Senate of the Roman Republic: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 1 edit by JimnyNewtron (talk) to last revision by Einsof |

|||

| (524 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Governing and advisory assembly of the aristocracy}} |

|||

The '''Roman Senate''' ([[Latin]]: ''Senatus'') was the main governing council of both the [[Roman Republic]], which started in [[509 BC]], and the [[Roman Empire]]. Although the [[West Roman Empire]] ended in the [[5th century CE]] (in [[476]]), the Roman Senate continued to meet until the latter part of the [[6th century CE]]. The word ''Senatus'' is derived from the Latin word ''senex'', meaning ''old man'' or ''elder''; thus, the ''Senate'' is, by etymology, the ''[[Council of Elders]]''. The senate was one of the three branches of government in the [[constitution of the Roman Republic]]. |

|||

[[File:Cicero Denounces Catiline in the Roman Senate by Cesare Maccari.png|thumb|right|upright=1.35|Representation of a sitting of the Roman Senate: [[Cicero]] attacks [[Catiline]], from a 19th-century fresco]] |

|||

{{Roman government}} |

|||

The '''Senate''' was the governing and advisory assembly of the aristocracy in the ancient [[Roman Republic]]. It was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the [[Roman consul|consuls]], and later by the [[Roman censor|censors]], which were appointed by the aristocratic [[Centuriate Assembly]]. After a [[Roman magistrate]] served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic appointment to the Senate. According to the Greek historian [[Polybius]], the principal source on the [[Constitution of the Roman Republic]], the [[Roman Senate]] was the predominant branch of government. Polybius noted that it was the ''[[Roman consul|consuls]]'' (the highest-ranking of the regular magistrates) who led the armies and the civil government in Rome, and it was the ''[[Roman assemblies]]'' which had the ultimate authority over elections, legislation, and criminal trials. However, since the Senate controlled money, administration, and the details of foreign policy, it had the most control over day-to-day life. The power and authority of the Senate derived from precedent, the high caliber and prestige of the senators, and the Senate's unbroken lineage, which dated back to the founding of the Republic in 509 BC. It developed from the [[Senate of the Roman Kingdom]], and became the [[Senate of the Roman Empire]]. |

|||

Originally the chief magistrates, the ''[[Roman consul|consul]]s'', appointed all new senators. They also had the power to remove individuals from the Senate. Around the year 318 BC, the "[[Ovinian Plebiscite]]" (''plebiscitum Ovinium'') gave this power to another Roman magistrate, the ''[[Roman censor|censor]]'', who retained this power until the end of the Roman Republic. This law also required the censors to appoint any newly elected magistrate to the Senate. Thus, after this point in time, election to magisterial office resulted in automatic Senate membership. The appointment was for life, although the censor could impeach any senator. |

|||

== History == |

|||

this is the jam for all the fellas, hmmblablabla hooooooooooooooooooooooo. Let me get, to the point.. If you want, to destroy my sweater..... pull this thread, as I walk awayyyy, AS I WALK AWAAAAYYYY! MR.D is the man!!! |

|||

Tradition held that the Senate was first established by [[Romulus and Remus| Romulus]], the mythical founder of Rome, as an advisory council consisting of the 100 heads of families, called ''Patres'' ("Fathers"). Later, when at the start of the [[Roman Republic|Republic]], [[Lucius Junius Brutus]] increased the number of Senators to three hundred (according to legend), they were also called ''Conscripti'' ("Conscripted Men"), because Brutus had conscripted them. From then on, the members of the Senate were addressed as "''Patres et Conscripti''", which was gradually run together as "''Patres Conscripti''" ("Conscript Fathers"). |

|||

The Senate directed the magistrates, especially the consuls, in their prosecution of military conflicts. The Senate also had an enormous degree of power over the civil government in Rome. This was especially the case with regard to its management of state finances, as only it could authorize the disbursal of public monies from the treasury. In addition, the Senate passed decrees called ''[[Senatus consultum|senatus consulta]]'', which were official "advice" from the Senate to a magistrate. While technically these decrees did not have to be obeyed, in practice, they usually were. During an emergency, the Senate (and only the Senate) could authorize the appointment of a ''[[Roman dictator|dictator]]''. The last ordinary dictator, however, was appointed in 202 BC. After 202 BC, the Senate responded to emergencies by passing the ''[[senatus consultum ultimum]]'' ("Ultimate Decree of the Senate"), which suspended civil government and declared something analogous to martial law. |

|||

The Roman population was divided into two classes: the Senate and the People (as seen in the famous [[abbreviation]] for "Senatus Populusque Romanus", [[SPQR]]). The People consisted of all Roman citizens who were not members of the Senate. Domestic power was vested in the Roman People, through the Centuriate Assembly (''[[Comitia Centuriata]]''), the Tribal Assembly (''[[Comitia Tributa]]'') and the Plebeian Council (''[[Concilium Plebis]]''). The two Assemblies passed new laws, as did the Council, which also elected Rome's [[magistrate]]s. The Senate proposed new legislation to the Assemblies and the Plebeian Council, which then voted on it without debate. The Assemblies and Plebeian Council could not propose legislation of their own. The Senate's dominance over Roman legislative matters is clear. |

|||

==Institution== |

|||

[[image:Curia Iulia.JPG|thumb|220px|left|The [[Curia Julia]] in the [[Roman Forum]], the seat of the Roman Senate.]] |

|||

[[File:Constitution of Rome.jpg|thumb|none|upright=1.8|Chart showing the checks and balances of the Constitution of the Roman Republic]] |

|||

==Venue and ethical standards== |

|||

The rules and procedures of the [[Roman Senate]] were both complex and ancient. Many of these rules and procedures originated in the early years of the Republic, and were upheld over the centuries under the principle of ''[[mos maiorum]]'' ("customs of the ancestors"). While Senate meetings could take place either inside or outside of the formal boundary of the city (the ''[[pomerium]]''), no meeting could take place more than a mile outside of the ''pomerium''.<ref name="Byrd, 34">Byrd, 34</ref> Senate meetings might take place outside of the formal boundary of the city for several reasons. For example, the Senate might wish to meet with an individual, such as a foreign ambassador, whom they did not wish to allow inside the city.<ref name="Lintott, 73">Lintott, 73</ref> |

