Battle of Preston (1648)

| date | August 17th bis 19th August 1648 |

|---|---|

| place | Preston , north of Warrington , Lancashire , England |

| output | decisive victory of the parliamentary troops |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 18,000 soldiers | 14,000 soldiers |

| losses | |

|

4,000 dead, |

low |

Wars of the Three Kingdoms (1639–1651) in Scotland

Newburn - Marston Moor - Tippermuir - Aberdeen (1644) - Inverlochy (1645) - Lagganmore - Auldearn - Carlisle (1645) - Alford - Kilsyth - Philiphaugh - Aberdeen (1646) - Rhunahaorine Moss - Dunaverty - Mauchline Muir - Preston (1648) - Whiggamore Raid - Stirling (1648) - Inverness (1649) - Inverness (1650) - Carbisdale - Dunbar (1650) - Inverkeithing - Worcester - Tullich

The Battle of Preston (August 17 to August 19, 1648) ended with a victory for Oliver Cromwell's troops over the royalists and the Scots led by the Duke of Hamilton . The victory of the parliamentarians heralded the end of the Second English Civil War .

prehistory

After the Scottish army handed Charles I of England over to the plenipotentiary of Parliament in Newcastle in January 1647 , concern grew in Scottish circles about the increasing radicalization of politics in England. It was also about the fate of the king, especially after he was kidnapped in June by George Joyce from the custody of the MPs and was now under the control of the New Model Army .

In London, Presbyterians found themselves increasingly troubled in Parliament, while the influence of the Independents grew. Various groups radicalized, partly in the religious field, partly - like the Levellers and smaller groups - in the political. In comparison, the radical Presbyterian Party of Scotland became increasingly a moderate faction, led by James, Duke of Hamilton.

The first and foremost duty of the Government of Scotland had to be to keep the King safe. Measures to do this, however, could only be justified if the king again accommodated the Scottish Covenanters . So it had to be negotiated with him first, taking into account both more moderate positions and those of the more radical Presbyterians. The latter were led by the Marquess of Argyll , the supporters are also known as the Kirk party.

The months of negotiations finally culminated in an agreement between Charles I and the Scottish representatives in December 1647 at Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight . In it the king agreed - without taking the side of the Covenanters - to promote and uphold Presbyterianism in England on a trial basis for three years; all other sects, including the independents, should be suppressed. In return, he was promised an army. This agreement, called Engagement , led to the Second English Civil War and split the Covenanter movement.

Preparations

In Scotland, the news of this agreement was greeted with enthusiasm at first, as it was assumed that Charles I had finally sided with the Covenanters. When this proved to be in error, strong opposition to the king's support quickly arose, especially in southwest Scotland, where the Covenanters were strongest.

Worse than the political opposition, however, was the widespread resistance that arose right down to the parishes; it seriously hampered efforts to raise an army.

In April, Hamilton was appointed commander; however, his military capabilities still undercut his poor political ones. Patrick Gordon of Ruthven says of his appointment:

“But, oh sorrow! this is where our misery began. The Divine Majesty was not satisfied with us; we should have been more humble; and therefore God tolerated their erroneous assumption of choosing the greatest man in the kingdom, that they thought he was the wisest man, the most astute man, the greatest statesman, and the most profound politician, not just of the three kingdoms but of all Christianity: which just had the shortcoming that he had never practiced the art of war before. He would have been more suitable as a councilor than as a council of war; he could have chaired the most solemn Senate in the Vatican, but he didn't know how to lead an army. "

Throughout the spring and early summer soldiers were raised with great difficulty. This time delay had a fatal effect on the outcome of the entire company, as it meant that the New Model Army was able to stifle the royalist uprisings that had already broken out in England and Wales. In addition, Hamilton had to put down a rebellion in Scotland itself, in the western counties. He succeeded in doing so in June at the Battle of Mauchline Muir , but at the cost of a division of his military forces.

Time passed and midsummer was already over. Many of the royalist uprisings in England had already been put down. The conditions were poor - the army was far from having the power to strike, poorly equipped and insufficiently trained, the problems of supply and transport were unsolved, and there was a lack of artillery. The expected reinforcement by the Scottish Army in Ireland had not materialized either. Nevertheless, Hamilton could not risk a further delay, so he crossed the English border at Annan on July 8th with 10,500 men instead of the originally planned 30,000. On the same day he united in Carlisle with a royalist force of about 3,000 English cavaliers. The advance of this army was closely watched by General John Lambert and a branch of the New Model Army.

