well as by the end of Wagner's Götterdämmerung . As Tolkien associates, based on great mythological and philosophical knowledge, the claim that the content of the romantic trilogy comes from the Red Book of Westmark written by Bilbo shows . Tolkien knew the Red Book of Hergest , one of the main sources of the Welsh saga tradition, associated Hergest with the Anglo-Saxon Hengest 'stallion', one of the conquerors of Britain, and translated the name with the Welsh horse word march ... The fascinating thing about Tolkien's work is the fantastic, in coherent system of times, worlds, realms (people, hobbits, orcs , elves, giants ...), landscapes, languages (with their own grammar) and scripts. Tolkien's work [...] has remained the most important stimulus in fantasy literature to this day. "

The ancestors

- The vanished people

There are also echoes of Tolkien's Middle-earth in the island of Celtic legends. The stories in the Lebor Gabála Érenn (Book of the Capture of Ireland) have similarities with the immigrations into Middle-earth in its four ages.

While in Ireland the enchanting people of the Túatha Dé Danann defeated the demonic and monster-like Formóri , with Tolkien it was the Elven peoples who tried to assert themselves against the creatures of Melkor. Although the Túatha Dé Danann were defeated by the succeeding people of Gaedel (Goidelen) or Milesians , they did not disappear entirely from Ireland. According to legend, the sorcerer Amergin divided the land between the two groups, with the conquerors getting the lands on the surface and the Túatha Dé Danann the areas below. From then on, these lived as Síde in hills and caves or in the so-called Celtic Otherworld.

Tolkien also takes up this dwindling, because the Elves (who have a lot of resemblance to the Tylwyth Teg) leave Middle-earth towards Valinor or the offshore island Tol Eressea at the end of the third age, only a few remain behind in hidden realms. From then on they no longer play a decisive role in history, because the age of humans in Middle-earth begins. The ideas associated with the Celtic Otherworld (such as the designation as “land of youth” or “land of women”) describe a realm of paradisiacal conditions. Trees were to grow there that bore fruit continuously, animals were to live whose flesh was renewed, and cauldrons full of mead that ensured rebirth and happiness. The same applies to the land of Valinor, where the immortal Elves live happily and securely next to the Valar.

The immigration to Middle-earth (here especially Beleriand) in the first two ages can be summarized as follows: First came the three Elven peoples (Vanyar, Noldor, Teleri), then the three houses of the people (Elven friends) and finally the Easterlings. The Tír na nÓg (Land of Eternal Youth) can be seen as one of the models for the Immortal Lands (Valinor) and Lyonesse for the island of Númenor or Beleriand, both of which were lost in a flood disaster.

Opinions in articles about the Celtic influence on the concept of elves:

"Lothlórien with its mystical timelessness is strongly Celtic in tone, as are the swamps of the dead and the paths of the dead in a less pleasant way."

“When Tolkien took the name of the 'Elves' from Teutonic myth, he drew their soul from Irish legend. The story of their long defeat comes from the Irish legend, the motif of their ›fading‹ [...] "

Celtic legends

- The journey west

Further influences can possibly be found in the Immram Brain (Bran's seafaring), who after his trip to the Elven Island realizes that he is not allowed to return to his homeland Ireland as a human being, as only transience and death await him there. Tolkien's seafarer Eearendil has a similar experience because he is not allowed to return to Middle-earth. The positive image of the elves also comes from Celtic mythology, for example, in the legend of the cattle robbery , Cú Chulainn receives the support of an elven warrior from the Otherworld who watches over his sleep and heals his wounds. Many of these encounters with beings from the Otherworld are particularly portrayed in the narratives of the four branches of the Mabinogion .

Tolkien wrote a number of writings or poems on this, such as Éalá Éarendel Engla Beorhtast (The Voyage of Éarendel the Evening Star, 1914), The Happy Mariners (1915), The Shores of Faery (1915), The Nameless Land (1924/1927), The Death of Saint Brendan (around 1946) and the sequel Imram (published 1955) or Bilbo's Last Song (published 1974).

- Unfulfillable demands for getting a bride

Other Celtic elements are the Tochmarc (courtship), Aithed (kidnapping), Tóraigheacht (persecution), which can be found in the story of Beren and Lúthien. A similar, actually unsolvable bridal gift, as requested by Beren, can be found, for example, in the story of Culhwch and Olwen , where the hero has to master countless tasks in order to get the daughter of the giant Ysbaddaden as his wife. There is another parallel in the hunt for the comb and the scissors of the wild boar Twrch Trwyth . Instead of a boar, Beren must hunt down the wolf Carcharoth, who devoured the Silmaril, the bride price for Lúthien, which Beren must bring to Thingol. The metamorphoses into animal form (the children of Lir turn into swans, Gwydion and Gilfaethwy in the Mabinogion into wolves) can also be found in this story, when Lúthien and Beren turn into a vampire woman and a wolf by dressing in their peeled skin .

In both stories the hero also uses the help of a great prince (King Arthus and Finrod, the elf prince), both of whom show their rings as proof of their identity. They are each given almost impossible tasks that they can only solve with the help of a supernatural dog (Cavall and Huan). The two maiden mentioned in the stories have a charisma and loveliness, as if they were the personification of the beginning of spring, because wherever they go the flowers bloom at their feet.

The language of the elves

Tolkien himself wrote that in creating the Elvish Sindarin language he deliberately “gave it a linguistically similar (if not identical) character to the British Welsh ... because it seemed to him that this Celtic way of rendering legends and stories was his narrator Stories best fit. ”In his book Tolkien and Welsh, Mark T. Hooker looked for the origin of the names of people and places in Tolkien's history and found some that are actually identical to or very similar to Welsh .

