Wood pigeon

| Wood pigeon | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Wood pigeon ( Columba palumbus ) |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||

| Columba palumbus | ||||||||||

| Linnaeus , 1758 |

The wood pigeon ( Columba palumbus ) is a bird art from the family of pigeons ( Columbidae ). It is the largest species of pigeon in Central Europe and inhabits large parts of the Palearctic from North Africa, Portugal and Ireland east to Western Siberia and Kashmir . Noticeable features are the white wing bands and the white neck stripe. Wood pigeons, also called forest pigeons in German-speaking countries , inhabit wooded landscapes of all kinds, but also avenues, parks and cemeteries, today even in the centers of cities. As with most species in the family, the diet is almost exclusively plant-based. Depending on its geographical distribution , the wood pigeon is a stationary bird , part migrant or predominantly short-distance migrant and spends the winter mainly in western and south-western Europe. Despite the heavy hunt, the species is a frequent breeding bird in many countries and is not endangered in Europe.

description

Wood pigeons are large, powerfully built pigeons with a relatively long tail and a rather small head. With a body length of 38–43 cm and a wingspan of 68–77 cm, they are the largest pigeons in Central Europe. The sexual dimorphism is weak in terms of size and weight, males are slightly larger and heavier than females. Freshly dead males from East Germany had a wing length of 240–267 mm, with an average of 254 mm; Females reached 238–260 mm, with an average of 249 mm. The weight is subject to seasonal fluctuations and is highest in autumn and early winter due to the depot fat. For example, adult males collected in southern Sweden from August to September weighed 465–613 g, a mean of 539 g; Females weighed 420–600 g, mean 498 g; males collected there from December to March weighed an average of 498 g; Females average 478 g.

In adult wood pigeons of the nominate form , the front back and shoulder area are slate-gray to gray-brown, the rest of the trunk is blue-gray on top. The goiter area and breast are diffuse grayish wine-red, the color becomes lighter towards the abdomen and is very light gray in front of the under tail-coverts. The head is blue-gray. On the sides of the neck and on the nape of the neck there is a green, metallic shimmering band from top to bottom, then a white spot only on the sides of the neck and then again a shiny purple band on the sides of the neck and nape. The inner arm covers , the large hand covers and the thumb wing are slate gray. The outer flags of the outer arm covers are predominantly white and the outermost arm covers are completely white; this creates a conspicuous white band on the upper wing. The hand wings are black-gray, the outer flags of the 1st to 9th hand wings have a narrow, sharply defined, white border, this border is only diffuse on the 10th (outermost) hand wing. The arm wings are predominantly ash gray. The control feathers are broadly blue-gray on the upper side at the base, followed by a diffuse, light gray subterminal band and a wide black end band.

The beak is pink to red at the base, orange to yellowish at the end with a horn-colored tip. The fleshy membrane over the nostrils is white. The legs and toes are light to dark red. The iris is light yellow.

Outwardly, the sexes are very similar. Females show a less strong red color on the breast and the white spots on the sides of the neck are slightly smaller. The downy dress of the nestlings is light straw-colored and hair-like. The green, red and white neck markings of the adult animals are missing in the youth dress and the contour feathers have narrow, light red-brownish hems. The neck markings are already developed in the juvenile moult of the small plumage, depending on the hatching date of the young bird, it usually appears between August and December of the year of birth. The iris is yellowish white in juvenile birds.

Vocalizations

The Reviergesang is a dull, hoarse and not very loud cooing that begins with a "rúhgu, gugu". This is followed by a five-syllable “rugúgu, gugu” repeated 2 to 13 times, but mostly 4 to 5 times, and finally a short “gu” at the end. The courtship call is a shorter "grrugu-rú".

Mauser

The juvenile moult is a partial moult and begins as early as the sixth or seventh week of life. It includes the small plumage as well as part of the arm wings and the hand wings. The hand swing moult begins with the innermost (first) hand swing and is interrupted in November or December, by then the inner five or six hand swing are usually renewed. The small plumage moult continues through the winter. The swinging moult continues in the spring or starts again from the beginning with the innermost swinging hand. The control feathers do not molt until they are four to six months old.

