St-Victor (Marseille)

The Abbey of Saint-Victor de Marseille was in the early 5th century by John Cassian - near the tombs of (360 to 435) martyrs of Marseille founded. Among these graves was named Viktor von Marseille , † 303 or 304. The abbey has been one of the centers of Catholicism in southern France , almost without interruption .

The founder was a monk in Bethlehem , a wandering monk in Egypt , the deacon of John Chrysostomos (344 / 49-407) in Constantinople , a priest in Antioch or Rome , was in the year 416 in what was then Massilia , where Proculus , the bishop of Marseille , gave him it commissioned to found a monastery on the south bank of the Lacydon , the old port . Benedictine monks lived here from the end of the 10th to the 18th century .

history

Antiquity

During the Roman Empire , the area around the abbey was a quarry; a grotto in this quarry later became a Christian necropolis , which may have been built around the remains of the martyrs Volusianus and Fortunatus . According to tradition, Johannes Cassianus is said to have built a monastery around this grotto (today the Notre-Dame des Confessions chapel ). Historically, the existence of a monastery at this time is not guaranteed, but an early Christian sanctuary has been archaeologically proven since the 5th century

Viktor of Marseille, who was crushed under a millstone for refusing to renounce Christianity and who gave the abbey its name, was an officer in the Thebaic Legion , according to Eucher , Archbishop of Lyon in the 5th century consisted of Christians, many of whom died during the persecutions of Diocletian and Maximian in 303.

middle Ages

From 750 to 960, Saint-Victor was the residence of the Bishops of Marseille. Charlemagne transferred the salt law, customs and anchorage fees in the port of Marseille to the abbey. Ludwig the Pious and Lothar I confirmed these privileges.

At the end of the 9th or beginning of the 10th century, the abbey was destroyed by Saracen raids. Honorary II, Bishop of Marseille since 948 and relative of the first Vice Count of Marseille , had the monastery rebuilt. His relative Pons I, bishop from 977, continued this work.

In 977 Saint-Victor became a Benedictine monastery , and in 1005 the monks elected Wilfredus (or Guilfred) as the first abbot . Pope John XVIII († 1009) granted the abbey a number of important privileges that established the monastery’s wealth and were subsequently confirmed by many popes. From 1020 to 1047 the Catalan monk Isarn was abbot of Saint-Victor; under whose rule the power of the monastery grew so much that Pope Benedict IX. consecrated the church in 1040, and Isarn canonized after his death on September 24, 1047 .

On September 28, 1362 Abbot Guillaume de Grimoard was elected Pope, he took the name of Urban V to. After his death in Avignon in 1370, his body was transferred to Saint-Victor.

Giulio de Medici was abbot of Saint-Victor from 1570 to 1588 . Historians suspect him of looting the abbey's library - the inventory of which was recorded in the 12th century. Jules Mazarin , abbot since 1655, is also suspected of having appropriated some of the books.

Dissolution of the abbey

On December 17, 1739, Pope Clement XII ordered the abolition of the abbey. In 1794 the monastery and two churches were robbed, the relics burned, gold and silver used to strike coins, and the buildings converted into a straw warehouse and prison.

20th century

In 1936 the church was raised to the rank of a minor basilica . In 1963, the city of Marseille and the Ministry of Culture began a complete renovation of the church, which was included in the 1997 list of Monuments historiques .

Church building

The church, whose architecture mixes Romanesque and Gothic elements, was built between the 12th and 14th centuries. The oldest of the lower parts are the tower of Isarn , with the entrance hall and including in the crypt that are available Chapel of St.. Andreas . The ship was built in the 13th century under Hugo von Glazinis . Its epitaph is in the crypt. The choir was built under Pope Urban V in the 14th century. His tomb, which disappeared during the French Revolution , was also located here.

In the crypt under the western half of the church, remains of the ancient necropolis and the early Christian sanctuary can still be seen. It houses an important collection of early Christian sarcophagi and evidence from the Middle Ages, such as the tomb slab of Abbot Isarn from the 11th century. The names of the sarcophagi generally refer to the saints whose relics are said to have been found in them.

The monastery used to be outside the city, hence the well-fortified architecture. The monastery buildings were demolished during the French Revolution and until the mid-19th century.

Upper Church

| A- entrance hall in the tower of the Isarn | 1- sarcophagus with strigil pattern and cross (late 4th century) |

| B- Chapel of the Holy Sacrament | 2- Early Christian altar table (5th century) |

| C- ship | |

| D- right aisle (south side) | 3- Abraham's sarcophagus or the handing over of the keys to Peter (late 5th / early 6th century) |

| E- left aisle (north side) | 4- Statue of the seated Madonna and Child , copy of a Catalan sculpture from the 11th century. 5- Statue of Saint Victor by Richard Van Rhijn, erected in 2007 |

| F- transept | 6- Painting of the Virgin Mary by the Marseille painter Michel Serre (1658–1733) 7- Reliquary 8- Painting of St. Joseph with the baby Jesus by the Marseille painter Dominique Papety (1815–1849) 9- Reliquary |

