Palestinians

A Palestinian family portrait from 1900 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 3,000,000 | |

| 1,318,000 | |

| 434,896 | |

| 405,425 | |

| 300,000 | |

| 70,245 | |

| Languages | |

| Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam (97%), Christianity (3%), others (<1%) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Arabs, Jews, Bedouins, and other Semitic peoples | |

Palestinian people (Arabic: الشعب الفلسطيني, ash-sha'ab il-filastini), Palestinians (Arabic: الفلسطينيين, al-filastiniyyin), or Palestinian Arabs (Arabic: العربي الفلسطيني, al-'arabi il-filastini) are terms used to refer to an Arabic-speaking people with family origins in Palestine.

The first widespread endonymic use of "Palestinian" to refer to the nationalist concept of a Palestinian people by the Arabs of Palestine began prior to the outbreak of World War I,[1] and the first demand for national independence was issued by the Syrian-Palestinian Congress on 21 September, 1921.[2] After the exodus of 1948, and even more so after the exodus of 1967, the term came to signify not only a place of origin, but the sense of a shared past and future in the form of a Palestinian nation-state.[1]

The total Palestinian population worldwide is estimated to be between 10 and 11 million people, over half of whom are stateless, lacking citizenship in any country.[3] Palestinians are predominantly Sunni Muslims, though there is a significant Christian minority as well as smaller religious communities.

Roughly half of all Palestinians continue to live in parts of the former British Mandate—an area today known as Israel, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem.[i] The other half, many of whom are refugees, live elsewhere in different places throughout the world. (See Palestinian diaspora.)

The Palestinian people as a whole are represented before the international community by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).[4] The Palestinian National Authority, created as a result of the Oslo Accords, is an interim administrative body nominally responsible for governance in Palestinian population centers in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Origins of Palestinian identity

Etymology

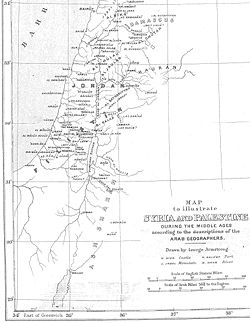

The Greek toponym Palaistinê (Παλαιστίνη), with which the Arabic Filastin (فلسطين) is cognate, first occurs in the work of the Ionian historian Herodotus, active in the middle of the 5th century BCE, where it denotes generally[5] the coastal land, between Phoenicia of Sidon, to Egypt!, as Herodotus describes the Fifth Satrapy of the Perthians "From the town of Posidium, which was founded by Amphilochus, son of Amphiaraus, on the border between Cilicia and Syria, as far as Egypt - omitting Arabian territory, which was free of tax, came 350 talents. This province contains the whole of Phoenicia and that part of Syria which is called Palestine, and Cyprus. This is the fifth Satrapy" (from Herodotus Book 3, 8th logos)[6]. In expressions where he employs it as an ethnonym, as when he speaks of the 'Syrians of Palestine'[6] it refers to a population distinct from the Phoenicians, and thus probably Philistines, though it may also cover several other tribes and ethnic groups present in the area, including the Jews.[7] The word bears comparison to a congeries of ethnonyms in Semitic languages, Ancient Egyptian Prst, Assyrian Palastu, and the Hebraic Plishtim, the latter term used in the Bible to signify the Philistines. The Romans divided Palestine into Palestina I and Palestina II untill 635 AD.

The Arabic word Filastin has been used to refer to the region since the earliest medieval Arab geographers adopted the Greek name. Filastini (فلسطيني), also derived from the Latinized Greek term Palaestina (Παλαιστίνη), appears to have been used as an Arabic adjectival noun in the region since as early as the 7th century CE.[7][8] The Ottomans divided Palestine into several Sanjaks with the Mutasarrifiyah ( special governate) of Jerusalem as directly linked to Constantinopole (Istanpole) untill 1918.[8]

During the British Mandate of Palestine, the term "Palestinian" was used to refer to all people residing there, regardless of religion or ethnicity, and those granted citizenship by the Mandatory authorities were granted "Palestinian citizenship".[9]

Following the 1948 establishment of the State of Israel as the national homeland of the Jewish people, the use and application of the terms "Palestine" and "Palestinian" by and to Palestinian Jews largely dropped from use. The English-language newspaper The Palestine Post for example — which, since 1932, primarily served the Jewish community in the British Mandate of Palestine — changed its name in 1950 to The Jerusalem Post. Jews in Israel and the West Bank today generally identify as Israelis. Arab citizens of Israel identify themselves as Israeli and/or Palestinian and/or Arab.[10]

