Stonewall

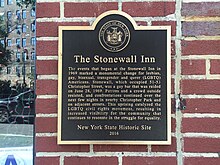

Stonewall , short for Stonewall Riot or Stonewall Riots , was a series of violent conflicts between gay and transsexuals and police officers in New York City . The first violent clashes took place in the early hours of Saturday, June 28, 1969. about 1:20 pm when police officers, who raided the Stonewall Inn conducted, a bar with gay and transsexual target audience in the Christopher Street at the corner of 7th Avenue in Greenwich Village .

As a significantly large group of homosexuals resisted arrest there for the first time, the event is viewed by the lesbian and gay movement as a turning point in their struggle for equal treatment and recognition. This event is remembered every year around the world with Christopher Street Day (CSD), which is usually called Gay Pride in English-speaking countries .

Summary

In the 1960s, there were repeated violent raids on gay bars in New York and other cities . The identity of the visitors to the pub was established and sometimes made public, and there were arrests and charges of "offensive behavior".

One such raid took place on the night of June 27-28, 1969 in the trendy bar Stonewall Inn . On that day, a particularly large number of gays are said to have been in New York because the funeral of actress Judy Garland , who was considered a "gay idol", had previously taken place. Visitors to the Stonewall Inn did not put up with the police and the officers were forcibly evicted.

The events led to widespread solidarity in the New York gay district, and in the days that followed, the gays successfully resisted the increased police forces. It took five days for the situation to calm down.

history

Police raids on gay bars and nightclubs were a regular occurrence in the gay scene across the United States until the 1960s, when such raids suddenly became much less common in major cities. It is believed that this was a result of a series of complaints in court and growing opposition from the lesbian and gay movement.

Before 1965, it was common for the New York police to record the identities of everyone present in such raids and sometimes publish them in the press, with devastating social consequences for those forcibly outed . Occasionally, as many customers as could fit in the police vehicles were also provisionally arrested. At the time, the police justified the arrests on indecency charges (such as "indecency" or " causing public nuisance"). This included kissing, holding hands, wearing clothes of the opposite sex or even just being in the pub during the raid.

In 1965 two important people came into the public eye. John Lindsay , a Liberal Republican , was elected Mayor of New York as a reformer . Around the same time, Dick Leitsch became chairman of the Mattachine Society , an early organization for the recognition of gay rights in the United States, in New York . Leitsch was seen as comparatively militant compared to his predecessors, and he believed in methods of direct action , which were very widespread among other civil rights groups in the 1960s.

In early 1966, the administration's policy changed due to complaints from Mattachine: Police used " decoy methods " to arrest people on the street on charges of "indecency". The police chief Howard Leary ordered that homosexuals should not be seduced into a crime by undercover police officers and that a civilian was necessary as a witness in the event of arrests by undercover people . This largely ended the arrests of homosexuals for these offenses.

That same year, Dick Leitsch challenged the State Liquor Authority (SLA) on guidelines that allowed a bar to be stripped of alcohol if it knowingly served alcohol to a group of three or more homosexuals. Leitsch organized a "Sip in", i. that is, he informed the press about his plan to meet two other gays in a bar. When the barman at the deliberate bar turned them down, they turned to the city's human rights commission. The chairman of the SLA then made it clear that his agency would no longer prohibit the serving of alcohol to homosexuals. In addition, two different court rulings found that “substantial evidence” was required to withdraw the liquor license and that kissing between men was no longer considered offensive. The number of pubs targeting homosexuals grew steadily after 1966.

In 1969 gay bars were legal, but the Stonewall Inn was raided that night. According to noted historian John D'Emilio , New York was in the middle of an election campaign for mayor and John Lindsay, who had just lost his party's primary election, believed it was necessary to "clean up" his city's pubs. The Stonewall Inn had a number of reasons the police were targeting it: the operators were not licensed, there were organized crime links , and scantily clad go-go boys were used to entertain the guests . The restaurant thus offered reason for the assessment that it would bring an “unruly element” (such as a rule violation ) to Sheridan Square. Marty Huber writes about the Stonewall Inn and its guests in Queering Gay Pride: “For one thing , the riots were an uprising from the bottom up, the Stonewall Inn bar - run by the Mafia - was a place where those who went to the back rooms could meet prestigious bars were not allowed in: homeless young people, Latinas and black drag queens, gay sex workers, butches and their lovers ... “Salih Alexander Wolter also supports this view from his studies and emphasizes that it was precisely these groups of people who fought most resolutely, including Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson .

