Battles between Lexington and Concord

| date | April 19, 1775 |

|---|---|

| place | Lexington , Concord , Lincoln , Menotomy and Cambridge in the Province of Massachusetts Bay , colony of the Kingdom of Great Britain , now USA |

| output | American victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Province of Massachusetts Bay Militia , Minutemen |

|

| Commander | |

|

Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith, Major John Pitcairn , Captain Walter Laurie, Brigadier General Hugh Percy, Earl Percy |

Captain John Parker , Colonel James Barrett , Brigadier General William Heath |

| Troop strength | |

| 900 in the first expedition (Smith): 250 at Lexington Green (Pitcairn), 115 at Concord Bridge (Laurie), additional 1000 men reinforcement for the return to Boston (Percy), all figures estimated | 75 at Lexington Green (Parker), 500 at Concord Bridge (Barrett), 4000 at the end of the day (Heath), all figures estimated |

| losses | |

|

74 dead, 26 missing, 174 wounded |

50 dead, 5 missing, 39 wounded |

Northern Campaign

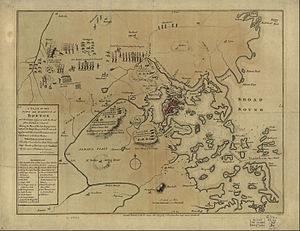

The battles at Lexington and Concord were the first battles of the American Revolutionary War . They were held on April 19, 1775 in Lexington , Concord , Lincoln , Menotomy and Cambridge in Massachusetts . The skirmishes mark the beginning of the armed conflict between Britain and the thirteen colonies .

Summary

Approximately 700 professional soldiers (regulars) of the British Army under the command of Lieutenant Colonel had Francis Smith ordered to military stocks to seize or destroy in Concord from the one according to the report militia were stored Massachusetts. Weeks earlier, the American rebels had received a warning of the upcoming British search operation through espionage and had brought almost all supplies to safety. The night before the battle, the rebels had also learned details of the British plans and quickly passed them on to the militia.

The first shots were fired in a skirmish in Lexington during the British advance. However, the militia were outnumbered and fled. Other militiamen fought three companies of royal soldiers at the Old North Bridge in Concord. The British units disbanded their formation after a heated battle and fled.

Over the next few hours, more Minutemen were added, inflicting heavy losses on the British soldiers returning from Concord. Smith's expedition was reinforced on the return to Lexington by soldiers under General Hugh Percy and released from their difficult situation. The two British divisions with a total of 1700 soldiers marched back towards Boston and came under heavy fire. When they arrived in Charlestown , they finally made a successful tactical retreat.

The British failed to achieve the secrecy and speed necessary for successful action in enemy territory. In addition, they failed to destroy a significant amount of weapons and supplies. However, most of the soldiers managed to return to Boston unharmed. The occupation of the surrounding area by the Massachusetts militia coincided with the beginning of the siege of Boston .

The battles are in America known as the "shot heard 'round the world" ( " shot heard round the world ") and have been in Ralph Waldo Emerson's Concord Hymn described. They are regularly recreated at the Minute Man National Historical Park .

background

The British army , which disparagingly of Americans "Redcoats" ( " redcoats ") or "Lobster Backs" ( "lobster backs") was called, was stationed in Boston since 1768 and was naval forces and British Marines strengthened to enforce a series of legislative measures . These were mutually referred to by the Americans as " Intolerable Acts " (intolerable laws) or by the British as "Coercive Acts" (coercive measures) . Governor General Thomas Gage was still not succeeded in controlling regain over the area outside of Boston, where because of the Massachusetts Government Act (Government Massachusetts law) to tensions between the majority of so-called colonial patriots and a minority of loyalists had come. Gage now planned to defuse tensions by withdrawing their weapons from the British colonists' militias in a series of small, quick and surprising actions. These efforts led first to a successful British operation and then to a number of failures, which, however, still ended lightly. These actions were called powder alarms . Gage saw himself as a freedom-loving and sought to separate his duties as governor of the colony and as general of an occupying army. As a result of the vehement rejection of the Coercive Acts by the American side, the general had even asked the British government to suspend the laws temporarily. However, his application was denied. Edmund Burke described the problematic relationship between Gage and the Massachusetts Colony in Parliament as follows: "An Englishman is the least qualified person on earth to convince another Englishman to take up slavery." ( Edmund Burke )

Instructions from Dartmouth and orders to Gage

On April 14th Gage received instructions from the British Home Secretary William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth , to disarm the population and arrest the leaders of the insurgents. For the execution of this order he received only rough guidelines and considerable freedom of design.

