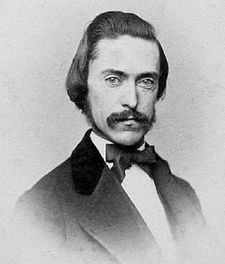

Theodore Nicholas Gill

Theodore Nicholas Gill (born March 21, 1837 in New York City , † September 25, 1914 in Washington ) was an American ichthyologist and malacologist . He was an associate member of the Smithsonian Institution for over 50 years .

Life

Theodore Nicholas Gill was born in a house on Broadway in Manhattan , but soon moved to Grand Street, on the outskirts of the then only 300,000-inhabitant city, where the open natural landscape with fields and forests began.

His father determined his son to pursue a career as a clergyman and, after briefly attending a prestigious grammar school , sent him to a private tutor in order to secure him a good education, especially in classical philology . After Theodore Nicholas Gill's mother died, his father remarried and moved to Brooklyn . From then on, the young Theodore went to school again in the city and had to take the ferry from Brooklyn to the mainland every day, where he passed one of the largest fish markets in the world, the Fulton Fish Market , near the overseas port . His interest in fish was soon aroused, but a scientific career was out of the question for him in the situation at the time.

Gill therefore decided to avoid the unpopular career as a clergyman and start studying law in order to later find a job with an uncle in a law firm. His real interests, however, were science and nature .

At the time, studying science offered few opportunities for employment, but Gill received a scholarship at the Wagner Free Institute in Philadelphia PA , where he could pursue his interests further. He began to expand his scientific acquaintances, and in 1856 met the mollusk zoologist William Stimpson (1832–1872) in New York, who had just come back from the North Pacific Exploring Expedition and was working on the Smithsonian . Stimpson returned to Washington and told Spencer Fullerton Baird (1823–1887) about the young scientist. Baird and Gill were known correspondence with each other, and Baird arranged the publication Gills report on fish of New York in the Smithsonian Annual Report 1856. In December the following year traveled Gill Washington to his expedition in the Caribbean prepare. There he met Baird personally and the Secretary of the Smithsonian Joseph Henry (1797-1878). That was the beginning of a lifetime membership in the Smithsonian Institution.

Gill came back from the Caribbean with an important collection , including some sea fish from Trinidad . In August 1858 he went to Washington to process his collection, which has been deposited at the Smithsonian. In 1859 he made a second trip, this time to Newfoundland , to help his grandfather build his estate. These two trips were the only significant fieldwork he has ever undertaken. He spent the rest of his career studying the ever-growing collections in the museum.

After returning from Newfoundland , Gill was chosen by Baird to help process the results of the Northwest Boundary Survey . In 1862, Gill was appointed in charge of the Smithsonian Library. When this library was integrated into the Library of Congress (Washington) in 1866 , Gill was taken over and appointed as Assistant, later as Senior Assistant Librarian of Congress, which he held until 1874. In addition to his career at the Smithsonian, he was a long-time scientific member at Columbian College in Washington, now George Washington University . Gill started there in 1860 as a deputy professor and became a lecturer in 1864, professor in 1884 and professor emeritus in 1910. During this time he earned four degrees from the university:

- 1865 Master of Arts

- 1866 Doctor of Medicine (honorary)

- 1870 Doctor of Philosophy

- 1895 Doctor of Laws

Still, Gill was a less than inspired lecturer and showed little interest in administrative matters or day-to-day work on the collections. In fact, early in his career he made it clear to Baird that after changing Smithsonian's fish collections three times, he wanted nothing more to do with it. Gill was a prolific writer, editing more than 500 manuscripts in his long career. It was mainly about fish (388), but he also wrote about birds , mammals and molluscs, as well as theoretical and general biology . For a while he edited the ornithological magazine The Osprey . Gill was very interested in animal relationships and taxonomy . He used osteology and other similar sciences in his studies. As a result, Gill's works had a very distinct point of view on it than other taxonomic descriptions in that era. His work has always been based on careful observation, but it has all been kept short and sweet. He preferred to work on smaller groups first and then put the results on paper. Many of his earlier manuscripts are featured in the Annals of the New York Lyceum of Natural History (he joined the Lyceum in 1858) and the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (the Academy selected him as correspondent in 1860 ). After the Proceedings of the United States National Museum began publishing in 1878, most of Gill's manuscripts appeared there. Among the most influential works was his Taxonomy of Fish (1872), which was based on the Smithsonian fish collections and which most ichthyologists used as a template for many years afterwards.

Although Gill never married and spent much time in his Smithsonian Institution accommodation, he was by no means a hermit. He divided his life equally into science and society. He was a member of many scientific societies, such as the American Association for the Advancement of Science (Washington), of which he became a Fellow in 1875 and of which he was President in 1897. Since 1867 he was an elected member of the American Philosophical Society . In 1873 he was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences (Washington). Gill was greatly honored and respected by his colleagues. David Starr Jordan even adored Gill with respect, calling him a Master of Taxonomy and the most passionate interpreter of taxonomic facts ever in the history of ichtyology . Gill volunteered his time to provide his scientific colleagues and the public with help and advice. He has written articles in encyclopedias and other public works, including an interview with the Washington Post about sea fish. Weakened by a stroke , Gill spent his final years quietly in Washington , where he died on September 25, 1914.

Fonts

- Catalog of the fishes of the eastern coast of North America, from Greenland to Georgia. Philadelphia 1861.

- Arrangements of the Families of Mollusks 1871.

- Arrangement of the Families of Mammals 1872.

- Material for a bibliography of North American mammals. Washington 1877.

- Günther's literature and morphography of fishes. Forest and Stream, New York 1881.

- Scientific and popular views of nature contrasted. Judd & Detweiler, Washington 1882.

- Addresses in memory of Edward Drinker Cope. Philadelphia 1897.

- A remarkable genus of fishes, the umbras. Smithsonian, Washington 1904.

- Angler fishes. 1909.

- Notes on the structure and habits of the wolffishes. Washington 1911.

literature

- William Healey Dall (1845-1927): Biographical Memoir of Theodore Nicholas Gill, 1837-1914. In: Biographical Memoirs , vol. 8, pp. 313-343, National Academy of Sciences, Washington 1916

Individual evidence

- ↑ Historic Fellows: Theodore Gill. American Association for the Advancement of Science, accessed August 20, 2018 .

- ^ Member History: Theodore Nicholas Gill. American Philosophical Society, accessed August 20, 2018 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gill, Theodore Nicholas |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American ichthyologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 21, 1837 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | New York City |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 25, 1914 |

| Place of death | Washington, DC |