Little Red Riding Hood

Red Riding Hood (even Little Red Riding Hood and the (evil) Wolf , in Burgenland, Austria and Hungary also Piroschka from Hungarian piros : red) is a European fairy tale type ATU 333. It is in the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm as Little Red Riding Hood in place 26 (KHM 26) and goes back verbally through Johanna and Marie Hassenpflug to Charles Perrault's Le Petit Chaperon rouge in Contes de ma Mère l'Oye (1695/1697). Ludwig Bechstein took over the fairy tale in 1853 from the Brothers Grimm in his German fairy tale book as Das Rotkäppchen (No. 9).

Lore

The first two literary versions of Little Red Riding Hood were written by Charles Perrault in 1695 (Perrault's Tales of the Mother Goose, The Dedication Manuscript of 1695 , Ed. Jacques Barchilon, 2 volumes, New York 1956, The Pierpont Morgan Library) and 1697 ( Contes de Perrault , Paris 1697, facsimile print, Ed. Jacques Barchilon, Geneva 1980). The Brothers Grimm published the story in the first volume of their Children's and Household Tales from 1812 under the number 26. Little Red Riding Hood is one of the most frequently edited, interpreted and parodied fairy tales.

content

A little girl, Little Red Riding Hood, to whom her grandmother once gave a red cap, is sent by her mother to bring her bedridden, sick grandmother, who lives in a house in the forest, a basket of goodies (cake and wine). The mother urgently warns Little Red Riding Hood not to stray from the path. In the forest you can have a conversation with a wolf. He listens to Little Red Riding Hood and draws her attention to the beautiful flowers in a nearby meadow, whereupon Little Red Riding Hood decides to pick another bouquet, despite her mother's warning. The wolf rushes straight to the grandmother and eats her. He lies down in her bed in her nightgown and waits for Little Red Riding Hood. Soon after Little Red Riding Hood reached the house, enters, and goes in (with Perrault) or to (the Brothers Grimm) Grandmother's bed. There Little Red Riding Hood is amazed at the figure of his grandmother, but does not recognize the wolf before it is also eaten. At Perrault, the fairy tale ends here.

Grandmother and Little Red Riding Hood are freed from the wolf's belly by the Brothers Grimm, and stones are put into the wolf's belly instead. Because of the weight of the stones, the wolf cannot escape and dies. In an Italian version, The False Grandmother , Little Red Riding Hood breaks free through his own cunning and flees. The wolf then dies.

interpretation

The fairy tale of Little Red Riding Hood and the Big Bad Wolf can be interpreted in such a way that it is intended to warn young girls against attacks by violent men. The moral at the end of the fairy tale in Perrault's version is:

“Children, especially attractive, well-behaved young women, should never talk to strangers, as they could very well be giving a wolf's meal if they did. I say “wolf”, but there are different kinds of wolves. There are those who chase after young women at home and on the street in a charming, calm, polite, humble, agreeable and warm manner. Unfortunately, it is precisely these wolves that are the most dangerous of all. "

According to the psychoanalyst Bruno Bettelheim , this fairy tale is about the contradiction between the pleasure and reality principle. Little Red Riding Hood is like a child who is already grappling with puberty problems but has not come to terms with the oedipal conflicts. It uses its senses. This creates the risk of being seduced. In contrast to Hansel and Gretel , where the house and forest house are also identical, mother and grandmother have shrunk to insignificance here, but the male principle is split into wolf and hunter.

For the psychiatrist Wolfdietrich Siegmund , the fairy tale encourages perseverance where you cannot free yourself even though you are not to blame. That is important for depressed people. It is questionable when Little Red Riding Hood in a modern version has a knife with her and cuts open her stomach from the inside. Homeopaths compared the fairy tale to the medicines Belladonna , Lycopodium , Drosera and Tuberculinum . The neurologist Manfred Spitzer thinks that Little Red Riding Hood stays healthier than the stressed wolf because it doesn't experience the loss of control that way.

Little Red Riding Hood - origins and development

The fairy tale Little Red Riding Hood is one of the most famous stories in Europe. In the course of time, history has changed in various ways, it has been told and reinterpreted over and over again and always suggested new moral statements. The text was also completely changed, expanded, used, parodied and used as a satirical mask for completely different communication purposes several times. There were versions that moved the main character from the forest into a new environment and invented a fundamentally new plot. In the following, the development of the story will be made clear using a few selected examples.

Emergence

The story of the little naive girl who is duped by the wolf and how her grandmother is finally eaten was originally a folk tradition that was passed on orally from generation to generation. Therefore, it is not possible to determine an exact time of origin.