The moult of the adult birds occurs as a full moult , it begins in March or April and lasts until November or December.

distribution and habitat

The species colonizes large parts of the Palearctic from North Africa, Portugal and Ireland to the northeast to western Siberia and to the southeast via Asia Minor to the Tian Shan and Kashmir . It occurs in almost all of Europe and is only missing here in the extreme north from around 67 ° N.

Wood pigeons inhabit wooded landscapes of all kinds; however, individual trees or bushes may be sufficient for a settlement. If these are also missing, the animals breed z. B. in dunes, on salt meadows or in grain fields on the ground. Broods in populated areas have been known in Europe since at least 1821; today wood pigeons breed in avenues, parks and in cemeteries, often as far as the center of cities. The breeding sites must not be too far away from suitable foraging habitats; In Europe today these are mainly agricultural areas such as grassland and fields, but also the forests and green spaces used for breeding. The foraging flights can be limited to the nest environment, depending on the offer, but can also take place regularly over distances of 10 to 15 kilometers.

Systematics

A work on the internal systematics of the genus Columba and thus also on the closest relatives of the wood pigeon is apparently not yet available.

Currently five subspecies are mostly recognized, two of which are endemic to islands . There are flowing (clinical) transitions between the three continental subspecies, generally the animals become lighter to the east and the wing length becomes somewhat smaller. The distribution information is based on Glutz von Blotzheim and Bauer:

- Columba palumbus palumbus Linnaeus , 1758 : The nominate form populates most of the distribution area.

- C. p. casiotis ( Bonaparte , 1854) : The breeding area includes southeastern Iran, Afghanistan and Kashmir . The subspecies is slightly paler on the upper side than the nominate form, the white neck side spot of the nominate form is smaller and brownish.

- C. p. iranica ( Zarudny , 1910) : breeding bird in most of Iran except in the southeast, also in the adjacent part of Turkmenia . The subspecies mediates between the nominate form and C. p. casiotis .

- C. p. azorica Hartert , 1905 : endemic to the Azores . The subspecies is overall darker than the nominate form.

- C. p. maderensis Tschusi , 1904 : Endemic to Madeira . The subspecies is also generally darker than the nominate form.

The separation of the wood pigeons of North Africa as a separate subspecies C. p. excelsa is not generally recognized.

nutrition

Foraging takes place both on the ground and, in contrast to the other Central European pigeons, to a considerable extent on trees and bushes. The species is sociable when foraging for food outside of the territories and often forms small schools here. As with most species in the family, the diet is almost entirely vegetable. Acorns , beechnuts and grain seeds are the main foods in Europe . In addition, however, depending on the local offer, a very wide range of other vegetables are eaten, including green leaves, buds and flowers of various plants, berries and other fruits, tubers (e.g. potatoes or beets), and oak galls . Urban populations can feed primarily on bread and other baked goods. Animal food is occasionally added, most obviously scale insects and caterpillars and pupae, few other arthropods and earthworms. Apparently to cover the need for lime, small molluscs , i.e. mussels and snails, are sometimes eaten.

Reproduction

Wood pigeons are sexually mature in May or June of the year following their birth. The animals live predominantly in a monogamous seasonal marriage, at least in non-migrant populations, apparently, permanent marriages also occur. The territory is established by the males. Only the area around the nest is defended against conspecifics as a territory. The size of the district is very variable depending on the settlement density; If there is a very high population density, the area can only consist of the tree used for breeding. The courtship begins in March or April, but often in winter in urban populations. With the start of egg-laying, courtship activity decreases, but due to the very long breeding season, courtship animals can often be observed until September. In addition to the frequent calls, courtship also includes male courtship flight. The male flies steeply upwards from a high waiting area 20 to 30 m and often claps his wings loudly several times. Then it glides down with horizontally stretched wings and spread tail. This courtship flight is often repeated two to five times and then extends in a large arc through the area and, in very small areas, beyond.

