Rougemont Castle

Rougemont Castle , also Exeter Castle , is a castle in the city of Exeter in the English county of Devon . It was built into the north corner of the Roman city wall. Its construction began in or about 1068 after the Exeter rebellion against William the Conqueror . In 1136 it was besieged by King Stephen's troops for three months . A bailey , of which little is left today, was added in the course of the 12th century.

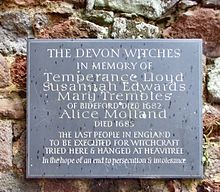

The castle is featured in Shakespeare's play Richard III. mentioned in connection with the visit of the same king to Exeter in 1483. Devon's county court resided in the castle no later than 1607, and the three Devon Witches - the last of England's citizens to be executed for witchcraft - were tried here in the 1680s.

All of the buildings within the castle walls were demolished in the 1770s to make way for the new courthouse, to which additional wings were added in 1895 and 1905. Because of its function as a courthouse, the interior of the castle was not open to the public until the court moved to another location in 2004. The entire property was sold to a contractor whose stated goal is to convert it into "a Covent Garden in the South West".

The castle is named after the red rock found in the hill that was used in the construction of the original buildings. The most important part of it that has survived to this day is the Norman gatehouse . It is enclosed on three sides by Rougemont Gardens and Northernhay Gardens . These are public parks that are now maintained by Exeter City Council.

Construction and early history

After the Norman conquest of England in 1066, Gytha Thorkelsdóttir , mother of the defeated King Harald , lived in Exeter and this may have led to the city becoming a center of resistance against William the Conqueror. Another source of discontent could have been Wilhelm's request to increase the city's traditional annual tribute from £ 18. After the citizens of Exeter refused Wilhelm's request that they swear allegiance to him, he marched with his troops outside the city gates and besieged it for 18 days until it surrendered.

The citizens of Exeter had been able to withstand Wilhelm's siege thanks to the city wall, which was first built by the Romans and then extensively repaired by King Æthelstan around 928 . Although the siege ended with the abandonment of the city, Wilhelm ordered that a castle be built within its walls to secure his position. The place chosen for this was the highest point of the city wall, in its northern corner on a volcanic rock.

The construction of the castle was left to King Wilhelm Baldwin FitzGilbert , who was made castellan among other honors . A deep moat and an inner wall were built between the northwest and northeast sections of the city wall, resulting in an almost square, fenced-in area with a side length of about 182 meters. The Domesday Book of 1086 reports that 48 houses in Exeter have been destroyed since the king came to England - this has been interpreted by historians to mean that many houses in this location have been demolished for the new castle. A large stone gatehouse, which has been preserved to this day, was built on the moat on the south side of the enclosure. It shows elements of Anglo-Saxon architecture , such as B. long and short corners and windows with double-triangular lintels, suggesting that it was built very early by Anglo-Saxon builders at the behest of the Normans. In this early phase, a palanke was probably attached to the wall , although soon two corner towers were built at the points where the wall met the city wall, of which the western one - often incorrectly called "Æthelstan's Tower" - still exists. The palank was soon replaced by a brick curtain wall . The remains of this wall show that it was integrated into the restored city wall, but not into the gatehouse, which indicates that it was built from the former to the latter. Another early addition was the construction of a protective barbican over the city side of the drawbridge . There is evidence that the castle was attacked before it was completed. The evidence is both physical - in the form of repairs to Æthelstan's Tower - and documentary - in the form of a report by Ordericus Vitalis of an attack on Exeter in 1069.

At the beginning of the 12th century, a chapel dedicated to St. Mary was built within the castle walls. It had four benefices and is said to have been built by William de Avenell, a son of the castle builder Baldwin FitzGilbert; de Avenell also established a priory in nearby Cowick (a suburb of Exeter).

