Svetlana Iossifovna Alliluyeva

Svetlana Alliluyeva , originally Svetlana Stalina Iossifowna ( Russian Светлана Иосифовна Аллилуева ; Georgian სვეტლანა იოსებინა ალილუევა * 28. February 1926 in Moscow ; † 22. November 2011 in Richland Center , Wisconsin ), was the youngest child and the only daughter of Soviet Government - and party leaders Josef Stalin and his second wife Nadezhda Allilueva .

Life

Like most of the children of the Soviet nomenklatura , Swetlana Stalina was raised by nannies from whom she learned German as her first foreign language. She only saw her parents occasionally. Her mother Nadezhda Allilueva died on November 9, 1932, when Svetlana Stalina was six and her brother Vasily eleven. The mother's death was officially portrayed as the result of appendicitis . Other theories see a suicide , a murder on behalf of Stalin or by his hand as the cause. Swetlana reported suicide in her memoir.

At the age of 16, Svetlana Stalina fell in love with the Jewish filmmaker Alexei Kapler (September 15, 1904 to September 11, 1979), winner of the Stalin Prize in 1941. Her father vehemently opposed the girl's relationship with the man who, who was more than 21 years her senior Stalin suspected that they were seeking advancement through them. Svetlana Stalina attributed Kapler's exile in 1944 to her father's hostility to Jews . She studied literature and American history. At the age of 17 she fell in love with her fellow student at Moscow University (and a former classmate of her brother Vasily) Grigori Morozov (1921-2001), who, like Alexei Kapler, was also a Jew . Joseph Stalin reluctantly allowed the marriage, but declared that he never wanted to meet the bridegroom. In 1945 the son Iossif Alliluyev was born. In 1947 the couple divorced. Grigori Morosow was later a professor at MGIMO and the son became a well-known cardiologist . Both were recognized as Honored Scientists of the RSFSR in their fields .

Svetlana Stalina's second husband was the philosopher and chemist Yuri Zhdanov (1919–2006), son of the Politburo member Andrei Zhdanov . They married in 1949 and had a daughter, Ekaterina, in 1950. The marriage ended in divorce in the fall of 1952.

After the death of her father in March 1953, Svetlana Stalina took her mother's surname and called herself Svetlana Allilueva. In Moscow she worked as a teacher and translator.

The third marriage attested by Svetlana Allilujewa's niece Galja and her friend Eleonora Mikoyan was Svetlana Alliluyeva with Ivan Svanidze (called Joni, Jonik, Jonrid after John Reed , author of the book about the October Revolution ). His parents were the opera singer Marija Swanidze (nee Korona) and the historian Alexander Swanidze , the brother of Stalin's first wife Ketewan Swanidze , called Kato. After his parents were killed in 1941, he grew up with their former housekeeper, who took him in. This marriage was never mentioned by Alliluyeva himself and it is not known whether children resulted from it.

From the end of the 1950s she worked as a literary scholar at the Maxim Gorky Literature Institute in Moscow. According to her autobiographical records, she defended works by Ilja Ehrenburg and Andrei Sinjawski that were critical of the regime at party meetings , but could not find a majority among the institute's staff. There she also read the forbidden works of Leon Trotsky about her father, Maxim Gorki's criticism of the bloody Kulturkampf of the Bolsheviks ( Untimely Thoughts on Culture and Revolution ), which was never published in the Soviet Union, as well as the original of the report on the October Revolution by John Reed ( Ten Days that shook the world ), in which her father is not mentioned at all, contrary to later Soviet editions. According to her own account, she was secretly baptized Russian Orthodox during this time .

In December 1966 she was allowed to travel abroad for the first time, to India . She had met an elderly Indian communist in a sanatorium who had come to the Soviet Union for treatment. According to her account, the two fell in love, but Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin personally told her that she would not get permission from the authorities to marry, let alone move abroad. When the already seriously ill Indian died in the Soviet Union, however, she got permission to visit his family in December 1966. Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko ordered their surveillance by the Soviet embassy in Delhi . Two days before the planned return flight, on March 6, 1967, she managed to evade her watchdogs. She reported to the US embassy in New Delhi and asked for asylum . She was first brought to Switzerland via Rome under the name "Miss Carlen" . She asked to speak to the American diplomat George F. Kennan , whose name she knew from the Soviet press; he had been repeatedly attacked as a sharp critic of the Stalin regime. After six weeks in two secret locations in the Swiss canton of Friborg ( St. Antoni and Friborg ), where she was baptized Orthodox in the ecumenical-orthodox church of Friborg, according to the then rector of the pilgrimage church Notre Dame de Bourguillon ( Bürglen ) , she flew to the USA and initially stayed at the Kennans estate. She made friends with him and his family. She received the status of a simple immigrant.