Finnish influences

- The Kalevala

In the Kalevala, songs 31 to 36 tell of Kullervo , whose family is exterminated by his uncle Untamo before his birth. It seems like only his mother was spared. After his birth, attempts are made several times to kill him, but when this fails, he is enslaved and sold. Kullervo manages to escape and learns that both his parents and his sisters are still alive. However, this sister has disappeared. Kullervo meets her by chance and seduces her. When his sister learns that he is her brother, she drowns himself in the river and Kullervo later takes his own life by throwing himself on his own sword.

Many of these elements can be found in the story of the children of Húrin. When Túrin was a young boy, his father Húrin is apparently killed in the battle against Melkor. Túrin has to leave his pregnant mother because he is threatened with death or enslavement back home. He goes to Doriath, where he is received and raised like a son by the Elf King Thingol. There a quarrel breaks out, the Son of Man kills one of the Elves and flees. His mother has since given birth to a daughter who has grown into a young woman. Both set off to look for Túrin. Túrin also meets his unknown sister by chance or by bad providence and takes her as his wife. She is expecting a child from him when she learns from the dragon Glaurung that Túrin, who had recently inflicted a fatal wound on the dragon and is lying next to him as if dead, is her brother. Thereupon she throws herself desperately into the gorge the Teiglin. When Túrin wakes up and learns what has happened, he throws himself into his sword.

Greek influences

- Gyges' ring

Plato tells of a shepherd of the Lydian king Kandaules named Gyges . He finds a huge bronze horse with doors and a huge corpse in a crevice that has opened up after heavy downpours. Gyges descends and discovers a golden ring on the corpse, which he takes. When he is back with the other shepherds, he notices that the ring makes him invisible when he turns the ring head towards the palm of his hand. He then used this property of the ring to approach the queen, overthrow the king and usurp power.

- The Atlantean myth

The island of Númenor (the western one) shows clear parallels to the Atlantis described by Plato. The people who inhabit the area are considered to be particularly clever and skillful, their architectural achievements exceed the architecture of all other human races in Middle-earth and they are granted a far longer life than other people. Tolkien originally planned this part of the story as a separate tale about time travel, which Tolkien started with The Lost Road but never completed. Like Atlantis, Númenor sinks into the sea and with it many of the advanced achievements of this civilization. Here Tolkien himself gave a clear indication of this reference by choosing the name, because Númenor bore the name Atalantë (the sunken) after the sinking.

- The Iliad and Troy

In the story of Tuor and the fall of Gondolin , Tolkien tells of the fortress of the Elven King Turgon , which is well hidden and invincible and is ultimately captured by betrayal. This is not the only parallel to the history of the destroyed and for a long time undetectable city of Troy. Both the layout of the facilities and the plot around the events that lead to the demise are similar.

Both stories are about the favor of a woman described as extremely graceful. With Homer it is the beautiful Helena , who was considered the prettiest woman of her time, with Tolkien it is Idril Celebrindal (the lovely woman with the silver foot), Turgon's daughter.

Paris , the son of Priam (King of Troy), kidnaps Helena to Troy, whereupon her husband Menelaus takes up the pursuit with his army and attacks the city, but initially fails. After a long siege, they manage to take the city and destroy it forever by means of a trick ( Trojan horse , in which Menelaus hides himself). King Priam dies within his city, but Helena, like young Aeneas, can escape the city through a secret escape tunnel, where he was able to save the holy statue Palladion .

Even if in Tolkien both the roles of the figures and the position of the place are chosen differently, there are very similar motifs.

The Elf Maeglin has long had an eye on the pretty daughter of Turgon when suddenly a rival appears, the person Tuor . To his displeasure, he is not only received by Turgon, because normally people are not allowed to enter the city, but are soon married to Idril, who also gives him a son (Earendil). In the end, Maeglin reveals to her enemies where the secret entrance to the city is and thus exposes them to doom. Turgon falls in battle like Priam within the city walls. Idril, Tuor and their son Earendil escape through a secret escape tunnel and take the king's sword Glamdring with them, which later comes into the possession of Gandalf.

Slavic influences

Mythological names from the Slavic region can be found in the history of Middle-earth, for example Radagast , who lives in Rhovanion in a house called Rhosgobel. There is a very similar name for the Slavic god Radegast , who is associated with sun, war, hospitality, fertility and harvest. Likewise, the river name “Anduin” (long river) is said to have the same etymological origin as the Danube , which plays an important role especially for the Slavic peoples. The Khand and southeast location of Mordor where the inhabitants, the wild Variags, could originate in the Varangians have a people who settled in regions that belong to Russia, Belarus and Ukraine.

Borrowings from Grimm's fairy tales

Especially in the first ages, when the Elves and humans lived in the densely wooded areas of Middle-earth, there are motifs from the world of medieval fairy tales and oral traditions, as they were compiled and recorded by the Brothers Grimm. At that time, Middle-earth, like much of Europe in the early Middle Ages, was still covered by dense, large forests that were apparently full of danger and where wild animals lived. George Clark, Daniel Timmons, for example, compare these forests with descriptions as they are reproduced in the fairy tales of Hansel and Gretel or in Snow White . The warning given in the fairy tale Little Red Riding Hood that she shouldn't deviate from the path and go straight to her grandmother's house also indicates this threatening character of the forests. SK Robisch also mentions this fairy tale in connection with the wolf figures in Tolkien's work, since the werewolves, like Little Red Riding Hood, can speak. Furthermore, the motif of being devoured by the wolf and the later slicing of its belly can be found in the story of Lúthien and Beren. There it is the wolf Carcharoth who devours Beren's hand with the Silmaríl. He is later killed and the Silmaríl is taken out of his body.

Another fairytale motif in this story is the story of Rapunzel and her long hair, who was locked up in a tower. With this hair the witch and the prince could get up to her in the tower. Tolkien implemented this in a manner appropriate to his story. Lúthien loves Beren, who was sent by her father to cut the Silmaríl from the crown of the Dark Lord Melkor and bring it to her father as a bride price. She fears that something might happen to Beren on this mission and wants to follow him. However, her father locks her up in a very tall tree in a tree house and has the ladder removed. Using secret ingredients and with the power of a magic melody, Lúthien succeeds in making her hair grow so long that after a short time she can abseil out of the tree house and follow Beren.

