Diving medicine

The diving medicine is a branch of occupational medicine and sports medicine and a central part of dive training . It deals with medical research on questions of diving , the prevention and treatment of diving accidents and diving fitness . This includes the effect of gases under increased pressure on the human body, the detection and treatment of injuries or poisoning that occur in the water or when entering or exiting the water, as well as the connections between the health of a diver and his safety. There is also a relevant psychological side of diving medicine. In diving accidents, multiple trauma can often occur at the same time and influence one another.

Hyperbaric medicine

Main field of diving medicine is the hyperbaric medicine , even hyperbaric called. It deals with the consequences of changes in physical conditions to which a diver is exposed underwater. Decompression sickness and barotrauma are the most common trauma in accident divers.

decompression sickness

Due to the increased ambient pressure , larger quantities of the inert gases contained in the breathing gas go into solution in the body than at normal pressure ; Inert gases are - depending on the breathing gas - nitrogen , helium , neon or argon . As you ascend the pressure is reduced and decompression occurs ; if this happens too quickly, the gases bubble out in the body. The resulting tissue tears and gas embolisms lead to decompression sickness ( DCS for short ). The symptoms range from harmless complaints such as itching of the skin ( diving fleas ) through impaired consciousness and paralysis to death. Chronic damage to professional divers is also possible. Therapy is initially given with the fastest possible administration of pure oxygen . If necessary, the patient is exposed to the original, higher pressure in a decompression chamber . The pressure is then slowly reduced so that the dissolved gases can be exhaled through the lungs.

Toxic effects of breathing gases

Under increased pressure, the biological effect of the gases in the natural air you breathe changes. Nitrogen has a narcotic effect and can cause so-called deep intoxication. Oxygen becomes toxic in high concentrations and under high pressure and can cause central nervous symptoms such as tunnel vision, ringing in the ears, nausea, dizziness, vomiting, personality changes, excitement, fear, confusion and cramps during diving. this is known as oxygen poisoning . Accordingly, diving medicine also deals with gas mixtures for use at different depths and for different durations of the dives up to a permanent supply of underwater houses with breathing gas mixtures that contain proportions of rapidly diffusing helium or other noble gases such as argon as a nitrogen substitute.

Barotrauma

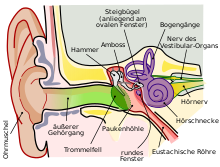

The pressure in the air-filled body cavities, mainly the lungs, the middle ear , the paranasal sinuses and the frontal sinuses , has to adapt to the changed pressure conditions of the environment when diving; this is described in Boyle-Mariotte's law.

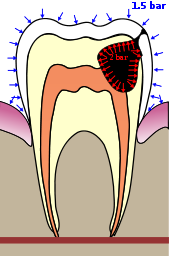

As you descend, compression increases the pressure in the middle ear. If this pressure cannot be adjusted via the ear trumpet and no pressure compensation can be established, the eardrum bulges inwards. It can bleed in or tear. The air expands as a result of the pressure reduction when ascending. If the pressure cannot escape from the lungs - for example because of a vocal cord spasm or if you hold your breath on the ascent - the lungs can tear with subsequent air embolism , which can be fatal. In addition to the physiologically air-filled cavities in the body, air pockets under dental fillings or in carious teeth can also cause discomfort. Barotrauma of the skin is less common , for example caused by the seam of a dry suit that compresses a point for a long time from the ambient pressure. The treatment of barotraumas is varied: It ranges from the simple regulation of diving bans, drug treatment or the replacement of dental fillings, to complex surgical interventions in the skull or thorax area. As a sensible emergency measure in the event of barotrauma of the lungs, it is recommended to give pure oxygen for breathing.

Other medical problems

In addition to the specific problems directly caused by diving, other emergencies and medical problems fall within the scope of diving medicine. They can differ depending on the location and the climatic zone.

Heat balance

Another important field of work and research in diving medicine deals with the heat balance ( thermoregulation ) of divers. The human body gives off more heat when it is surrounded by water - colder than body temperature - instead of air, which is why a diver cools down quickly if he is not protected by a diving suit . Even then, the insulating effect decreases with increasing depth due to compression of the suit material, which can not be completely prevented even when using a dry suit ; only heat conduction can be minimized, but not heat loss through convection .

The thermal conductivity of gases increases with their density. In the depths, the diver breathes compressed, denser air that is warmed up in the lungs. That is why he loses more heat just by breathing than by contact with the surrounding water. In addition, the inhaled air is dry and cold because of the pressure relief that took place shortly before when it was removed from the high pressure bottle; the exhaled air is always saturated with water vapor and has a temperature of 37 ° C. This effect is not compensated by any of the usual equipment used by recreational divers. Possible consequences are, even in tropical waters, spasms in the limbs and hypothermia (hypothermia).

Poisoning

Poisoning by cnidarians , starfish , sea urchins , octopuses , poisonous fish or amphibians occurs mainly in warm waters. Usually these are neurotoxins which, depending on the animal, can only be painful or even fatal. Effective antidotes are known only for a few species; some poisons are effective very quickly, which is why z. B. in the case of poisoning with a large amount of nettle poison from the box jellyfish Chironex fleckeri, there is only very little chance of survival.