On the morning of April 18, the day before the battle, Gage sent a mounted patrol of around 20 soldiers into the surrounding area to intercept mounted messengers. This patrol behaved differently than usual, staying on the road after dark, questioning travelers about the whereabouts of Samuel Adams and John Hancock . The unintended consequence of this was that many local residents became nervous and prepared. The Lexington militia, in particular, met in the early evening hours before they received news from Boston. In the dark, a farmer mistook the British patrol for his like-minded friends and asked if they had heard when the British were coming. This earned him a blow on the head with the flat side of a saber.

Lt. Col. Francis Smith received orders from Gage on the afternoon of April 18 that he should not read until he was out with his troops. They contained the order that he should march, with the utmost care, to Concord, where he should confiscate and destroy all military supplies. But at the same time he should make sure that his soldiers do not plunder the residents or damage private property. Gage apparently interpreted his own orders to mean that he was not issuing a written order to arrest rebel leaders.

Successful espionage of the patriots

With the exception of Paul Revere and Joseph Warren , the leaders of the rebels had already left Boston on April 8th. They had heard of Dartmouth's secret instructions to Gage from sources in London long before they were delivered to Gage. Samuel Adams and John Hancock had fled to Lexington to live with relatives of Hancock, where they believed they were safe.

The Massachusetts militia had indeed stored weapons, gunpowder and supplies in Concord, but the patriots had heard British officers watching the streets into Concord. They instructed local residents to put the supplies aside and distribute them to other nearby towns.

The Patriots had learned of the imminent action on April 19, although it had been kept secret from all British officers and men directly involved. There is reason to believe - albeit unproven - that the origin of the information lies in the relationship between Warren and Gage's American-born wife Margaret.

On the night of April 18, 1775, between 9 p.m. and 10 p.m., Warren informed William Dawes and Paul Revere that royal soldiers were about to take boats from Boston to Cambridge and continue to take the road to Lexington and Concord. Warren's report suggested that the British venture's most likely targets would be the capture of Samuel Adams and John Hancock. They were less concerned about the soldiers' possible march to Concord, since the supplies had already been brought to safety, but feared that their leaders in Lexington had not heard of the impending action and were thus in danger. Revere and Dawes should warn them and alert other patriots in the surrounding areas.

Dawes took the horse to the south overland route over the Boston Neck and over the Great Bridge (Great Bridge) to Lexington. Revere first gave instructions to send a signal from the tower of the Old North Church to Charlestown and then traveled on the northern waterway. He crossed the Charles River in a rowboat and passed the British warship HMS Somerset, which was anchored, unnoticed . Crossings were forbidden at this hour, but Revere made it safely to Charlestown and rode into Lexington. He avoided the British patrol and then warned almost every house along the way. These events went down in history as the midnight ride . The warned people and the patriots of Charlestown in turn sent more horsemen north.

After arriving in Lexington, Revere, Dawes, Hancock and Adams discussed the situation with the assembled militiamen. They concluded that the forces withdrew from Boston were too numerous to arrest just two men and that Concord was the real target. The Lexington men sent messengers in all directions, only Waltham was not notified for reasons unknown. Revere and Dawes continued on their way to Concord. At 1:00 am, they met Samuel Prescott . However, the three ran into the British patrol, and so only Prescott managed to warn Concord. More mounted messengers were sent from Concord.

Revere and Dawes set off a flexible messaging system that had been carefully developed in the months preceding the Powder Alert . In addition to mounted messengers carrying messages, bells, drums, warning shots and trumpets were used so that patriots in other locations could be called quickly to raise their militia as soon as the redcoats left Boston. These early warnings were instrumental in assembling sufficient numbers of the militia to inflict casualties on British soldiers the following day. Samuel Adams and John Hancock were first brought to what is now Burlington and later to Billerica .

British Army and Marines move away

The 700 British soldiers, led by Lieutenant Colonel Smith, came from Gage's elite light infantry and grenadiers .