According to a theory developed by the Italian Anselmo Calvetti , the story may have been told for the first time in early human history. She could process experiences that people made during an initiation rite to join the tribal clan. Here they were symbolically devoured by a monster (the totem animal of the clan), had to endure physical pain and cannibalism in order to finally be “reborn” and thus be considered as adult members of the tribe.

This cannibalism reappears in some Rotkäppchen versions. Hungry Little Red Riding Hood eats her grandmother's meat and drinks her blood without knowing it. The use of the wolf as an evil force could stem from people's fear of werewolves . In the 16th and 17th centuries in particular, there were numerous trials , similar to the witch hunts, in which men were accused of being werewolves and of having eaten children.

Individual motifs of the version known today can be traced back a long way. For example, there is the myth of Kronos devouring his own children. When Rhea was pregnant with Zeus and was tired of her husband devouring her children, she wrapped a stone in diapers and gave it to Kronos instead of Zeus. Zeus later freed his siblings and the stone from his father's belly. In the collection of sayings and stories, Fecunda ratis , which Egbert von Lüttich wrote around 1023, there is the story of a little girl who is found in the company of wolves and who has a red piece of clothing.

The Brothers Grimm, who changed and added to the individual texts of their children's and house fairy tales (first in 1812) over several decades until the last edition of 1857 in the sense of adapting them to their own intentions as well as to the fashions of the time, some even removed , also wrote constantly changing comments on the fairy tales from the beginning. In the original edition from 1812, Little Red Riding Hood came out almost completely empty, there is only the note that this fairy tale was "nowhere to be found except in Perrault (chaperon rouge), after which Teck's adaptation".

However, the first volume of the original version of the KHM contains a variant of the fairy tale that follows the usual version of the fairy tale. Little Red Riding Hood is not distracted by the wolf, goes straight to the grandmother and tells her about the encounter. They lock the house and don't open it to the wolf when he knocks. At the end he climbs up on the roof to watch the girl. Grandmother now lets Little Red Riding Hood pour the water she used to cook sausages the day before into a stone trough in front of the house, the scent fills the wolf's nose, who slips off the roof with greed and drowns in the stone trough.

The commentary on the fairy tale changes in the second edition of 1819. Now the following reference appears: “In a Swedish folk song (Folkvisor 3, 68, 69) Jungfrun i Blåskagen (Black Forest) [we encounter] a related legend. A girl is supposed to keep watch over a corpse across field. The path leads through a dark forest, where he meets the gray wolf, 'oh dear wolf,' it says, 'don't bite me, I'll give you my silk-sewn shirt.' "I don't ask for your silk-sewn shirt, your young life and blood I want to have<. So she offers him her silver shoes, then the gold crown, but in vain. In distress, the girl climbs a high oak: the wolf is digging up the roots. The maiden in agony gives a piercing cry; her lover hears it, saddles up, and rides as fast as a bird as he comes to the spot (if the oak is overturned, and) there is only one bloody arm of the girl left. "

Charles Perrault's petit chaperon rouge

One of the oldest known written versions comes from the French Charles Perrault and was published in 1697 under the title Le petit chaperon rouge . Since the story was intended for reading at the French court of Versailles , Perrault largely avoided elements that could be considered vulgar (e.g. cannibalism). The story doesn't end well with him, the grandmother and Little Red Riding Hood are eaten by the wolf without being rescued afterwards. Perrault writes less a fairy tale than a moral deterrent parable. In his version there are numerous allusions to sexuality (so when asked, Little Red Riding Hood lies naked with the wolf in bed). At the end there is also a little poem that warns little girls about morons. Perrault intended to explicitly lay down rules of conduct with the narrative, and in doing so he resorted to deterrence.

Of course, Perrault's fairy tale has also been translated into other languages, for example it is known in England under the title Little Red Riding Hood . Perrault's fairy tale was translated into English by Robert Samber as early as 1729 and published in the same year. A happy ending to the Perrault version, however, only occurs, falsifying the original, in Moritz Hartmann's ironic translation of the Perrault fairy tales into German in 1867; the happy ending of the fairy tale had been standard in German-speaking countries for over half a century.

First German versions

The first German translation of the French Le Petit Chaperon Rouge appeared in 1760/61. However, since the upper classes of society were largely able to speak French, the story was likely to have spread in German-speaking countries before then.