The exclusion of the gay and lesbian community is evident from the customers of the Stonewall Inn. Racism is also said to have played a role in the police raids , as many blacks and Latinos frequented the Stonewall Inn . Perhaps the police's decision to carry out the raid the way it was ultimately carried out was influenced by the fact that the Stonewall Inn's customers were not only homosexual, but also largely ignorant and therefore particularly "despicable". A large proportion of the people who resisted were African American and Latinos.

Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine, who led the raid that night, claiming that he had been ordered to close the Stonewall Inn because it was the central location could collect on the one about homosexuals in the Wall Street worked . Previously, there was a spike in large-scale thefts from Wall Street traders , leading police to suspect that homosexuals might be involved in the thefts who were blackmailed about their homosexuality.

The raid and the aftermath

This raid brought together some factors that set it apart from the raids to which customers had become accustomed. Judy Garland , an important cultural icon with whom many homosexuals identified, had died a week earlier . The grief over the loss culminated in the funeral on Friday June 27, which was attended by 22,000 people, including 12,000 homosexuals. Many of the Stonewall's customers were still emotionally troubled when the raid took place. Historians argue about whether or not there was a connection.

Another thing that made the raid special was timing. Usually the operators of the bar from the Sixth District received a notice of the impending raid. The raids usually took place early enough in the evening so that the pub could continue to operate shortly after during peak business hours. This raid came much later than usual, at 1:20 a.m. on Saturday night.

Eight First Ward officials, only one in uniform, entered the establishment. Most customers were able to avoid arrest, as the only people who were typically arrested were those who did not have ID, people wearing clothes of the opposite sex and some or all of the bar staff.

The details of exactly how the uprising started are mixed. A source claims that a transgender woman named Sylvia Rivera threw a bottle at a police officer after she was hit by his baton. Another source claims that a lesbian woman ( Stormé DeLarverie ) resisted being put in a police car, encouraging the crowd to join her.

A brawl began in which the police were quickly overwhelmed. The officers withdrew to the bar. Straight folk singer Dave Van Ronk , who happened to be passing by, was caught by the police and mistreated in the bar. Some tried to set fire to the bar. Others used a parking meter as a battering ram to drive the police away. News of the brawl spread quickly, with more and more residents and customers from nearby bars flocking to the scene.

During that night, police arrested and mistreated numerous feminine-looking men. There were 13 arrests that night alone and four police officers were injured. The number of protesters injured is unknown. However, it is known that at least two people who resisted were seriously injured by the police. The protesters threw stones and bottles and chanted “Gay Power!”. The number of protesters was estimated at 2,000, against whom 400 police officers were used.

The police deployed reinforcements in the form of the Tactical Patrol Force , a unit that was originally trained to combat demonstrations by anti- Vietnamese opponents. The Tactical Patrol Force arrived and tried to disperse the crowd who attacked the police with stones and other projectiles. The situation eventually calmed down, but the protesters returned the next night. The protests were less violent than the first night. Smaller skirmishes between protesters and the police followed until around 4 a.m. that morning. The third day of protests came five days after the raid on the Stonewall Inn. This Wednesday, 1,000 people gathered at the bar and again caused significant property damage. Pent-up anger and outrage at the way homosexuals had been treated by the police for decades erupted.

The legacy

The forces that had simmered beneath the surface long before the uprising were no longer hidden. The community that had been created by gay-friendly organizations in the previous decades provided the ideal breeding ground for the open homosexual liberation movement. The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was formed in New York at the end of July , and by the end of the year it was represented in many cities and universities in the country. However, trans people and African-Americans were excluded from mainstream gays and lesbians - since 1973, trans people have no longer been allowed to be members of the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) - the successor organization to the GLF - because the clearly gendered gays and lesbians have better chances for an anti-discrimination law ( Gay Rights Bill) promised. Soon after, similar organizations were formed around the world, including Canada, France, Great Britain, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Australia and New Zealand.

