Qi (state)

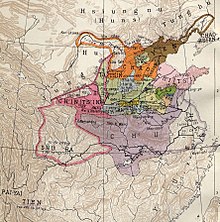

Qi ( Chinese 齊國 / 齐国 , Pinyin Qí Guó , W.-G. Ch'i ) was a relatively powerful state in ancient China . It was in the north of what is now Shandong . The capital of the state, Linzi , was near today's Zibo .

Qi arose in the 11th century BC as a feudal state of the House of Zhou and went into effect in 221 BC. When it was conquered by Qin . It thus existed in the Western Zhou Dynasty (1046 to 771 BC), in the spring and autumn annals (722 to 481 BC) and in the Warring States Period (475 to 221 BC) .).

The rule of the Jiang family ( 姜 ) over qi lasted for several centuries until it was ruled in 384 BC. Was forcibly ended by the Tian family ( 田 ). The state was able to dominate China of the Zhou dynasty several times and mostly lost its dominance through internal power struggles.

founding

Qi emerged as a feudal state as part of the colonization of eastern China by the Zhou dynasty after the civil war of succession between the descendants of King Wu was over. King Cheng sent members of the royal family to eastern China in order to establish feudal states in strategically important locations and thus secure the Zhou territory, which had expanded significantly in the course of the civil war. Tai Gong Wang , who had commanded the Zhou army when the Shang dynasty was overthrown , received Qi, Qi's northern neighbor Yan was given to Shao Gong Shi , the western neighbor Lu with its center near today's Jinan went to King Cheng's cousin, Bo Qin .

The Qi located on the Shandong Peninsula was supposed to secure the trade and traffic routes between north and south China, at the same time it benefited economically from its location on these trade routes. The salt production on the seashore was very profitable. Fishing and the manufacture of textiles flourished. It ruled the non-Chinese tribes that settled along the coast; by the tribes outside the northern border Qi was attacked repeatedly, especially by Di . As a state on the periphery, Qi still had the opportunity to expand through the incorporation of non-Chinese tribes and their territory.

Together with his neighbor Lu , Qi was one of the most important pillars of the Zhou dynasty . Qi played an active role in numerous Zhou military operations.

Time of spring and autumn annals

At the beginning of the spring and autumn annal period, qi was among the strongest fifteen states, while the Zuo zhuan Chronicle mentions 148 states, most of which were very small.

When the authority of the Zhou kings began to wane and Zheng usurped supremacy, qi recognized this, but was too powerful to be attacked by Zheng. After Zheng's supremacy declined, Qi gradually assumed this role. The ruler Qi Huan Gong and his advisor Guan Zhong made Qi the first among the Zhou feudal states to reform the feudal system. The relatively loose social structure of feudal administration, in which the nobility was organized in the form of a pyramid, administered and leaned on their fiefs, was replaced by a centralized system. Qi was divided into 15 administrative units, with the ruler of Qi and each of the two highest-ranking ministers each commanding five of these units. The traders and craftsmen were divided into six administrative units, the guo ren and ye ren into four administrative levels each. The civil and military functions of these levels were combined and a command structure with the ruler at the head was introduced. The holders of the posts within this command structure were punished or rewarded according to their performance. Qi thus created an administrative structure that enabled a much faster mobilization of people and material than in the other states at the same time.

Until 667 BC One state after the other swerved to the line of qi. Partly they were militarily coerced by Qi, partly they owed Qi. Qi also annexed 35 small neighboring states during this phase. In 667, the rulers of Lu , Song , Chen and Zheng chose the state of Qi or its ruler Qi Huan Gong as their leader. As a result, King Hui of Zhou sent a high-ranking minister to Huan Gong to make him hegemon (Ba). Associated with this new title was the privilege of conducting military actions on behalf of Zhou to restore and maintain the authority of the Son of Heaven .

With this order, Huan Gong moved in 671 BC. BC against Wey because his ruler had previously supported a rebellion by King Hui's brother. He then intervened in a power struggle in Lu State. In 664 BC Qi came to the aid of his neighbor Yan to protect him from attacks by non-Chinese rong ; the latter had bundled their forces in what is now north and east Hebei . In 662, non-Chinese Chi Di invaded Xing State (now Central Hebei). Xing was born in 659 BC. Chr. Destroyed. At the urging of Guan Zhong, Huan Gong marched against the Di with troops from Qi, Song and Cao , and the population of Xing was assigned another location for the construction of a new capital. A Qi garrison town was established in Xing. In 660 BC The Chi Di attacked Wey and killed the Wey ruler. Once again Qi came to the rescue, a new Wey capital was founded and a son of the deceased ruler was installed as the new head. Qi military was also stationed in Wey. Thanks to these interventions, Huan Gong had become the undisputed leader of the Zhou states.

At the same time as these events, the Chu state in the Yangtze Valley , whose inhabitants at the time belonged to non-Chinese peoples who had united to form states, grew stronger . As early as 706 BC Chr. Chu expanded north and attacked the state of Sui . One of the rulers of the Chu began to use the title of king, which until then was only reserved for the Zhou heads. In 656 BC BC Huan Gong forged an alliance of eight states and attacked Chu's satellite state Cai . After the fall of Cai, the Chu ruler felt compelled to attend a meeting of all the rulers who Huan Gong had called to Shaoling . Such meetings took place several times in the following, they served Qi as a means to make his determination to maintain the existing order credible. The delegates had to swear to preserve the feudal structure of the Zhou dynasty. Huan Gong tried to use his influence as a hegemon to create an order based on multilateral consensus instead of authority.