The version that appeared in the first volume of Children's and Household Tales by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in 1812 has a happy ending, a fairy tale ending. A hunter rescues Little Red Riding Hood and his grandmother from the wolf's belly and instead fills it with stones, which leads to the death of the animal. This ending is borrowed from another fairy tale that the Brothers Grimm also wrote down: The Wolf and the Seven Young Goats . A similar devouring motif also appears in the fairy tale made almond tree .

In the same issue, the authors published another kind of sequel in which the girl meets a wolf again. This time it proves that it has learned from the previous experience and alerts the grandmother. With combined forces, the two manage to outsmart the animal, which, like its predecessor, eventually dies. The fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm goes back in part to a retelling by Johanna Hassenpflug (1791–1860), called <Jeanette> (the sequel version goes back to Marie Hassenpflug). Their stories are the sources for several fairy tales in the brothers' collection. In addition, they went back to the first time in 1800 published dramatic editing tragedy of the life and death of small Roth coping by Ludwig Tieck that arose based on Perrault's story. Thus, the Grimm fairy tale indirectly has Perrault as a model. However, the brothers cleaned the original version of what they thought were too cruel, too sexual and too tragic components and thus adapted it to the demands of the rising middle class in the 19th century .

Tieck's treatment of the Little Red Riding Hood material comes from a time of great unrest: The events of the French Revolution spread their influence to Germany and were welcomed by many intellectuals. After Napoleon came to power , the enthusiasm for the revolutionary ideals soon changed to great disappointment with the imperial aspirations of the French emperor. Tieck - himself initially a supporter of the Jacobins - probably processed the disappointment over the betrayal of the revolution leading to the establishment of the French Empire in his literary work, including in the Little Red Riding Hood fairy tale.

19th century

In the further course of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the structure of the fairy tale remained largely unchanged, but some authors also removed the few remaining scenes of violence (e.g. the devouring Little Red Riding Hood) and places with a sexual undertone that they did felt to be too raw. Mostly Little Red Riding Hood remained in her naive and helpless position and was rescued by the male hunter, which reflects the image of women of the time. In 19th century Germany, fairy tales became increasingly cuter and Christian to make them more accessible to children. The Brothers Grimm themselves revised their own fairy tales several times until the wolf became an old sinner in 1857 . In 1853 Ludwig Bechstein included Little Red Riding Hood in his German fairy tale book , using the Grimm version as a template. He tried to make his version funnier and more popular, but his artificial style easily got lost in childishness. Bechstein never appeared as a competitor to the fairy tale brothers.

In March 1826 Eduard Mörike wrote a poem called Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf . Here the wolf regrets what he did and hopes that one day the dead girl will be able to forgive him. Further versions were created by Gustav Holting (1840), who also used the motif of the sinful wolf, Moritz Hartmann in his translation Perraults (1867), where he changed the ending, and Ernst Siewert (1880). Interestingly, in contrast to the French versions, erotic elements rarely appear in the German arrangements ; instead, great emphasis was placed on calm and order.

Alexander von Ungern-Sternberg, on the other hand, portrayed Little Red Riding Hood in 1850 rather funny and parodied Biedermeier behavior. In 1907 Anna Costenoble published the book Ein Frauenbrevier for hours hostile to men , in which she deals with the ridiculous morals of the German upper class in a Little Red Riding Hood parody. A large number of adaptations were made in France, for example the opera Le petit chaperon rouge with the music by François-Adrien Boieldieu and the text by Marie EGM Théaulon de Lambert . This is a very sentimental piece of music that was spread in France and Germany, but also in England and America. However, it has only marginally to do with Little Red Riding Hood . 1862 wrote Alphonse Daudet with Le Roman du chaperon rouge a work in which Little Red Riding Hood, the bourgeois norms of society rejects, it is a symbol of protest, but must eventually die. The fairy tale was so well known and present at this time that it was an important part of raising children in all social classes. The aspect of obedience was particularly emphasized in the numerous versions, drawings and picture sheets ( Charles Marelle : Véritable Histoire du Petit Chaperon d'Or , The true story of the gold cap , 1888).