The Siege of 1136 and Later History

In 1136 Baldwin de Redvers took the castle in the course of his rebellion against King Stephen . Although Stephen's army moved quickly to besiege the castle, Redvers managed to withstand the siege for three months until the water supply, which was ensured by a well and probably also by a rainwater cistern, collapsed. It is possible that an eastern tower as a counterpart to the Æthelstan Tower no longer exists today because it was undermined during the siege at the time. The discovery of a short section of a roughly built tunnel to this part of the castle wall around 1930 is associated with this event. It is also likely that the barbican was captured and destroyed at that time.

On a hill north of the castle is a small, circular earthwork . It is now called Danes Castle , but from the 12th to the 16th centuries it was called New Castle . It was thought to have been the outskirts of Rougemont Castle, which was built to defend its north side, but after the 1992 excavations it is believed to have been built by Stephen's army during the siege.

After the attack by Stephen's troops, it became apparent that the advancing technology of siege equipment spurred the construction of a bailey in the 12th century. This consisted of a wall and an external moat that ran from the eastern city wall on the north side of Bailey Street - where the only remaining section of the wall is to this day - to the western city wall near the current city museum, where parts of the backfilled moat are located were discovered during restoration work in 2009.

Richmond! When last I was at Exeter,

The mayor in courtesy show'd me the castle,

And call'd it Rougemont: at which name I started,

Because a bard of Ireland told me once

I should not live long after I saw Richmond.

(dt .: Richmond When I was last in Exeter!

Showed me the mayor of politeness the castle,

and called it Rougemont: The name by which I started,

Because a bard of Ireland told me once

I should not live more long after seeing Richmond. )

Source: Richard III. from Shakespeare

The castle continued to be repaired from time to time until the beginning of the 14th century; the last documented repair of the defenses took place in 1352. From around 1500 the original gateway was no longer used, the entrance was closed and a subsequent arched passage was built. In the far north corner of the castle there was a sideline gate under a large tower and a drawbridge over the moat outside the castle wall. These were demolished in 1774 and today there is no trace of them to be found.

Although the castle was always officially called "Exeter Castle", the more common name "Rougemont Castle" first appeared in a local record in 1250. It refers to the red color of the rock on the hill and the color of the walls that were built from those rocks. King Richard III visited Exeter in 1483 and in Shakespeare's Richard III. the bard reminds the king of the premonition of his death when he is shown the castle and the "Rougemont" confuses "Richmond" with "Richmond". The castle is said to have been badly damaged during the second Cornish uprising of 1497 when Perkin Warbeck and 6,000 Cornishmen invaded the city, and around 1600 it was said to show "gaping cracks and an elderly constitution".

17th to 20th century

In 1607 a courthouse was built within the castle walls and in 1682 and 1685 the four "Witches of Devon" were tried here before they were executed in Heavitree. They were the last delinquents in England to be executed for witchcraft; a plaque near the gatehouse commemorates these events. The well-known cartographer and choreographer John Norden created a floor plan of the castle and its surroundings in 1617. She shows u. a. the recently built courthouse, the chapel, the location of the draw well, the northern side gate and probably also the destroyed walls of a rectangular donjon on the north-eastern castle wall.

The castle did not play a crucial role in the English Civil War , although in 1642 Parliament allowed Exeter to use £ 300 of public money to fortify the city and repair the castle. Despite the at least four artillery batteries in the castle, the town fell to the royalists in 1643 and then again to the parliamentarists in 1646 . During the war, the gatehouse was used as a prison at times.

In 1773 all the buildings within the castle walls were demolished and replaced with a limestone courthouse in the Palladian style . The local architect Philip Stowey had designed it and James Wyatt had corrected the design. At that time the entrance gate from the beginning of the 16th century was replaced by a new one, which was built of improved stone and had a simulated portcullis . This gate still serves its purpose today. The courthouse was expanded westward in 1895, creating offices for the new county court. In 1905 another neo-Palladian wing was added to the east.

