Battle of Hamel

The Battle of Hamel took place during World War I on July 4, 1918 on the Western Front in the Somme section east of Amiens . After a combined artillery and infantry attack with tank and air support, the Allies succeeded in snatching the village of Hamel from the German troops within 93 minutes. The new tactic used was conceived by General John Monash and carried out by Australian infantrymen together with US troops, with support from the British 5th Tank Brigade. With the hitherto customary methods of attack on the western front, the path to success would have taken several weeks and would have required four times as many victims.

prehistory

After the failure of the first phase of the German spring offensive , there was a brief, quiet break in the fighting on the Somme sector. During the German advance on Amiens at the end of March 1918, the Australian 11th Brigade (Brig.-Gen. JH Cannan ) was among the first units to stop German advances and repel the attack at Morlancourt . On April 4, the German troops occupied Le Hamel and advanced on Villers-Bretonneux .

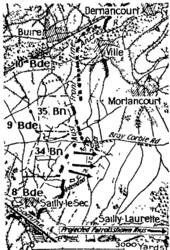

In the second battle of Villers-Bretonneux (April 24-27, 1918) the Australian 13th Brigade (Brig. Gen. TW Glasgow ) and the 15th Brigade (Brig. Gen. HE Elliott ) succeeded in the city of Villers-Bretonneux after the Germans had ousted the British 8th Division (Lieutenant General William Heneker ) from it. The section was transferred to the 3rd Australian Division (Major General John Monash), which in the association of the British 4th Army took the protection of the front line northeast of Villers-Bretonneux, where they used the tactic of "soft infiltration" against the Germans from April . The essence of the new tactic was to infiltrate the troops and equipment under cover of darkness close enough to the enemy line to deploy heavy weapons against the target areas and then use tanks as cover for the suddenly attacking infantry. Between May 4th and 9th, the Australian 9th Brigade ( Brig. Gen. Rosenthal ) attempted to break into the German positions at Morlancourt, which were held by the 237th Reserve Infantry Regiment of the 199th Division . The 10th Brigade (Brigadier General Walter McNicoll ) secured the left flank and the 8th Brigade (Col. Edwin Tivey ) of the Australian 5th Division secured the right flank. Terrain was gained, but the breakthrough to the Bray-Corbie road was not successful. On May 11, the positions around Morlancourt were assigned to the Australian 5th Brigade (Brig. Gen. EF Martin ), which consisted of the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th Battalions. Subsequently, on May 13, the Germans launched a partial attack against the 5th Brigade with 200 men in order to regain the lost positions, but were repulsed by May 14. After the failed counterattack, the Germans brought the 107th Division forward as a replacement and began a heavy bombardment on the Australian lines on May 15. On June 10th further fighting took place around Morlancourt. The Australian 7th Brigade (Brig.-Gen. EA Wisdom ) was able to storm the Morlancourt - front ledge, which previously ruled the village of Sailly-Laurette .

When the general German offensive shifted to the central section of the Western Front in June 1918, the Allies in the Somme section no longer asked themselves where the Germans would attack next, but instead prepared their own counter-offensive that would ultimately end the war .

planning

In late June, General Sir Henry S. Rawlinson's British 4th Army began planning a series of limited counter-attacks to improve their position and prepare for the counter-offensive ( Hundred Days Offensive ) planned for late summer . An obvious first target was the German promontory west of Hamel. The village's location on a hill nearly twenty kilometers east of Amiens enabled German artillery observers to direct fire on British communication lines in the city. The conquest of Hamel and the surrounding area would also secure the defense on hill 104 - the highest point on the plateau near Villers-Bretonneux.