Another version was provided by Pierre Cami in 1914 with his short piece Le petit chaperon vert ( Das Grünkäppchen ). The parents of Grünkäppchen are represented here as absurd figures, while the girl herself is characterized by independence and cunning. She manages to save herself with the help of word games by not delivering the right questions in that famous question-and-answer dialogue ("Eh, grandmother, what big ears you have") and thus upsetting the wolf, that he finally leaves the house with the words: "Oh, where are the naive children from before who were so easily eaten!" This type of parody became particularly popular after World War I , when the role of women also changed significantly. There were also numerous adaptations in English, a few of which were also parodic in nature, such as "The true historie of little red riding hood or the lamb in wolf's clothing" (1872) by Alfred Mills , who used the story to learn about to make fun of the current politics of the day. Little Red Riding Hood was used in advertising as early as 1890 : Schultz and Company used it in their STAR soap advertising. There were two components to this:

Moral I: If you want to be safe in this world / from danger, strife and worry, / be careful with who you get involved with / and how and when and where. Moral II: And you should always be clean / and happy, never moping, / to achieve both, my child, you / always have to take our STAR soap "

From naive to independent Little Red Riding Hood

In the 20th century, Little Red Riding Hood became increasingly funny, rebellious and also more realistic. It is noteworthy that many versions with their ironic elements were primarily intended for adults.

In 1923, during the Weimar Republic , a phase of literary experimentation, also with regard to fairy tales, a strongly satirical version was created in which traditional child rearing and ideas of sexuality were questioned: Joachim Ringelnatz wrote Kuttel Daddeldu tells his children the fairy tale of Little Red Riding Hood . Neither Little Red Riding Hood himself nor the audience / readers are treated too gently here. The narrator identifies with the grandmother, who in the course of the fairy tale begins to devour everything that comes within her reach.

Werner von Bülow, on the other hand, interpreted "Little Red Riding Hood" in the 1920s in an extremely racist and exaggeratedly nationalist way and even saw parallels to the stab in the back legend . His essay was published by the Hakenkreuz-Verlag. During this time there were numerous attempts to trace all Grimm fairy tales back to German origins, which was quite hopeless, as many come from France or other European countries.

However, there were also attempts to counter the Nazi propaganda. In 1937 an anonymous version appeared in the Münchner Neuesten Nachrichten , which is reproduced here as a facsimile.

In 1939 the New York humorist James Thurber published his story The Little Girl and the Wolf , at the end of which Little Red Riding Hood draws a pistol and shoots the wolf. With Thurber's morals - little girls are no longer so easily fooled these days - the original characters began to turn into their opposite. After 1945, numerous parodies followed, such as Catherine Storr's little Pollykäppchen (in the volume Clever Polly and the Stupid Wolf , 1955). The clever and fearless Polly tricked the stupid and conceited wolf time and time again without needing the help of others. But there were also more serious adaptations that usually portray the girl with more confidence, including versions by feminist authors. From time to time Little Red Riding Hood was also associated with communism and designed accordingly. The common basic idea can be recognized: Little Red Riding Hood is no longer innocent, well-behaved and helpless, but intelligent and quite able to help herself.

In some versions, the wolf is no longer portrayed as an evil character, but as a misunderstood figure who basically just wants to be left in peace, as in Philippe Dumas ' and Boris Moissard's blue skullcaps . Thaddäus Troll wrote a parody of official German. He also added slogans to the plot. This is also supposed to point to the subject of seduction. When Anneliese Meinert 's mother has an appointment, so Little Red Riding Hood is racing with 180 on Wolf over to tricked-grandma ( "... why do you have such bright eyes?" ... "contact lenses" ), but expects "a bridge party." Little Red Riding Hood's hunter friend gets cake and whiskey. Rudolf Otto Wiemer's Wolf trivializes the story in retrospect, and Little Red Riding Hood, intimidated, agrees. With Max von der Grün's red cap with the white star, everyone suddenly envies and hates them until they lose them. At Peter Rühmkorf 's, Little Red Riding Hood nibbles on cake and wine and takes off the wolf's fur in the hut until Grandma intervenes. With his poem Little Red Riding Hood (1982), Roald Dahl tried to encourage readers to break away from traditional fairy tale reception and find new approaches. In the text Little Red Riding Hood asks questions about the beautiful fur of the wolf. When the angry wolf finally wants to eat her, she shoots him with a pistol and then proudly carries his fur around the forest. Janosch's little electric little red riding hood contains the word electric in every sentence , so the electric wolf seduces him to look at electric lamps and finally the electrician rescues him. Sławomir Mrożek's bored Little Red Riding Hood fantasizes about a wolf and is actually suppressed by her grandmother. Even Günter Grass takes in The Rat Red Riding Hood and the Wolf, and take in this novel fairytale characters the power to cause confusion and save the world after all. Another parody can be found in Paul Maars The Day Aunt Marga Disappeared and other stories . Little Red Riding Hood also appears in Kaori Yuki's manga Ludwig Revolution . Michael Freidank tells the story in Gossend German. Parodies by Andreas Jungwirth , Katharina Krasemann and Klaus Stadtmüller appeared in Die Horen . Karen Duve turns it into a werewolf story.