Tolkien, on the other hand, borrowed the idea from the fairy tale Rumpelstiltskin that the real name of the dwarfs was not allowed to be revealed to anyone from a strange people and could not even be found on their gravestones. Tom Bombadil also shows similarities with the Rumpelstiltskin, but less in his character than in the hopping movement of this figure, singing his name.

Influences from European history

Funeral rites

The imposing barrows of the so-called megalithic cultures are already known from the Neolithic Age . An example of such a facility is at Newgrange , Ireland . Numerous barrows of different sizes and from several epochs can be found especially in the areas of Europe that were formerly populated by Celts or Teutons. Tolkien also took up this type of burial. The members of the royal families of the Rohirrim (horse people) were all buried in burial mounds near their capital Edoras , which were overgrown with grass and an anemone-like flower called "Simbelmynë" (Old English simbel = always; myne = remember). There were other burial mounds near the Shire east of the " Old Forest ", where the "Barrow Heights" were. These tombs were formerly built for the mighty kings of Arthedain and Cardolan , but were settled by grave fiends after the fall of the Kingdom of Arnor and the departure of most of the people from these areas. So they were only worshiped by the few Dúnedain of the north (western people to whom Aragorn belonged as a leader), but feared by ordinary people (for example the Bree-lands ) or hobbits and avoided this area.

Ship graves are a special form of these burials, as a complete boat is located in the burial mound, such as the Ladby ship . In some Icelandic sagas, boat graves are described ( that of Ingimundr in the Vatnsdæla saga - þorgríma in the Gísla saga - and a woman Unnr in the Laxdæla saga ).

Another special form of ship burial is exposure at sea in boats, as described for example in the Beowulf near Scyld and Sceaf , which were furnished with treasures and handed over to the sea. Tolkien wrote a poem about this called King Sheave , in which such a ship exposure is described. He also chose this form of burial for one of his heroes in Lord of the Rings . Boromir is placed in an elven boat by the man Aragorn, the elven prince Legolas and the dwarf Gimli, together with his sword, the horn of Gondor and the helmets of his slain enemies, it is placed on the Anduin (long river). This boat gets through the tumbling water masses of the Rauros Falls (the rushing ones) unscathed and is carried to its mouth, where it finally reaches the open sea.

In Minas Tirith (Tower of the Watch), however, the kings were buried in so-called royal tombs in sarcophagi , as they are also used by princely families in Europe. These were located in the city of Tolkien on the so-called Rath Dínen (Silent Street), which was secured by an additional gate that was only opened for funeral celebrations. This honorable burial was also granted to the deputy head dinners in the story.

Great Migration

"On! On! you riders Théodens! To grim deeds: fire and battles! Spear will shatter, shield shatter, sword day, blood day, before the sun rises! Now ride! Rode! Ride to Gondor! "

- The exodus of the Goths

Tolkien dealt with the history of the Goths , which the historian Jordanes recorded in his work Getica in Latin . This text tells of the exodus of the Goths under their leader Berig from the northern island of Scandza to Gothiscandza (coast of the Goths). There they defeated the Rugians and Vandals and moved further southeast to the Black Sea . The Goths were particularly praised as a people of cavalry warriors who fought their duels on horseback and were able to cover great distances in a short time. They mainly used lances or spears, which gave them a strategic superiority over the infantry troops. Only the Hunnic cavalry hordes armed with bows were superior to them in armed conflict, as the arrows had a greater range than lances and could also be carried in larger numbers. Furthermore, according to a description of Tacitus, the Germanic warriors used an iron sword, which was considered their most glorious weapon, in addition to the spear with a short narrow iron point and the shield. The shields were made of wood, covered with leather and decorated in bright colors, and a shield boss made of metal protected the sensitive central area. Usually the king led his troops into battle himself on horseback. Similarities can also be found in the names of the Rohirrim kings, such as "Théoden" or "Théodred", which are based on the Ostrogothic Theodoric , who commissioned the source used by Jordanes, the records of the Roman scholar Cassiodorus . Théoden also rides at the head of his troops for the liberation of the city of Minas Tirith, where he is killed.

- The Éorlingas or the people of Rohan

The people referred to as "Rohirrim" (horse people) in the story The Lord of the Rings show not only strong similarities with the Goths or Germanic equestrian peoples because of their external appearance, but also their origin from a country far north of Middle-earth was created similarly by Tolkien . The people originally called themselves “Éothéod” (horse people) in their own language and had settled in the headwaters of the Anduin (long flood) under King Earnil II. They were related to the "Beorningern" and the people from Rhovanion, a stretch of land south of the Bleak Forest. These people from Rhovanion were harassed by the people of the "wagon drivers" and driven to the outskirts of this forest. The kingdom of Gondor in the south was now attacked by a huge army of savage people in the year 2510 of the Third Age in Middle-earth. In this emergency the horse people came to their aid under their leader " Eorl the boy ". The attackers were able to be repulsed and as a thank you Eorl was awarded the territory "Calenardhon" (grassland, which was almost depopulated by a previously rampant plague ) of the Kingdom of Gondor as a settlement area. This area was henceforth called Rohan and was linked to the Kingdom of Gondor by an oath of allegiance. This parallel is found in the so-called Gotenvertrag from the year 382 and with Cirion oath and the alliance between the Rohirrim and Gondorianern.