The British made their men ready to march at 10 p.m. on the evening of April 18, and at 11 p.m. they marched to their boats. The British march to and from Concord was terrible for the soldiers from start to finish. The boats were so fully loaded that there was no room to sit, and in Cambridge they had to disembark in waist-high water at midnight. After a long stop to unload the equipment, the regulars set off at around 2 a.m. on their 27 km long march to Concord. They were heavily laden with water bottles, haversacks, muskets, and equipment, and wore wet, muddy shoes and damp clothing. As they marched through what was then the Menotomy , signal noises announced that they had lost the element of surprise. At about three o'clock in the morning, Colonel Smith sent Major Pitcairn ahead with six companies of light infantry to march on to Concord. At around 4 a.m., however, he anticipated, albeit a little late, and made the decision to send an embassy to Boston with a request for reinforcements.

The battles

Lexington

When the advancing British troops under the command of Pitcairn arrived in Lexington at sunrise on April 19, 1775, about 60 militiamen, led by Captain John Parker, came from Buckman Tavern , waited in the village green and watched the arriving soldiers. About 40 to 100 spectators stood along the street. Parker told his militiamen not to back down or shoot and let the army march past unmolested.

Instead of turning left to Concord, Lieutenant of the Marines Jesse Adair at the head of the three companies independently decided to first turn right to protect his own flank and then let two companies march onto the village meadow themselves. The men then ran to the Lexington militia and also lined up in the line, shouting "Huzzah!" Major Pitcairn himself came forward, waved his sword and shouted, “Dissipate, you rebels; be damned, throw away your weapons and disperse! ”Captain Parker ordered his men to disperse, but some did not hear him, some walked away very slowly, and no one laid down his arms. Both Parker and Pitcairn ordered not to shoot, but someone fired a shot.

Some witnesses of the Regulars reported that the first shot was fired by an American spectator behind a hedge or corner of the tavern's building. Some Lexington militiamen testified that a British mounted officer fired first. Both agreed that none of the foot soldiers facing each other had shot.

Eyewitnesses reported multiple shots from both sides before the regulars began firing volleys without orders. Some of the militiamen initially believed that the regulars only fired powder without bullets, but then realized the gravity of the situation and returned fire. Pitcairn's horse was hit twice. The regulars carried out a bayonet attack. Captain Parker saw his cousin Jonas get stabbed. Eight Massachusetts men were killed and ten wounded. The British reportedly had only one slightly wounded man. The eight Americans killed, the first military casualties of the American Revolution , were John Brown, Samuel Hadley, Caleb Harrington, Jonathon Harrington, Robert Munroe, Isaac Muzzey, Jonas Parker, and Ashahel Porter. Jonathon Harrington, fatally wounded by a bullet, crawled back home and died on the doorstep. Prince Estabrook, a black slave, served in the Lexington militia and was also wounded in combat on the village meadow.

The infantry under Pitcairn could no longer be controlled by the officers. They shot in different directions and tried to break into houses. Then the main division marched into town and Colonel Smith restored order. The British regrouped, fired a victory shot, gave three cheers and continued on to Concord.

Concord

The older Concord militiamen advised caution until reinforcements arrived from the surrounding areas. The middle-aged men wanted to stay and defend the place. The younger Minutemen men wanted to go east and attack the British army from higher ground. As the regulars approached, each of the three groups acted on their own terms. The Minutemen watched from a hill as Smith directed the light infantry against them. Then they marched back into town. The older men and middle-aged men had moved up a hill in the village and were discussing what to do next while the Minutemen came up to them, pursued by the regulars. Now the Lincoln militia arrived and took part in the discussion. The older men prevailed. Colonel Barrett ordered a retreat from the village and led the men across the Old North Bridge to a hill about a mile outside the village. From there they could watch the movements of the British troops.

The regulars follow Gage's orders

Smith's soldiers were divided into a variety of units to carry out Gage's orders. One company of light infantry secured the southern bridge, and seven companies of light infantry secured the Old North Bridge near the militiamen. Of these seven companies, four companies were dispatched to search Barrett's property about two miles across the bridge, and two other companies from the 4th and 10th Regiments of Foot continued to guard the bridge.