Otto Waalkes made a sketch of Little Red Riding Hood and also had it appear in his film 7 Dwarfs - Men Alone in the Forest . The film Die Zeit der Wolfe processes the motif in a fantasy / horror interpretation, while the Japanese anime film Jin-Roh weaves the symbolism of the fairy tale into an anti-fascist and violence-critical background story. In 2004, the processed French singer Zazie the story of Little Red Riding Hood in the song Toc Toc Toc , in which they - in all likelihood - their own development from a small girl, the fear gets inspiring story of Little Red Riding Hood, the way to woman in search of the - possibly no longer existing - prince, actually waiting to be eaten by the wolf . Ringelnatz award winner Achim Amme has been traveling the country for years with the humorous live program Rotkäppchen & Co. and published a Rotkäppchen-Blues in his book Ammes Märchen (2012). A demonstration poster on television pictures from the time of reunification often shown shows Egon Krenz 's face and “Grandmother, why do you have such big teeth?”.

In addition to the numerous parodies of the fairy tale, in which there is a role reversal between the main characters, there are countless travesties that translate the fairy tale into dialects or another register of the language: Little Red Riding Hood in Bavarian , but also completely serious in the official languages of the EU. Then on linguistic, on mathematical, in the GDR, in the scene, Little Red Riding Hood and psychoanalysis, the evil interpreters. Especially the grandmother's dialogue “Why do you have such big eyes” etc. is often quoted. In summary, it can be said that the reception of fairy tales has changed continuously over time and with reference to social developments such as the rise of the bourgeoisie in the 19th century or the emancipation of women in the 20th century. Nevertheless, the Grimm fairy tale version is still best known in Germany today.

The National Rifle Association has developed its own fairytale story in which Little Red Riding Hood unlocks a gun. "Oh, how the wolf hated it when families learned to defend themselves," wrote Amelia Hamilton, trying to get children to join the NRA.

Cultural-historical transformations

The story of Little Red Riding Hood has inspired numerous dramas, operas and a number of works of fine art , above all hundreds of illustration suites in fairy tale books of all kinds and films . A silhouette in Henri Matisse 's Jazz series depicts Little Red Riding Hood.

Theater and puppet versions

- Robert Bürkner : Little Red Riding Hood as a play for children and adults (1919)

- Christel and Gerard Mereau: Little Red Riding Hood as a puppet show for children from Christel's Puppenbühne , Zülpich

- Georg A. Weth : Little Red Riding Hood as a stage play for the family with 13 folk songs in a Schwalm setting (premier Japan 1991, DE 1992), published by VVB-Verlag Norderstedt

- Gerd-Josef Pohl: Little Red Riding Hood as a puppet show for children in kindergarten and elementary school age (Ed .: Piccolo Puppenspiele ), Bonn 2003

- Roland Richter: Little Red Riding Hood in the Hanau Marionette Theater in an alienated, parodic form

Opera

- François-Adrien Boieldieu : Le petit chaperon rouge . Paris 1818 (last German series of performances: Theater Lübeck 2001).

- Andreas Kröper : Little Red Riding Hood. A children's opera . Zurich 2008 (world premiere; libretto based on Mathilde Wesendonck , Zurich 1861; music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart , selection of various opera arias).

musical

- Peter Lund : Grimm - The really true story of Little Red Riding Hood and her wolf . World premiere Oper Graz 2014; Music by Thomas Zaufke

music

- Varg : Little Red Riding Hood on the Wolfskult album tells an alternative version of the story in which Little Red Riding Hood kills her grandmother and feeds her to the wolf. The song exists in two versions, once with Anna Murphy from Eluveitie and once with Robse from Equilibrium as a guest musician.

Film and television adaptations

The Little Red Riding Hood story was filmed for the first time in 1922, and was followed by numerous feature and cartoons that were closely based on the original. There are also a number of films that differ more or less strongly from the fairy tale or in which the Little Red Riding Hood figure is used in other contexts.