However, anaphylaxis to a marine toxin is more common than the actual toxic effect.

Essoufflement

A diver has to work harder to get enough oxygen, depending on the depth and often because of a tight diving suit . The breathing resistance increases due to the increased ambient pressure at greater depths. This causes the respiratory muscles to tire and the breathing becomes shallower. The body reacts to this with an increased breathing rate and the diver falls into tachypnea . Due to the increasing respiratory rate with a simultaneous shallower breathing, carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) can no longer be fully exhaled. An essoufflement gradually develops , which ultimately leads to carbon dioxide poisoning and serious disturbances up to and including unconsciousness . A short rest and conscious, calm breathing usually make the symptoms of an essouflement disappear.

Covid-19

If you have a Covid-19 disease, it is advisable to undergo a diving fitness test before the next dive, as the disease can lead to deformities in the lung tissue.

Psychology in diving

Divers are exposed to many environmental influences in the water, which can also have a psychological effect. Due to limited visibility , low temperatures , currents , aquatic animals perceived as threatening or after diving accidents, a diver can get psychological problems. In many cases, an accident diver or his buddy blames himself for acting differently than he learned to do. Often repressed anxiety also plays a role, and it can become so severe that physical symptoms appear, for which a diving doctor is consulted. In such cases, the diving doctor is required to recognize this and, if necessary, to arrange for cooperation with a psychologist . If a diving doctor has to recommend a diver to give up diving for medical reasons, this can result in strong emotions or even completely ignoring the recommendation, as quite a few divers associate numerous memories, dreams or even an entire life plan with diving.

Gender specific

During menstruation , diving can be done without any problems, according to the general recommendations, provided the woman does not feel very physically weakened. A study by the US Air Force in a decompression chamber found a 4.3 times higher risk of decompression sickness (DCS) during menstruation. So far, however, these results could not be reproduced in divers. Contrary to rumors, there is also no scientific evidence that menstruating women would attract sharks or other potentially dangerous marine life. On the contrary, it appears that the vaginal secretions drive away sharks. A danger when diving during menstruation is the penetration of small amounts of sanded seawater and thus pathogens into the vagina, which can cause vaginal inflammation . A commercially available tampon usually effectively prevents the penetration of such germs.

It is recommended that you avoid diving while pregnant . There is no scientific certainty that the increased ambient pressure while diving is safe for an unborn child.

Further problems

Since there is always the risk of swallowing water while diving, a diving doctor should also be familiar with diseases that arise from contaminated water. For example, water contaminated with E. coli bacteria can cause serious diseases.

Furthermore, in tropical climatic zones the risk of wound infection is increased, even with minor injuries, and there is a general risk of infection with tropical diseases and the risk of infestation with human parasites .

Diving fitness

Physical health is an important requirement for diving. Therefore, many diving schools and associations require a diving suitability test before they allow a recreational diver to take a diving course . Not infrequently, a diving suitability examination is required on diving boats and diving centers, which should not be older than two to three years and should be carried out annually from the age of 40 or under the age of 18. For professional divers, the diving fitness test is regulated by law and must be carried out annually. Even after a diving accident, your fitness to dive should be reassessed by a diving doctor.

The diving fitness test serves to prevent diving accidents and should be in the self-interest of every diver. The examination gives the doctor the opportunity to make it clear to a diver what his limitations are or that diving poses too great a risk for him. The diving doctor clarifies the following points in a conversation or through a questionnaire:

- Is the patient physically able to swim longer distances?

- Can the patient communicate appropriately and clearly with other people?

- Does he have the necessary degree of mental maturity and personal responsibility ?

- Are there reasons why a sudden loss of consciousness or disorientation can be expected?

- Are there reasons that sudden panic could arise?

- Are there physical causes that could promote barotrauma?

- Could addictive substances impair the ability to dive?

- Does the patient have any illness or predisposition that diving may make worse?

In addition to the general condition, the doctor examines the following areas during the diving fitness examination :

- Heart ( blood pressure , pulse , auscultation )

- Lungs (auscultation, pulmonary function test )

- Ears and sinuses

- Performance (resting / stress ECG )

- Very obese people further investigation may be added, as strong Obesity may limit the diving fitness.

- Depending on the age, the overall condition and the examination results, further special examinations such as X-ray examination of the chest ( thorax ), ergometry or laboratory tests ( blood count , serum examination, erythrocyte sedimentation reaction ESR , urine examination) may be necessary.

education

The guidelines for the use of the additional designation diving physician, for training and further education and for diving suitability examinations are published in Germany by the Society for Diving and Overpressure Medicine (GTÜM). In Switzerland, the Swiss Society for Underwater and Hyperbaric Medicine (SUHMS) is responsible, in Austria the Austrian Society for Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine (ÖGTH). Trained as a diving medical incumbent in the United States the National Board of Diving and Hyperbaric Medical Technology (NBDHMT).