| G-choir | 10- Altar 11- Location of the vanished tomb Urban of V. |

| H- sacristy | |

| I- Chapel of the Holy Spirit | 12- baptismal font |

| J entrance to the crypt |

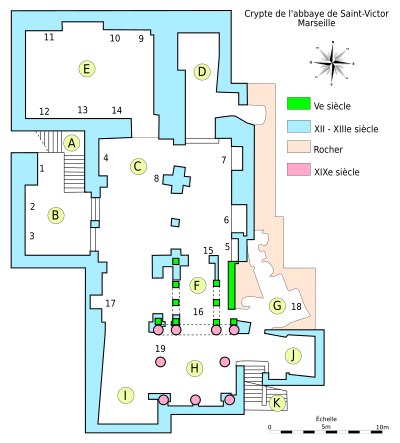

crypt

| A- entrance stairs | |

| B- Chapel of St. Maurontus (Bishop of Marseille around 780) | 1- Four of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus . Fragment of a sarcophagus from the end of the 4th century that actually represents the apostles gathered around Christ 2- Sarcophagus of the Companions of St. Mauritius (late 4th century) 3- Sarcophagus of St. Mauritius (late 4th century) - Sarcophagus of St. Maurontus (2nd century), in the altar opposite the stairs on the south side of the chapel, is missing from the plan. Pagan sarcophagus of Julia Quintina, used for the tomb of St. Maurontus is said to have been reused |

| C- Isarn chapel and the space between the chapels of St. Andrew and Notre Dame de Confession | 4- Grave slab of Abbot Isarn (2nd half of 11th century) 5- Epitaph for the abbess (?, "Religiosa") Eusebia (probably 6th century), including sarcophagus of St. Eusebia (early 4th century), originally the grave of a man from the senatorial class according to the medallion 6- Sarcophagus of the Companions of St. Ursula (1st half of the 5th century) 7- Epitaph for Hugo von Glazinis (died 1250) 8- Fresco from the 13th century depicting monks building or workers in the quarry |

| D- Chapel of St. Andreas | Originally the entrance to the early Christian sanctuary. An X-shaped wooden cross was later kept here, on which Andrew is said to have been crucified. It was destroyed during the French Revolution |

| E- Old sacristy of the crypt, today lapidarium | 9- Epitaph of Fortunatus and Volusianus (2nd or 3rd century). The interpretation of the fragmentary inscription is controversial: for some it is about Christian martyrs, for others about drowned seafarers 10- Sarcophagus of Christ enthroned (5th century) 11- Sarcophagus with lambs and deer (5th century) 12- Sarcophagus of the Anastasis (resurrection of Jesus Christ) (end of 4th century) 13- Lid of an ancient sarcophagus, which was reused in the 5th century for a "noble Eugenia" 14- Antique pagan epitaph (2nd half of 2nd century) |

| F- Martyrdom or Chapel of Notre Dame de Confession | During excavations in 1960, a twin grave carved out of the rock from the 4th century with two skeletons was discovered, which was interpreted as a martyr's grave, possibly of Fortunatus and Volusianus, but this is doubted by science 15- Black Madonna Notre Dame de Confession, Wooden statue from the Middle Ages, is especially venerated at Candlemas (French: Chandeleur, February 2nd) 16- The sarcophagus of St. Johannes Cassianus (1st half of the 5th century), grave of a child 17- sarcophagus of St. Chrysanthus and Daria (end of the 4th century), depicting the resurrection of Christ |

| G- Chapel of St. Lazarus | Here the veneration for the biblical Lazarus , according to legend the first bishop of Marseille, mixed with the veneration for Lazarus, bishop of Aix in the 5th century, who is said to have been buried here. The face above the 11th century column to the right of the entrance is supposed to represent him. In the back of the chapel, parts of the late antique burial chamber can be seen behind a grille. 18- Sarcophagus of the Innocent Children (2nd century), pagan children's sarcophagus |

| H- atrium, on the site of the early Christian sanctuary. | Nine ancient columns still present here were removed from 1801–1802, three of them are still in Marseille: Monument to Homer at the intersection of Rue Moustier / Rue d'Aubagne, Pest column at the corner of Rue des Trois Mages / Rue de la Bibliothèque, antique column at the museum Borély 19- mosaic fragment (5th century) |

| I- Chapel of St. Blasius | |

| J- Chapel of St. Hermes | Sarcophagus of St. Hermes and Adrian (not on the plan). Cassis stone sarcophagus from the 6th century depicting the handing over of the keys to Peter |

| K- Age access to the crypt |

See also

Web links

- Official website of the Saint-Victor Abbey, with 360 ° panoramas of the interior and the crypt, accessed on January 13, 2016

literature

- Michel Fixot, Jean-Pierre Pelletier: Saint-Victor de Marseille. Étude archéologique et monumentale (= Bibliothèque de l'Antiquité tardive . No. 12 ). Brepols Publishers, Turnhout 2009, ISBN 978-2-503-53257-8 (327 pages).

- Michel Fixot, Regis Bertrand, Jean Guyon: Saint-Victor de Marseille. Le guide . Mémoires millénaires, Saint-Laurent-du-Var 2014, ISBN 978-2-919056-36-1 (155 pages).

Individual evidence

- ^ Fixot: Saint-Victor de Marseille, le guide. 2014, pp. 17 and 36

- ^ Fixot: Saint-Victor de Marseille, le guide. 2014, p. 17

- ^ Fixot: Saint-Victor de Marseille, le guide . 2014, p. 23

- ^ Fixot: Saint-Victor de Marseille, le guide. 2014, p. 59

- ^ Fixot: Saint-Victor de Marseille, le guide. 2014, p. 77

Coordinates: 43 ° 17 '25 " N , 5 ° 21' 56.3" E