The status of Qi as a hegemon waned after Guan Zhong and shortly afterwards Huan Gong (645 and 643 BC) died and five sons fought over the succession to the throne. Because of the succession struggles, even Huan Gong's funeral was delayed. The sons of Huan Gong could not regain the status of the hegemon. It passed to Jin for the next three generations ; nevertheless, Qi remained one of the dominant powers in China in the 7th century BC alongside Jin, Qin and Chu. Chr.

In 632 BC In addition to Qin and Song , Qi participated in an army of Jin to take action against Chu. Chu was severely beaten at Chengpu . After the death of Jin Wen Gong around 628 BC. In BC Qi and Qin began to question the Jin supremacy. In 589 BC Qi invaded Lu and Wey , but is forced to withdraw by Jin. Under Jin Li Gong the northern states again allied against Chu in 579 BC. A minister from Song arranged a meeting between the four states. Qi subsequently joined the first known intergovernmental disarmament agreement, which only lasted a few years.

Warring States Period

During the first 150 years of the Warring States' era, qi spread to the south of the Shandong Peninsula .

From the middle of the 4th century BC Qi was the main giver of alimony and titles to scholars so that they could go about their business. Qi was the first Chinese state to see it as a state's task to raise its reputation by supporting scholarship.

In the 6th century BC The Tian clan, who held many ministerial offices in Qi, became more and more powerful and began to dominate Qi. Until 532 BC The Tian succeeded in eliminating rival clans. In 485 BC The head of the Tian clan murdered the heir to the throne of the ruler who had died shortly before. In his place he put a child on the throne. In the civil war that followed, another child was enthroned and again murdered. The method by which the Tian clan came to power in qi was imitated in other states and is typical of the beginning of the Warring States Period.

Around 300 BC BC the influence of Qi increased again temporarily. Qi tried to annex the small state of Song because it was interested in the city of Dingtao , which was then considered the richest trading city. In 288 BC Qin and Qi entered into an alliance, subsequently both rulers temporarily - and for the first time in the history of China - assumed the title of Emperor (Di). Both states agreed to attack Zhao . However, the adviser Su Qin from Yan convinced the King of Qi that Qi should work towards conquering Song and weakening Qin. Qi's success in taking Song led to an alliance of all other states against Qi, which Tian Wen, who fled Qi to Wei , had arranged. In 284 BC BC Yan invaded Qi; Yan had traditionally been a firm ally of qi, so that the border between yan and qi was not very secure. The attack led by Yue Yi was surprising and devastating for Qi because it was attacked simultaneously by Zhao, Hann and Wei. King Qis was killed, almost the entire territory occupied. A relative of the king named Tian Dan succeeded in 279 BC. To regain control of the qi territory, but from then on qi could no longer compete with qin.

In 221 BC Qi was conquered by Qin as the last of the earlier Zhou feudal states. As a result, the entire area settled by Chinese was united under a single ruler, who was to proclaim himself Qin Shihuangdi as the first emperor and establish the Qin dynasty .

archeology

Qi's capital Linzi , located near today's Zibo , is one of the most famous cities in Chinese history . Excavations have been going on in the area of this city since the 1930s. Linzi is an example of cities with double city walls, which were found several times in cities from the Warring States period. The outer city wall encloses a territory of 5200 meters north-south and 3300 meters east-west. The inner city wall is located in the southwest part of the city area and was only built during the Warring States Period, probably as an extension of the Tian clan's estate. The inner city wall is between 28 and 38 meters thick and surrounded by moats. This reflects the great concern for safety, with dangers more likely to come from the city than from the surrounding area. In addition to the palace of the rulers, Linzi also housed workshops for iron and bronze processing and the Jixia Academy , where thinkers such as Zou Yan , Xun Kuang , Chunyu Kun or Shen Dao were employed.

Numerous ritual bronzes came to light during the excavations . About 30 graves of nobles from the Zhou period have been discovered, including probably the tomb of Qi Jin Gong , which has a large stone burial chamber and pits for ritual sacrifices, including 600 horses.

Individual evidence

- ^ Edward L. Shaughnessy: Western Zhou History . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 312 .

- ↑ a b c Cho-yun Hsu : The Spring and Autumn Period . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 554 .

- ^ Edward L. Shaughnessy: Western Zhou History . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 313 .

- ↑ Cho-yun Hsu : The Spring and Autumn Period . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 550 .

- ↑ a b Cho-yun Hsu : The Spring and Autumn Period . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 553 .

- ↑ Cho-yun Hsu : The Spring and Autumn Period . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 547 .

- ↑ a b c d e Cho-yun Hsu : The Spring and Autumn Period . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 555 .

- ↑ a b Cho-yun Hsu : The Spring and Autumn Period . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 568 .

- ↑ a b c Cho-yun Hsu : The Spring and Autumn Period . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 556 .

- ↑ a b Cho-yun Hsu : The Spring and Autumn Period . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 557 .

- ↑ Cho-yun Hsu : The Spring and Autumn Period . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 558 .

- ↑ Cho-yun Hsu : The Spring and Autumn Period . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 559 .

- ↑ Cho-yun Hsu : The Spring and Autumn Period . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 560 .

- ↑ Cho-yun Hsu : The Spring and Autumn Period . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 561 .

- ^ Mark Edward Lewis : Warring States Political History . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 643 .

- ^ Mark Edward Lewis : Warring States Political History . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 598 f .

- ^ Mark Edward Lewis : Warring States Political History . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 637 f .

- ↑ Derk Bodde : The state and empire of Ch'in . In: Denis Twitchett and John K. Fairbank (Eds.): The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC-AD220. Cambridge University Press, 1986, ISBN 0-521-24327-0 , pp. 45 .

- ^ Mark Edward Lewis : The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han . Belknap Press, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-674-02477-9 , pp. 35-37 .

- ^ A b Mark Edward Lewis : Warring States Political History . In: Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Ancient China . Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8 , pp. 664 f .