The following year, the Gay Liberation Front organized a march from Greenwich Village to Central Park in commemoration of the Stonewall Riot . Between 5,000 and 10,000 people took part in this march. This established the tradition of Christopher Street Day (CSD), with which many gay pride movements have been celebrating the memory of this turning point in the history of discrimination against homosexuals. The Stonewall uprising also initiated a reorientation in the gay movement: While until then it was about the decriminalization of gays and lesbians and about promoting tolerance among the heterosexual majority of the population, a new self-confidence has been in the foreground since the uprising.

On June 24, 2016 proclaimed Barack Obama the Stonewall National Monument , a national memorial of the type of National Monuments .

See also

literature

- David Carter : Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked The Gay Revolution . St. Martin's Press, New York 2004, ISBN 0-312-20025-0 .

- John D'Emilio : Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1983, ISBN 0-415-90510-9 .

- Martin Duberman : Stonewall . New York 1993, ISBN 0-452-27206-8 .

- Eric Marcus : Making History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights, 1945–1990; An oral history. New York 1993, ISBN 0-06-016708-4 .

- Donn Teal: The Gay Militants: How Gay Liberation Began in America, 1969–1971. New York 1971, ISBN 0-312-11279-3 .

- Scott Bravmann: Queer Fictions by Stonewall. In: Andreas Kraß (Ed.): Queer Thinking. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-518-12248-7 .

- Dick Leitsch: Police Raid on NY Club Sets off First Gay Riot . In: The Advocate , September 1969, adapted from a New York Mattachine newsletter.

- Marty Huber: Queering Gay Pride: Between Assimilation and Resistance. Zaglossus, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-902902-06-1 .

- Salih Alexander Wolter: Stonewall revisited: A little history of movement In: Heinz-Jürgen Voss , Salih Alexander Wolter: Queer and (anti) capitalism. Butterfly Verlag, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-89657-061-1 .

- Tadzio Müller : Stonewall was a riot, jungle world , June 26, 27, 2019, p. 3 (also online).

Web links

- The film Stonewall in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Stonewall Veterans Association

- Stonewall and Beyond: Lesbian and Gay Culture

Individual evidence

- ↑ Martin J. Gössel: When the first coin flew and the revolution began. The Gay Movement in the United States in the Second Half of the 20th Century. A historical consideration and analysis . In: Edition Rainbow - Study Series . 1st edition. tape 3 . Graz 2009, ISBN 978-3-902080-02-8 , pp. 38 .

- ↑ D'Emilio, p. 207.

- ↑ Remembering a 1966 'Sip-In' for Gay Rights .

- ↑ D'Emilio, p. 208.

- ↑ D'Emilio, p. 231.

- ↑ Marty Huber: Queering Gay Pride: Between Assimilation and Resistance. Zaglossus, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-902902-06-1 , pp. 16 f, 113 ff.

- ^ Salih Alexander Wolter: Stonewall revisited: A little history of movement. In: Heinz-Jürgen Voss, Salih Alexander Wolter: Queer and (anti) capitalism. Butterfly Verlag, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-89657-061-1 , p. 28 ff.

- ↑ Carter, p. 262.

- ↑ Duberman, p. 192.

- ↑ Duberman.

- ^ Salih Alexander Wolter: Stonewall revisited: A little history of movement. In: Heinz-Jürgen Voss, Salih Alexander Wolter: Queer and (anti) capitalism. Butterfly Verlag, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-89657-061-1 .

- ↑ Storme DeLarverie, the Lesbian Who Started the Stonewall Revolution (interview). June 5, 2018, accessed July 2, 2020 .

- ↑ D'Emilio.

- ↑ Duberman, pp. 201-202.

- ^ Salih Alexander Wolter: Stonewall revisited: A little history of movement. In: Heinz-Jürgen Voss, Salih Alexander Wolter: Queer and (anti) capitalism. Butterfly Verlag, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-89657-061-1 , p. 31 ff.

- ^ "President Obama Designates Stonewall National Monument" (official announcement from White House Press Office; June 24, 2016)

Coordinates: 40 ° 44 ′ 1.8 ″ N , 74 ° 0 ′ 7.4 ″ W.