|||

At the beginning of the year, the first Senate meeting always took place at the [[Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus|Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus]]. Other venues could include the [[Fides (mythology)|Temple of Fides]] or the [[Temple of Concord]],<ref name="Lintott, 72">Lintott, 72</ref> or, if the meeting was outside of the formal boundary of the city, at the [[Temple of Apollo Sosianus|Temple of Apollo]] or (if a war meeting) at the [[Temple of Bellona (Rome)|Temple of Bellona]]. In addition, the Senate operated while under various religious restrictions. For example, before any meeting could begin, a sacrifice to the gods was made, and a search for divine omens (the ''auspices'') was taken. The auspices were taken in order to determine whether that particular Senate meeting held favor with the gods.<ref name="Lintott, 72" /> The Senate was only allowed to meet in a building of religious significance, such as the [[Curia Hostilia]].<ref name="Lintott, 72" /> |

|||

The Senate held considerable clout (''auctoritas'') in Roman politics. It was the official body that sent and received ambassadors, and it appointed officials to manage public lands, including the provincial governors. It conducted wars and it also appropriated public funds. It was the Senate that authorized the city's chief magistrates, the [[consul]]s, to nominate a [[Roman dictator|dictator]] in a state of emergency. In the late Republic, the Senate chose to avoid setting up dictatorships by resorting to the so-called ''[[senatus consultum ultimum]]'', which declared martial law and empowered the consuls to "take care that the Republic should come to no harm". |

|||

The ethical requirements of senators were significant. Senators could not engage in banking or any form of public contract without legal approval. They could not own a ship that was large enough to participate in foreign commerce without legal approval,<ref name="Byrd, 34" /> and they could not leave Italy without permission from the Senate. In addition, since they were not paid, individuals usually sought to become a senator only if they were independently wealthy.<ref name="Byrd, 36">Byrd, 36</ref> |

|||

Like the ''Comitia Centuriata'' and the ''Comitia Tributa'', but unlike the ''Concilium Plebis'', the Senate operated under certain religious restrictions. It could only meet in a consecrated temple, which was usually the [[Curia Hostilia]], although the ceremonies of New Year's Day were in the temple of [[Jupiter Optimus Maximus]] and war meetings were held in the temple of [[Enyo| Bellona]]. Its sessions could only proceed after an invocation prayer, a sacrificial offering and the auspices were made. The Senate could only meet between sunrise and sunset, and could not meet while any of the assemblies were in session. |

|||

The ''[[Roman censor|censors]]'' were the magistrates who enforced the ethical standards of the Senate. Whenever a censor punished a senator, they had to allege some specific failing. Possible reasons for punishing a member included corruption, abuse of capital punishment, or the disregard of a colleague's veto, constitutional precedent, or the auspices. Senators who failed to obey various laws could also be punished. While punishment could include impeachment (expulsion) from the Senate, often a punishment was less severe than outright expulsion.<ref name="Lintott, 70">Lintott, 70</ref> While the standard was high for expelling a member from the Senate, it was easier to deny a citizen the right to join the Senate. Various moral failings could result in one not being allowed to join the Senate, including bankruptcy, prostitution, or a prior history of having been a gladiator. One law (the ''[[Lex Acilia repetundarum|Lex repetundarum]]'' of 123 BC) made it illegal for a citizen to become a senator if they had been convicted of a criminal offense.<ref name="Lintott, 70" /> Many of these laws were enacted in the last century of the Republic, as public corruption began reaching unprecedented levels.<ref name="Lintott, 70" /> |

|||

== Membership == |

|||

==Debates== |

|||

[[Image:Maccari-Cicero.jpg|thumb|300px|Representation of a sitting of the Roman Senate: [[Cicero]] attacks [[Catilina]], from a 19th century fresco]] |

|||

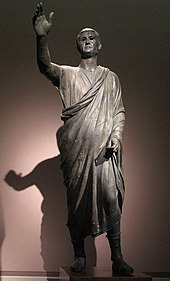

[[File:L'Arringatore.jpg|thumb|upright|''[[The Orator]]'', c. 100 BC, an [[Etruscan art|Etrusco]]-[[Roman sculpture|Roman]] [[bronze sculpture]] depicting Aule Metele (Latin: Aulus Metellus), an [[Etruscan civilization|Etruscan]] man of Roman senatorial rank, engaging in [[rhetoric]]. He wears [[senatorial shoes]] and a ''[[toga praetexta]]'' of the "skimpy" ({{lang|la|exigua}}) Republican type.<ref>Ceccarelli, L., in Bell, S., and Carpino, A., A, (Editors) ''A Companion to the Etruscans'' (Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World), Blackwell Publishing, 2016, p. 33</ref> The statue features an inscription in the [[Etruscan alphabet]]]] |

|||

[[File:Togatus Barberini 2392.PNG|thumb|upright|The so-called "[[Togatus Barberini]]", a statue depicting a [[Roman senator]] holding the ''[[Roman funerals and burial#Funerary art|imagines]]'' ([[effigies]]) of deceased ancestors in his hands; marble, late 1st century BC; head (not belonging): mid 1st century BC.]] |

|||

Meetings usually began at dawn, although occasionally certain events (such as festivals) might delay the beginning of a meeting. A magistrate who wished to summon the Senate had to issue a compulsory order (a ''cogere''), and senators could be punished if they failed to appear without reasonable cause. In 44 BC for example, consul [[Mark Antony]] threatened to demolish the house of the former consul [[Cicero]] for this very reason.<ref name="Lintott, 75">Lintott, 75</ref> The Senate meetings were technically public<ref name="Byrd, 34" /> because the doors were usually left open, which allowed people to look in, but only senators could speak. The Senate was directed by a presiding magistrate, who was usually either a ''[[Roman consul|consul]]'' (the highest-ranking magistrate) or, if the consul was unavailable, a ''[[Praetor]]'' (the second-highest ranking magistrate), usually the [[urban praetor]].<ref name="Byrd, 42">Byrd, 42</ref> By the late Republic, another type of magistrate, a ''[[Plebeian Tribune|plebeian tribune]]'', would sometimes preside.<ref name="Byrd, 34" /> |

