Red fear

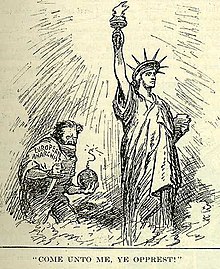

The term Rote Angst ( English Red Scare ) summarizes two different periods in US history that were characterized by anti-communist hysteria, which manifested itself in the stigmatization and persecution of the political left , especially of immigrants .

First Red Fear (1917–1920)

The seizure of power by the Communist Bolsheviks in Russia in the course of the October Revolution of 1917 sparked great social unrest in the United States and fueled fears among conservative politicians and part of the population that a communist upheaval in the United States would endanger the basic capitalist order and the liberal lifestyle or even destroy it. Together with the other Western powers , US troops intervened in the Russian Civil War on the side of the whites in northern Russia and the Far East from 1918 .

These fears were fueled both by the rise of left-wing parties and the founding of the Communist Party and the Communist Workers' Party in 1919, as well as by numerous spectacular strikes carried out by the radical left-wing union, the Industrial Workers of the World . In addition, the US government was angry that many left-wing politicians, such as E.g. the leader of the Socialist Party (SPA) Eugene V. Debs , rejected the participation of the USA in the First World War and also expressed criticism after the entry into the war.

In view of this situation and still under the influence of the First World War, the government passed a series of laws that made it a criminal offense to hinder the use of the US army in war ( Espionage Act of 1917) or to publicly criticize the government and the military ( Sedition Act of 1918 ). In addition, anarchist-minded foreigners were prohibited from entering the country and deportation of already (illegally) immigrated anarchists was allowed ( Anarchist Exclusion Act of 1918 ), which was later made even more stringent by the Immigration Act of 1924 , which stipulated a highly restrictive immigration policy.

With the founding of the Committee on Public Information ( Creel Commission ) in 1917, the then President Woodrow Wilson also created an institution which, through massive propaganda work , sought to spread a distorted image of Americans of German descent to the public and supported the formation of patriotic organizations that were spied on of the population should track down “spies and traitors”.

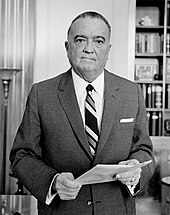

The main public excitement was the efforts of militant immigrants around the Italian anarchist Luigi Galleani to overthrow the US government with a violent overthrow. After these anarchist groups carried out a series of bomb attacks in eight American cities on June 2, 1919, including the house of Attorney General Alexander Mitchell Palmer , the latter, together with his assistant J. Edgar Hoover, began a large-scale wave of persecution and arrests against political parties Organize radicals , anarchists, socialists and communists. As a result of this action, later known as the Palmer Raids , more than 10,000 people were arrested - the largest mass arrest in US history to date - and the foreigners underneath them were deported to Europe by ship, including the well-known anarchist and peace activist Emma Goldman .

These massive reprisals , which were initially also supported by the general public, led the Communist Party to go underground and caused the political influence and membership of the trade unions and the Socialist Party to decline rapidly. At the beginning of 1919 the SPA still had more than 100,000 members, in 1921 it was only around 13,000, which corresponds to a decrease of almost 90% within just two years.

This “First Red Fear” finally came to an end when Palmer warned of a communist revolution in the USA, which he predicted to break out on May 1, 1920. When this failed to materialize, however, he lost his credibility and also his political influence. It also became public that many of the deportations and arrests he had ordered lacked any legal evidence.

Second Red Fear (1947–1957)

In the face of the looming Cold War between the Western powers and the Eastern bloc at the end of the Second World War , another wave of anti-communist mass hysteria broke out over the USA . Fearing communist infiltration and Soviet agents, the US government launched a campaign against the Communist Party (CPUSA) , its members and (alleged) sympathizers in order to find “ subversive elements”.

These actions were coordinated and directed on the one hand by the Committee for Un-American Activities , a committee of the House of Representatives that hunted down Communist sympathizers in the civil service and dedicated itself to combating communist propaganda in the film industry ( Hollywood Ten ). On the other hand, the Senate set up a similar committee in 1952 ( Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations ), which, under the leadership of Senator Joseph McCarthy , began to examine officials of the state and government apparatus in public hearings for communist sentiments.

Similar efforts have also been made by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) under J. Edgar Hoover , which investigated denouncing , anonymous reports about communist-minded federal employees, discredited and monitored left-wing organizations and parties ( COINTELPRO ) and classified files on public figures and high-ranking politicians created.

The image of this “Second Red Fear” was significantly shaped by McCarthy's media presence in the course of his investigations and his (often unfounded) communist conspiracy theories , which were viewed quite critically by the public. As a reaction to this so-called McCarthy era , a counter-movement emerged, which these serious encroachments on the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Bill of Rights , such as B. the right to freedom of expression ( 1st additional article ) or the right to refuse to provide information ( 5th additional article ), was heavily criticized. So remarked Albert Einstein , the next Bertolt Brecht , Thomas Mann was summoned and hundreds of others that it is a

“'Art of the Inquisition' acts that 'violates the spirit of the constitution' by placing 'under suspicion' in the name of external danger 'all intellectual efforts in public [...]' and 'all those who are not ready to submit To remove them from their positions, that is, to starve them out. ' "

As a result, many of the investigations and resulting punishments subsequently by the Supreme Court for unconstitutional explained and, if possible, revised.