The male offers nesting sites, the final selection is made by the female. The nest is mainly built on trees or large shrubs, whereby the privacy is particularly important. Therefore, conifers are mostly preferred in spring and autumn. The species is very adaptable when it comes to choosing its breeding grounds; where larger trees are missing, the nests are also placed low in hedges and if these are also missing, wood pigeons breed on the ground, especially on islands. In cities, the nests are also built on buildings in niches or on projections.

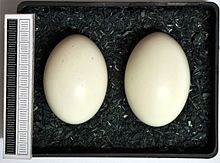

The nest is a thin platform with a central hollow and is built from thin, mostly bare branches. New nests are often so translucent that the eggs can be seen from below. Usually the male brings material to the nest site, which is then built by the female. Nest building usually takes 6–13 days, sometimes just 2 days. The nests are often used repeatedly, occasionally the nests of other bird species are used as a nest base. In Central Europe, eggs are laid as early as the end of February, but usually only begins in April or May. Two annual broods are common, three occur sporadically. The last clutches are usually started by mid-September, rarely even in October. The clutch consists almost exclusively of 2 eggs, rarely just one egg. The eggs are white, glossy and almost elliptical. Eggs from Belgium measure 40.3 × 29.6 mm on average, series from other areas of Western and Central Europe showed very similar values.

The breeding season is 16-17 days. The nestling period lasts on average 28-29 days, with around 35 days the young birds are fully capable of flight. As with all pigeons, the nestlings are fed crop milk , but from day one they also receive the plant-based food that the parents eat. Their share increases with the age of the nestlings, plant parts make up about 8% of the nestling food on the third day of life of the nestlings and already about 80% in the third week. The time of the last feeding is very variable, but is usually between the 26th and 40th day of life. In subsequent broods, often only one parent feeds the young birds.

In studies in Halle and London , only 33% of all breeding attempts fledged. If the broods were successful, an average of 1.7 juveniles fledged in Halle , 1.5 juveniles each in London and Cambridge . The major part of clutch losses is caused by corvids . The clutches of early broods in particular are endangered by predators , as the adult birds here often search for food for so long due to the still relatively poor availability of food that the nest is temporarily unguarded. The majority of nestling losses, on the other hand, are apparently mainly due to lack of food and bad weather; predation probably plays a lesser role here.

hikes

Wood pigeons are, depending on their geographical distribution , resident birds or short-distance migrants, the tendency to migrate increases from west and south-west to north-east. British and Mediterranean populations are almost entirely resident birds. In the north-west of Central Europe (Belgium, the Netherlands, north-west Germany) around 30 to 55% of the birds migrate. The wood pigeons of Scandinavia, Northeast Europe and Switzerland are almost all migratory birds.

The species pulls the day and migrates all day, in Central Europe in autumn, however, mainly from around 6:30 a.m. to midday and preferably on clear days with a light tail wind. The animals migrate in swarms. High mountains and larger parts of the sea are reluctant to fly over, so that strong migratory concentrations occur in straits, along coasts, over mountain passes and the like. The withdrawal from the breeding areas in eastern and northern Europe takes place from mid-September and lasts until the beginning of November with a peak of the main path and migration from early to mid-October.

In Falsterbo , an average of 203,000 migrants were observed in the period 1973 to 1990. There the relocation begins hesitantly in the second decade of September, reaches a clear climax in mid-October and ends in the second decade of November. In one day a maximum of 124,000 migrating wood pigeons were observed there.

European birds overwinter mainly in the Atlantic dominated Western Europe and in the Mediterranean area. In Europe, the edge of the wintering area is limited to the north and east by the 0 ° C and 2.5 ° C January isotherms , the size and distribution of the winter stocks fluctuate considerably depending on the food supply and the weather. The migration begins in February, rarely at the end of January, at the same time the occupation of the breeding grounds begins. The train culminates in March and April and runs out in early May. In Central Europe, the breeding grounds are mostly occupied in early to mid-March. The northernmost breeding areas are reached around mid-April.