|||

While in session, the Senate had the power to act on its own, and even against the will of the presiding magistrate if it wished. The presiding magistrate began each meeting with a speech (the ''verba fecit''),<ref name="Lintott, 78">Lintott, 78</ref> which was usually brief, but was sometimes a lengthy oration. The presiding magistrate would then begin a discussion by referring an issue to the senators, who would discuss the issue, one at a time, by order of seniority, with the first to speak, the most senior senator, known as the ''[[princeps senatus]]'' (leader of the Senate),<ref name="Byrd, 34" /> who was then followed by ex-consuls (''consulares''), and then the praetors and ex-praetors (''praetorii''). This continued, until the most junior senators had spoken.<ref name="Byrd, 34" /> Senators who had held magisterial office always spoke before those who had not, and if a ''[[Patrician (ancient Rome)|patrician]]'' was of equal seniority as a ''[[plebeian]]'', the patrician would always speak first.<ref name="Abbott, 228">Abbott, 228</ref> |

|||

The Senate had around 300 members in the middle and late Republic. Customarily, all popularly-elected magistrates — [[quaestor]]s, [[aedile]]s (both ''curulis'' and ''plebis''), [[praetor]]s, and [[consul]]s — were admitted to the Senate for life, though the inclusion of tribunes in the senate varied historically. Senators who had not been elected as magistrates were called ''senatores pedarii'' and were not permitted to speak. Their number was increased dramatically by Sulla, and around half (49.5%) of the pedarii from 78-49 BC were ''homines novi'' ("new men"), that is, those whose families had never attained higher magistracy. Outside the'' pedarii'', the number of ''homines novi'' was lower, with about 33% of tribunes, 29% of aediles, 22% of praetors, and only 1% of consuls being true ''novi'' (see E. S. Gruen, 1974, ''The Last Generation of the Roman Republic'', for a full breakdown on the family background of senators from 78-49 BC) . |

|||

A senator could make a brief statement, discuss the matter in detail, or talk about an unrelated topic. All senators had to speak before a vote could be held, and since all meetings had to end by nightfall,<ref name="Byrd, 44">Byrd, 44</ref> a senator could talk a proposal to death (a [[filibuster]] or ''diem consumere'') if they could keep the debate going until nightfall.<ref name="Lintott, 78" /> It is known, for example, that the senator [[Cato the Younger]] once filibustered in an attempt to prevent the Senate from granting [[Julius Caesar]] a law that would have given land to the veterans of [[Pompey]].<ref name="Lintott, 78" /><ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.bookrags.com/biography/cato-the-younger/ |title=Cato, the Younger Biography | Encyclopedia of World Biography Biography |publisher=Bookrags.com |access-date=2008-09-19}}</ref> |

|||

Membership to the Senate was largely determined by popular election after Sulla's enlargement, membership in the Senate could be stripped by the [[Censor (ancient Rome)|censor]]s if a Senator had been found guilty of disregard of the ''[[Mos maiorum|mores maiorum]]'' (public morals, literally: the ways of the forefathers), e.g. corruption, disregard of a colleague's veto, abuse of capital punishment, severe domestic violence, improper treatment of ''clients'' or slaves, and bankrupts or adultery, or if [[auspice]]s demanded to. |

|||

==Delaying and obstructive tactics== |

|||

== Late Republican Senate == |

|||

Senators had several ways in which they could influence (or frustrate) a presiding magistrate. When a presiding magistrate was proposing a motion, for example, the senators could call "consult" (''consule''), which required the magistrate to ask for the opinions of the senators. Any senator could demand a [[quorum call]] (with the cry of ''numera''), which required a count of the senators present. Like modern quorum calls, this was usually a delaying tactic. Senators could also demand that a motion be divided into smaller motions. Acts such as applause, booing, or heckling often played a major role in a debate, and, in part because all senators had an absolute right to free speech, any senator could respond at any point if he was attacked personally.<ref name="Byrd, 34" /> Once debates were underway, they were usually difficult for the presiding magistrate to control. The presiding magistrate typically only regained some control once the debating had ended, and a vote was about to be taken.<ref name="Lintott, 82">Lintott, 82</ref> |

|||

In the later years of the Republic, attempts were made by the aristocracy to limit the increasing level of chaos associated with the obstructive tendencies and democratic impulses of some of the senators. Laws were enacted to prevent the inclusion of extraneous material in bills before the Senate. Other laws were enacted to outlaw the so-called [[omnibus bill]]s,<ref name="Byrd, 112">Byrd, 112</ref> which are bills, usually enacted by a single vote, that contain a large volume of often unrelated material.<ref name="Byrd, 112" /> |

|||

In the late Republic, an archconservative faction emerged, led in turn by [[Marcus Aemilius Scaurus]], [[Quintus Lutatius Catulus]], [[Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus]] and [[Cato the Younger]], whom Cicero called the ''boni'' ("The Good Men") or ''[[Optimates]]''. The Late Republic was characterised by the social tensions between the broad factions of the ''Optimates'' and the newly wealthy ''[[Populares]]''. This struggle became increasingly expressed by domestic fury, violence and fierce civil strife after the formation of the triumvirate of Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus. Examples of ''Optimates'' include [[Lucius Cornelius Sulla]] and [[Pompey the Great]], whereas [[Gaius Marius]], [[Lucius Cornelius Cinna]] and [[Julius Caesar]] were ''Populares''. The labels Populares and Optimates were not, however, as fixed as sometimes assumed, and politicians often changed factions to support specific bills or personalities. |

|||

Laws were also enacted to strengthen the requirement that three days pass between the proposal of a bill, and the vote on that bill.<ref name="Byrd, 112" /> During his term as [[Roman dictator|dictator]], Julius Caesar enacted laws that required the publication of Senate resolutions. This publication, called the ''[[Acta Senatus|acta diurna]]'', or "daily proceedings", was meant to increase transparency and minimize the potential for abuse.<ref name="Byrd, 133">Byrd, 133</ref> This publication was posted in the [[Roman Forum]], and then sent by messengers throughout the provinces.<ref name="Byrd, 133" /> |

