Sundial (Ancient Egypt)

The ancient Egyptian sundial (also shadow clock ) was used to measure the seasonal hours of the day , which in the later course of Egyptian history were coordinated with the ancient Egyptian water clock . The fluctuation range of the seasonal time units measured in this way was between six and 18 hours of the day.

history

Ideally, the use of sundials allowed the Egyptian day to be subdivided into twelve hours , which probably emerged as a result of the division of the night into twelve dean hours , because in the Old and Middle Kingdom only the hours of the night were mentioned in more detail. Earlier texts only refer to general information on the measured hours of the day. From the reign of Thutmose III. (1479 to 1425 BC) the discovery of a five-caliber sundial, which at noon, when the sun was at its zenith , was rotated 180 ° to the west after previously facing east . This technology made it possible to display twelve hours of the day. The periods before sunrise and after sunset were not measurable with this sundial, but this was also not necessary with regard to the division of the day, since the ancient Egyptian day began with sunrise and ended with sunset. The use of sundials of this type is known, for example, from the texts about the battle of Megiddo . Thutmose III. mentioned on the 19th Schemu I 1457 BC On arrival at Qen the seventh hour of the day.

The development of the Egyptian hour division can most likely be seen as a forerunner for the two twelve temporal hours of the Greeks and Romans , which in turn form the basis for the division of the planetary gods for one hour each in the planetary day-week . Herodotus , however, denied an Egyptian influence on the division of the Greek day into twelve parts (mèrea), which were determined with the help of a sundial with a gnomon . His descriptions of the twelve-hour day model with reference to its origins in Babylonia appear questionable, however, since Ludwig Borchardt also referred in this context to the Babylonian division of hours, which in its sexagesimal system only knew a corresponding six-division of the day or night.

Sundials in ancient Egypt

A scale generally used for each season led to slightly different values over the course of the year due to different day lengths. The Egyptians did not aim to introduce equinoxes , which allow 24 units of equal length within a day, regardless of the season, although they had the necessary knowledge. They deliberately avoided this option because the use of equinox hours was not compatible with the existing mythology . This fact can be seen in the scales of the sundials, which in principle function correctly, but which are based on the traditional religious division of hours .

In this context belong the earliest textual evidence that includes curriculum instructions on how to measure hours of the day. The explanations there were intended for the construction of a sundial in the Osireion , which probably date from the time of Seti I (1290 to 1279 BC). According to a “regulation for determining hours”, the first two hours of the morning were not measured at all. The “hour of noon” ( ahat ) counted as free time in agriculture .

Such a sundial has a three-part scale with which four hours of the first half of the day can be measured, whereby this sundial was oriented to the east "towards the sun god Re " in the first half of the day . The times of twilight could then be counted mythologically as the ancient Egyptian day; in the deans' hour schedules, however, they belonged to the night. It remains unclear whether this type of sundial was also used for the second half of the day.

Shapes of the sundials in ancient Egypt

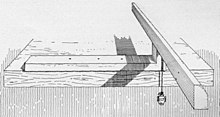

Shadow clock

The shadow clock consists of a longitudinal bar on which the respective hour periods are marked, and a cross bar (presumption: a holy cubit) as a shadow thrower, which is probably placed at the end of the longitudinal bar. The longitudinal beam was placed on the floor in an east-west direction. In the morning its free end pointed to the west. At noon the clock was turned (free end of the longitudinal bar to the east) and the position of the sun in the second half of the day was displayed with the same device . Because the shadow object was positioned horizontally and not parallel to the earth's axis, it was not possible to use them to display the time independently of the season and even over the day (see wall sundial, below).

Side light sundial

The oldest known grazing light sundial with an inclined collecting surface dates from the Ptolemaic period. Opposite the collecting area there is a square attachment as a shadow projector. A plumb bob can be attached to the side to set the clock horizontally. The sundial is to be turned in such a way that the shadow-casting edge is perpendicular to the solar azimuth . The collecting area is provided with seven six-part scales on which the seasonal daily hours for each month can be read. Fragment of a sundial sundial (part with collecting surface), see :. This clock belongs to the altitude sundials . It is the only known sundial from ancient Egypt that correctly displayed each season of the year.