The Palestinian National Charter, as amended by the PLO's Palestine National Council in July 1968, defined "Palestinians" as: "those Arab nationals who, until 1947, normally resided in Palestine regardless of whether they were evicted from it or stayed there. Anyone born, after that date, of a Palestinian father — whether in Palestine or outside it — is also a Palestinian."[11] This definition also extends to, "The Jews who had normally resided in Palestine until the beginning of the Zionist invasion." The Charter also states that "Palestine with the boundaries it had during the British Mandate, is an indivisible territorial unit."[12][11]

Palestinian perceptions of identity

In his 1997 book, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, historian Rashid Khalidi notes that the archaeological strata that denote the history of Palestine—encompassing the Biblical, Roman, Byzantine, Umayyad, Fatimid, Crusader, Ayyubid, Mamluk and Ottoman periods—form part of the identity of the modern-day Palestinian people, as they have come to understand it over the last century.[13] Khalidi stresses that Palestinian identity has never been an exclusive one, with "Arabism, religion, and local loyalties" continuing to play an important role.[14]

Echoing this view, Walid Khalidi writes that Palestinians in Ottoman times were "[a]cutely aware of the distinctiveness of Palestinian history ..." and that "[a]lthough proud of their Arab heritage and ancestry, the Palestinians considered themselves to be descended not only from Arab conquerors of the seventh century but also from indigenous peoples who had lived in the country since time immemorial, including the ancient Hebrews and the Canaanites before them."[15].

Ali Qleibo, a Palestinian anthropologist, explains how identity is "a discursive narrative that validates the present by selecting events, characters, and moments in time as formative beginnings."[16] Qleibo critiques Muslim historiography for assigning the beginning of Palestinian cultural identity to the advent of Islam in the seventh century.[16] In describing the effect of such a historiography, he writes: "Pagan origins are disavowed. As such the peoples that populated Palestine throughout history have discursively rescinded their own history and religion as they adopted the religion, language, and culture of Islam."[16]. That the peasant culture of the large fellahin class embodied strong elements of both pre-Arabic and pre-Israelitic traditions was a conclusion arrived at by the many Western scholars and explorers who mapped and surveyed Palestine in great detail throughout the latter half of the 19th century[17], and this assumption was to influence later debates on Palestinian identity by local ethnographers.

The contributions of the 'nativist' ethnographies produced by Tawfiq Canaan and other Palestinian writers and published in The Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society (1920-1948) indicate that the disavowal of pre-Islamic roots was not complete. Canaan and his colleagues were driven by the concern that the "native culture of Palestine", and in particular peasant society, was being undermined by the forces of modernity.[18] Salim Tamari writes that:

"Implicit in their scholarship (and made explicit by Canaan himself) was another theme, namely that the peasants of Palestine represent—through their folk norms ... the living heritage of all the accumulated ancient cultures that had appeared in Palestine (principally the Canaanite, Philistine, Hebraic, Nabatean, Syrio-Aramaic and Arab)."[18]

. Indeed, the folklorist revival among Palestinian intellectuals such as Nimr Sirhan, Musa Allush, Salim Mubayyid, and the Palestinian Folklore Society of the 1970s, emphasized pre-Islamic (and pre-Hebraic) cultural roots, re-constructing Palestinian identity with a focus on Canaanite and Jebusite cultures.[18] Such efforts seem to have borne fruit as evidenced in the organization of celebrations like the Qabatiya Canaanite festival and the annual Music Festival of Yabus by the Palestinian Ministry of Culture.[18] Nonetheless, some Palestinians, like Zakariyya Muhammad, have criticized "Canaanite ideology" as an "intellectual fad, divorced from the concerns of ordinary people."[18]

Emergent Palestinian nationalism

The timing and causes behind the emergence of a distinctively Palestinian national consciousness among the Arabs of Palestine are matters of scholarly disagreement. Rashid Khalidi argues that the modern national identity of Palestinians has its roots in nationalist discourses that emerged among the peoples of the Ottoman empire in the late 19th century, and which sharpened following the demarcation of modern nation-state boundaries in the Middle East after World War I.[14] Khalidi also states that although the challenge posed by Zionism played a role in shaping this identity, that "it is a serious mistake to suggest that Palestinian identity emerged mainly as a response to Zionism."[14]