|||

== Hierarchy == |

|||

==Votes and the Tribune's vote== |

|||

The [[consul]]s alternated monthly as president of the Senate, while the ''[[princeps senatus]]'' functioned as leader of the house, the senatorial office assumed by the Emperors during the Imperial Period. If both [[consul]]s were absent (usually because of a war), the senior magistrate, most often the [[praetor |Praetor Urbanus]], would act as the president. Originally, it was the president's duty to lay business before the Senate, either his own proposition or a topic by which he would solicit the senators for their propositions, but this soon became the domain of the ''princeps''. Among the senators with speaking rights a rigid order defined who could speak when, with a patrician always preceding a plebeian of equal rank, and the ''princeps'' speaking first. |

|||

When it was time to call a vote, the presiding magistrate could bring up whatever proposals (in whatever order) he wished, and every vote was between a proposal and its negative.<ref name="Lintott, 83">Lintott, 83</ref> Quorums were required for votes to be held, and it is known that in 67 BC the size of a quorum was set at 200 senators (by the ''[[lex Cornelia de privilegiis]]''). At any point before a motion passed, the proposed motion could be vetoed. Usually, vetoes were handed down by plebeian tribunes. If the Senate proposed a bill that the ''[[Plebeian Tribune|plebeian tribune]]'' (the magistrate who was the chief representative{{Clarify|date=October 2009}} of the people) did not agree with, he issued a [[veto]], which was backed by the promise to literally "interpose the sacrosanctity of his person" (or ''intercessio'') if the Senate did not comply. If the Senate did not comply, he could physically prevent the Senate from acting, and any resistance could be criminally prosecuted as constituting a violation of his sacrosanctity. If the vetoed motion was proposed the next day, and the plebeian tribune who had vetoed it the day before was not present to interpose himself, the motion could be passed. In general, the plebeian tribune had to physically be present at the Senate meeting, otherwise his physical threat of interposing his person had no meaning. Ultimately, the plebeian tribune's veto was based in a promise of physical force.<ref name="Lintott, 83" /> |

|||

The ''consulares'' were among the most influential members of the Senate. The ''consulares'' were those senators who had held the position of [[consul]]. Since only two [[consul]]s were elected yearly with the minimum age of 40 for [[patrician]]s and 42 for [[plebeian]]s, there were unlikely to be more than 40 ''consulares'' in the Senate at any given time. |

|||

Once a vote occurred, and a measure passed, he could do nothing, since his promise to physically interpose his person against the senators was now meaningless. In addition, during a couple of instances between the end of the [[Second Punic War]] in 201 BC and the beginning of the [[Social War (91–88 BC)|Social War]] in 91 BC, although they had no legal power to do so, several Consuls were known to have vetoed acts of the Senate. Ultimately, if there was no veto, and the matter was of minor importance, it could be voted on by a voice vote or by a show of hands. If there was no veto, and the matter was of a significant nature, there was usually a physical division of the house, where senators voted by taking a place on either side of the chamber.<ref name="Byrd, 34" /> |

|||

== Notable practices == |

|||

Any motion that had the support of the Senate but was vetoed was recorded in the annals as a ''senatus auctoritas'', while any motion that was passed and not vetoed was recorded as a ''senatus consultum''. After the vote, each ''[[senatus consultum]]'' and each ''[[senatus auctoritas]]'' was transcribed into a final document by the presiding magistrate. This document included the name of the presiding magistrate, the place of the assembly, the dates involved, the number of senators who were present at time the motion was passed, the names of witnesses to the drafting of the motion, and the substance of the act. In addition, if the motion was a ''senatus consultum'', a capital letter "C" was stamped on the document, to verify that the motion had been approved by the Senate.<ref name="Lintott, 85">Lintott, 85</ref> |

|||

There was no limit on debate, and the practice of talking out debate (which is now sometimes called a [[filibuster]]) was a favoured trick (a practice which continues to be accepted in [[Canada]] and the [[United States]] today). Votes could be taken by voice vote or show of hands in unimportant matters, but important or formal motions were decided by [[division of the house]]. A [[quorum]] to do business was necessary, but it is not known how many senators constituted a quorum. The Senate was divided into decuries (groups of ten), each led by a patrician (thus requiring that there would be at least 30 patrician senators at any given time). |

|||

The document was then deposited in the temple that housed the Treasury (the ''[[aerarium]]'').<ref name="Byrd, 44" /> While a ''senatus auctoritas'' (vetoed Senate motion) had no legal value, it did serve to show the opinion of the Senate. If a ''senatus consultum'' conflicted with a law (''lex'') that was passed by a [[Roman assemblies|Roman Assembly]], the law overrode the ''senatus consultum'', because the ''senatus consultum'' had its authority based in precedent, and not in law. A ''senatus consultum'', however, could serve to interpret a law.<ref name="Abbott, 233">Abbott, 233</ref> |

|||

== Style of dress == |

|||

==See also== |

|||

All senators were entitled to wear a senatorial ring (originally made of iron, but later gold; old patrician families like the Julii Caesares continued to wear iron rings to the end of the Republic) and a ''tunica clava'', a white tunic with a broad stripe of [[Purple|Tyrian purple]] 13 cm (5.12 in) wide (''latus clavus'') on the right shoulder. A ''senator pedarius'' wore a white ''toga virilis'' (also called a ''toga pura'') without decoration excluding those explained above, whereas a senator who had held a curule magistracy was entitled to wear the ''toga praetexta'', a white toga with a broad Tyrian purple border. Similarly, all senators wore closed [[maroon (color)|maroon]] leather shoes, but senators who had held curule magistracies added a crescent-shaped buckle. |