A section of the castle wall between the gatehouse and the eastern city wall threatened to collapse in 1891, and despite attempts to repair it, it collapsed in October of the same year. The dilapidated part of the wall was the one around the round tower on the north floor plan from 1617. It was speculated that after this tower was demolished (at an unknown point in time) the wall was closed again with inferior quality masonry. After the Marienkapelle and the other buildings were torn down at the end of the 18th century, a porter's house was built near the new castle entrance. This porter's house was threatened by the unsafe castle wall, and while the wall was being repaired, excavations in its floor revealed several skeletons that were believed to have been buried around the chapel. Thomas Westcote wrote around 1630 that the chapel was "in ruins" and a 1639 document mentions that Bishop Joseph Hall was asked to identify the area around the chapel "for the funeral of inmates who die in prison."

Other notable occurrences in the castle included: B. the first ascent in a hot air balloon in Exeter by a certain Monsieur St. Croix from the courtyard in June 1786 and on May 15, 1832 the first annual exhibition of the Devon Agricultural Society.

21st century

Until 2003, the castle's intact Georgian buildings remained the seat of royal power in the county and housed the Exeter Royal Court and the County Court. Hence the castle was one of the least known and most inaccessible places in town, and few residents had ever set foot beyond the entrance gate; the castle was never open to tourists. Difficulties in accessing the steep castle grounds for disabled people then became a major problem and in 2004 a new courthouse was built in the new Exeter judicial district. After the Exeter City Council failed to buy the property, the Royal Courts sold it to GL50 Properties in early 2007, whose manager said, “Rougemont Castle is an amazing building that we are going to transform into a Covent Garden in the south west of England. "

Today the castle is protected from alteration as a Scheduled Monument and its most important parts were designated by English Heritage as historical buildings I. or II *. Grade listed. A statue that EB Stevens created in 1863 of Hugh Fortescue, 1st Earl Fortescue , stands in the courtyard: It is considered a II degree monument. As the responsible planning body, Exeter City Council has expressed an interest in the future of the castle. She expressed her view that the castle, however used in the future, should be reasonably accessible to the public and integrated as a key element in the city's cultural quarter. The historical significance and quality of the property and the buildings should be respected and at least the impressive courthouse should be available for public events, even if the buildings were put to commercial use. As an example of the new use, the band Coldplay gave a benefit concert in the courtyard in December 2009 during their Viva la Vida tour .

In 2011 the former courtroom 1 was reopened as "The Ballroom" with its arched windows down to the floor. The toilets were built into the former prison cells. Courtroom 2 was opened as "The Gallery" with an area of 150 m². To this end, 12 new apartments were set up within the castle walls.

Individual references and comments

- ^ A b LSH announce the sale of Exeter's landmark building Rougemont Castle . Lambert Smith Hampton. January 12, 2007. Archived from the original on June 16, 2007. Retrieved on April 9, 2012.

- ^ A b William George Hoskins: Two Thousand Years in Exeter . Philmore, Chicester 2004. ISBN 1-86077-303-6 . Pp. 24-27.

- ^ William George Hoskins: Two Thousand Years in Exeter . Philmore, Chicester 2004. ISBN 1-86077-303-6 . P. 23.

- ↑ Sometimes it is described as a "volcanic cone" (Laming / Roche), sometimes as a "volcanic rock" (Perkins), sometimes as a "volcanic wall" (Mellor).

- ↑ Deryck Laming, David Roche: Devon Geology Guide - Permian Breccias, Sandstones and Volcanics . Devon County Council. 2009. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- ^ John W. Perkins: Geology Explained in South and East Devon . David & Charles, Newton Abbot 1971. ISBN 0-7153-5304-7 . P. 123.

- ^ A b c d Hugh Mellor: Exeter Architecture . Phillimore, Chichester 1989. ISBN 0-85033-693-7 . P. 77.