- 1922: Little Red Riding Hood , adapted from Walt Disney

- 1937: Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf (b / w, partly in color) - Director: Fritz Genschow

- 1943: Red Hot Riding Hood (modern, sexually connoted animation adaptation of the plot) - Directed by Tex Avery (MGM)

- 1949: Little Rural Riding Hood (animation adaptation) - Directed by Tex Avery (MGM)

- 1953: Little Red Riding Hood - Director: Fritz Genschow

- 1954: Little Red Riding Hood - Director: Walter Janssen

- 1960: Little Red Riding Hood - Director: Hans-Günter Bohm

- 1962: Little Red Riding Hood (in addition to the original by the Brothers Grimm, also excerpts from the original by the Russian writer Evgeni Lwowitsch Schwarz ) - Director: Götz Friedrich

- 1965: The Dangerous Christmas of Red Riding Hood , musical parody with Liza Minnelli in the title role; aired November 28, 1965 on ABC; the bad wolf presents the fairy tale from his point of view. - Directed by Sid Smith

- 1969: The Adventures of the Cappuccetto , Swiss TV puppet series

- 1977: About Little Red Riding Hood ( Russian Про Красную Шапочку ) , two-part Soviet film musical

- 1984: The Time of the Wolves - Director: Neil Jordan

- 1987: Grimms Märchen (Japanese cartoon series) - Season 1, episode 5: Little Red Riding Hood

- 1989: Little Red Riding Hood (Cannon Movie Tales: Red Riding Hood) - Director: Adam Brooks

- 1995: Little Red Riding Hood (Little Red Riding Hood) - Director: Toshiyuki Hiruma

- 1996: Freeway - Director: Matthew Bright

- 1999: Jin-Roh , ( anime political thriller in which, among other things, the cannibalistic version of the fairy tale is read out) - Director: Hiroyuki Okiura

- 1999: SimsalaGrimm (German cartoon series) - Season 2, Episode 2: Little Red Riding Hood

- 2005: Rotkäppchen - Germany, fairy tale film from the ZDF series Märchenperlen , director: Klaus Gietinger

- 2006: Little Red Riding Hood - Paths to Happiness , comedy from the ProSieben / ORF series Die Märchenstunde (Germany / Austria) - Director: Tommy Krappweis

- 2006: The Little Red Riding Hood Conspiracy - Director: Cory Edwards

- 2011: Red Riding Hood - Wolf Moon (Red Riding Hood) - Director: Catherine Hardwicke

- 2011: Once Upon a Time (US fantasy series) - Season 1, episode 15

- 2012: Rotkäppchen - Germany, fairy tale film of the 5th season from the ARD series Six in one fell swoop , directed by Sibylle Tafel

- 2013: Little Red Riding Hood: A Tale of Blood and Death (German short film) - Director: Florian von Bornstädt u. Martin Czaja

- from 2013: Ever After High , Shannon Hale

Radio plays

- Grammar / This wavering summer tone by Ute-Christine Krupp , Saarländischer Rundfunk , Saarbrücken 1995.

comics

Well-known comic interpretations of the material with a clearly erotic or pornographic orientation can be found among others. a. in a series by Zwerchfell Verlag from 2000, as well as by Mart Klein in a self-published diploma thesis from May 2009.

Computer games

The fairy tale was used in 2009 for the computer game " The Path ". The idea of the game is this: Since there is a risk of danger, the player should not leave the path to the grandmother's hut. But that is precisely what is possible and of course particularly seductive.

advertising

Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf were and are popular objects in advertising. Many products have already been advertised with these figures, including coffee, vinegar, beer, pastries, chocolate, sewing thread, knitting wool. The motif is particularly used in Rotkäppchen sparkling wine from Freyburg an der Unstrut, where the bottles are closed with a red cap. A department store advertised in 1990: “... Grandmother, why do you have so much money? ... “In a TV advertisement in 2018, Little Red Riding Hood knows that the car does not have to go to the authorized workshop in order to keep the guarantee (“ No more fairy tales ”).

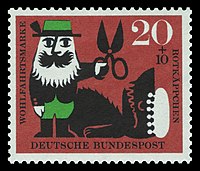

Philatelic

On February 11, 2016, the first day of issue, Deutsche Post AG issued three welfare stamps in the series Grimms Märchen with the titles Im Wald (value: 70 + 30 euro cents), At the grandmother (value: 85 + 40 euro cents) and Gutes Ende (value: 145 + 55 euro cents). The design of the brands comes from the graphic designers Lutz Menze and Astrid Grahl from Wuppertal.

Commemorative coins

On February 4, 2016, the Federal Republic of Germany issued a silver commemorative coin with a face value of 20 euros in the series “Grimms Märchen” . The motif was designed by Elena Gerber.

literature

- Jack David Zipes : Little Red Riding Hood's lust and suffering. Biography of a European fairy tale. Newly revised and expanded edition. Ullstein, Frankfurt 1985, ISBN 3-548-30170-3 .