The grenadiers searched the place for military supplies. Pitcairn threatened a patriot leader with his pistol until he led him to three buried cannons. Then Pitcairn paid him breakfast. The grenadiers also burned some cannon teams they found in the village, and when the fire spread to the adjacent building, residents and soldiers formed a chain of fire together to save the building. About 100 barrels of flour and 250 kg of balls were thrown into the mill pond. The bullets were recovered the following day.

Barrett's house had been an arsenal for the previous weeks, but now there were few weapons left. These had also been hidden. The troops sent there marched more than anyone that day, and they found nothing but a breakfast, which some soldiers asked for from Mrs. Barrett.

North Bridge

Colonel Barrett's militiamen saw the smaller units directly in front of them and, after collecting an opinion , determined they were marching to a flat hill about 300 yd (274 m ) from the Old North Bridge. This property belonged to Major John Buttrick, leader of Barrett's Minutemen units, and was also their parade ground. A British company was still there, but withdrew to the bridge without a fight when Barrett's men approached.

Five full Minutemen companies and five other militia companies now occupied the hill. More men were constantly added, in the end there were about 500 in total, who faced the light infantry companies of the 4th, 10th and 43rd Regiments of Foot under the command of Captain Laurie. Laurie had a total of 115 men.

Barrett ordered the militiamen to line up in a long line of two along the river, then called the militia commanders for further consultation.

It was at this point that they saw smoke from the burning cannon teams rising over Concord, and many thought the Regulars had begun to burn the place down. Colonel Barrett ordered the men to reload their weapons, but not fire without enemy fire. Then he ordered the advance. The two British companies guarding the Old North Bridge were ordered to retreat across the bridge. An officer began tearing down planks from the bridge. Major Buttrick yelled at the regulars to stop destroying the bridge. They were on his property and he probably thought the bridge belonged to him and his men too. The Minutemen and the rest of the militia advanced on the light infantry just as professional soldiers would have.

The young, inexperienced Captain Walter Laurie then had a tactical maneuver that was unsuitable in this situation. He ordered his men to line up behind the bridge for "street fires", at right angles to the river. This formation is suitable for dropping many balls into a narrow street between buildings, but not for an open path behind a bridge. Now there was confusion when the regulars retreating across the bridge had to avoid their comrades who were forming and then join them in the same way. A lieutenant in the rear recognized Laurie's mistake and ordered the flank to be flanked. But he came from a different company than the men under command, and so only three obeyed. The rest of them tried to carry out their superior officer's orders. The opponents faced each other like a big "T", with the horizontal bar being the militiamen and the vertical bar being the regulars on and behind the bridge.

A shot was fired and this time both sides agreed that it was from the ranks of the regulars. Two more regulars shot, followed by the close group at the very beginning, before Laurie could stop them. Two of the Acton Minutemen, including their captain Isaac Davis in the unfortunate center of the lines, were hit and killed instantly, and another four, including the Piper, were wounded. However, the Massachusetts militia advanced in formation. They waited in discipline to fire until the order to fire was given by Major Buttrick when they were 50 yards (46 m ) from the British and separated from them by the Concord River. Four of the eight British officers on site were hit by the volley. At least three regulars were killed and nine wounded. Now the British were not only outnumbered but also found themselves outmaneuvered. They ignored their officers, left the wounded and fled.

After the fight

The patriots were amazed at their success. Some advanced, others withdrew. A man hacked a wounded British soldier in the head with a hatchet, exposed his brain, scalped him without killing him. Barrett eventually regained order and decided to split up his troops. He sent the militia back up the hill and sent Buttrick and his Minutemen across the bridge to take up a defensive position behind a stone wall on a hill.

Lt. Col. Smith, the leader of the British expedition, was in the area and heard the gunfire just a short time after Laurie asked for reinforcements. Smith gathered two companies of grenadiers to lead them to the Old North Bridge himself. On the march, three companies without formation ran towards the soldiers from the bridge. Now Smith was concerned about the four companies that had marched across the bridge to Barrett's property. They were now cut off. Then he saw the Minutemen behind the wall. He made the soldiers stop and only went in with the officers to get an idea.

A Minuteman later wrote that they probably could have killed any officer before them, but they didn't because they didn't have the appropriate orders. During the tense ten minutes that followed, a madman walked through the ranks of the two groups to sell cider . Smith decided to march back into town. He hoped the four missing companies would make their way.