In contrast, historian James L. Gelvin argues that Palestinian nationalism was a direct reaction to Zionism. In his book The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War he states that “Palestinian nationalism emerged during the interwar period in response to Zionist immigration and settlement.”[19] Gelvin argues that this fact does not make the Palestinian identity any less legitimate:

The fact that Palestinian nationalism developed later than Zionism and indeed in response to it does not in any way diminish the legitimacy of Palestinian nationalism or make it less valid than Zionism. All nationalisms arise in opposition to some "other." Why else would there be the need to specify who you are? And all nationalisms are defined by what they oppose.[19]

| Part of a series on |

| Palestinians |

|---|

|

| Demographics |

| Politics |

|

| Religion / religious sites |

| Culture |

| List of Palestinians |

Whatever the causal mechanism, by the early 20th century strong opposition to Zionism and evidence of a burgeoning nationalistic Palestinian identity is found in the content of Arabic-language newspapers in Palestine, such as Al-Karmil (est. 1908) and Filasteen (est. 1911).[20] Filasteen, published in Jaffa by Issa and Yusef al-Issa, addressed its readers as "Palestinians",[21] first focusing its critique of Zionism around the failure of the Ottoman administration to control Jewish immigration and the large influx of foreigners, later exploring the impact of Zionist land-purchases on Palestinian peasants ((Arabic: فلحين, fellahin), expressing growing concern over land dispossession and its implications for the society at large.[20]

The historical record also reveals an interplay between "Arab" and "Palestinian" identities and nationalisms. The idea of a unique Palestinian state separated out from its Arab neighbors was at first rejected by some Palestinian representatives. The First Congress of Muslim-Christian Associations (in Jerusalem, February 1919), which met for the purpose of selecting a Palestinian Arab representative for the Paris Peace Conference, adopted the following resolution: "We consider Palestine as part of Arab Syria, as it has never been separated from it at any time. We are connected with it by national, religious, linguistic, natural, economic and geographical bonds."[22] After the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the French conquest of Syria, however, the notion took on greater appeal.

Under the Ottomans, Palestine's Arab population mostly saw themselves as Ottoman subjects. Kimmerling and Migdal consider the revolt in 1834 of the Arabs in Palestine as the first formative event of the Palestinian people. In the 1830s Palestine was occupied by the Egyptian vassal of the Ottomans, Muhammad Ali and his son Ibrahim Pasha. The revolt was precipitated by popular resistance against heavy demands for conscripts. Peasants were well aware that conscription was little more than a death sentence. Starting in May 1834 the rebels took many cities, among which Jerusalem, Hebron and Nablus. In reaction Ibrahim Pasha send an army and finally defeated the last rebels on 4 August in Hebron.[23] Nevertheless, the Arabs in Palestine remained part of a Pan-Islamist or Pan-Arab national movement.[24]

At the beginning of the 20th century, a "local and specific Palestinian patriotism" emerged. The Palestinian identity grew progressively. In 1911, a newspaper named Filastin was published in Jaffa and the first Palestinian nationalist organisations appeared at the end of the World War I[25] Two political factions emerged. Al-Muntada al-Adabi, dominated by the Nashashibi family, militated for the promotion of the Arab language and culture, for the defense of Islamic values and for an independent Syria and Palestine. In Damascus, al-Nadi al-Arabi , dominated by the Husayni family, defended the same values.[26]

Palestinian Arab nationalism as a distinctive movement appeared between April and July 1920[27], after the Nebi Musa riots, the San Remo conference and the failure of Faisal to establish the Kingdom of Greater Syria.[28][29] At that time, the formerly pan-Syrianist mayor of Jerusalem, Musa Qasim Pasha al-Husayni, said "Now, after the recent events in Damascus, we have to effect a complete change in our plans here. Southern Syria no longer exists. We must defend Palestine".[citation needed]

In 1922, the British authorities over Mandate Palestine proposed a draft constitution which would have granted the Palestinian Arabs representation in a Legislative Council. The Palestine Arab delegation rejected the proposal as "wholly unsatisfactory," noting that "the People of Palestine" could not accept the inclusion of the Balfour Declaration in the constitution's preamble, as the basis for discussions, and further taking issue with the designation of Palestine as a British "colony of the lowest order."[30] The Arabs tried to get the British to offer an Arab legal establishment again roughly ten years later, but to no avail.[31]