- Marianne Rumpf: Little Red Riding Hood. A comparative fairy tale investigation . Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-8204-8462-0 . (Dissertation. University of Göttingen, 1951)

- Bruno Bettelheim: Children need fairy tales. dtv, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-423-35028-8 .

- Walter Scherf: The fairy tale dictionary. 2 volumes, Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-39911-8 .

- Kurt Derungs: The Psychological Myth: Women, Fairy Tales & Sexism. Manipulation and indoctrination through popular psychological fairy tale interpretation: Freud, Jung & Co. edition amalia, Bern 1996, ISBN 3-9520764-6-5 .

- Walter Sauer: 20 Rotkäppchen European-polyglot , Inkfaß Edition Neckarsteinach 2005, ISBN 3-937467-09-2

- Hans Ritz (Ed.): Pictures from Little Red Riding Hood. 2nd expanded edition. Kassel 2007, ISBN 978-3-922494-08-9 .

- Hans Ritz: The story of Little Red Riding Hood. Origins, analyzes, parodies of a fairy tale . 15th edition expanded to 296 pages. Muri-Verlag, Kassel 2013, ISBN 978-3-922494-10-2 .

- Verena Kast : The magic of Little Red Riding Hood , in: Forum, The magazine of the Augustinum in the 59th year , winter 2013, Augustinum Munich, issue 4, pp. 36–43.

Web links

- Little Red Riding Hood by Perrault Dt.

- Gutenberg-DE: Bechstein's Little Red Riding Hood

- Märchenlexikon.de on Little Red Riding Hood AaTh 333

- 1904 edition with illustrations by Arpad Schmidhammer

- Little Red Riding Hood illustrations, texts by Grimm, Ludwig Bechstein, Alexander von Ungern-Sternberg and Joachim Ringelnatz

- Little Red Riding Hood as an mp3 audio book on LibriVox

- Little Red Riding Hood as a ballet piece - as part of Tchaikovsky's Sleeping Beauty (3rd act, ball of fairy tale characters), web video from the Russian National Ballet

- Astrid van Nahl : Little Red Riding Hood Variations (in the picture book) at alliteratus.com , PDF file 128 KB

- Illustrations, versions of text and interpretations of Little Red Riding Hood on SurLaLuneFairyTales.com

Individual evidence

- ^ Charles Perrault: Little Red Riding Hood.

- ↑ Bruno Bettelheim: Children need fairy tales. 31st edition. dtv, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-423-35028-0 , pp. 191-211.

- ↑ Frederik Hetmann: dream face and magic trace. Fairy tale research, fairy tale studies, fairy tale discussion. With contributions by Marie-Louise von Franz, Sigrid Früh and Wolfdietrich Siegmund. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-596-22850-6 , pp. 128-129.

- ^ Bernhard Schmid: Belladonna. In the deep forest. In: Documenta Homoeopathica. Volume 17. Verlag Wilhelm Maudrich, Vienna / Munich / Bern 1997, pp. 141–150; Herbert Pfeiffer: The environment of the small child and its medicine. In: Uwe Reuter, Ralf Oettmeier (Hrsg.): The interaction of homeopathy and the environment. 146th Annual Meeting of the German Central Association of Homeopathic Doctors. Erfurt 1995, pp. 46-64; Martin Bomhardt: Symbolic Materia Medica. 3. Edition. Verlag Homeopathie + Symbol, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-9804662-3-X , pp. 518, 1376.

- ↑ Manfred Spitzer: Little Red Riding Hood and the Stress. (Relaxing) exciting things from brain research. Schattauer, Stuttgart 2014. ISBN 978-3-86739-102-3 , pp. 23-26.

- ↑ The children's and house tales of the Brothers Grimm . Published by Friedrich Panzer, Wiesbaden 1947, p. 299.

- ↑ Children's and Household Tales , Volume 1, Berlin 1819, p. 77

- ↑ Lykke Aresin , Helga Hörz , Hannes Hüttner , Hans Szewczyk (eds.): Lexikon der Humansexuologie. Verlag Volk und Gesundheit, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-333-00410-0 , p. 208.

