Transi

The Transi is a special form of grave sculpture, mostly on grave slabs over sarcophagi or cenotaphs . As is usual with tombs with a reclining figure ( Gisant ), the deceased is depicted lying on his back. Below the (intact, and often magnificently decorated) reclining figure, the naked or half-naked body of the deceased is represented a second time as a corpse in all possible stages of decomposition . Erwin Panofsky also called this form of the tomb a "double-decker tomb". With the designation "double-decker tomb" Panofsky refers to the study "The King's two Bodies" by the historian Ernst Kantorowicz and introduces the idea of the two bodies of the king into the iconology of grave sculpture. Andrea Baresel-Brand discussed the genesis, reception and problems of this term in her study of northern European princely tombs. This depiction of the second body as a decaying corpse with macabre details shows parallels to the depictions of the dance of death, which were particularly popular in the late Middle Ages . The first tombs with a transit point appeared towards the end of the 14th century and spread from France over large parts of Europe. The motif's popularity peaked in the 15th and 16th centuries, but persisted well into the 17th century, especially in Italy and Spain.

development

14th Century

The cultural historian Johan Huizinga attributes the emergence of the Transi to the moral crisis that gripped people during the Black Death and the Hundred Years War . Probably the oldest preserved tomb with a transi is in the chapel of Saint-Antoine (or Jaquemart, around 1390) in La Sarraz ( Canton of Vaud , Switzerland). This is the cenotaph of the founder, François I de La Sarra, who died in 1363 and who consecrated the chapel to Saint Anthony as the patron saint against the plague. In contrast to the surrounding statues of praying ladies and knights, the deceased lying there with crossed arms is shown naked. The face and genitals are each covered by four toads , the rest of the body by snakes, symbolic animals of sin and lust . Another early example is the grave of the famous doctor Guillaume de Harsigny († 1393) in Laon (Picardy). The toothless, skeletal, emaciated old man is portrayed as at the time of his death, and not at the age of thirty-three, as was usually done with regard to the hoped-for resurrection . He no longer folds his hands in prayer, but only tries to hide his dried up sex with them.

15th century

After Cardinal Jean de La Grange († 1402) had himself depicted in the Church of Saint-Martial in Avignon with a dry, uncovered corpse underneath his grave slab, this type of grave sculpture became particularly popular among high clerical dignitaries as well as members of the nobility. An inscription admonishes the viewer not to pray for the dead, but instead to show humility , because: “Soon you will be like me, a hideous corpse, devoured by worms. Well, wretches, what is the reason for the pride ? ”An investigation by Kathleen Cohen into the living conditions of five French clergymen who had commissioned a tomb with a transi showed that the clients could look back on great successes during their lifetime .

Not only members of the clergy, but also wealthy citizens such as the bookseller and alchemist Nicolas Flamel († 1418) “decorated” his gravestone in Paris with a simple relief of his own, skeletonized corpse. Today it is in the Musée de Cluny .

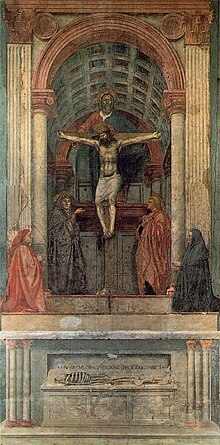

As early as the beginning of the 15th century, tombs with a transi also spread in England. Masaccio's fresco Trinity in Santa Maria Novella (1425–1427) shows a sarcophagus with an anatomically correct skeleton in an illusionistic grisaille technique ; Strictly speaking, however, it is not a transit or double-decker tomb.

In the tombs that Erwin Panofsky called “double-deckers”, Gisant and Transi were connected to one another: on an upper, stone bier the deceased is shown as in his lifetime, either lying or kneeling during prayer, underneath again as an outstretched corpse, with or without a shroud, sometimes already covered with worms and other scavenging animals. An example of this is the tomb of John FitzAlan , 14th Earl of Arundel († 1435).

In France there is also the well-known Transi of the doctor and canon Guillaume Lefranchois (after 1446) from Béthune (today in the Museum of Fine Arts in Arras , Pas-de-Calais).

In Germany, the type of the double-decker grave with Transi was introduced with the tomb of Trier Archbishop Jakob von Sierck in the Trier Church of Our Lady , which was created around 1455/62 . Today only the upper plate with the figure of the archbishop in official costume has been preserved. The two-part grave of the Palatinate Elector Friedrich the Victorious (died 1476) from around 1467, formerly in the Franciscan monastery in Heidelberg, which was demolished around 1805, was completely lost .

16th Century

In the aristocratic circles, the “double-decker” tomb eventually even developed into “double-decker” for married couples. In the cathedral of Saint-Denis , the burial place of the kings of France, outside of Paris, elaborate Renaissance monuments for Louis XII. († 1515) and his wife Anne de Bretagne († 1514), as well as for his successor Franz I († 1547) and his wife Claude de France († 1524). On these the monarchs were depicted above in a kneeling position praying, below as corpses, even if still untouched by decay.