|||

{{columns-list |colwidth=15em| |

|||

== The Equestrian class == |

|||

* [[Byzantine Senate]] |

|||

Until 123 BC, all senators were also [[Equestrian (Roman)|equestrians]], frequently called "knights" in English works. That year, [[Gaius Sempronius Gracchus]] legislated the separation of the two classes, and established the latter as the ''Ordo Equester'' ("Equestrian Order"). These equestrians were not restricted in their business ventures and were a wealthy and powerful force in Roman politics. Sons of senators and other non-senatorial members of senatorial families continued to be classified as equestrians and were entitled to wear togas with narrow purple stripes 7.5 centimeters wide as a reminder of their senatorial origins. |

|||

* [[Commune of Rome]] (1144 onward) |

|||

* [[Roman Law]] |

|||

* [[Centuria]] |

|||

* [[Curia]] |

|||

* [[Quaestor]] |

|||

* [[Aedile]] |

|||

* [[Plebeian Council]] |

|||

* [[Cursus honorum]] |

|||

* [[Pontifex Maximus]] |

|||

* [[Roman senate]] |

|||

* [[Interrex]] |

|||

* [[Procurator (ancient Rome)]] |

|||

* [[Acta Senatus]] |

|||

}} |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

== Decline of the Senate (1st century BC – 6th century AD) == |

|||

{{reflist|30em}} |

|||

==References== |

|||

[[Julius Caesar]] introduced ''viri clarissimi'' (singular ''vir clarissimus'', literally very distinguished man), with equestrians becoming ''viri egregii'' (vir egregius), "outstanding man". During the [[Principate]] and the [[Dominate]], the Senate gradually lost its powers, including the right to confer imperial power.<ref>At his accession in [[282]], the emperor [[Carus]] informed the Senate of the fact that he had been acclaimed emperor by his soldiers and hence possessed full imperial authority. His example of disregarding the role of the Senate in the confirmation of new emperors was followed by [[Diocletian]]. (W.G. Sinnigen and A.E.R. Boak, ''A history of Rome to A.D. 565'' (New York-London 1977), p. 399)</ref> While supreme power was in fact vested in the Imperator, the Senate remained a very powerful force as it saw to many of the more mundane aspects of governing. New senators were chosen by the Emperor based on wealth, administrative skill and ties to the ruler. New senators were given vast amounts of land, if they did not already possess them. Much of the surviving literature from the imperial period is written by senators, thus demonstrating their strong cultural influence. The institution survived the end of the [[Western Roman Empire|Empire in the West]], even enjoying a modest revival as imperial power was reduced to a government of Italy only. The senatorial class was severely affected by the [[Gothic_War_%28535%E2%80%93554%29|Gothic wars]]. The Senate's last recorded acts are the dispatch of two ambassadors to the Imperial court of [[Tiberius II Constantine]] at [[Constantinople]] in [[578]] and [[580]]. |

|||

*{{Cite book|author=Abbott, Frank Frost|year=1901|title=A History and Description of Roman Political Institutions|publisher=Elibron Classics|isbn=0-543-92749-0}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|author=Byrd, Robert|year=1995|title=The Senate of the Roman Republic|publisher=US Government Printing Office Senate Document 103–23|isbn=0-16-058996-7}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|author=Cicero, Marcus Tullius|year=1841|title=The Political Works of Marcus Tullius Cicero: Comprising his Treatise on the Commonwealth; and his Treatise on the Laws|edition=Translated from the original, with Dissertations and Notes in Two Volumes By Francis Barham, Esq|location=London|publisher=Edmund Spettigue|volume=1}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|author=Holland, Tom|year=2005|title=Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic|publisher=Random House Books|isbn=1-4000-7897-0|url=https://archive.org/details/rubiconlastyears00holl}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|author=Lintott, Andrew|year=1999|title=The Constitution of the Roman Republic|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=0-19-926108-3}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|author=Polybius|year=1823|title=The General History of Polybius: Translated from the Greek|publisher=Oxford: Printed by W. Baxter|edition=Fifth|volume=2}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|author=Taylor, Lily Ross|year=1966|title=Roman Voting Assemblies: From the Hannibalic War to the Dictatorship of Caesar|publisher=The University of Michigan Press|isbn=0-472-08125-X|url=https://archive.org/details/romanvotingassem00tayl}} |

|||

* {{cite journal|year=1969|volume=100|pages=529–582|doi=10.2307/2935928|title=Seating Space in the Roman Senate and the Senatores Pedarii|author=Taylor, Lily Ross|journal=Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association|author2=Scott, Russell T|publisher=The Johns Hopkins University Press|jstor=2935928|ref=Taylor}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

== Eastern Roman Senate == |

|||

{{refbegin}} |

|||

* Cambridge Ancient History, Volumes 9–13. |

|||

{{main|Byzantine Senate}} |

|||

* Cameron, A. ''The Later Roman Empire'', (Fontana Press, 1993). |

|||

* Crawford, M. ''The Roman Republic'', (Fontana Press, 1978). |

|||

* Gruen, E. S. "The Last Generation of the Roman Republic" (U California Press, 1974) |

|||

* Ihne, Wilhelm. ''Researches Into the History of the Roman Constitution''. William Pickering. 1853. |

|||

* Johnston, Harold Whetstone. ''Orations and Letters of Cicero: With Historical Introduction, An Outline of the Roman Constitution, Notes, Vocabulary and Index''. Scott, Foresman and Company. 1891. |

|||

* Millar, F. ''The Emperor in the Roman World'', (Duckworth, 1977, 1992). |

|||

* Mommsen, Theodor. ''Roman Constitutional Law''. 1871–1888 |

|||

* [[Polybius]]. ''The Histories'' |

|||

* Tighe, Ambrose. ''The Development of the Roman Constitution''. D. Apple & Co. 1886. |

|||

* Von Fritz, Kurt. ''The Theory of the Mixed Constitution in Antiquity''. Columbia University Press, New York. 1975. |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