Princely seats

- The wooden hall of the Mets

In the story about Beowulf there is the famous “ Heorot ” mead hall of the Danish King Hrothgar . This offers an ideal model for Tolkien's "Golden Hall Meduseld" (Old English: seat of the Mets), which resembles a Germanic or island Celtic "mansion". Such a hall consisted of a rectangular nave with walls made of wood or wickerwork coated with clay and often two load-bearing rows of wooden columns. Priskos , a late antique historian of the 5th century reports the following about the hall of the Hun prince Attila :

“In the middle of the steppe, the traveler came to a large settlement, where a stately courtyard rose, which is said to have been more magnificent than all the other houses of Attila. The building was made of beams, had walls made of panel wood and was surrounded by a wooden fence [...] "

The description of King Théodens Halle Meduseld in Edoras reads very similarly. Legolas says about the ruler's seat as they approach:

“A mound of earth and mighty walls and a hedge of thorns surround him. Inside are the roofs of houses; and in the middle stands the great hall of people on a green mountain saddle high above. And it seems to my eyes as if she has a golden roof. Its shine continues to shine across the land. The posts on their doors are also golden. There are men in shimmering armor [...] "

- Stone and marble halls

In Minas Tirith, on the other hand, the white stone capital of the Kingdom of Gondor in Middle-earth, a marble palace rises on the top level. The Lord of the Rings says about the throne hall: "[...] a silent group of large statues made of cold stone rose between the columns." Such figures are particularly known from Greek and Roman halls. In his story, Tolkien contrasts the historical contrasts of the richly decorated Germanic timber construction with the magnificent Roman stone buildings. Although wooden halls were built for a long time in the Germanic area, the Frankish-Carolingian rulers made their palaces out of stone based on the Roman model.

The buildings of the Romans in Great Britain

- Roman ruins

The poem The Ruin tells of a city of which only the ruined ruins can be seen. The former buildings were ascribed to the giants (enta geweorc - Ent means a giant in Old English and the tree herders in Tolkien). The poet describes it as follows: “[…] The builders and their human kingdoms - perished, perished and died. The protective wall also sank. Once upon a time there were bright houses, bathhouses, with high rooms in which the cheers of the people echoed as well as in some of the men's festival halls. [...] ".

Such ruins can also be found in Middle-earth, for example in the fallen kingdom of Arnor of the Númenorian immigrants. Their former royal cities Annúminas and Fornost Erain have long since disintegrated, as has the tower on the Wetterspitze, which once contained a palantír . Krause compares this with the buildings of the legionaries who invaded Britain and built their cities there based on the Roman model. After their departure they fell into disrepair, as the Anglo-Saxons did not have the same skills as the former occupiers. It is similar in Middle-earth, because the western people from Númenor were considered to be particularly skilled builders and they built roads and fortified cities in a way that normal people of Middle-earth could not do. Therefore the description of the poem would also apply to the kingdom of Arnor with its partial kingdoms Arthedain, Cardolan and Rhudaur. "[...] All of this has passed and the world has darkened. [...] ".

Like the Roman conquerors, the Númenórian builders also laid paved stone roads between their cities. These connected the kingdoms of Arnor and Gondor with one another. In particular, the north-south road between Annúminas in the north-west and Minas Tirith in the south-east, but also the Great Green Way, which connected the city of Fornost in the west past Bree with this road. There was also the Great East Road, which led from Annúminas to the Troll Heights and Rivendell, past the High Pass over the Nebelgebirge and through the Great Green Forest (Mirkwood, where it was called the Old Forest Road) to the banks of the River Eilend in the east. Harad Street finally led to the extreme south.

Industrial age and world wars

Tolkien lived at a time when, as a result of industrialization in Great Britain, many cities were characterized by factories with smoking chimneys and increasing environmental pollution, and which also had to survive two world wars. This influence is particularly evident in the story The Lord of the Rings through the way some areas are depicted.

- Desolated wastelands

In Tolkien's Middle-earth there are several areas hostile to life, such as Mordor or the Dead Marshes, the great desert of Harad or destroyed landscapes, such as the area around Isengard, areas destroyed by dragons on Erebor or in Beleriand, the north country inhabited by Melkor or the Helcaraxe. There are various models for such places in the old sagas, for example the land of the Fisher King in the Celtic tale of Parcival in Mabinogion or other Cymrian poems in which the respective hero has to cross these areas unscathed in order to fulfill his mission. In the Lord of the Rings this task falls to the hobbit Frodo and his loyal companion Sam.

A personal aspect of Tolkien's life comes into play here, as the depiction of the corpses in the water of the Dead Marshes is reminiscent of the fallen soldiers in flooded trenches from the warfare of the First World War , in which Tolkien participated. Isengard (Eisenstadt), on the other hand, illustrates Tolkien's criticism of the environmental degradation caused by the increasing industrialization of the city of Birmingham , where he spent part of his childhood. The Shire initially contrasts with this destruction, but is then also devastated by Saruman.

Geography and area names in Middle-earth

The maps that Tolkien developed for his work are similar to those that were used in medieval Europe. It is less about a real and precise representation of the actual locations and more about a symbolic representation of the historical or religiously significant places in the world known to Central Europeans at the time. These maps are grouped under the name Mappae mundi and are essentially limited to the continents of Europe, Africa and Asia. Tolkien also used this principle for his maps of Middle-earth. Tolkien even developed his own history of cartography in his mythology, for example the first map of Middle-earth (i Vene Kemen) still shows a ship shape. Only in the course of history do the maps become more detailed and precise, like the maps in the Hobbit or the Lord of the Rings, but also the maps of Beleriand or Númenors in the Silmarillion or the news from Middle-earth .

In particular, the numerous place and area names have a descriptive function, such as the Nebelgebirge, the Eilend River, the Wetterspitze or the Alte Straße. This form of naming is based on the Nordic sagas, which were conceived both as a historical report and as a literary work. Tolkien's use of place names and personal names is therefore almost unique in modern fiction.

- Middle-earth was the name given to the areas they inhabited by the Old Norse peoples. The name miðgarðr ( Midgard ) was common among the Teutons .