Natural enemies

The main enemy of adult wood pigeons is the goshawk in western and central Europe, and the horned eagle in southern Europe . When collecting prey remains of the goshawk, the wood pigeon is usually one of the five most frequently represented species due to its wide distribution and frequency. For example, the wood pigeon is in fourth place in the hawk bag lists from Uttendörfer from all of Central Europe from around 1895 to 1938, and in first place in more recent collections in Schleswig-Holstein with 17.4% of all prey. Other birds of prey such as the peregrine falcon and sparrowhawk and rarely the buzzard prey on the species less frequently . Among the Central European owls, the eagle owl in particular regularly eats the wood pigeon, and the eagle owl can also be one of the main prey animals in the region.

Mortality and age

No information is available on the average age of wood pigeons living in the wild. According to different calculations, the mortality in the first year of life in Great Britain and the Netherlands is 46 to 70%, that of adult individuals between 35 and 46%. In addition to natural enemies and various diseases, severe winters in particular can cause high regional losses, but the main cause of the high mortality in large parts of Europe is likely to be heavy hunting. The three oldest wood pigeons known to date were ringed in Great Britain and Switzerland and were 15 years and 11 months, 16 years and 4 months and 17 years and 8 months old.

Hunting

The species is hunted intensively in many countries; according to estimates, at least 4 to 5 million wood pigeons were killed annually in Europe in the 1970s. In Germany, the annual shooting varied between 1990 and 2005 between 655,000 and 917,000 pigeons. The reporting of the kills is not specific to the species in all federal states, so it may also include possible unintentional false kills of stock pigeons , Turkish pigeons and lovebirds , whereby the Turkish pigeons are also subject to hunting law. The vast majority of the pigeons shot are wood pigeons. In Germany, the pigeons can be hunted from November 1st to February 20th. The German hunting range has decreased by almost 50 percent in the last ten years, with strong regional differences. In some federal states, old pigeons enjoy grandfathering, exceptions are only allowed to prevent damage. The distance in 2015/16 was 509,700 individuals, the lowest level in ten years. The share of North Rhine-Westphalia has remained unchanged for 10 years at 65 percent of the German annual route, followed by Lower Saxony with 25 percent. The total share of all other federal states is only 10 percent.

The Swiss hunting route has remained unchanged for ten years at around 1,000 wood pigeons, which were shot across the country without any priorities. The Austrian hunting route in the 2015/16 hunting year was 15,350 wild pigeons. In some federal states, besides Turkish pigeons, lovebirds are also hunted. A differentiation of the species in the hunting statistics is not carried out, as in Germany, so it is worthless for a population determination.

Existence and endangerment

The species is one of the most common breeding birds in Europe. BirdLife International estimates the world population roughly at 30 to 70 million animals and the European population at 18 to 34 million individuals. The European population was stable between 1970 and 1990 and increased slightly between 1990 and 2000. The population in Germany, for example, was estimated at 2.2 to 2.6 million pairs in 2008, making the species the eleventh most common breeding bird species overall and the most common non-singing bird species this year. The stock is stable here.

According to the IUCN 's Red List of Threatened Species, the wood pigeon is not endangered worldwide ( least concern ).

literature

- E. Bezzel: Compendium of the birds of Central Europe. Nonpasseriformes - non-singing birds . Aula, Wiesbaden 1985, ISBN 3-89104-424-0 .

- Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim and Kurt M. Bauer : Handbook of the birds of Central Europe . Volume 9., 2nd edition, AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1994, ISBN 3-89104-562-X , pp. 64-97.

- L. Svensson, K. Mullarney and D. Zetterström: Der Kosmos Vogelführer . Kosmos, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-440-12384-3 , pp. 214-215.