John Monash, since June 1, 1918 Lieutenant General and Commander of the Australian Corps and a former engineer from Melbourne, was an advocate of the use of combined arms, including the participation of tanks. The tank gun, however, was still in the early stages of development. Many crews were untrained and their driving skills were mostly unskilled. The early tank models have had disappointing results in previous battles. In the summer of 1918, the introduction of the new Mark V tank - a faster maneuverable and better armed type, in contrast to the Mark IV - promised the possibility of a less lossy success. The many deaths in the battles, a deadly influenza epidemic and a decline in recruitment rates also brought infantry replacements to a standstill on the Western Front. Monash relied on a strategy in which the troops were only sparingly exposed to enemy fire. On June 21, he submitted to his superior, General Rawlinson, a meticulously worked plan for setting up a limited attack in the Hamel section at dawn. General Rawlinson immediately agreed to the request and on June 27th informed the II. US Corps (Major General George W. Read ) in his area of command that the participation of American soldiers in the attack at Hamel was desired. Initially, two brigades from the Australian 3rd and 4th Divisions were selected to lead the attack on Hamel and two more were deployed as reserves by the Australian 2nd Division. Four companies were selected by the American Expeditionary Forces , which were loaned to the 33rd Division (Maj. Gen. George Bell ). Large parts of the 26th US Infantry Brigade (131st and 132nd Infantry Regiments) were used on the front lines for the first time. Early June 30th, one month after arriving in France, C Company of the 131st Infantry Regiment (Col. Joseph B. Sanborn ) joined the 42nd Australian Battalion from Queensland, while E Company joined the South Australian 43rd Battalion reinforced. Companies A and G of the 132nd Infantry Regiment (Colonel Abel Davis) had to report to the 13th Battalion from New South Wales and the 15th Battalion from Queensland.

The planned breakthrough of the positions of the German XI. Army Corps ( Kühne Group ) should be carried out with the usual infantry attack, but with considerable support from tanks. The German 13th Division had recently moved to Hamel after having rested for a month, while the 43rd Reserve Division had taken up positions in and north of Hamel two weeks earlier. The 202nd Reserve Infantry Regiment held Hamel itself, while the 201st and 203rd RIRs extended the line to the north. In the section of the 13th Division, Infantry Regiment No. 55 held the "pear ditch" and part of the Bois de Vaire, Infantry Regiment No. 13 the rest of the forest from Vaire to the south, where Infantry Regiment No. 15 continued south to the Roman road in Position was.

Monash wanted to attack as early as possible in order to avoid the daylight and also to reduce the enemy's view and thereby protect his own troops as long as possible from the enemy defensive fire. Infantry, artillery, tanks and planes had to work closely together on an attack section over 2 kilometers deep. During the preparation, Monash let the soldiers from the different tank and infantry divisions mix and make friends, each infantry battalion painted its insignia on the tanks assigned to them. This not only promoted camaraderie, but later also made movements easier, as each battalion would be better off advancing together using a color code. Monash also asked for 18 more planes to bomb Hamel, as well as older flying machines with loud engines to distract attention from the noise of the preceding tanks.

Allied planning for the British 4th Army was carried out in strict secrecy. Two days before the start of the counter-offensive, Monash had the Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes' visit to be postponed so that preparations for the upcoming attack would not be disrupted. During a visit to the headquarters of the Second US Corps, the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces , General John J. Pershing , learned of Rawlinson's instructions to use American troops in the attack on Hamel. He immediately advised General Read not to participate in the company. Pershing believed it would be better if American troops stayed together rather than fighting as scattered units among the Allied armies. On the morning of July 3, Pershing's order to withdraw the American units reached six of the ten companies that had been committed to the Australian corps. The American troops reacted mostly with disappointment, the majority obeyed the order dutifully. The withdrawal of the Americans at this late point in time destroyed Monash's meticulous plan, as the reduction in Australian units would have meant postponing the attack in general. This would have halved the strength of the 16th Battalion and the crew of the 11th Brigade would have dropped from 3,000 to 2,200 soldiers.