March from Hamilton

Hamilton's advance south was painfully slow. Not understanding or neglecting the need for quick action, he spent six days in Carlisle before the army marched on Penrith , wasted another three days there, then covered the few miles to Kirkby Thorne , where it remained until the end of July. The horrific weather made things worse, as it rained the entire time Hamilton was in England. The stay at Kirkby Thorne was described by Sir James Turner:

“The Duke found it necessary to spend ten or twelve days in Kirkbie-thorne to send back the regiments marched from Scotland, which were less than half their strength and were made up of rude and undisciplined newcomers: and this summer was extreme rainy and wet that I would say that during the whole time in England it was impossible for us to handle one out of ten muskettes. "

Lambert constantly watched the situation, ready to respond to any enemy movement. Not strong enough to venture into a confrontation himself, he received news that Oliver Cromwell had wrested Pembroke Castle from the Royalists on his way from South Wales on July 11th .

At the end of July, the Scots' clumsy war machine let itself be carried away into action. She moved to Kendal via Appleby and arrived there on August 2nd. Here her General George Munro of Newmore and his troops from Ulster joined. The combined force now had the strength of just over 18,000 men, on horseback and on foot. But immediately a serious argument broke out. Munro refused to serve under Hamilton's second in command, the Earl of Callendar , whom he deeply disliked. And Callendar, for his part, saw no reason why Munro should be given an independent command of command. Hamilton, who apparently feared Callendar, chose the worst of all solutions. The slaughtering troops from Ulster were left behind at Kirkby Lonsdale with some English cavalry to await the artillery which was already on its way from Scotland while the rest of the army continued their march to Hornby . This is where Hamilton settled for a week - the first in a series of disastrous decisions.

On August 14, the listless trek headed for Lancaster and then Preston . Sir Marmaduke Langdale and the remaining English cavaliers were posted some distance from the main eastern army to protect the flank and to attack if enemy movements were found in the Pennines area .

While Hamilton was paralyzed by Lancashire , Cromwell had made remarkable progress since leaving Pembroke . On August 13, he came across Lambert between Wetherby and Knaresborough and had covered 462 km in thirteen days. In contrast, when Hamilton reached Preston two days later, it had taken 39 days to travel 151 km. Cromwell's forces were now 14,000 strong, weaker than their opponent, but stronger than Cromwell later reported. With Sir Thomas Fairfax and the rest of the New Model Army, he had finished off the royalists in south-east England in passing. This was the first time that Cromwell was an independent commander in chief.

Hamilton did not yet suspect the danger that cast its first shadow on his eastern flank. Due to persistent supply and lodging problems, he allowed John, the future Earl of Middleton , and the cavalry to ride further south of Preston , to cross the River Ribble and to make an advance to Wigan to requisition food. On August 16, the eve of the Battle of Preston, the Engager Army was shaped like a serpent stretching an incredible 15 miles: Munro and the rest were still in Kirkby Lonsdale to the north. Hamilton and the main army were close to Preston. Meanwhile, Middleton and the beginning of the line were in Wigan to the south. Langdale and his separate armed forces of English royalists had ridden south of Settle via Ribblesdale at the time and were reaching Preston from the northeast.

The Cromwell attack

Cromwell had no precise information about Hamilton's whereabouts at Wetherby . The usual tactic would have been to go back south to cover the route to London while scouts of cavalrymen were sent west to track down the enemy. But Cromwell, seeing the need for a quick decision, put it all on a brilliant plan. Instead of moving south, he decided to cross the Pennines in Lancashire to start a search and destruction campaign. Coming from Otley to Skipton he climbed into the Ribble Valley and camped on August 15th in Gisburn . Here Cromwell received the message from his scouts that Hamilton was approaching Preston from Lancaster.

Langdale realized the danger far too late. He informed Hamilton and Callendar that he believed Cromwell was about to attack. Neither of them took the news seriously. In the early morning of August 17th, his fears were confirmed. His men still held a good position astride the main road between Preston and Skipton , which was little more than a channel now saturated with rainwater. On the other hand they were protected by hedges that enclosed a small field that also protected them from a cavalry attack. Cromwell sent another force of 200 cavalrymen and 400 foot soldiers to force passage through the fairway. Soon after, they were reinforced by Captain John Hodgson, whose memoir recorded the opening scenes of the Battle of Preston:

“And at Longridge Chapel our horses met Sir Marmaduke in a very favorable line-up ... And here by the side of a bog we positioned ourselves (it was only a small bunch of us, no more than half as many we should have been), the general came to us and gave us the marching orders. We didn't even have half of the men together, hoping for a respite, so he said: 'March!' "