These men rushed back from Barrett's house, fearful of being cut off. They passed the premises of Barrett's militia and the previous battlefield unharmed. They saw their dying scalped comrade on the bridge, and they passed the Minutemen without loss. So all units of the regulars had returned to the village by 11:30 a.m. And now even after a small skirmish and in excess, the New Englanders only returned fire after provocation. The British decided not to do so. The British Army left Concord around noon.

The march back

From Concord to Lexington

Smith sent scouting patrols toward a ridge that ran along the way back. He wanted to protect his troops from the approximately 1,000 Americans who were in the area. The ridge ended near Miriam's Corner, a small bridge junction about a mile outside Concord. An American fired first, and the British regulars turned and fired a volley. In the firefight that followed, two regulars were killed and possibly six wounded. The Americans got away with it. After crossing the bridge, Smith again sent scouts sideways.

Nearly 500 militiamen gathered a mile past Miriam's Corner in the woods on Brooks Hill. Smith's forces at the head stormed up the hill to drive the Americans out, but the Americans did not retreat. Meanwhile, the bulk of Smith's troops continued their march down the road towards the Brooks Tavern, where they fought a single militia company. Some Americans were wounded or killed in the process. Smith ordered his troops on Brooks Hill to withdraw. He and his men reached Lincoln over a small bridge.

Soon afterwards they were met at a bend in the road ("The Bloody Curve") by 200 men who had hidden behind trees and walls on an embankment and thus set up a successful ambush. Other militias attacked from across the street as well, causing the British to be caught in crossfire. In addition, a fresh regiment of patriots approached from behind. Thirty British people were killed or wounded in this firefight, while the Americans lost four men. The British were able to escape from the ambush at a run on the street, as the Americans could not keep up with this speed in the swampy and overgrown terrain to the sides. The American troops that followed on the road were too poorly organized and too close together to attack.

At this point there were already about 2,000 Americans in the area. Smith sent out scouting patrols again. When three companies of militiamen attacked the head of Smith's entourage at Hartwell's farm, the scouts fell in the back and surrounded them. Scouts also succeeded in stabbing the Lincoln militia in the back with a successful surprise attack on the boundary between Lexington and Lincoln. But the British lost more and more men in these skirmishes and through constant fire from a great distance beyond their own range.

In the borough of Lexington, Captain John Parker had gathered the Lexington militia on a hill. Some of them were already bandaged from earlier meetings of the day. These men did not snap their trap shut until Lieutenant Colonel Smith himself appeared in view. He was hit in the thigh and the entire British entourage came to a halt. From then on, this ambush was called Parker's Revenge. Major Pitcairn sent infantrymen up the hill to push Parker's men back.

The Royal Marines cleared two more hills called The Bluff and Fiske Hill, but suffered casualties in militia attacks. In the attack on Fiske Hill, Pitcairn fell from his horse and injured his arm. Now the two leaders of the expedition to Concord were wounded. Their men were tired, thirsty, and their ammunition was running out. Some surrendered. Most gave up and fled. One hill, Concord Hill, lay before the center of Lexington. Some uninjured officers turned to their soldiers and threatened them with bayonets if they did not regroup. The Americans had attacked in large closed formations at least eight times on the way from Concord to Lexington. This contradicts the political myth that the Americans mainly attacked in secret behind walls and fences. Although, of course, such attacks also happened and became the preferred tactic later in the day.

Only one British officer of the three companies at the helm was unharmed that day. He was already thinking of giving up when he heard his men at the top shout enthusiastically. A whole British brigade with artillery and about 1,000 men came for reinforcements, led by Brigadier General Lord Hugh Percy. It was now 2:30 p.m.

Percy's rescue

General Gage had given orders that reserve troops should gather in Boston at 4:00 a.m. But since he was anxious to keep the operations secret, he had written only one letter to a general whose servants left him on a table. At about 5:00 a.m. Smith's request for reinforcements reached Boston, and orders were now being sent to three infantry regiments (4th, 23rd, and 47th) and a battalion of Royal Marines to rally. Unfortunately, again only a copy of the letter was sent to each commanding officer, and the letter to the Marines was addressed to Major Pitcairn, who was already in the Lexington field. After these delays, Percy's brigade left Boston at 8:45 a.m. His troops went out with the song Yankee Doodle to have some fun with the townspeople. Less than two months later, at the Battle of Bunker Hill , this song was to become very popular among American soldiers.