course

The day before the attack

The day before the battle, at 4:00 p.m., Monash received an order from 4th Army headquarters to release all Americans from his area of command to the Australian 4th Division. At 5:00 p.m. Monash insisted that the remaining four companies were essential for the attack. Unless Rawlinson insisted on obeying Pershing's orders to withdraw all Americans by 6:30 p.m., he intended to proceed with the preparations without changing the schedule. Monash said, "It would be more important to maintain the trust of the Americans and Australians in one another than to keep an army commander in command." Rawlinson knew that Monash was a talented officer and decided to cover his corps commander, if not Field Marshal Douglas Haig himself who would cancel the decision by 7:00 p.m. Haig, who was privy to the controversy, called shortly before 7:00 p.m. and resolved the matter with a laconic sentence: "The attack must be started as prepared, even if some American departments disembark before the start of the attack at midnight."

Monash, who wanted to start the opening campaign before daylight, went to bed to monitor the attack early enough. In the early morning hours of July 4th, his artillery commander Brigadier WA Coxen saw him pacing nervously at headquarters. That night at 10:30 p.m. the British tanks Mark V and Whippet from Fouilloy and Hamelet began to drive up to their meeting room 0.8 km behind the front. The 42nd Battalion was enjoying a hot meal in the trenches as it watched 144 Allied aircraft drop more than 1,100 bombs on Hamel - while the tanks, camouflaged by the darkness and the engines of the aircraft noise, began their journey from the protected positions in Forests and orchards in their attack positions. Between midnight and 1:45 a.m. the infantry followed the tracks of the tanks, which had crossed their own opened wire barriers. Monash's plan was to conquer the forests at Hamel and Vaire and the uplifting spur behind them on a 6-kilometer front, which would require proceeding to a depth of 3 kilometers.

The attack

On July 4th at 3:02 am, the operations of the Australian corps on the Villers-Bretonneux and Corbie line against Hamel and the surrounding area began. The British 3rd Tank Brigade had arrived with 63 Mark V and Mark A tanks from the Hamelet - Fouilloy line and opened the advance. About 7000 men of the 2nd and 4th Australian divisions, plus 1000 infantrymen from the United States attacked with the support of 85 attack aircraft. On the German side, the section of the XI. Army Corps hit. The entire front of the 13th Division (Major General Rudolf von Borries ) and the left wing of the 43rd Reserve Division (Major General Wilhelm Knoch) were affected . The German positions in the forest of Vaire and south of the village of Hamel and the so-called "pear trench" were connected by narrow rows of trees. The forest of Hamel was the northernmost of the two and lay on a low plain that rose to a hill on which the Bois de Vaire stood. To the west of the forest area, on the other side of the road that connected Hamel with Villers-Bretonneux, the Germans had dug a kidney-shaped trench, which the Australians called the “Vaire Trench”.

At 3:10 a.m. the main artillery strike followed with 313 howitzers and 326 field guns, more than 100 Vickers machine guns opened the barrage . The far-reaching artillery of the neighboring British III. Corps (Lieutenant-General Richard Butler ) in the north and the French XXXI. Corps (General Paul-Louis Toulorge) in the south supported the attacks on both wings of the attacking Australians. The barrage acted 183 meters in front of the attacking troops and was then extended to 549 meters forward. A few weeks ago, Monash had ordered that explosives, smoke grenades and poison gas projectiles should be fired at this time, a tactic which should force the German defenders to regularly expect barrages, the smoke should simulate the presence of gas. At 3:14 a.m., the barrage moved further forward and the infantry followed behind a wall of smoke that was reinforced by shell impacts on the calcareous soil. The use of poison gas was dispensed with, which enabled the troops to advance under the protection of the mist veil without great losses. During the attack, the attack aircraft of the 8th Squadron (RAF) and 3rd Squadron (Australian Flying Corps) flew over enemy lines and bombed enemy infantry, weapons and transport. The 205th Squadron (RAF) bombed the enemy depots and bivouacs that had already been identified the previous days.

