Prokop Diviš

Prokop Diviš (original form of the name: Václav Divíšek , Latinized Procopius Divisch , German Prokop Diwisch in which physikalgeschichtlichen literature Prokop Devic ) (* 26. March 1698 in Helvíkovice ; † 25. December 1765 in Přímětice ), was a Czech Prämonstratenser - Canons as well as a frontier scientific scholar and inventor.

Life

Prokop Diviš, who was born in East Bohemia and then worked in South Moravia, attended the Jesuit Latin school in Znojmo and studied philosophy in the Premonstratensian Monastery of Klosterbruck since 1720 . He joined the order in November 1720 and was ordained a deacon in 1725 . In 1726 he was ordained a priest. Then he studied theology. He graduated from the University of Salzburg in 1734 . Back in Louka, he was prior there until 1742 and one year before that he took over the monastery parish in Přímětice, where he worked as a pastor until his death.

The priest, who was interested in science, initially dealt with hydrotechnology. From the late 1740s, Diviš then carried out experiments with electricity. He examined the influence of electricity on plants and tried to heal with electricity. These studies initially gave him recognition in specialist circles; He corresponded with the Prague physics professor Jan Antonín Scrinci and kept up to date with the European state of research in his remote parish. Before 1750 he was invited to the Viennese court as a guest and is said to have carried out experiments before Franz I , and in 1750 also to have worked with Joseph Franz .

When a lightning bolt killed Professor Georg Wilhelm Richmann on July 26, 1753 during his thunderstorm electrical experiments in Saint Petersburg, Prokop Diviš sent the Academy of Sciences to Petersburg a short Latin treatise on his own theories on atmospheric electricity, taking into account the tragic incident. Diviš also came into contact with the mathematician Leonhard Euler and the Vienna Academy of Sciences, he was of the opinion that one could protect the Vienna Hofburg from thunderstorms with a device he designed.

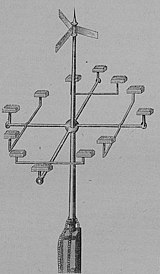

The interest of those so addressed was limited, as Diviš had meanwhile developed his own theories, which he underpinned with natural philosophy. The scientists saw it as an attempt (not uncommon at this time) to combine theology and physics, which increased their skepticism. Convinced of his views despite the lack of further correspondence, Diviš set up a "meteorological machine" in his parish garden on June 15, 1754: an arrangement with 400 wire tips, with which he hoped to suck off the air electricity so that thunderstorms as large as possible could be prevented entirely. The “machine” stood free on a 40 meter high post and was attached with iron chains, which were supposed to serve primarily for stabilization, but also practically had a grounding effect. The inauguration of the device was accompanied by national media coverage.

The farmers, who Diviš had financially involved in his private project, grew increasingly disgruntled by the priest's declared intention to influence the weather. When a drought hit the village in the summer of 1759, they destroyed the device in the church garden at night, which the pastor always claimed to keep storms away. After letters of protest from the population to his superiors, Diviš was asked by the church leadership to cancel the project and to hand over his second weather machine (now inaccessible on the church tower) to Klosterbruck Abbey.

Diviš continued to correspond with the Protestant theologians Johann Ludwig Fricker and Friedrich Christoph Oetinger from Württemberg and achieved a publication of his work on Magia naturalis . However, it only appeared posthumously under the title of the editor Friedrich Christoph Oetinger The theory of meteorological electricity that has long been demanded . The long-awaited and ambitiously sought appointment by Diviš as a member of an Academy of Sciences never took place.

reception

While Euler, Tetens and also scientists at the Viennese court disliked Diviš's theory, from the middle of the 19th century he was again perceived as a thought leader and inventor who is said to have invented the lightning rod independently of Benjamin Franklin . In this reporting, his achievements and the judgment of his contemporaries were glossed over.

Although Diviš's test arrangement did not provide for the protection of tall buildings and was ineffective in its position in the open to protect an entire village, it was later unreflectedly perceived as an early lightning rod, so that its inventor Diviš was stylized as the "European Franklin". Heinrich Meidinger already tried in 1888 to refute this myth, which had arisen from local patriotism. Due to the continuing interest, two Czech science historians compiled material on the case at the beginning of the 21st century.

Inventions

- Denis d'or ("Goldener Dionysius", "Goldener Diwisch"), a now unidentifiable, allegedly electronic musical instrument , manufactured only as a prototype , which could give a player an electric shock for fun.

- Thunderstorm machine (lightning rod), Diviš built it in 1754 next to his rectory in Přímětice.