- The otherworldly realms (The Undying Lands) were called Ódainsakr by the Teutons and appear in the Eiríks saga viðförla . It is important in this context that Tolkien chose neither the Germanic nor the Christian conception of paradise on earth (the Garden of Eden or the residence of the gods is east of Europe) as the model for his Valinor, but rather from early medieval Irish texts and Celtic ideas according to which there were fabulous islands in the far west. These were also reported by early sailors, such as St. Brendan , who are said to be inaccessible to normal mortals. The same applies to the land of Aman, the seat of the Valar in Tolkien's world. Thus Aman with the dwelling Valinor can be compared with the Asgard and the Vanaheimr . With the Celts, the hereafter or the otherworld was also in the west. The old Icelanders called this island of the Blessed Hvitramannaland ( White Men 's Land) or Glæsisvellir (Glass Fields), as in the prehistoric saga Bósa saga ok Herrauðs . The Cymric term Avalon comes from the mythology of the Celts and plays an important role in the Arthurian legend . Tolkien used this term in a slightly modified form for the west and Valinor-oriented port of Avalóne (near Valinor) on the island of Tol Eressea (Lonely Island). The Silmarillion says “The Eldar [...] live on the island of Eressea; and there is a port called Avallóne, for of all cities it is the closest to Valinor, and the tower of Avallóne is the first thing the sailor sees when he finally approaches the lands of the immortals across the wide sea. "

- Landscapes and parts of the country

The areas of the Riddermark show particularly clearly a connection between this imaginary human race and Germanic ethnic groups. In Old Norse, fold means something like field or plain. Mark is an administrative district. Westernis (a name from Númenor) has the Scandinavian name element -ness, which means headland. It has similarities to the places Lyonesse or Logres the Arthurian legend on. Lyonesse has also sunk in the sea.

- Mountains, gorges and enchanted forests

The name of the Misty Mountains could be identical to the moist mountains (úrig fjöll yfir) from the Skírnismál. The name of the Rohirrim for Minas Tirith as Mundburg suggests a reference to the Old Norse name (Mundiafjöll) for the mountain range of the Alps. The name Ered Nimrais (White Mountains) is a direct translation of the Latin word albus as white. According to Simek , the gap of fate (Crack of Doom) probably has its origin in the Ginnungagap , the primordial gap, which played a decisive role in the creation of the world in Nordic mythology as a separating link between the hot ( Muspellsheim ) and cold pole ( Niflheim ).

The name of the large green forest, the “Mirkwood”, is clearly borrowed from Myrkviðr from Norse literature and Miriquidi from German medieval sources. The Tolkien Mirkwood (ne.) / Mirkwood, like the Myrkviðr from the Edda (exemplified in the Lokasenna ), separates the spiritual-mythical spheres, the world of humans from that of the gods (Edda) or the Elves and, as with Miriquidi, concrete settlement areas as topographical ones natural border. The latent threatening ductal of Mirkwood (DKH) shows similarities to eddischen events that are associated with the end of the world in connection (if the sons Muspells riding through the myrkviðr), which underlines the danger of the situation. The Norse literature describes this area as "Myrkvið in ókunna" (the unknown or impenetrable forest full of dangers), where the forest divides the country in the east between the Huns and the Goths . The model for this traditional term and the pronounced literary reception in Germania is the ancient Herkynische Wald .

The Roman historian Tacitus described the Germanic lands in the 1st century as "Terra etsi aliquanto specie differt, in universum tamen aut silvis horrida aut paludibus foeda" (Although the country differs considerably in shape, it is generally either rough in front Forests or hideous swamps).

Personal names of Nordic origin

The names of the dwarves were taken directly from the Edda by Tolkien. This creates a direct reference to Nordic mythology. This becomes particularly clear with the hobbit's dwarfs, who set off for Erebor with Bilbo. The names of many of these dwarfs can be found in a list in the Edda called Dvergatal , where it says:

“[…] Nyi and Nidi, Nordri and Sudri,

Austri and Westri, Althiof, Dwalin ,

Nar and Nain , Niping, Dain ,

Bifur, Bafur, Bömbur, Nori ;

Ann and Anarr, Ai, Miödwitnir.

Weig, Gandalf, Windalf, Thrain ,

Theck and Thorin , Thror , Witr and Litr,

Nar and Nyrad; now these dwarfs,

Regin and Raswid, are correctly listed.

Fili, Kili, Fundin , Nali,

Hepti, Wili, Hannar and Swior,

Billing, Bruni, Bild, Buri,

Frar, Hornbori, Frägr and Loni,

Aurwang, Jari, Eikinskjaldi . [...] "

Thorin Eichenschild is composed of two dwarf names. The name Gandalf is also listed here, which is not a contradiction, because it translates as magic album. Here Tolkien consciously worked with the speaking names, because they reflect the essence, a quality or the appearance of the person who wears them. Bombur means, for example, "the fat one", Gloin "the glowing one", which describes both his descent from the red-bearded fire dwarfs and his slightly quick-tempered disposition. Thorin is “the brave”, Thrain “the menacing” and Thrór “the prosperous”. One of the seven fathers of the dwarfs, who bears the name Durin, has a rather unusual name, because he can mean "the sleeper", "the sleepy one" or "the door guard". Tolkien wrote of him in the poem The world was beautiful in Durin's time :

“[…] Durin's people lived happily and sang,

Back then, when the harp sounded here,

And guards in front of the gates blew their horns

at every hour.

The world is now gray, the mountain is now old,

the chambers empty, the food cold,

no pimple digs, no hammer falls;

And darkness reigns in Durin's world.

In the deep shadow he now rests in

his tomb in Khazad-dûm.

Only the stars are still reflected,

In the lake where his crown is pale.