Four Australian brigades led the attack under the command of the General Staff of the Australian 4th Division (Major General Ewan Sinclair-McLaglan ):

- 4th Brigade, Brig. Gen. Charles Henry Brand

- 6th Brigade, Brig. Gen. John Gibson Paton

- 7th Brigade, Brig. Gen. Evan Alexander Wisdom

- 11th Brigade, Brig. Gen. James Harold Cannan

- 3rd Tank Brigade, Brig. Gen. Anthony Courage

Many tanks that had been assigned to the 4th Brigade had lost their way in the dark and did not arrive in time for the first attack. The attack of the 15th Battalion of the 4th Brigade was supported by only three tanks. The 16th Battalion, supported by the 4th Mortar Battery, attacked in the middle of the 4th Brigade, with the 15th Battalion on the left and the 14th in reserve. The infantry followed the barrage at a distance of 70 meters. Although the barrage was accurate, some sheaves hit the seam between the 4th and 11th Brigades, effectively wiping out a platoon of the 43rd Battalion. Further south, 12 soldiers of the 15th Battalion were killed and 30 men injured in a similar incident. The American C Company under Captain Carroll M. Gale, which accompanied the Australian 42nd Battalion, followed behind the barrage and advanced 100 meters every three minutes. These formations came under exploding shells within 75 meters without suffering any losses. Troops of the E Company in the 15th Battalion, however, lost 12 dead and 30 wounded because their own grenades missed their target. The battalion's B Company received heavy fire from the edge of the forest and the northern part of the Vaire Trench and lost its commander. The attack hit three German defensive positions in the forest of Vaire and Hamel and in front of the village of Hamel. The German defense was in the hands of about 5500 men, from the Reserve Infantry Regiment No. 202, the Infantry Regiment (1st Westphalian) No. 13, Infantry Regiment (2nd Westphalian) No. 15 and the Infantry Regiment (1st Westphalian) No. Regiment (6th Westphalian) No. 55.

The forests of Hamel and the Bois de Vaire quickly fell into the hands of the Australian 4th Brigade. The task of conquering Hamel was assigned to the four battalions of the 11th Brigade and the 11th Mortar Battery. The 43rd Battalion, in the middle of the brigade, was assigned to take the village itself, while the 42nd Battalion and half of the 44th would flank the Notamel Forest on the left and the other half of the 44th Battalion on the right. The 41st Battalion was kept in reserve. Here the main strike was supported by 27 tanks, excluding those tanks that supported the efforts to conquer the so-called "pear trench". The operators of the heavy Lewis machine guns fired mostly from the hips, which kept the German machine gun nests down. Although they suffered heavy losses themselves, they bought enough time for a machine-gun platoon to dig around two enemy machine-gun nests. At the Notamel forest, German resistance was initially strong, as the enemy positions were well positioned and interlocking fire struck the attackers. A company of the 43rd Battalion was briefly stopped at the edge of the forest by an intact German machine gun before a tank rolled over the position; farther north, the 42nd Battalion had successfully reached its positions with precision fire.

The southern flank of the attack front stretched along the Roman road to the east. On the right side of the 4th Brigade, parts of the 6th Brigade - the 21st and 23rd Battalion - had been given the task of taking this area with direct support from the artillery. They were reinforced by the 25th Battalion, which had been separated from the 7th Brigade in order to put out the enemy fire on the flank. As soon as the attack started, the 21st Battalion advanced on the left flank and, supported by tanks and barrages, overcame the relatively light German resistance. The 23rd Battalion also advanced almost without loss, although it encountered greater resistance. On the other hand, the 25th Battalion suffered heavy losses and lost almost two entire platoons when German machine gun positions fired into their ranks. When the Germans started a counterattack, an emergency call was made for artillery support and another platoon was called in to contain the enemy, and finally the 25th battalion secured all targets north of the Roman road. The tanks rolled forward 1,100 meters and were instrumental in breaking the German will to further counterattacks.