Meanwhile a separate Senate had been established by [[Constantine I]] in Constantinople, which survived, in name if not importance, for centuries afterwards. |

|||

==External links== |

|||

== Revival in the Middle Ages == |

|||

* [http://oll.libertyfund.org/?option=com_staticxt&staticfile=show.php%3Ftitle=546&chapter=83299&layout=html&Itemid=27 Cicero's De Re Publica, Book Two] |

|||

* [http://www.fordham.edu/HALSALL/ANCIENT/polybius6.html Rome at the End of the Punic Wars: An Analysis of the Roman Government; by Polybius] |

|||

{{Roman Constitution|state=collapsed}} |

|||

In the 12th century a commune was briefly established in Rome in an effort to reestablish the old Roman Republic. In 1145 the revolutionaries set up a Senate on the lines of the ancient one. See [[Commune of Rome]]. |

|||

{{Ancient Rome topics|state=collapsed}} |

|||

{{good article}} |

|||

Although the republican movement was defeated in 1155 by [[Pope Hadrian IV]], the Roman city council has been called "Senate" since that time, and this old tradition has survived to the present day. The seat of the Senate of the ''comune di Roma'' is the [[Palazzo Senatorio]] on the [[Campidoglio]]. |

|||

== Original Roman Senate Building == |

|||

An original building in which the Roman Senate met, a stone structure with a double slanted tiled roof, still exists in Rome. This building is not the same one where Cicero, for example, delivered his famous orations against Catiline, but one that was constructed after the original was burned by a mob that supported the populist agitator [[Publius Clodius Pulcher]] in 52 BC. |

|||

== Footnotes == |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

== References == |

|||

* ''The Histories'' by [[Polybius]] |

|||

* Cambridge Ancient History, Volumes 9–13. |

|||

* A. Cameron, ''The Later Roman Empire'', (Fontana Press, 1993). |

|||

* M. Crawford, ''The Roman Republic'', (Fontana Press, 1978). |

|||

* E. S. Gruen, "The Last Generation of the Roman Republic" (U California Press, 1974) |

|||

* F. Millar, ''The Emperor in the Roman World'', (Duckworth, 1977, 1992). |

|||

* A. Lintott, "The Constitution of the Roman Republic" (Oxford University Press, 1999) |

|||

== See also == |

|||

* [[Senate]] |

|||

* [[Constitution of the Roman Republic]] |

|||

* [[cursus honorum]] |

|||

* [[Byzantine Senate]] |

|||

* [[consul]] |

|||

* [[praetor]] |

|||

* [[Censor (ancient Rome)|censor]] |

|||

* [[tribune]] |

|||

* [[aedile]] |

|||

* [[quaestor]] |

|||

* [[Pontifex Maximus]] |

|||

* [[Princeps senatus]] |

|||

* [[Interrex]] |

|||

* [[procurator]] |

|||

* [[Roman dictator]] |

|||

* [[Master of the horse]] |

|||

* [[Acta Senatus]] |

|||

[[Category:Government of the Roman Republic]] |

|||

[[Category:Historical legislatures]] |

[[Category:Historical legislatures]] |

||

[[Category:Roman Senate]] |

|||

[[bs:Rimski senat]] |

|||

[[ca:Senat romà]] |

|||

[[cs:Římský senát]] |

|||

[[cy:Senedd Rhufain]] |

|||

[[da:Det romerske Senat]] |

|||

[[de:Römischer Senat]] |

|||

[[el:Σύγκλητος]] |

|||

[[es:Senado romano]] |

|||

[[eu:Erromako Senatua]] |

|||

[[fr:Sénat romain]] |

|||

[[gl:Senado romano]] |

|||

[[ko:원로원]] |

|||

[[is:Rómverska öldungaráðið]] |

|||

[[it:Senato romano]] |

|||

[[he:הסנאט הרומי]] |

|||

[[ka:რომის სენატი]] |

|||

[[la:Senatus Romanus]] |

|||

[[lt:Romos senatas]] |

|||

[[hu:Senatus]] |

|||

[[nl:Senaat (Rome)]] |

|||

[[ja:元老院 (ローマ)]] |

|||

[[no:Det romerske senatet]] |

|||

[[pl:Senat rzymski]] |

|||

[[pt:Senado romano]] |

|||

[[ro:Senatul roman]] |

|||

[[ru:Сенат (Древний Рим)]] |

|||

[[sr:Римски сенат]] |

|||

[[sh:Rimski senat]] |

|||

[[fi:Rooman senaatti]] |

|||

[[sv:Romerska senaten]] |

|||

[[zh:羅馬元老院]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 11:08, 11 May 2024

|

|---|

| Periods |

|

| Constitution |

| Political institutions |

| Assemblies |

| Ordinary magistrates |

| Extraordinary magistrates |

| Public law |

| Senatus consultum ultimum |

| Titles and honours |

The Senate was the governing and advisory assembly of the aristocracy in the ancient Roman Republic. It was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors, which were appointed by the aristocratic Centuriate Assembly. After a Roman magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic appointment to the Senate. According to the Greek historian Polybius, the principal source on the Constitution of the Roman Republic, the Roman Senate was the predominant branch of government. Polybius noted that it was the consuls (the highest-ranking of the regular magistrates) who led the armies and the civil government in Rome, and it was the Roman assemblies which had the ultimate authority over elections, legislation, and criminal trials. However, since the Senate controlled money, administration, and the details of foreign policy, it had the most control over day-to-day life. The power and authority of the Senate derived from precedent, the high caliber and prestige of the senators, and the Senate's unbroken lineage, which dated back to the founding of the Republic in 509 BC. It developed from the Senate of the Roman Kingdom, and became the Senate of the Roman Empire.

Originally the chief magistrates, the consuls, appointed all new senators. They also had the power to remove individuals from the Senate. Around the year 318 BC, the "Ovinian Plebiscite" (plebiscitum Ovinium) gave this power to another Roman magistrate, the censor, who retained this power until the end of the Roman Republic. This law also required the censors to appoint any newly elected magistrate to the Senate. Thus, after this point in time, election to magisterial office resulted in automatic Senate membership. The appointment was for life, although the censor could impeach any senator.