In the USA she wrote two autobiographical books that were published by American publishers and became bestsellers. They have been translated into many languages but were banned in the Soviet Union. In the volume "Only One Year" she gave her father the responsibility for the murder of the Polish prisoners-of-war in the Katyn forest in the spring of 1940 and asked whether he had had remorse as a result.

In 1970 she married the architect William Wesley Peters (1912–1991), with whom she had a daughter, Olga, in 1971. In 1973 the couple divorced.

In 1982 she moved to Cambridge with her daughter . In 1984 she returned to the Soviet Union and lived for several years in Georgia's capital Tbilisi . A violent feud soon broke out with her Georgian relatives. In 1986 she sent her 15-year-old daughter Olga back to the West. The daughter attended a school in Saffron Walden near Cambridge in Great Britain .

In the late 1980s, Svetlana Alliluyeva moved to the United Kingdom . According to her own statements, she was impoverished in 1990 and lived with her daughter in a rented house in Bristol . In 1996 Swetlana moved back to the USA. She took the last name of her ex-husband Peters. Most recently she lived as Lana Peters in a retirement home in Richland Center , Wisconsin , not far from her temporary residence with Peters, who was chairman of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in his summer residence, Taliesin , until his death .

Fonts

- 20 letters to a friend . Molden, Vienna 1967.

- The first year . Molden, Vienna 1969.

literature

- Martha Schad : Stalin's daughter. The life of Svetlana Allilujewa. Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 2004, ISBN 3-7857-2158-7 .

- Nicholas Thompson: My Friend, Stalin's Daughter: The Complicated Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva . In: The New Yorker, March 31, 2014, pp. 30-37.

- Rosemary Sullivan, Stalin's daughter. The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva. New York 2015. ISBN 978-1-4434-1442-5 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Swetlana Iossifowna Allilujewa in the catalog of the German National Library

- Always fleeting ; Article in Der Spiegel of November 5, 1984

- A monster to the father. In: NZZ Online from November 29, 2011

- Diplomatic documents on Svetlana Alliluyeva's stay in Switzerland in 1967

Individual evidence

- ^ Douglas Martin: Lana Peters, Stalin's Daughter, Dies at 85 ; Article in the New York Times on November 28, 2011.

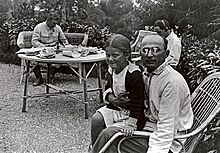

- ↑ Eva Clifford, et al .: 1001 photographies qu'il faut avoir vues dans la vie; La fille de Staline sur les genoux de Beria . Ed .: Paul Lowe. Éditions Flammarion, Paris 2018, ISBN 978-2-08-142221-6 , pp. 289 (Original Edition : 1001 Photographs You Must See In Your Lifetime , Quintessence Edition, 2017).

- ↑ Der Spiegel 39/1967 printed part of it (translated): [1]

- ↑ Always fleeting ; Article in Der Spiegel of November 5, 1984

- ↑ Svetlana Allilueva: Odin god dočeri Stalina. New York 1969, pp. 33-36.

- ↑ Svetlana Allilueva: Odin god dočeri Stalina. New York 1969, pp. 27-30.

- ^ Jean-Christophe Emmenegger: "Opération Svetlana": Les six semaines de la fille de Staline en Suisse . 1st edition. Éditions Slatkine & Cie., Chavannes-de-Bogis (Suisse) 2018, ISBN 978-2-05-102819-6 , pp. (Monograph) .

- ^ Jean-Claude Goldschmid: Mrs. Staehelin in the Freiburgerland. In: Freiburger Nachrichten . April 18, 2018, accessed May 19, 2020 .

- ↑ Josiane Ferrari-Clément: Miracles et pèlerinages au Pays de Friborg - Ils ont reçu parce qu'ils ont cru . In: Archives vivantes . Éditions Cabédita, Bière (Suisse) 2019, ISBN 978-2-88295-862-4 , p. 104 f .

- ↑ John Gaddis: George F. Kennan. American Life. New York 2011 .

- ↑ Douglas Martin, Lana Peters, Stalin's Daughter, Dies at 85 , in: New York Times , November 28, 2011

- ↑ Svetlana Alliluyeva; Paul Chavchavadze (translator): Only One Year. New York 1969 / Svetlana Allilueva: Odin god dočeri Stalina. New York 1969, p. 77.

- ↑ a b c BBC News: Stalin's daughter Lana Peters dies in US of cancer

- ^ Martha Schad: Visiting Stalin's daughter ; from Cicero 4/2005 on GeorgienSeite.de.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Alliluyeva, Svetlana Iossifovna |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Stalina, Swetlana; Аллилуева, Светлана Иосифовна (Russian); Peters, Lana |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian teacher, daughter of Josef Stalin |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 28, 1926 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Moscow |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 22, 2011 |

| Place of death | Richland Center , Wisconsin |