In the northern sector near Morlancourt, the Australian 15th Brigade (Col. Lt. JC Stewart) launched a deception attack at 3:10 a.m. against the German 52nd and 232nd Reserve Infantry Regiments, which covered part of the German trench line around Ville- sur-Ancre could conquer and hold. The attack began with artillery fire from the Australian 5th Division (Major General JT Hobbs ). A company of the 58th Battalion attacked along the Ancre at a width of 700 meters, while two companies of the 59th Battalion attacked a 500-meter line of German outposts. As a result, the Germans began to secure the position on the heights of Morlancourt by counter-attacks. A battalion of the 247th Reserve Infantry Regiment of the 54th Reserve Division was dispatched to a counterattack, which was crushed by fire from the Australian and British artillery alone.

Finale

After the Australians and Americans took the village of Hamel, they immediately began building the defensive positions. The clearing of the forests of Vaire and Hamel was completed by 7:00 a.m. The tanks remained on the battlefield in support until 5:30 p.m. and then were withdrawn, taking some of the wounded with them. Throughout the night of July 5th, German snipers fired on the Allied line. The Germans continued to obstruct the Australian troops around Hamel, made small air strikes and launched a bombardment to prepare for a counterattack. The German counterattack then took place on the evening of July 5th at 10:00 p.m. After phosgene and mustard gas grenades were fired, about 200 men from Reserve Infantry Regiment 201 advanced and broke into the sector of the Australian 44th Battalion near Le Hurleux. The Germans captured a dozen Australian carriers but could not get reinforcements because British artillery fired their lines of retreat.

When the 44th Battalion rallied to counterattack, it was reinforced by the Americans from the 43rd Battalion. On July 6, at 2:00 a.m., the two battalions attacked the cut off German troops. The German storm troops held out, checked the situation and then withdrew, the trapped stretcher carriers were freed. The four American companies that were deployed at Hamel were withdrawn from the after the battle and returned to their main regiments. Monash personally thanked Major General Bell for the American effort, while Pershing gave explicit instructions that US troops should not be used in a similar manner without his consent.

Losses and consequences

The offensive on Hamel ended in a tactical victory for the Allied arms. All the goals set had been achieved in 93 minutes, only three minutes longer than Monashs had calculated. Despite fears from the Australian infantry, all but three of the British tanks had reached their targets.

Allied losses amounted to 1,380 dead or wounded. The Australian troops alone had lost 1,062 men, 800 of whom were killed. The two brigades of the Australian 2nd Division (Major General Sir Charles Rosenthal), which were temporarily attached to the Australian 4th Division, lost 246 men. The American casualties numbered 176 men, including 26 dead. Five of the Allied tanks were damaged during the attack but could later be repaired. The losses among the British tank crews amounted to 13 dead or wounded. A large amount of British equipment captured by the Germans when they captured Hamel in April was also recovered. The Australian 15th Brigade had suffered a further 142 casualties during its diversionary attack north of Morlancourt.

The German casualties amounted to 2,000 men, 1,600 of whom were prisoners, plus 177 machine guns and 32 mortars. Only one month later, the maneuver was repeated on a larger scale in the battle of Amiens on August 8, 1918, the victory there heralded in the words of General Erich Ludendorff the " Black Day of the German Army ", the final defeat of the German Empire.

literature

- John Hughes-Wilson: Hamel 4th July 1918: The Australian & American Triumph , Unicorn Publishing, Uniform Press London 2019, ISBN 978-1-911604-42-6

- John Laffin: The Battle of Hamel: The Australians' finest victory , Kangaroo Press; 1st edition (1999) ISBN 978-0-86417-970-8

- Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean: The Australian Imperial Force in France during the Allied Offensive, 1918 . Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918. Volume VI. Sydney, New South Wales 1942: Angus and Robertson. OCLC 41008291. (page 280-335) https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1416794

- George W. Browne: Divisional records of the American expeditionary forces in Europe , compiled from official sources by GW Browne and Rosecrans W. Pillsbury, Overseas Book Company 121, 19211851-1930.