- ^ ET Vachell: Exeter Castle, its Background, Origin and History in Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association . No. 98 (1966). P. 335.

- ^ ET Vachell: Exeter Castle, its Background, Origin and History in Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association . No. 98 (1966). P. 336.

- ^ A b E. T. Vachell: Exeter Castle, its Background, Origin and History in Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association . No. 98 (1966). Pp. 335-338.

- ^ ET Vachell: Exeter Castle, its Background, Origin and History in Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association . No. 98 (1966). P. 341.

- ^ ET Vachell: Exeter Castle, its Background, Origin and History in Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association . No. 98 (1966). Pp. 339-340.

- ^ Rev. W. Wykes-Finch: The Ancient Family of Wyke of North Wyke, Co. Devon in Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association . Booklet XXXV (1903). P. 391.

- ^ ET Vachell: Exeter Castle, its Background, Origin and History in Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association . No. 98 (1966). Pp. 340-342.

- ^ A b E. T. Vachell: Exeter Castle, its Background, Origin and History in Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association . No. 98 (1966). Pp. 342-343.

- ^ Exeter Excavation Committee: Report on the Underground Passages in Exeter in Proceedings of the Devon Archaeological Exploration Society . Issue 1. Edition 4 (1932). Pp. 192, 195, 197.

- ^ A b William George Hoskins: Two Thousand Years in Exeter . Philmore, Chicester 2004. ISBN 1-86077-303-6 . P. 31.

- ↑ Beverley. S. Nenk: Danes Castle . Pp. 203-204. 1993. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ ET Vachell: Exeter Castle, its Background, Origin and History in Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association . No. 98 (1966). P. 344.

- ^ MFR Steinmetzer: Archaeological Investigation and Building Recording at the Royal Albert Memorial Memorial Museum, Exeter . Exeter Archeology. January 2011. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ↑ Richard III., Act IV, scene 2 . Open source Shakespeare. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ↑ a b Nikolaus Pevsner, Bridget Cherry: The Buildings of England . Chapter: Devon . Penguin Books, Harmondsworth (1952) 1989. ISBN 0-14-071050-7 . P. 400.

- ^ Point "A" on the north floor plan from 1617.

- ↑ Alexander Jenkins: The History and Description of the City of Exeter . P. Hedgeland. Pp. 217-218. 1806. Retrieved September 14, 2015. A copy of the wood carving mentioned in Jenkins' text is from the Devon County Council 's Etched on Devon's Memory website ( March 3, 2016 memento on the Internet Archive ). April 2012, to see.

- ^ David Cornforth, Interesting and Famous Visitors to Exeter. . Exeter Memories. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ↑ Percy Addleshaw: Bell's Cathedrals: The Cathedral Church of Exeter . G. Bell and Sons Ltd. Pp. 92-93. 1921. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ↑ Inaccurately, the floor plan appears in George Oliver's History of the City of Exeter from 1861 as "built around 1624".

- ↑ Detailed Result: EXETER CASTLE . Pastscape. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ Eugene A. Andriette: Devon and Exeter in the Civil War . David & Charles, Newton Abbot 1971. ISBN 0-7153-5256-3 . P. 72.

- ^ A b Central Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan . Exeter City Council. Pp. 29-44. August 2002. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015. (PDF file)

- ^ Sir JB Phear: Recent Discoveries at the Castle, Exeter in Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association . Book XXIII (1891). Pp. 318-321.

- ^ David Cornforth: First balloon ascent . Exeter Memories. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ Devonshire: The First Annual Exhibition of the Devon Agricultural Society . In: Sherborne Mercury . May 21, 1832. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ David Cornforth: Rougemont Castle . Exeter Memories. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ Castle gig for Coldplay's Martin . BBC News. December 2, 2009. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ The Times, London February 28, 2011.

Web links

Coordinates: 50 ° 43 ′ 32.4 " N , 3 ° 31 ′ 48.2" W.