The Senate directed the magistrates, especially the consuls, in their prosecution of military conflicts. The Senate also had an enormous degree of power over the civil government in Rome. This was especially the case with regard to its management of state finances, as only it could authorize the disbursal of public monies from the treasury. In addition, the Senate passed decrees called senatus consulta, which were official "advice" from the Senate to a magistrate. While technically these decrees did not have to be obeyed, in practice, they usually were. During an emergency, the Senate (and only the Senate) could authorize the appointment of a dictator. The last ordinary dictator, however, was appointed in 202 BC. After 202 BC, the Senate responded to emergencies by passing the senatus consultum ultimum ("Ultimate Decree of the Senate"), which suspended civil government and declared something analogous to martial law.

Institution[edit]

Venue and ethical standards[edit]

The rules and procedures of the Roman Senate were both complex and ancient. Many of these rules and procedures originated in the early years of the Republic, and were upheld over the centuries under the principle of mos maiorum ("customs of the ancestors"). While Senate meetings could take place either inside or outside of the formal boundary of the city (the pomerium), no meeting could take place more than a mile outside of the pomerium.[1] Senate meetings might take place outside of the formal boundary of the city for several reasons. For example, the Senate might wish to meet with an individual, such as a foreign ambassador, whom they did not wish to allow inside the city.[2]

At the beginning of the year, the first Senate meeting always took place at the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus. Other venues could include the Temple of Fides or the Temple of Concord,[3] or, if the meeting was outside of the formal boundary of the city, at the Temple of Apollo or (if a war meeting) at the Temple of Bellona. In addition, the Senate operated while under various religious restrictions. For example, before any meeting could begin, a sacrifice to the gods was made, and a search for divine omens (the auspices) was taken. The auspices were taken in order to determine whether that particular Senate meeting held favor with the gods.[3] The Senate was only allowed to meet in a building of religious significance, such as the Curia Hostilia.[3]

The ethical requirements of senators were significant. Senators could not engage in banking or any form of public contract without legal approval. They could not own a ship that was large enough to participate in foreign commerce without legal approval,[1] and they could not leave Italy without permission from the Senate. In addition, since they were not paid, individuals usually sought to become a senator only if they were independently wealthy.[4]

The censors were the magistrates who enforced the ethical standards of the Senate. Whenever a censor punished a senator, they had to allege some specific failing. Possible reasons for punishing a member included corruption, abuse of capital punishment, or the disregard of a colleague's veto, constitutional precedent, or the auspices. Senators who failed to obey various laws could also be punished. While punishment could include impeachment (expulsion) from the Senate, often a punishment was less severe than outright expulsion.[5] While the standard was high for expelling a member from the Senate, it was easier to deny a citizen the right to join the Senate. Various moral failings could result in one not being allowed to join the Senate, including bankruptcy, prostitution, or a prior history of having been a gladiator. One law (the Lex repetundarum of 123 BC) made it illegal for a citizen to become a senator if they had been convicted of a criminal offense.[5] Many of these laws were enacted in the last century of the Republic, as public corruption began reaching unprecedented levels.[5]

Debates[edit]

Meetings usually began at dawn, although occasionally certain events (such as festivals) might delay the beginning of a meeting. A magistrate who wished to summon the Senate had to issue a compulsory order (a cogere), and senators could be punished if they failed to appear without reasonable cause. In 44 BC for example, consul Mark Antony threatened to demolish the house of the former consul Cicero for this very reason.[7] The Senate meetings were technically public[1] because the doors were usually left open, which allowed people to look in, but only senators could speak. The Senate was directed by a presiding magistrate, who was usually either a consul (the highest-ranking magistrate) or, if the consul was unavailable, a Praetor (the second-highest ranking magistrate), usually the urban praetor.[8] By the late Republic, another type of magistrate, a plebeian tribune, would sometimes preside.[1]

While in session, the Senate had the power to act on its own, and even against the will of the presiding magistrate if it wished. The presiding magistrate began each meeting with a speech (the verba fecit),[9] which was usually brief, but was sometimes a lengthy oration. The presiding magistrate would then begin a discussion by referring an issue to the senators, who would discuss the issue, one at a time, by order of seniority, with the first to speak, the most senior senator, known as the princeps senatus (leader of the Senate),[1] who was then followed by ex-consuls (consulares), and then the praetors and ex-praetors (praetorii). This continued, until the most junior senators had spoken.[1] Senators who had held magisterial office always spoke before those who had not, and if a patrician was of equal seniority as a plebeian, the patrician would always speak first.[10]

A senator could make a brief statement, discuss the matter in detail, or talk about an unrelated topic. All senators had to speak before a vote could be held, and since all meetings had to end by nightfall,[11] a senator could talk a proposal to death (a filibuster or diem consumere) if they could keep the debate going until nightfall.[9] It is known, for example, that the senator Cato the Younger once filibustered in an attempt to prevent the Senate from granting Julius Caesar a law that would have given land to the veterans of Pompey.[9][12]

Delaying and obstructive tactics[edit]

Senators had several ways in which they could influence (or frustrate) a presiding magistrate. When a presiding magistrate was proposing a motion, for example, the senators could call "consult" (consule), which required the magistrate to ask for the opinions of the senators. Any senator could demand a quorum call (with the cry of numera), which required a count of the senators present. Like modern quorum calls, this was usually a delaying tactic. Senators could also demand that a motion be divided into smaller motions. Acts such as applause, booing, or heckling often played a major role in a debate, and, in part because all senators had an absolute right to free speech, any senator could respond at any point if he was attacked personally.[1] Once debates were underway, they were usually difficult for the presiding magistrate to control. The presiding magistrate typically only regained some control once the debating had ended, and a vote was about to be taken.[13]

In the later years of the Republic, attempts were made by the aristocracy to limit the increasing level of chaos associated with the obstructive tendencies and democratic impulses of some of the senators. Laws were enacted to prevent the inclusion of extraneous material in bills before the Senate. Other laws were enacted to outlaw the so-called omnibus bills,[14] which are bills, usually enacted by a single vote, that contain a large volume of often unrelated material.[14]

Laws were also enacted to strengthen the requirement that three days pass between the proposal of a bill, and the vote on that bill.[14] During his term as dictator, Julius Caesar enacted laws that required the publication of Senate resolutions. This publication, called the acta diurna, or "daily proceedings", was meant to increase transparency and minimize the potential for abuse.[15] This publication was posted in the Roman Forum, and then sent by messengers throughout the provinces.[15]