Wall sundial

A sundial that can be hung on a wall with a cord dates from the 13th century BC. BC ( New Kingdom ). Their vertical collecting surface is semicircular. The reading scale for twelve hours consists of 13 radial lines scratched in stone, in the center of which there is a hole for a horizontal, shadow-casting bronze pen. The lines have the same angular distance from one another. The modern name of such a clock is canonical sundial (mainly used in monasteries in Europe during the Middle Ages). They cannot be used to display the time that is independent of the season and that is uniform over the day.

Exhibitions

Ancient Egyptian sundials can be seen in the following locations:

- Berlin : Egyptian Museum (all types)

- Brussels : Royal Museums of Art and History (sundials with vertical and inclined collecting surface)

- Cairo : Egyptian Museum (all types)

- London : University College ( Petrie Museum ) (sundials with inclined collecting surface)

- New York : Metropolitan Museum of Art (all types)

- Paris : Collection Hofmann (sundials with inclined collecting surface)

- Turin : Museo delle antichità egizie di Torino (sundials with inclined collecting surface)

- Rome-Vatican : Gregoriano Egizio (all types)

See also

literature

- Richard Anthony Parker : Egyptian Astronomy, Astrology and calendrical reckoning. In: Charles-Coulson Gillispie: Dictionary of scientific Biography. American Council of Learned Societies. Vol. 15, Supplement 1 (= Roger Adams, Ludwik Zejszner: Topical essays. ) Scribner, New York 1978, ISBN 0-684-14779-3 , pp. 706-727.

- Ludwig Borchardt : Ancient Egyptian timekeeping. In: Ernst von Bassermann-Jordan (ed.): The history of time measurement and clocks. Volume I, delivery B, De Gruyter, Leipzig / Berlin 1920.

- Siegfried Schott : Ancient Egyptian festival dates. Publishing house of the Academy of Sciences and Literature, Mainz / Wiesbaden 1950.

- Alexandra von Lieven : The sky over Esna. A case study of religious astronomy in Egypt using the example of the cosmological ceiling and architrave inscriptions in the Temple of Esna. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2000, ISBN 3-447-04324-5 .

- Alexandra von Lieven: Floor plan of the course of the stars. The so-called groove book. The Carsten Niebuhr Institute of Ancient Eastern Studies (among others), Copenhagen 2007, ISBN 978-87-635-0406-5 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Inventory number of the Egyptian Museum Cairo : 33401.

- ↑ The name of the shadow clock comes from Richard-Anthony Parker , Ludwig Borchardt described this type of clock as a sundial with a horizontal collecting surface .

- ^ A b c Richard-Anthony Parker: Egyptian Astronomy, Astrology and calendrical reckoning. New York 1978, pp. 713-714.

- ^ Kurt Galling: Text book on the history of Israel. (TGI). Mohr, Tübingen 1979. ISBN 978-3-16-142361-1 , p. 17.

- ^ Wilhelm Kubitschek: Outline of the ancient calendar. Beck, Munich 1928, p. 179.

- ^ Also Johan-Ludvig Heiberg: Claudii Ptolemaei, Almagest III. Vol. 1, Teubner, Lipsiae 1907, p. 205.

- ↑ S. Schott: Ancient Egyptian festival dates. Mainz / Wiesbaden 1950, p. 32.

- ↑ S. Schott: Ancient Egyptian festival dates . Mainz / Wiesbaden 1950, p. 31.

- ^ Klett-Verlag : Egyptian time measurement, workshop

- ↑ The name Streiflicht sundial comes from Ludwig Borchardt.

- ^ A b Ludwig Borchardt: Ancient Egyptian time measurement In: Ernst von Bassermann-Jordan (ed.) The history of time measurement and clocks. Leipzig / Berlin 1920, pp. 26–53.

- ↑ Ancient Egyptian timekeeping - Ancient Egyptian sundials: horizontal and wall clock . On: land-der-pharaonen.de ; last accessed on January 30, 2016.

- ↑ a b Portable sundial: UC 16376 . Image of the sundial sundial on: digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk from 2003; last accessed on January 30, 2016.

- ↑ Ludwig Borchardt described this clock as a sundial with a vertical collecting surface .