Web links

- Videos, photos and sound recordings for Columba palumbus in the Internet Bird Collection

- Age and gender characteristics (PDF; 1.9 MB) by J. Blasco-Zumeta and G.-M. Heinze (Eng.)

- Feathers of the wood pigeon

Individual evidence

- ↑ UN Glutz v. Blotzheim and KM Bauer: Handbook of the birds of Central Europe . Vol. 9, 2nd edition, AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1994, ISBN 3-89104-562-X , pp. 66-67.

- ↑ L. Svensson, PJ Grant, K. Mullarney and D. Zetterström: The new cosmos bird guide . Kosmos, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-440-07720-9 , p. 200.

- ↑ UN Glutz v. Blotzheim and KM Bauer: Handbook of the birds of Central Europe . Vol. 9th, 2nd edition, AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1994, ISBN 3-89104-562-X , pp. 68-69.

- ^ For an overview of previous studies, see SL Pereira, KP Johnson, DH Clayton and AJ Baker: Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Sequences Support a Cretaceous Origin of Columbiformes and a Dispersal-Driven Radiation in the Paleogene. Systematic Biology 56; 2007: pp. 656–672 full text, online doi : 10.1080 / 10635150701549672

- ↑ a b The wood pigeon on Avibase

- ↑ a b c U. N. Glutz v. Blotzheim and KM Bauer: Handbook of the birds of Central Europe . Vol. 12, Part II., AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1991, ISBN 3-89104-460-7 , p. 64.

- ↑ UN Glutz v. Blotzheim and KM Bauer: Handbook of the birds of Central Europe . Vol. 9th, 2nd edition, AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1994, ISBN 3-89104-562-X , p. 80.

- ↑ UN Glutz v. Blotzheim and KM Bauer: Handbook of the birds of Central Europe . Vol. 9th, 2nd edition, AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1994, ISBN 3-89104-562-X , p. 82 and the literature cited there.

- ^ L. Karlsson (Ed.): Birds at Falsterbo. Lund, 1993, ISBN 91-86572-20-2 , pp. 46 and 129.

- ↑ UN Glutz v. Blotzheim and KM Bauer: Handbook of the birds of Central Europe . Vol. 9th, 2nd edition, AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1994, ISBN 3-89104-562-X , pp. 70-74.

- ↑ O. Uttendörfer : The diet of the German birds of prey and owls. Reprint of the 1st edition from 1939, Aula-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1997, ISBN 3-89104-600-6 , pp. 56 and 335.

- ^ V. Looft & G. Biesterfeld: Habicht - Accipiter gentilis . In: V. Looft and G. Busche: Vogelwelt Schleswig-Holstein, Vol. 2: Birds of prey. 2nd edition, Karl Wachholtz Verlag, Neumünster 1990, ISBN 3-529-07302-4 , pp. 101-115.

- ↑ UN Glutz v. Blotzheim and KM Bauer: Handbook of the birds of Central Europe . Vol. 9th, 2nd edition, AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1994, ISBN 3-89104-562-X , pp. 82-83 and the literature cited there.

- ↑ UN Glutz v. Blotzheim, KM Bauer: Handbook of the birds of Central Europe . Vol. 9th, 2nd edition, AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1994, ISBN 3-89104-562-X , p. 83.

- ↑ Staav, R. and Fransson, T. (2008): EURING list of longevity records for European birds. online, accessed October 29, 2009

- ↑ German Hunting Protection Association e. V .: DJV Handbuch 2005. Mainz: pp. 325–327

- ↑ Annual route wild pigeons , accessed on August 5, 2017

- ↑ Detailed species account from Birds in Europe: population estimates, trends and conservation status (BirdLife International 2004) (PDF, English)

- ↑ Sudfeldt, C., R. Dröschmeister, C. Green Mountain, S. Jaehne, A. & J. Mitschke choice: Birds in Germany - 2008. DDA, BfN, LAG VSW, Münster, 2008 S. 7th full text, PDF

- ↑ Columba palumbus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2009. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2009. Accessed on March 8 of 2010.