The Transi des René de Chalons († 1544) by Ligier Richier , in the Saint-Étienne church in Bar-le-Duc , Lorraine, is unusual in some ways . Instead of lying on its grave slab, the decaying corpse stands upright on a small pedestal and holds its own heart in its hand, which it holds out towards the sky with an expressive gesture. Otherwise, similar representations of upright skeletons, such as B. on a church pillar in Albinhac , interpreted more as an allegory or personification of death itself, and not as the "portrait" of a deceased. Probably precisely for this reason the Transi des René de Chalons became so well known that the sculptor and animal painter Edouard Ponsinet (known as Pompon) made a copy for the tomb of the poet Henry Bataille in Moux ( Aude ) in 1922.

Tombs in the late Gothic style can still be found in the sixteenth century. B. on a Transi in the church Saint-Gervais et Saint-Protais (around 1526) in Gisors (Upper Normandy). Likewise, John Wakeman († 1549), the last abbot of Tewkesbury (Gloucestershire), had his cenotaph decorated with tracery in the late Gothic perpendicular style . The transit of Johann III. von Trazegnies and his wife Isabel von Werchin (1550), in the church of Saint-Martin in Trazegnies (Hainaut, Belgium) is still designed in the traditional way: on top of the grave slab, which is supported by columns hung with coats of arms, lies the couple, underneath a plate depicting a single skeleton. This is wrapped by banners with Gothic script. Here you can read: Mors omnia solvit. Nascentes morimur, Mors ultima linea rerum. Ortus cuncta suos repetunt matremque requirunt, Et redit ad nihilum quod fuit ante nihil. The Transi, designed around the same time by Jacques Du Brœucq for Herr von Boussu , on the other hand, already seems almost mannerist .

Transi des Nicolas Roeder, Strasbourg Alsace, 1510.

Tomb of Louis XII. and Anne of Brittany .

L'Homme à moulons (The Worm Man), Boussu (Belgium)

See also

literature

- Françoise Baron: Le médecin, le prince, les prélats et la mort. L'apparition du transi dans la sculpture française du Moyen Âge. In: Cahiers archéologiques. Numéro 51. Paris 2003, pp. 125-158.

- Andrea Barsel-Brand: funerary monuments of northern European royal houses in the Renaissance era, 1550–1650 . Kiel 2007.

- Kathleen Cohen: Metamorphosis of a Death Symbol: The Transi Tomb in the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance (Berkeley: University of California Press), 1973.

- Erwin Panofsky: Grave sculpture: four lectures on their change of meaning from Ancient Egypt to Bernini (from the English: Tomb Sculpture (New York) 1964: 65); Cologne, DuMont, 1964 "

Web links

- L'Automne des Transis , exposure

- Représentation du corps - Le transi ( Memento of March 27, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) by Geneviève Bresc Bauthier [Bresc-Bautier] Conservateur du Musée du Louvre

Individual evidence

- ^ Erwin Panofsky: grave sculpture. Four lectures on their change of meaning from Ancient Egypt to Bernini. Cologne: DuMOnt, 1964.

- ↑ Andrea Barsel-Brand: funerary monuments of northern European royal houses in the age of the Renaissance, 1550-1650 . Kiel, 2007.

- ^ Philippe Ariès, Essais sur l'histoire de la mort en Occident du Moyen-Age à nos jours , Paris, Seuil, 1975

- ^ Johan Huizinga: Autumn of the Middle Ages. Studies of forms of life and minds of the 14th and 15th centuries in France and the Netherlands, translated into German by Tilli Jolles Mönckeberg. Munich: Drei Masken Verlag, 1924.

- ↑ Frog and King (PDF; 2 MB)

- ↑ Utzinger (Hélène et Bertrand), Itinéraires des Danses macabres , éditions JM Garnier, 1996 , ISBN 2-908974-14-2 .

- ↑ Kathleen Cohen: Metamorphosis of a Death Symbol: The Transi Tomb in the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance (Berkeley: University of California Press), 1973.

- ^ Gravestone of Nicolas Flamel

- ↑ Pamela King: "The cadaver tomb in the late fifteenth century: some indications of a Lancastrian connection", in Dies Illa: Death in the Middle Ages: Proceedings of the 1983 Manchester Colloquium , Jane HM Taylor, ed.

- ^ Erwin Panofsky: grave sculpture: four lectures on their change of meaning from ancient Egypt to Bernini (from the English: Tomb Sculpture (New York) 1964: 65); Cologne, DuMont, 1993; ISBN 3-7701-3123-1 .

- ↑ Transi des Guillaume Lefranchois

- ↑ restoration you transi de René de Chalon

- ↑ Transi in Albinhac in the Google book search

- ↑ Transi in Gisors

- ↑ Notice descriptive et historique des principaux chateaux in the Google book search. Death dissolves (cancels) everything. In being born we (already) die. Death is the ultimate goal of all things. Everything strives back to its origin and seeks the mother, and it returns to nothing that was nothing before.

- ↑ In the Flemish patois moulon means made ( Dictionnaire du patois de la Flandre in the Google book search) or worm ( Mémoire historique et descriptif sur l'église de Sainte-Waudru in the Google book search)