She rests there for a long time in the dark of night

Until Durin wakes up from sleep. "

This clearly shows that Tolkien, as one of the most important dwarfs of his mythology, gave him this name with care. Other dwarfs can be found in the prehistory to the Lord of the Rings, there the dwarf Mîm and his sons play an important role in the history of the children of Húrin . His figure is very similar to the story about the dwarfs Andwari and Hreidmar of Reginsmál in the Edda . Mîm's son is also killed, with Mîm keeping his own life in return. In the end he takes revenge by betraying Túrin, but is ultimately slain by Húrin. Many echoes from the Siegfried saga or the Nibelungenlied can be recognized in Túrin's story .

- Rohirrim and other human races

The names of the kings of the people of Rohan are a replica of the family tables of Anglo-Saxon royal families. Just like the names of their kingdom, they all come from the Old English-speaking area. Likewise, the names for the Ostlinge are provided with a typical Germanic ending -ling for their origin or descent. Also the hobbits, known as halflings, or the swertings (blacks) from the south. The advisor Théodens also has a Nordic name consisting of grima (mask) and wyrm-tunga (serpent's tongue). There is a well-known model for this name affix in the Gunnlaugr Ormstungas saga .

European figures of gods

In addition to the Germanic ideas of gods, the Ainur (Valar and Maiar) created by Tolkien have various similarities to the Greek or Roman gods. The Valar borrowed some attributes from the gods of Olympus from Greek mythology . Like the Olympian gods, the Valar live on a high mountain separated from mortal people. Echoes of Poseidon can be found in Tolkien's figure Ulmo (the Vala of the water) and Zeus corresponds in his position to the Vala Manwe, as lord of the air and king of the Valar. The god families consist of twelve members each. With the Romans, these were especially Jupiter and Neptune . In the Silmarillion, however, a number of 14 is given for the gender of the gods. “The great spirits call the Elves the Valar, the powers of Arda, and people have often called them the gods. The princes of the Valar are seven, and the Valiër, the princesses, also seven. "

Odin's traits (Óðinn in Old Norse) appear in Tolkien's work in several people. On the one hand he is embodied by the magicians Gandalf and Saruman in his external appearance, on the other hand Sauron and the highest Valar Manwe also show clear characteristics of the Germanic god. Odin's appearance is described in the Völsunga saga as follows:

"And when the fight had lasted for a while, there came a man into the battle, with a hat that drooped for a long time and a blue coat, he had only one eye and was carrying a spear in his hand."

"The next day Sigurd went into the forest and met an old man with a long beard who was unknown to him."

Similarly, Gandalf is described in The Hobbit when he first appears at Bilbo's door. "All that [...] Bilbo saw that morning was an old man with a staff, a tall, pointed blue hat, a long gray coat, with a silver sash over which his long white beard hung [...]."

Gandalf and Saruman show some of the magical abilities of Odin, with Gandalf devoting himself more to spells (galdrar) and Saruman using the black art (seiðr), of which Snorri Sturluson says in Heimskringla, Ynglinga saga , chapter 7: "[...] with it he could learn the fate of people and future things, bring people death, misfortune or illness, and rob people of their minds or their strength [...]. ”Tolkien has this magical influence on Théoden's apparent illness, that of Grima, as a henchman Saruman's evoked, implemented. Gandalf owns the fastest horse (Shadowfax, Schattenfell) like Odin the eight-legged stallion Sleipnir . Both horses have a gray coat and Tolkien himself described the horse as follows: "Sceadu-faex, having shadow-gray mane and coat." (Sceadu-faex, had shadow-gray mane and coat). The element -fax can also be found in the name of Freyr's horse Freyfaxi in the Icelandic Hrafnkels saga or in the Edda for the horses Skinfaxi and Hrimfaxi (shimmer mane and frost mane), which in the Vafþrúðnismál draw day or night.

Odin is repeatedly described as an old wanderer who suddenly appears for the benefit of the people and gives them helpful advice. This also applies to the character of Gandalf. Another aspect is Odin's ability to change shape. For example, on the run from the giant Suttungr, he turns into an eagle in order to escape. Tolkien used this detail in a modified form by letting Gandalf escape from the Orthanc on an eagle .

Both sorcerers have great wisdom, which is also an attribute of Odin. Saruman is also considered a skilled speaker who is able to influence his audience with words. Like Odin, Saruman also uses ravens as conveyors of information, so that the Orthanc, with the palantir in it, has similarities with Odin's high seat Hlidskialf and his ravens Hugin and Munin .

Like Gandalf and Saruman, Sauron is one of the Maiar and this figure clearly shows the dark characteristics of the German god. Sauron was initially considered to be particularly handsome, which is a first sign of shape change, later he has to change his appearance, can only appear to people with a repulsive appearance or takes the form of the lidless eye on the Barad-dûr (Odin was one-eyed) . This element can be found even more strongly in the Silmarillion, in Sauron's fight with the dog Huan, where the reference to Odin's wolves also comes to light.

“Hence he [Sauron] took the form of a werewolf, the most powerful that has ever set foot on earth. [...] But no magic bite, no witch's verse, no poison, no claw, no devil's art, no fiend strength could defeat Huan from Valinor; and he took the enemy by the throat and crushed him. Now Sauron changed form, from wolf to snake and from monster to its true form; […] And immediately he took the form of a vampire, as big as a dark cloud in front of the moon, and fled with blood dripping from his throat, and he flew to Taur-nu-Fuin and dwelt there, filling the land with horrors . "

This description is similar to a description of the last fight between Odin and the Fenriswolf in the Ragnarök , where Odin is devoured by the wolf, but Sauron is only grabbed by the throat and thrown to the ground by Huan.