The global umbrella organization for diving medicine is the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society (UHMS).

literature

- S2k guideline diving accident of the society for diving and hyperbaric medicine . In: AWMF online (as of 2011)

- Christoph Klingmann (Hrsg.), Kay Tetzlaff (Hrsg.): Modern diving medicine: manual for diving instructors, divers and doctors. 2nd Edition. Gentner Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-87247-744-6 .

- Claus-Martin Muth, Peter Rademacher: Compendium of diving medicine: Introduction and overview for general practitioners and sports physicians. 2nd Edition. Deutscher Ärzteverlag, 2006, ISBN 3-7691-1239-3 .

Web links

- Society for diving and hyperbaric medicine e. V. Germany

- Swiss Society for Underwater and Hyperbaric Medicine

- Austrian Society for Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g P. Nussberger, P. Knessl, C. Wölfel, S. Tort: Tauchmedizin - an overview , part 2. (PDF; 676 kB) In: Schweiz Med Forum , 2007 (7), p 990-993; accessed on March 14, 2013.

- ^ Claus-Martin Muth, Peter Rademacher: Compendium of diving medicine: Introduction and overview for general practitioners and sports medicine . 2nd Edition. Deutscher Ärzteverlag, 2006, ISBN 3-7691-1239-3 , p. 1-17 .

- ↑ Diving accident . Emergency medicine / emergency care: diving accident, decompression trauma from notmed.info, accessed on March 11, 2013.

- ↑ decompression sickness (PDF; 108 kB), todi.ch; Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ↑ Thomas Kromp , Hans J. Roggenbach, Peter Bredebusch: Practice of diving . 3. Edition. Delius Klasing Verlag, Bielefeld 2008, ISBN 978-3-7688-1816-2 .

- ↑ a b Barotrauma , todi.ch; Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ A b Claus-Martin Muth, Peter Rademacher: Compendium of diving medicine. 2nd Edition. Deutscher Ärzteverlag, 2006, ISBN 3-7691-1239-3 , pp. 13-14.

- ↑ a b temperature and thermal conductivity. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on February 14, 2014 ; Retrieved May 19, 2011 .

- ^ Peter J. Fenner: Dangers in the Ocean: The Traveler and Marine Envenomation. I. Jellyfish. Journal of Travel Medicine, 5 (3): 135-141 1998 doi: 10.1111 / j.1708-8305.1998.tb00487.x

- ↑ Philipp Alder charging: The Cubozoan - Chironex fleckeri .

- ↑ P. Nussberger, P. Knessl, C. Wölfel, S. Tort: Tauchmedizin - an overview, part 1 . (PDF; 374 kB), Schweiz Med Forum 2007 (7), pp. 970–974, accessed on March 14, 2013.

- ^ Claus-Martin Muth: Essoufflement. (PDF) (No longer available online.) German Life Saving Society, archived from the original on April 2, 2015 ; accessed on March 23, 2017 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Diving after COVID-19 infection - pulmonologist: check for suitability after a severe course. Retrieved on May 2, 2020 (German).

- ^ A b Prof. JJ McComb: Menstruation and diving. In: Underwater Journal. No. 3/2002, pp. 46-48

- ↑ a b c Katharina Becker: Diving despite your period? What you should know about diving and the rules. Diverettes Herzogenrath, July 22, 2015, accessed September 8, 2017 .

- ↑ Samuel Shelanski: Diving and menstruation. Separating fact from fiction. (No longer available online.) In: Scuba Diving Mag. Rodale Press Inc., February 21, 2002, archived from the original on February 21, 2002 ; accessed on September 8, 2017 (English).

- ↑ Divers FAQ. Can I dive while pregnant? dive.steha.ch, accessed on April 17, 2020 .

- ↑ Walter Siegenthaler (Ed.): Siegenthaler's differential diagnosis: internal diseases - from symptom to diagnosis. 19th edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, 2005, ISBN 3-13-344819-6 , pp. 173-174.

- ↑ R. Marre, Th. Mertens, M. Trautmann, W. Zimmerli (eds.): Clinical Infectious Diseases: Recognizing and Treating Infectious Diseases. 2nd Edition. Urban & Fischer, Ulm / Stuttgart / Liestal 2008, ISBN 978-3-437-21741-8 , p. 30.

- ↑ Fitness for diving . GTÜM e. V., BG-Unfallklinik Murnau office; Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ↑ Information about fitness for diving . the GTÜM and ÖGTH.

- ↑ GTÜM / ÖGTH examination form . (PDF; 52 kB) GTÜM e. V. - BG-Unfallklinik Murnau office; Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ↑ The diving fitness test . ( Memento of the original from July 7, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. tcneptun.ch; Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ Medical check-ups for recreational divers . of the GTÜM and ÖGTH, p. 4.

- ↑ Further training guidelines of the GTÜM e. V. for diving & hyperbaric medical qualifications of doctors accessed on June 23, 2011.

- ↑ courses (English) SUHMS; Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ↑ Training / further training guidelines. ÖGTH; Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ↑ Who we are . at nbdhmt.org, accessed March 14, 2013.

- ^ Constitution and By-Laws of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society, April 2009; accessed on March 14, 2013.