Percy took the overland route over the Boston Neck and over the Great Bridge. He ran into a deeply lost Harvard professor and asked which road would lead to Lexington. The Harvard man showed him the right way without thinking. As a result, he later had to go into exile under pressure from residents because he had supported the enemy. Percy's troops arrived in Lexington at around 2:00 p.m. In the distance they heard rifle shots as they set up their cannons and the regulars' formations in higher ground with an overview. Lieutenant Colonel Smith's men were approaching in frantic flight, followed by a regiment of New Englanders in orderly formation. Percy ordered his artillery to open fire at long range. The New Englanders then dispersed. Smith's men collapsed from exhaustion once they were safe.

Against the advice of the Quartermaster General, Percy had left Boston with no extra ammunition for his men or the two artillery pieces. He thought more cars would unnecessarily delay the march. After Percy left town, Gage sent two ammunition wagons behind them, guarded by an officer and 13 men. This ammunition train was intercepted by a small detachment of patriots who were on the notification list but couldn't join the militia because they were over 60. These men rose from their ambush and demanded that the soldiers surrender and give them the ammunition wagons. But the regulars ignored them and pushed their horses on. The old men then fired, killed the horses at the head of the teams and the two NCOs and wounded the officer. The survivors ran for their lives, six of them throwing their guns into a pond before meeting a poor old woman named Mother Batherick digging greens in a field for food. They surrendered to this and took them to the house of the local militia captain. Each man in Percy's brigade only got 36 rounds, and the artillery pieces only got a few rounds in the limbs .

Lexington to Menotomy

Percy brought order back to the combined troops, now about 1900 men, and let them rest, eat, drink and treat the wounds at the field headquarters in Monroe's tavern. They moved out of Lexington around 3:30 p.m.

Brigadier General William Heath took command of the Massachusetts Militia in Lexington. Earlier that day he had first traveled to Watertown to discuss how to proceed with Joseph Warren and other members of the security committee. Heath and Warren, in response to Percy's artillery and British patrols, ordered the militias to disband the closed formations. The formations would only attract unnecessary artillery fire. Instead, they surrounded Percy's marching formation with a mobile ring of skirmishers who were supposed to inflict the greatest possible number of losses on the enemy from a distance. This should minimize the risk for the individual militiamen involved.

Mounted militiamen dismounted on the street, shot at the approaching regulars, mounted again and galloped away. Then the whole thing was repeated from the beginning. Militiamen on foot positioned themselves in front of sloping terrain and fired from a distance. The typical hunting weapon used by American farmers was far better suited for long-range shots than the British musket. Wounded British rides with the cannon and had to dismount when piles of militiamen were shot at. Often times, Percy's men were surrounded by Americans. But they had the advantage of the shorter distances. Percy could send his troops to where they were needed more quickly, while the Americans had to bypass the British formation in a wide arc.

Percy wrote of the tactics used by the Americans: “... the rebels attacked us in very dispersed, unusual ways, but with perseverance and determination; nor did they dare to line up in a proper formation. In fact, they knew all too well what to do. Whoever sees them as a messy bunch is making a big mistake. "

Heath succeeded in creating a moving circle of intentionally dispersed forces. To do this, he sent company officers into the field and sent orders to the approaching distant units. Warren and Heath also often led the skirmishers personally into battle. This point of the struggle is often wrongly described as if the Americans no longer had a clear command structure.

The struggle intensified as Percy's forces from Lexington invaded Menotomy. New militias fired at the British lines from a distance, and individual residents fired at the British from their property. Some houses were used as hiding places for snipers. Jason Russell urged his friends to defend his house with him, saying: "An Englishman's house is his castle" (cf. "a man's home is his castle" ). He stayed and was killed on his threshold. His friends escaped into the basement by shooting the soldiers who were coming down the stairs. The bullet holes can still be seen in the house. A militia unit attempting an attack from Russell's orchard was caught by scouts. Eleven men lost their lives, some after surrendering.