Snorri Sturluson describes Odin's abilities very similarly:

“Odin could change shape. His body lay there as if asleep or dead, but he was a bird or an animal, a fish or a snake, and in moments he went to other countries, in his own affairs or those of other people. [...] He always had Mímir's head with him, and this told him a lot of news from the other world, [...] He had two ravens that he had tamed with language. "

The Valar as a family of gods in Tolkien's mythology have many similarities with the Germanic family of gods in their properties and representation. Manwe, as the highest of the Valar, can be compared with Odin, who is often referred to by Snorri Sturluson as "the highest and oldest of the Aesir". Manwe also holds this position. “[…] The mightiest among those Ainur who entered the world was Melkor in the beginning; Manwe, however, is Ilúvatar dearest and most clearly understands his intentions. For the duration of the time he was made the first of all kings: the prince of the kingdom of Arda and ruler of all that lives there. […] “Tolkien confirmed this in the Book of Lost Stories . There it says: “[…] It then goes on to say that Eriol told the fairies [Elves] of Wôden, þunor, Tiw etc. (these are the old English names of the Germanic gods Odin, Thor and Tyr ), and they identified them with Manweg , Tulkas and a third god whose name cannot be deciphered. ”Odin and Manwe both have great wisdom and birds (with Manwe it is eagles) that carry information to them. The art of poetry attributed to Odin is practiced by Tolkien in Manwe through his love of music, but also mentions rather casually that the Vanyar learned both singing and poetry from him, because poetry delights Manwe and sung words are music to him. Like Odin, Manwe also has a high seat in the Taniquetil and from there overlooks the world.

Snorri Sturluson tells of the three Norns Urðr (origin, fate, the past), Skuld (guilt, what should be / will be, the future) and Verdandi (becoming, the now), these are the ones in Norse mythology who do this Assign fate. The Norns come to every newborn human child and determine both the length of its life and the path it will take. These ideas can be found in numerous skald poems or the songs of gods and heroes in the Edda. The Germanic generic term that describes this is the Wurd (skill, fate), which became Urðr in the Nordic world.

In Tolkien's mythology there are also corresponding figures, for example the Vala Námo (herald, judge) with his hall Mandos, who gathered the deceased there and determined their fate after death (rebirth among the Elves, ride on the Ship Mornië to the far north with the people). Whoever was called in Námos Hall had lost his life in Middle-earth through violent death (elves, humans) or death through aging (humans). Next to him is Vaire Serinde (knotter, weaver), the Valië of the past and the weaver of fate, who pulls the strings in her hand. It is comparable to Fortuna , Tyche or Verdandi, who can see into the future. Also on this one Fui Nienna (the sad, pitiful), the sister of Námo and Irmo, but was also responsible for sorrow and pity for cold and frost. She had the power to give consolation and alleviate suffering. Her title "Fui" stands for darkness and night. Gandalf lived with Irmo the dream-giver and his wife Estë (the healer) under the name Olórin (dreamer) before he left for Middle-earth. In this way he could bring advice to people in need and influence the fate of Middle-earth for the better. The gift of foresight also plays an important role in Middle-earth, which is comparable to the prophecies or oracles of antiquity. The fact that prophecies had their firm place in mythology is also shown by the Völuspá , in which a seer predicts future events ( Ragnarök ). This influencing of fate pervades the history of Middle-earth almost imperceptibly. This is particularly evident in the example of the children of Húrin . Túrin is nicknamed Turambar (Master of Fate). The farewell words of his sister Niënor also testify to the power of this influence: “Farewell, O twice beloved! A Túrin Turambar turin 'ambartanen: master of fate, mastered by fate! Oh luck to be dead! ”Then she throws herself into a ravine. As one of the few people, however, Túrin is to be granted a rebirth for the “battle of battles” (parable to Ragnarök), where he is to decide this as master of fate by killing Melkor for good .

Along with Odin, Thor is one of the most important deities in Germanic mythology. He is known as the protector of Midgard and through his magical hammer Mjölnir (this was created by the two dwarves Sindri and Brokk), with which he is supposed to fight the Midgard serpent in the final battle . In the case of the Vala Aule , also created by Tolkien as a blacksmith, it is the creation of stars by sparks that the latter strikes with his hammer (similar to Thor's lightning bolts) that are important for the history of Middle-earth. Aule is considered to be the father of the dwarfs, so has a relationship with them too. The name Aʒûléz (in the language of the Valar), particularly mentioned by Tolkien, is similar to the Germanic Þunaraz for Thor. Both figures have a hammer as well as an anvil.

Christian influences

The Bible and traditional Christian narratives show some correspondences in the complete works on Middle-earth. This is particularly evident in the Silmarillion . Tolkien was a devout Catholic . The conflict between Melkor and Eru Ilúvatar shows visible parallels to the depictions of Lucifer's rebellion against God and the fall from heaven . The evil of the world is personified in the figures and names of the devil and a multitude of evil creatures and demons. Melkor and some of his creatures or helpers had names that sounded very similar to those used to designate the devil. (Melkor / Belurth to Beelzebub , Sauron to Satan , Tevildo to the devil, with Tolkien replacing the cat king Tevildo from the story of Lúthien and Beren later in the Silmarillion with the Maia Sauron). In addition to extensive work in the field of Norse mythology, Tolkien, as professor of philology at Oxford University, was also entrusted with Bible translations. One of his most important works in this context is his collaboration in the creation of the Jerusalem Bible after the Second Vatican Council . Accordingly, place names in his works, for example the fictional continent Middle-earth, have counterparts to biblical names such as En Dor .

Further parallels can be seen in the biblical fratricide ( Cain and Abel ) and the fall of man with the expulsion from the paradise of Genesis and the killing of the kin and the exile of the Elves from Valinor.

The creation story of mythology in Middle-earth begins similarly to the Bible and also has a monotheistic God as its creator.