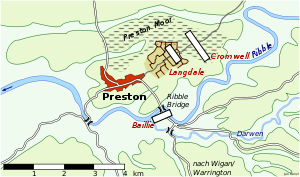

Step by step the royalists were pushed back, they gave way over the rain-soaked ground. While the battle was in progress, Langdale rode away to warn Hamilton that he was not being attacked by a vanguard, but that he was facing a regular, full attack. Langdale met Hamilton with General William Baillie as they were preparing to have the infantry cross the River Ribble over the Preston Bridge. Hamilton revoked all his previous orders, told Baillie to stay on the north side to strengthen Langdale, and sent a message to Middleton to rush over from Wigan . But Callendar objected that without immediate cavalry support, the infantry would soon be destroyed. Once united with the cavalry, he went on, the army would have the advantage that the River Ribble would be ahead, not behind. No consideration was given that this would cut it off completely from Munro and Scotland. Langdale, however - so Callendar - exaggerated the strength of the enemy attack excessively, if necessary he could find his way back to Preston to join the bulkheads south of the Ribble Bridge. Hamilton was convinced and rejected his original plan. The only aid sent to the hard-pressed forces of Langdale was a small force of Lancers. One mistake followed another.

The battle of Langdale between the hedgerows and ditches of the Ribbleton Moors was already in its fourth hour. In order to finally drive the enemy infantry out of the hedges, Cromwell sent two cavalry regiments down the fairway, which chased the panicked royalists in the direction of the city. Langdale managed to join Baillie, but most of his infantry who survived the fight were captured while his cavalry galloped north to join Munro. Hamilton himself came to Langdale's aid with his life guards. However, his personal courage in battle by no means made up for his lack of skills as a general.

South of the river, Baillie posted his men by Brow Hill Church , overlooking the Ribble Bridge. Cromwell's men approached the vital crossing from the high bank to the north and were covered by musketeers. The battle for the Ribble Bridge lasted two hours, a very heated argument , to put it in Cromwell's own words. As evening fell, the Scots were threatened by the attack of the pikemen under Captain Thomas Pride and Richard Dean. As Baillie drew back, the battle flared up over the bridge over the Darwen, a small tributary of the Ribbles, which later induced the poet John Milton to write, imbued with Darwen's stream, with the blood of the Scots . The fierce fighting only ended in the night.

Further course of the battle

The darkness was a welcome break for both armies, whose soldiers were sweaty, tired and hungry. But an optimistic attitude prevailed among the parliamentary troops, they already felt themselves to be future winners. The Cromwell flank attack had been a resounding success: Hamilton's army was divided, cut off from supplies from Scotland, and had no means of retreat. By the end of the first day of the fight, the Engagers had lost (according to Cromwell, 1,000 of them had died and 4,000 had been captured); her army was still powerful, but it soon lost all confidence in the abilities of its commanders.

There was no break for the worn-out Scottish soldiers. At midnight it poured down and Hamilton was holding a council of war, and the mood was morose. Callendar urged a night march to meet Middleton and the cavalry coming from the south. Baillie and Turner both argued against it, pointing out the difficulty of leading a tired army down a dirty street on a dark, wet night, but, as is so often the case, Callendar prevailed. Because the army had no means of transport, the musketeers were only allowed to take gunpowder with them , as much as they were able to carry. Like Callendar's other plans, this was pretty half-baked. No order was given to set fire to the remaining powder, so that it could be captured by Cromwell's soldiers the following morning. The worn-out soldiers strode into the night with no drums and no lights.

Everything went wrong on this march that could go wrong. While Middleton rode north of Wigan via Chorley , Hamilton marched south through Standish, in such a way that the two forces marched past each other that night. The first to notice this was Middleton when he came across two regiments of the Ironsides under Colonel Francis Thornhaugh, whom Cromwell had sent out to pursue Hamilton, not - as expected - his infantry . In the battle that followed, Thornhaugh was killed, but his men drove Middleton almost all the way back south.

Hamilton was three miles from Preston when Cromwell noticed his disappearance. After sending Thornhaugh to pursue Hamilton, Cromwell followed with the rest of the army. He left Colonel Ralph Ashton and the Lancashire recruits to defend Preston in case Munro attacked. Cromwell ordered all of Langdale's captured soldiers to be killed in this case. Ashton didn't need to worry: Munro made no move to leave Kirkby Lonsdale.

The rain poured heavily during the night and during the day. The Scottish infantry were soaked and half starved by the morning of August 18th. At Standish Moor near Wigan they finally rejoined the cavalry. This was a good place to build a position because the ground was fenced. Unfortunately, the rain rendered the last available powder unusable and, when there was nothing left, the tiresome march continued to Wigan, where the poor inhabitants were literally looted mostly to the skin by desperate soldiers who were now on the fringes the panic were. The army was close to disbanding.