The most famous victims of this hysteria were Ethel and Julius Rosenberg , who were charged with espionage on June 19, 1953, despite violent national and international protests and the like. a. of Pope Pius XII. , Jean-Paul Sartre , Albert Einstein , Pablo Picasso , Fritz Lang , Bertolt Brecht and Frida Kahlo , executed were. (After a new trial in 1993 to acquit the couple - published in 2008 by the New York Times - Richard Nixon , then Vice President under Dwight D. Eisenhower , also admitted that “significant errors were made” and “incriminating material manipulated” .)

McCarthy himself also fell into the crossfire of criticism after his rigid interrogation methods were made public on television in 1954. A committee of inquiry that was set up found him guilty, whereupon the Senate expressed its distrust and McCarthy had to resign as committee chairman.

The (media-fueled) communism paranoia had an impact in particular on Latin America , which is influenced by the US ; The CIA went the furthest with Operation PBSUCCESS , in which the democratically elected President of Guatemala was overthrown in 1954 , after which the country suffered 40 years of military terror and civil war and the achievements of the new constitution of 1944 were undone. In 2011, the Guatemalan government apologized to the family of President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán , who was elected with a 2/3 majority , and the family has been trying to get an apology from the USA ever since.

See also

literature

- Albert Fried: McCarthyism, The Great American Red Scare: A Documentary History . Oxford University Press , New York 1997, ISBN 0-19-509701-7 .

- Brian Fitzgerald: McCarthyism. The Red Scare (Snapshots in History) . Compass Point Books, 2007, ISBN 978-0-7565-2007-6 .

- John Earl Haynes: Red Scare or Red Menace? American Communism and Anticommunism in the Cold War Era . Ivan R. Dee, Chicago 1996, ISBN 1-56663-090-8 .

- Joy Hakim: War, Peace, and All That Jazz . Oxford University Press, New York 1995, ISBN 0-19-509514-6 .

- Kenneth D. Ackerman : Young J. Edgar: Hoover, the Red Scare, and the Assault on Civil Liberties . Da Capo Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-7867-1775-0 .

- Murray B. Levin: Political Hysteria in America: The Democratic Capacity for Repression . Basic Books, New York 1971, ISBN 0-465-05898-1 .

- Paul Avrich : Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America . Princeton University Press, Princeton 1996, ISBN 0-691-04494-5 .

- Robert K. Murray: Red Scare: A Study in National Hysteria, 1919-20 . McGraw-Hill, New York 1964, ISBN 0-8166-5833-1 .

- Tad Morgan: Reds: McCarthyism in Twentieth-Century America . Random House, New York 2003, ISBN 0-679-44399-1 .

- Stephen Schlesinger: Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala (= David Rockefeller Center Series on Latin American Studies . No. 4 ). Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. 2005, ISBN 0-674-01930-X (first edition: 1982).

Individual evidence

- ^ Murray B. Levin: Political Hysteria in America: The Democratic Capacity for Repression . Basic Books, New York 1971, ISBN 0-465-05898-1 , pp. 29 ff .

- ^ A b Socialism in America. In: Travel and History. Online Highways, 2007, accessed August 2, 2009 .

- ↑ a b Nick Abbe: On the way to tyranny? In: Telepolis . Heise Zeitschriften Verlag, November 5, 2007, p. 2 , accessed on August 2, 2009 .

- ^ Paul Avrich : Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America . Princeton University Press , Princeton 1996, ISBN 0-691-04494-5 .

- ^ Socialist Party of America - Annual Membership Figures. marxisthistory.org, accessed July 22, 2013 .

- ↑ Joy Hakim: War, Peace, and All That Jazz . Oxford University Press, New York 1995, ISBN 0-19-509514-6 , pp. 34-36 .

- ^ Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations: Intelligence Activities and the Rights of Americans - Book 2 - Final Report. April 26, 1976, archived from the original on June 15, 2002 ; accessed on May 5, 2014 .

- ↑ Nick Abbe: On the way to tyranny? In: Telepolis . Heise Zeitschriften Verlag, November 5, 2007, p. 3 , accessed on May 5, 2014 .

- ^ Johanna Lutteroth: US nuclear espionage drama. Together in death in one day on Spiegel Online from June 18, 2013.

- ↑ See Michael Kunczik: Public Relations for States. Cultivating the image of nations as an aspect of international communication. In: mass communication. Theories, methods, findings (Ed. Max Kaase, Winfried Schulz). Opladen 1989, p. 177 f: "According to McCann, much of the coverage of Central America in the North American press between 1953 and 1960 consisted of news from United Fruit's PR department ."

- ↑ nytimes.com The family of the fallen Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, who died in unexplained circumstances, awaits an apology from the US for Guatemala and 200,000 dead in the civil war after the CIA-initiated coup.