“In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. And the earth was desolate and empty, and it was dark on the deep; and the Spirit of God floated on the water. And God said: Let there be light! and there was light. And God saw that the light was good. Then God separated the light from the darkness and called the light day and the darkness night. [...] "

“Eru was there, the one who is called Ilúvatar in Arda; and first he created the Ainur, the saints, offspring of his thoughts; […] But when they had come into the void, Ilúvatar said to them: “See, this is your song!” And he showed them a vision [vision] and gave them to see what they had only heard before; They saw a new world, and it arched itself in the void and was carried by the void, but it was not like you […] And suddenly the Ainur saw a light in the distance, like from a cloud with a flame in its heart; and they knew that this was not just a face, but that Ilúvatar had created a new one: Ea, the world that is. "

Holger Vos quotes in his book The Interpretation of the World in the “Silmarillion” by JRR Tolkien Mark Eddy Smith, who wrote: “Tolkien copied the Bible with his work, but he did not want to replace it, but to support it.” Or Martin J. Meyer, der said: "So Tolkien is undoubtedly a religious sub-creator of Middle-earth [...]".

Mythological elements - imaginary beings

Nature spirits

A character in Tolkien's work that is difficult to classify is Tom Bombadil. A mythological model is not recognizable and Tolkien himself said of him: “[…] there must be enigmas, which are always there; Tom Bombadil is one of them (on purpose). ”Tom Bombadil can, however, be seen as a personification of the original nature, because his wife Goldberry says of him:“ He is as you have seen him, [...] he is the master of forest, water and mountain. [...] He has no fear. Tom Bombadil is the master. ”He says of himself:“ I am the oldest. […] Tom was here in front of the river and the trees; Tom remembers the first raindrop and the first acorn. "He has a corresponding name among the peoples of Middle-earth, the Elves call him" Iarwain Ben-adar "(the oldest without a father), the dwarves called him" Forn ", a Scandinavian name for old, prehistoric, with the northerners it was called "Orald", which means very old or very old in Old English. In Norse mythology there are giants with a similar name Fornjótr who are among the oldest beings. His nature also shows features of the wild or the green man , which are known from medieval texts or representations.

Ents also belong in this category of natural forces, although Tolkien wrote of them: “[...] that the Ents consist of philology, literature and life. They owe their name to the Old English "eald enta geweorc" and their relationship to stone. "These beings are mentioned in the poems The Wanderer and The Ruin as well as in Beowulf . They denote an ancient generation of giants who, according to the early medieval conception, had created monumental buildings or streets, but died out. The Ents' relationship with their wives has echoes of Njörðr and Skaði . Treebeard's song about Entfrauen suggests a similar incompatibility of their demands on their preferred living space. Another inherited feature is the Entthing, the council meeting of the Ents, which was held according to the rules of the Germanic Thing . Tolkien also uses the unusually monotonous and word-repeating language (Entish) of these creatures to illustrate the lengthy process of finding an opinion and reaching agreement in such an assembly. As an example, one of the few words from this language: "Taurelilómea-tumbalemorna Tumbaletaurea Lómeanor" would be the abbreviation for the Fangorn forest , translated it means "forest much shaded - deep valley black deep valley forested night darkness home".

Beorn, the shapeshifter , was influenced by the stories about Beowulf. The name Beorn (bear but also man) refers to the wild berserkers or Odins warriors, who wrapped themselves in bear skins and developed enormous powers in a state of intoxication, like Beorn when he entered the "Battle of the Five Armies" at the end of the Hobbit . The translation of the name Beowulf (bee-wolf) also corresponds to the old English Beorn, as a honey-loving bear. Influences on this figure can also be assumed in the Egils saga , because Beorn's son Grimmbeorn (Grim Bear) has a similar name to Egil's father Grímr Kveldúlfsson (Kveldúlfr = evening wolf). Another story about the nocturnal transformation of a man into a bear is Bjöthvarr Bjarki in the Hrolf Krakis saga , who is doomed to behave as a bear at night. Beorn, too, only turns into a bear at night, while as a human he breeds bees during the day. The Beorns hall sketched by Tolkien corresponds to a description from Beowulf , which corresponds to the illustration of an Icelandic hall from the year 1000.

Friendly creatures from mythology

- Hobbits

According to Tolkien, the hobbits came from an inspiration he wrote on a blank sheet of paper while correcting his students' exams. "In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit" (In a cavity in the ground there lived a hobbit). They do not originate from European mythology and Tolkien himself derives their name from an unrecognized Old English word hol-bytla (cave dweller). Due to the similarity with the English word for rabbit (rabbit) it is reasonable to assume that Tolkien incorporated this into the conception of their living space, but he says clearly: “My hobbit [...] was not hairy, except on his feet. He still resembled a rabbit. He was a well-to-do, well-fed bachelor by his own means. […]. ”Nevertheless, the hobbits show similarities to mythological beings such as brownies, goblins or goblins, which like these have only rarely been seen by a human.

However, the hobbits are already mentioned in a list of mythical creatures in The Denham Tracts (between 1846 and 1859 by Michael Aislabie Denham ). That list is based on an older list from Discoverie of Witchcraft , dated 1584. The Tracts were later revised by James Hardy for the Folklore Society and printed in two volumes in 1892 and 1895.

- Dwarfs

The dwarves, on the other hand, show clear echoes of the ideas of Old Norse mythology. But it was important to Tolkien that they are not intended to be completely identical to these. He makes this clear through the changed spelling for his dwarfs in Middle-earth (dwarves) compared to the dwarfs of the Liederedda (English dwarfs). As a philologist, he chose this spelling from the presumed historical form dwarrows and because "dwarves" is more harmonious in terms of sound with "elves" (elves). But there are clearly more similarities between the dwarves of tradition and those from Middle-earth than differences. They are described in the Edda as follows:

“[…] The dwarfs had formed first and came to life like maggots in the flesh of the giant Ymirs . But by the decision of the gods they were given intellectual wisdom and human form. Yet they live in the earth and in rocks. Modsognir was the highest and Durinn the second. "

Tolkien also mentions Durin as one of the seven fathers of the dwarfs. Their formation from the element earth is also described in the Silmarillion, when the Valar Aule created them as children of his own imagination, even before the first children (elves) of Ilúvatar (the creator) woke up on Arda. When Ilúvatar learns about it, he lets these beings come to life, but on the condition that they must rest underground until his own creatures would one day appear.