Percy lost control of his men and British soldiers committed atrocities to avenge themselves for scalping their comrade on the Old North Bridge and the losses inflicted on them by the distant, often unseen Americans. Houses were looted and set on fire, and everyone in them was killed. Two innocent drunkards were executed in a tavern. Many of the regulars got drunk too. The silver objects of the mass were stolen from a church. But they were recovered when they were sold in Boston. Resident Samuel Whittemore killed three regulars before being attacked by a British detachment and left dying. All in all, more blood was spilled at Menotomy than anywhere else that day. The Americans had 25 dead and nine wounded, the British 40 dead and 80 wounded. That was about half of those killed that day for each side.

From Menotomy to Charlestown

The British troops crossed the boundary to Charlestown as the battle intensified. New militias kept arriving in formation, and Percy positioned his cannons and scouts against them at the intersection called Watson's Corner. With that he could inflict heavy losses on them.

Earlier that day the American General Heath had ordered the Great Bridge to be torn down. Percy's brigade was now approaching the broken bridge, with the river bank full of militiamen. He escaped this impasse by following a narrow path sideways and continuing across the street to Charlestown. The now about 4,000 militiamen had not expected this sudden swing, and the orbit dissolved. Several Americans occupied Prospect Hill above the road, but Percy positioned his cannons and drove them away with the last few shots.

A large group of militias arrived from Salem and Marblehead . It might have cut off Percy's path, but it stopped on nearby Winter Hill, allowing the British to escape. Some later accused their leader of deliberately letting the royal troops pass in order to avert a real war over the total defeat of the British. The commander defended himself by referring to alleged orders from Heath, which he denied. At dusk, Pitcairn's Royal Marines threw back one final attack on the rearguard of Percy, who had just reached Charlestown. The regulars related to hill defensive positions. Some of them had been without sleep for two days and had marched 40 miles in 21 hours, including eight hours of fighting. But now they had an advantage on the hills at sunrise and were supported by heavy cannons from HMS Somerset. Heath studied the position of the British Army and decided to withdraw the militia to Cambridge.

consequences

The morning after, Governor Thomas Gage woke up to find that Boston was being besieged by a very large militia army ( Siege of Boston ) that had marched in from all over New England. In contrast to the Powder Alarm, blood had really been shed before this time. The American Revolution had begun. The militia army continued to grow as men and supplies were brought into Boston from the surrounding colonies. The Continental Congress began to shape these men into the forerunner of the Continental Army . Even now, after the first open fighting, Gage refused to enforce martial law in Boston. He convinced the city's elected officials to hand over all weapons to him in private hands. In return, he promised that any resident would be allowed to leave the city if they wished.

In terms of the eventual outcome of the Revolutionary War and the actual losses suffered, the battles at Lexington and Concord were not a major battle. It was a significant failure for the British political and military strategy to regain control of the Massachusetts province through the Intolerable Acts and the seizure of military equipment. The Lexington and Concord expedition provoked just the kind of skirmishes with the militia that it was supposed to prevent. In addition, only a few weapons could be confiscated.

The military skirmishes were followed by a struggle for political opinion in motherland Great Britain. Within four days of the skirmish, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress had compiled a multitude of sworn eyewitness accounts from militiamen involved and captured British soldiers. After it was leaked a week later that Gage was sending his official account of the events to London, the Provincial Congress sent over 100 of his collected eyewitness accounts on a faster ship there. They were turned over to an official who was benevolent of the American cause and soon appeared in the London press. It wasn't until two weeks later that the ship arrived with Gage's report, the details of which were so vague that he could barely influence public opinion. Even George Germaine , who was a critic of the colonists, wrote of the report: "... the Bostonians have the right to call the royal soldiers 'aggressors' and claim a victory for themselves." Politicians in London made in the Afterwards, Gage was responsible for the conflict instead of looking for the causes in her own policies and instructions.

The British soldiers in Boston also frequently blamed Gage for the events in Lexington and Concord. Two weeks later, the Battle of Bunker Hill occurred at the same place where the Regulars found refuge after the fighting . Both Dr. Joseph Warren and Major John Pitcairn were killed in this battle. With Warren also died whoever knew the name of the informant about the planned expedition to Concord.