Works

In 1755 Diviš took part with his treatise Deductio theoretica de electrico igne in a competition on electricity, in which the astronomer Johann Albrecht Euler , a son of Leonhard Euler, received the prize. Since Diviš's work Magia naturalis on electricity was rejected by the censorship in Vienna , he let the Herrenberg special superintendent Friedrich Christoph Oetinger under the title Procopii Divisch Theologiae Doctoris & Pastoris zu Prendiz bey Znaim in Moravia in the long-requested theory of the meteorological electricity in 1765 Publish Tübingen .

Scientific treatises

- Alpha, et omega. Seu principium, et finis duobus tractatibus […] constans 1735.

- Deductio theoretica de electrico igne. 1755.

- The theory of meteorological electricity has long been demanded. 1765.

- Ara Theologica. 1735.

- Descriptio machinae meteorologicae.

- Reflexio Procopii Divisch sanctae scripturae doctoris canonici Praemonstratensis super infeliciter tentatum experimentum meteorologicum a domino professore Richmanno Peterburgensi the 26th julii 1753.

literature

- Reinhard Breymayer : Bibliography on Prokop Diviš. In: Friedrich Christoph Oetinger : The school chart of the Princess Antonia. Edited by Reinhard Breymayer and Friedrich Häußermann. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1977, T. 2, pp. 431-453.

- The works of Friedrich Christoph Oetinger. Chronological-systematic bibliography 1707–2014. edited by Martin Weyer-Menkhoff and Reinhard Breymayer. (= Bibliography on the history of Pietism. Volume 3). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin a. a. 2015, ISBN 978-3-11-041450-9 , pp. 184, 191–194, 216, 297, 373 on Prokop Diviš.

- Wolfgang Grassl: Culture of Place: An Intellectual Profile of the Premonstratensian Order. Bautz, Nordhausen 2012, pp. 347–352.

- Luboš Nový (ed.): Dějiny exactních věd v českých zemích do konce 19. století. Prague 1961.

- Constantin von Wurzbach : Diwisch, Procop . In: Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich . 3rd part. Typogr.-literar.-artist publishing house. Establishment (L. C. Zamarski, C. Dittmarsch & Comp.), Vienna 1858, pp. 324–326 ( digitized version ).

- Divisch, Procopius . In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 4th edition. Volume 5, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885–1892, p. 10.

- Karl Bornemann: Procop Diwisch. A contribution to the history of the lightning rod . In: The Gazebo . Issue 38, 1878, pp. 624–627 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

Web links

- Literature and other media by and about Prokop Diviš in the catalog of the National Library of the Czech Republic

Remarks

- ↑ a b c d e Christa Möhring: A story of the lightning rod. The derivation of lightning and the reorganization of knowledge around 1800. (PDF) Dissertation, pp. 83-105.

- ^ A b Constantin von Wurzbach : Diwisch, Procop . In: Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich . 3rd part. Typogr.-literar.-artist publishing house. Establishment (L. C. Zamarski, C. Dittmarsch & Comp.), Vienna 1858, pp. 324–326 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Karl Bornemann: Procop Diwisch. A contribution to the history of the lightning rod . In: The Gazebo . Issue 38, 1878, pp. 624–627 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- ^ Karl Vocelka : Splendor and Fall of the Courtly World. Representation, reform and reaction in the Habsburg multi-ethnic state. In: Herwig Wolfram (Ed.): History of Austria 1699–1815. Vienna 2001, p. 269 f.

- ↑ Joseph Smolka, Joseph Haubelt: Oetinger friend Procopius Diwisch (1698-1765). In: Gerhard Betsch, Eberhard Zwink, Sabine Holtz (eds.): Mathesis, natural philosophy and arcane science in the vicinity of Friedrich Christoph Oetinger. Conference report of the international conference at the University of Tübingen, 9. – 11. October 2002 (= Contubernium. Tübingen Contributions to University and Scientific History. 63). Tübingen 2004/2005.

- ↑ Peer Sitter: The Denis d'or: Ancestor of the "electroacoustic" musical instruments? ( Memento of the original from January 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Diviš, Procopius |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Divis, Prokop; Divíšek, Václav; Divisch, Procopius; Divisch, Procop; Divisch, Prokop; Diwisch, Prokop; Devic, Procopius |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Czech priest, scholar and inventor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 26, 1698 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Helvíkovice nad Orlicé, Helkowitz on the Wild Eagle in Bohemia |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 25, 1765 |

| Place of death | Přímětice , Brenditz in Moravia |