Votes and the Tribune's vote[edit]

When it was time to call a vote, the presiding magistrate could bring up whatever proposals (in whatever order) he wished, and every vote was between a proposal and its negative.[16] Quorums were required for votes to be held, and it is known that in 67 BC the size of a quorum was set at 200 senators (by the lex Cornelia de privilegiis). At any point before a motion passed, the proposed motion could be vetoed. Usually, vetoes were handed down by plebeian tribunes. If the Senate proposed a bill that the plebeian tribune (the magistrate who was the chief representative[clarification needed] of the people) did not agree with, he issued a veto, which was backed by the promise to literally "interpose the sacrosanctity of his person" (or intercessio) if the Senate did not comply. If the Senate did not comply, he could physically prevent the Senate from acting, and any resistance could be criminally prosecuted as constituting a violation of his sacrosanctity. If the vetoed motion was proposed the next day, and the plebeian tribune who had vetoed it the day before was not present to interpose himself, the motion could be passed. In general, the plebeian tribune had to physically be present at the Senate meeting, otherwise his physical threat of interposing his person had no meaning. Ultimately, the plebeian tribune's veto was based in a promise of physical force.[16]

Once a vote occurred, and a measure passed, he could do nothing, since his promise to physically interpose his person against the senators was now meaningless. In addition, during a couple of instances between the end of the Second Punic War in 201 BC and the beginning of the Social War in 91 BC, although they had no legal power to do so, several Consuls were known to have vetoed acts of the Senate. Ultimately, if there was no veto, and the matter was of minor importance, it could be voted on by a voice vote or by a show of hands. If there was no veto, and the matter was of a significant nature, there was usually a physical division of the house, where senators voted by taking a place on either side of the chamber.[1]

Any motion that had the support of the Senate but was vetoed was recorded in the annals as a senatus auctoritas, while any motion that was passed and not vetoed was recorded as a senatus consultum. After the vote, each senatus consultum and each senatus auctoritas was transcribed into a final document by the presiding magistrate. This document included the name of the presiding magistrate, the place of the assembly, the dates involved, the number of senators who were present at time the motion was passed, the names of witnesses to the drafting of the motion, and the substance of the act. In addition, if the motion was a senatus consultum, a capital letter "C" was stamped on the document, to verify that the motion had been approved by the Senate.[17]

The document was then deposited in the temple that housed the Treasury (the aerarium).[11] While a senatus auctoritas (vetoed Senate motion) had no legal value, it did serve to show the opinion of the Senate. If a senatus consultum conflicted with a law (lex) that was passed by a Roman Assembly, the law overrode the senatus consultum, because the senatus consultum had its authority based in precedent, and not in law. A senatus consultum, however, could serve to interpret a law.[18]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Byrd, 34

- ^ Lintott, 73

- ^ a b c Lintott, 72

- ^ Byrd, 36

- ^ a b c Lintott, 70

- ^ Ceccarelli, L., in Bell, S., and Carpino, A., A, (Editors) A Companion to the Etruscans (Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World), Blackwell Publishing, 2016, p. 33

- ^ Lintott, 75

- ^ Byrd, 42

- ^ a b c Lintott, 78

- ^ Abbott, 228

- ^ a b Byrd, 44

- ^ Cato, the Younger Biography | Encyclopedia of World Biography Biography. Bookrags.com. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ^ Lintott, 82

- ^ a b c Byrd, 112

- ^ a b Byrd, 133

- ^ a b Lintott, 83

- ^ Lintott, 85

- ^ Abbott, 233

References[edit]

- Abbott, Frank Frost (1901). A History and Description of Roman Political Institutions. Elibron Classics. ISBN 0-543-92749-0.

- Byrd, Robert (1995). The Senate of the Roman Republic. US Government Printing Office Senate Document 103–23. ISBN 0-16-058996-7.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius (1841). The Political Works of Marcus Tullius Cicero: Comprising his Treatise on the Commonwealth; and his Treatise on the Laws. Vol. 1 (Translated from the original, with Dissertations and Notes in Two Volumes By Francis Barham, Esq ed.). London: Edmund Spettigue.

- Holland, Tom (2005). Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. Random House Books. ISBN 1-4000-7897-0.

- Lintott, Andrew (1999). The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926108-3.

- Polybius (1823). The General History of Polybius: Translated from the Greek. Vol. 2 (Fifth ed.). Oxford: Printed by W. Baxter.

- Taylor, Lily Ross (1966). Roman Voting Assemblies: From the Hannibalic War to the Dictatorship of Caesar. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08125-X.

- Taylor, Lily Ross; Scott, Russell T (1969). "Seating Space in the Roman Senate and the Senatores Pedarii". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 100. The Johns Hopkins University Press: 529–582. doi:10.2307/2935928. JSTOR 2935928.

Further reading[edit]

- Cambridge Ancient History, Volumes 9–13.

- Cameron, A. The Later Roman Empire, (Fontana Press, 1993).

- Crawford, M. The Roman Republic, (Fontana Press, 1978).

- Gruen, E. S. "The Last Generation of the Roman Republic" (U California Press, 1974)

- Ihne, Wilhelm. Researches Into the History of the Roman Constitution. William Pickering. 1853.

- Johnston, Harold Whetstone. Orations and Letters of Cicero: With Historical Introduction, An Outline of the Roman Constitution, Notes, Vocabulary and Index. Scott, Foresman and Company. 1891.

- Millar, F. The Emperor in the Roman World, (Duckworth, 1977, 1992).

- Mommsen, Theodor. Roman Constitutional Law. 1871–1888

- Polybius. The Histories

- Tighe, Ambrose. The Development of the Roman Constitution. D. Apple & Co. 1886.

- Von Fritz, Kurt. The Theory of the Mixed Constitution in Antiquity. Columbia University Press, New York. 1975.

External links[edit]

- Cicero's De Re Publica, Book Two

- Rome at the End of the Punic Wars: An Analysis of the Roman Government; by Polybius