Conflict between Palestinian nationalists and various types of pan-Arabists continued during the British Mandate, but the latter became increasingly marginalized. Two prominent leaders of the Palestinian nationalists were Mohammad Amin al-Husayni, Grand Mufti of Jerusalem,appointed by the British, and Izz ad-Din al-Qassam.[32] Followers of Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam, who was killed by the British in 1935, initiated the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine which began with a general strike and attacks on Jewish and British installations in Nablus.[32] The call for a general strike, non-payment of taxes, and the closure of municipal governments was met and by the end of 1936, the movement had become a national revolt, often credited as marking the birth of the "Arab Palestinian identity".[32]

Palestinians struggle against occupation

Against the British mandate 1917-1948

[9] 1920 Palestine riots 1936-1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

The "lost years" (1948 - 1967)

After the 1948 Arab-Israeli war and the accompanying Palestinian exodus[10], known to Palestinians as Al Nakba (the "catastrophe"), there was a hiatus in Palestinian political activity which Khalidi partially attributes to "the fact that Palestinian society had been devastated between November 1947 and mid-May 1948 as a result of a series of overwhelming military defeats of the disorganized Palestinians by the armed forces of the Zionist movement."[33] Those parts of British Mandate Palestine which did not become part of the newly declared Israeli state were occupied by Egypt and Jordan. During what Khalidi terms the "lost years" that followed, Palestinians lacked a center of gravity, divided as they were between these countries and others such as Syria, Lebanon, and elsewhere.[34]

In the 1950s, a new generation of Palestinian nationalist groups and movements began to organize clandestinely, stepping out onto the public stage in the 1960s.[35] The traditional Palestinian elite who had dominated negotiations with the British and the Zionists in the Mandate, and who were largely held responsible for the loss of Palestine, were replaced by these new movements whose recruits generally came from poor to middle class backgrounds and were often students or recent graduates of universities in Cairo, Beirut and Damascus.[35] The potency of the pan-Arabist ideology put forward by Gamel Abdel Nasser—popular among Palestinian for whom Arabism was already an important component of their identity[36]—tended to obscure the identities of the separate Arab nation-states it subsumed.[37]

Recent developments in Palestinian identity (1967 - present)

Since 1967, pan-Arabism has diminished as an aspect of Palestinian identity. The Israeli capture of the Gaza Strip and West Bank in the 1967 Six-Day War prompted fractured Palestinian political and militant groups to give up any remaining hope they had placed in pan-Arabism. Instead, they rallied around the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and its nationalistic orientation.[38] Mainstream secular Palestinian nationalism was grouped together under the umbrella of the PLO whose constituent organizations include Fateh and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, among others. [39] These groups have also given voice to a tradition that emerged in 1960s that argues Palestinian nationalism has deep historical roots, with extreme advocates reading a Palestinian nationalist consciousness and identity back into the history of Palestine over the past few centuries, and even millennia, when such a consciousness is in fact relatively modern.[40]

The Battle of Karameh and the events of Black September in Jordan contributed to growing Palestinian support for these groups. In 1974, the PLO was recognized as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people by the Arab states and was granted observer status as a national liberation movement by the United Nations that same year.[4][41] Israel rejected the resolution, calling it "shameful".[42] In a speech to the Knesset, Deputy Premier and Foreign Minister Yigal Allon outlined the government's view that: 'No one can expect us to recognize the terrorist organization called the PLO as representing the Palestinians—because it does not. No one can expect us to negotiate with the heads of terror-gangs, who through their ideology and actions, endeavour to liquidate the State of Israel.'[42]

The British historian Eric Hobsbawn allows that an element of justness can be discerned in skeptical outsider views that dismiss the propriety of using the term 'nation' to peoples like the Palestinians: such language arises often as the rhetoric of an evolved minority out of touch with the larger community that lacks this modern sense of national belonging. But at the same time, he argues, this outsider perspective has tended to "overlook the rise of mass national identification when it did occur, as Zionist and Israeli Jews notably did in the case of the Palestinian Arabs."[43]

From 1948 through until the 1980’s, according to Eli Podeh, professor at Hebrew University, the textbooks used in Israeli schools tried to disavow a unique Palestinian identity, referring to 'the Arabs of the land of Israel' instead of 'Palestinians.' Israeli textbooks now widely use the term 'Palestinians.' Podeh believes that Palestinian textbooks of today resemble those from the early years of the Israeli state.[44]

Various declarations, such as the PLO's 1988 proclamation of a State of Palestine, have further served to reinforce the Palestinian national identity.[citation needed] Today, most Palestinian organizations conceive of their struggle as either Palestinian-nationalist or Islamic in nature, and these themes predominate even more today. Within Israel itself, there are political movements, such as Abnaa el-Balad that assert their Palestinian identity, to the exclusion of their Israeli one.