After the fighting, the prevailing opinion on American soil was that no one of rank could now stay out of the conflict. The following day, John Adams visited the battlefields. This convinced him that "... the die had now been cast, the Rubicon was crossed." Thomas Paine in Philadelphia had viewed the conflict between the colonies and the motherland as a kind of legal process, but after hearing news of the fighting, "refused who abandoned the unyielding, sullen Pharaoh of England for good. ” George Washington , himself a slave owner, received the news on his property on Mount Vernon and wrote to a friend:“ ... the once happy and peaceful plains of America will either become in blood to be watered or inhabited by slaves. What a sad alternative! But can a virtuous man hesitate in this choice? ”A group of hunters in the borderland to the largely unexplored areas inland named their camp site Lexington when they heard of the fighting in June. From this grew the city of Lexington , Kentucky. In 2000, eight times as many people lived there as in the Massachusetts town of the same name.

Historical representation of the events

The early American governments made it a point to portray British actions as wrong and American actions as an innocent response. Aspects such as the patriots' preparations, their intelligence work, warning signs and doubts about who fired the first shot were rarely discussed. Written articles describing such activities have not been published but have been returned to the authors. Paintings depicted the battles in Lexington as an unjustified massacre.

During the nineteenth century the question of which side was to blame for the dispute became less important. Instead, in the minds of many Americans, the events took on a downright mythical quality. Now there was a complete re-evaluation of the events. The patriots were portrayed as aggressively fighting for their cause, no longer merely as innocent victims of acts of the British forced upon them. Paintings of the fighting in Lexington from this period show the militia standing upright and fighting back defiantly.

In 1837 Ralph Waldo Emerson immortalized the events at the Old North Bridge in his Concord hymn :

| By the rude bridge that arched the flood, Their flag to April's breeze unfurled; Here once the embattled farmers stood; And fired the shot heard around the world. |

On the rough bridge that spanned the floods , they unfolded their flag in the April wind; The armed peasants once stood here; and fired the shot that was heard around the world. |

After 1860, several generations of school children learned Longfellow's poem Paul Revere's Ride by heart.

Anglophilia in the United States around 1900 resulted in more balanced interpretations of the history of the fighting. During the First World War , a film about Paul Revere's ride was confiscated under the Espionage Act of 1917 . This was justified by the fact that the film sowed discord between the United States and Great Britain.

The tactics and strategies used by the British Army at Lexington and Concord have often been aptly compared to those used by the United States Army in the Vietnam War . During the Cold War , conservative politicians tried to co-opt the Minutemen as symbols of entrepreneurial freedom, while their liberal opponents portrayed them as anti-imperialist freedom fighters. Today the events surrounding the skirmishes are often used or misused in connection with the dispute over gun control and the Second Amendment , depending on political views.

The US writer Esther Forbes has also dealt with the battles of Lexington and Concord in award-winning books, for example in her novel Johnny Tremain. A Novel for Old and Young ( Johnny Tremain. A Novel for Old and Young , 1944). This was created in 1957 by Robert Stevenson with Hal Stalmaster , Luana Patten , Jeff York , Sebastian Cabot and others. a. Filmed for Walt Disney .

In 1961, novelist Howard published Fast April Morning , a portrayal of the fighting from the perspective of a fictional 15-year-old. In the years that followed, this representation was often used in secondary education. In 1988 this portrayal was made into a film with Chad Lowe and Tommy Lee Jones .

Massachusetts, Maine and Wisconsin celebrate Patriots' Day in honor of the fighting.

literature

- David Hackett Fischer: Paul Revere's Ride , ISBN 0-19-508847-6 .

Web links

- At Lexington and Concord and 19 April Why do we remember (English)

- Description of the battle with photographs of the locations and buildings ( Memento from September 30, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- Battles of Lexington and Concord (English)

- Reports on the Concord battles in Concord Magazin ( Memento from August 10, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- Midi file of "The White Cockade", the song that was intoned by the Minutemen in Concord by the Old North Bridge

References and comments

- ↑ Lerg, Charlotte A. The American Revolution . A. Francke Verlag (UTB Profile), Tübingen 2010. ISBN 978-3-8252-3405-8 , p. 39, line 2.

- ↑ Lerg, Charlotte A. The American Revolution , p. 37.

- ↑ cf. Lerg, Charlotte A. The American Revolution , p. 39: "It was a small force, no more than 60 men".

Coordinates: 42 ° 26 '58.7 " N , 71 ° 13' 51" W.