- ↑ On the question of who wrote the anti-Nazi Rotkäppchensatire of 1937, see the discussion of the various theories of authorship in: Hans Ritz, Die Geschichte vom Rotkäppchen, origins, analyzes, parodies of a fairy tale, 15th edition, expanded to 296 pages, Kassel 2013 (p . 274–281)

- ↑ Squidward Troll: Little Red Riding Hood. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Ed.): Grim fairy tales. Prose texts from Ilse Aichinger to Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X , pp. 132-133. (Around 1953; first published in: Lutz Röhrich (Ed.): Gestures, Metaphor, Parodie. Studies on Language and Folk Poetry. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1967, pp. 139–141.)

- ↑ Squidward Troll: Little Red Riding Hood. In: Johannes Barth (ed.): Texts and materials for teaching. Grimm's fairy tales - modern. Prose, poems, caricatures. Reclam, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-15-015065-8 , pp. 73-75. (1963; first published in: Thaddäus Troll: Das große Thaddäus Troll-Lesebuch. With an afterword by Walter Jens. Hoffmann & Campe, Hamburg 1981, pp. 149–152.)

- ↑ Anneliese Meinert: Little Red Riding Hood. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Ed.): Grim fairy tales. Prose texts from Ilse Aichinger to Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X , pp. 134-135. (First published in 1965 as: Rotkäppchen '65. In: Lutz Röhrich (Ed.): Gestures, metaphors, parodies. Studies on language and folk poetry. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1967, pp. 149–150.)

- ↑ Rudolf Otto Wiemer: The old wolf. In: Johannes Barth (ed.): Texts and materials for teaching. Grimm's fairy tales - modern. Prose, poems, caricatures. Reclam, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-15-015065-8 , p. 76. (1976; first published in: Hans-Joachim Gelberg (Ed.): Neues vom Rumpelstilzchen and other house fairy tales by 43 authors . Beltz & Gelberg, Weinheim / Basel 1976, p. 73.)

- ↑ Max von der Grün: Little Red Riding Hood. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Ed.): Grim fairy tales. Prose texts from Ilse Aichinger to Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X , pp. 136-139. (First published in: Jochen Jung (Hrsg.): Bilderbogengeschichten. Fairy tales, sagas, adventures. Newly told by authors of our time. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1976, pp. 95–97.)

- ↑ Peter Rühmkorf: Little Red Riding Hood and the wolf's fur. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Ed.): Grim fairy tales. Prose texts from Ilse Aichinger to Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X , pp. 140-147. (1981; first published in: Hans Ritz, Die Geschichte vom Rotkäppchen, origins, analyzes, parodies of a fairy tale , 1st edition, Muriverlag, Emstal 1981, and Peter Rühmkorf: Der Hüter des Misthaufens. Enlightened fairy tales. Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek 1983, Pp. 229–238.)

- ↑ Janosch: The electric Little Red Riding Hood. In: Janosch tells Grimm's fairy tale. Fifty selected fairy tales, retold for today's children. With drawings by Janosch. 8th edition. Beltz and Gelberg, Weinheim / Basel 1983, ISBN 3-407-80213-7 , pp. 102-107.

- ↑ Slawomir Mrozek: Little Red Riding Hood. In: Johannes Barth (ed.): Texts and materials for teaching. Grimm's fairy tales - modern. Prose, poems, caricatures. Reclam, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-15-015065-8 , pp. 76-77. (1985; first published in: Slawomir Mrozek: Life is difficult. Satiren. German by Klaus Staemmler. Dtv, Munich 1985, pp. 67–68.)

- ↑ Michael Freidank: Rotkäppschem. In: Johannes Barth (ed.): Texts and materials for teaching. Grimm's fairy tales - modern. Prose, poems, caricatures. Reclam, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-15-015065-8 , p. 78. (2001; first published in: Michael Freidank: Whom is the hottest chick in Land? Fairy tales in Kanakisch un so. Eichborn, Frankfurt a. M . 2001, pp. 71-72.)

- ↑ The Horen . Vol. 1/52, No. 225, 2007, ISSN 0018-4942 , pp. 21-25, 35-36, 219.

- ↑ Karen Duve: Grrrimm. Goldmann, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-442-47967-2 , pp. 99–153.

- ↑ ed. by Walter Sauer, see literature

- ↑ Behrens, Volker: Durchgeknallte Märchenerzähler, In: Hamburger Abendblatt, March 29, 2016, p. 1

- ↑ List of Rotkäppchen films in the Internet Movie Database (IMDb) ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ compare invasion of the fairy tale kingdom , under einestages.spiegel.de .

- ↑ Grammar / This wavering summer tone in the HörDat audio play database .

- ↑ Review of Grimm - No. 2: Little Red Riding Hood

- ↑ Review of Little Red Riding Hood from Unfug-Verlag