From Wigan the retreating army plowed its way through the morass towards Warrington , closely followed by Cromwell. On the morning of August 19th the Scots faced their opponents in a square near Winwick . Cromwell later described the fight like this:

“We held them in check until our army appeared, they withstood the advance with great determination for several hours: ours and theirs began to advance with pikes and attack very closely, forcing us to clear the ground; but our men quickly recaptured it with God's blessing and attacked them very hard, knocking them from their place, where we killed more than a thousand and (we believe) took more than two thousand prisoners "

The fight now shifted to a nearby lane on the road north of Newton-le-Willows . All of Cromwell's attacks were repulsed until the locals showed him a way through the fields to bypass the Scots' position. The Scots were then repulsed by the High Pride Regiment to the village meadow south of Winwick's Church , where the resistance finally broke. The fugitives made their way towards Warrington , where the rest of the army was busy barricading the road across the River Mersey .

Even after the Winwick victory it might have been difficult for Cromwell to follow the Scots south, across the Mersey, where they had built a strong beachhead. But although Hamilton still had most of the horses and 4,000 infantry, his army was already defeated. Callendar, who now held his hand, persuaded him to instruct Baillie to surrender with the now useless infantry while the cavalry was still trying to join the fighting royalist forces in Wales . Baillie, who according to his fellow officers was shocked by the order, refused to obey. Instead, he gave the order to defend the bridge, an honorable but utterly unrealistic decision. Most of the musketeers threw away their useless weapons. Those who kept them had neither lead nor powder, and the pikemen were on the verge of collapsing. When the order was given, only 250 men followed. Baillie gave up in time; Cromwell, anxious to take the bridge at Warrington, granted his duty on generous terms. By the end of the battle, from Preston to Warrington, 3,000 men of the royalist troops had been killed and 10,000 captured.

surrender

Without orientation, Hamilton and his cavalry landed on August 22nd at Uttoxeter in Staffordshire . Here he finally found the opportunity to blame Callendar for the whole debacle. Turner, who was an eyewitness to the dispute, wrote:

“The Duke and Callendar were abusive and extremely irritable at dinner, which I was present at: each accused the other of the misfortune and failure of our fight, and I think the Duke had the better cards. And here I want to mention that it was My Lord Duke's big mistake in giving E. Callendar too much of his power: I often heard him grant what he was asked to do and promise to be very pleased with it . And that's why Calendar was doubly guilty, first of all because of his bad behavior (which was inexcusable), and also of accusing the Duke of something he was guilty of himself. "

This is still generously judged: if Callendar's behavior was bad, Hamilton's was disastrous, a complete failure. The ability to compromise may be necessary for a politician, but it is seldom useful for a military commander. Unable to lead the resistance in Scotland, unable to give his troops clear tasks, Hamilton's engagement led to a disaster. He wasn't a traitor, as Montrose said, but he was simply the wrong man in these times.

When they were ordered to continue their senseless ride from Uttoxeter, the cavalry mutinied. Many deserted, including Langdale. Others eventually rode away with Callendar, who managed to escape to the Netherlands . Hamilton had no choice: after his security and that of his officers had been guaranteed, he surrendered to John Lambert, whom Cromwell had entrusted with his pursuit. The word was not kept. Under his English title, that of Earl of Cambridge, Hamilton was tried and executed for treason in March 1649, just weeks after his royal employer, whom he served and for whom he lost.

News of the Lancashire defeat caused the engagement movement in Scotland to collapse. From the southwest of Scotland, Argyll supporters and the Kirk Party marched on Edinburgh , an event known as the Whiggamore Raid (the word whiggam used to drive the horses). With that, the Whigs entered history.

literature

Primary literature

- Gilbert Burnet: Memoirs of the Lifes and Actions of James and William, dukes of Hamilton. 1852.

- WC Abbot (Ed.): Oliver Cromwell. Writings and Speeches. 1937-47.

- John Hodgson: Memoirs. 1806.

- Patrick Gordon of Ruthven: A Short Abridgement of Britane's Distemper. 1844.

- Sir James Turner: Memoirs of his own Life and Times, 1632-1670. 1829.

Secondary literature

- TS Baldock: Cromwell as a Soldier. 1899.

- E. Broxap: The Great Civil War in Lancashire, 1642-1651. 1913.

- F. Hoenig: The Battle of Preston. In: Journal of the Royal United Services Institute , Volume 52, 1898.

- RA Irwin: Cromwell in Lancashire: the Campaign of Preston 1648. In: The Army Quarterly , vol. 27, 1933-4.

- HL Rubinstein: Captain Luckless. James, First Duke of Hamilton, 1606-1649. 1975.

Web links

- 1648: The second English Civil War (English)

- The Battle of Winwick Pass on August 19, 1648 (English)

Coordinates: 53 ° 45 ′ 10 " N , 2 ° 40 ′ 46" W.