Palestinian ethnic identity today is based primarily on two elements: the village of origin and family networks. The village of origin holds a privileged place in Palestinian memory because of its historically important role as a center for religious and political power throughout Palestine's administration by various empires. The village of origin also represents "the very expression of their Arabic Palestinian culture and identity," and is a site central to kinship and familial ties. The progressive deterritorialization experienced by Palestinians has rendered the village of origin a symbol of lost territory, and it forms a central part of a diasporic consciousness among Palestinians.[45]

Intifada

First Intifada (War of the Stones) 1978-1993. Second Intifada (Al-Aqsa Intifada) 2000- Present.[11][12]

Demographics

In the absence of a comprehensive census including all Palestinian diaspora populations, and those that have remained within what was British Mandate Palestine, exact population figures are difficult to determine.

| Country or region | Population |

|---|---|

| West Bank and Gaza Strip | 3,760,000[46] |

| Jordan | 3,000,000[47] |

| Israel | 1,318,000[48] |

| Syria | 434,896[49] |

| Lebanon | 405,425[49] |

| Chile | 300,000[50] |

| Saudi Arabia | 327,000[48] |

| The Americas | 225,000[51] |

| Egypt | 44,200[51] |

| Kuwait | (approx) 40,000[48] |

| Other Gulf states | 159,000[48] |

| Other Arab states | 153,000[48] |

| Other countries | 308,000[48] |

| TOTAL | 10,574,521 |

The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) announced on October 20, 2004 that the number of Palestinians worldwide at the end of 2003 was 9.6 million, an increase of 800,000 since 2001.[52]

In 2005, a critical review of the PCBS figures and methodology was conducted by the American-Israel Demographic Research Group.[53] In their report,[54] they claimed that several errors in the PCBS methodology and assumptions artificially inflated the numbers by a total of 1.3 million. The PCBS numbers were cross-checked against a variety of other sources (e.g., asserted birth rates based on fertility rate assumptions for a given year were checked against Palestinian Ministry of Health figures as well as Ministry of Education school enrollment figures six years later; immigration numbers were checked against numbers collected at border crossings, etc.). The errors claimed in their analysis included: birth rate errors (308,000), immigration & emigration errors (310,000), failure to account for migration to Israel (105,000), double-counting Jerusalem Arabs (210,000), counting former residents now living abroad (325,000) and other discrepancies (82,000). The results of their research was also presented before the United States House of Representatives on March 8, 2006. [55]

The study was criticised by Sergio DellaPergola, a demographer at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.[56] DellaPergola accused the authors of misunderstanding basic principles of demography on account of their lack of expertise in the subject. He also accused them of selective use of data and multiple systematic errors in their analysis. For example, DellaPergola claimed that the authors assumed the Palestinian Electoral registry to be complete even though registration is voluntary and good evidence exists of incomplete registration, and similarly that they used an unrealistically low Total Fertility Ratio (a statistical abstraction of births per woman) incorrectly derived from data and then used to reanalyse that data in a "typical circular mistake".

DellaPergola himself estimated the Palestinian population of the West Bank and Gaza at the end of 2005 as 3.33 million, or 3.57 million if East Jerusalem is included. These figures are only slightly lower than the official Palestinian figures.[56]

In Jordan today, there is no official census data that outlines how many of the inhabitants of Jordan are Palestinians, but estimates by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics cite a population range of 50% to 55%. [57][58]

Many Arab Palestinians have settled in the United States, particularly in the Chicago area.[59][60]

In total, an estimated 600,000 Palestinians are thought to reside in the Americas. Arab Palestinian emigration to South America began for economic reasons that pre-dated the Arab-Israeli conflict, but continued to grow thereafter.[61] Many emigrants were from the Bethlehem area. Those emigrating to Latin America were mainly Christian. Half of those of Palestinian origin in Latin America live in Chile. El Salvador[62] and Honduras[63] also have substantial Arab Palestinian populations. These two countries have had presidents of Palestinian ancestry (in El Salvador Antonio Saca, currently serving; in Honduras Carlos Roberto Flores Facusse). Belize, which has a smaller Palestinian population, has a Palestinian minister — Said Musa.[64] Schafik Jorge Handal, Salvadoran politician and former guerrilla leader, was the son of Palestinian immigrants.[13]

Refugees

There are 4,255,120 Palestinians registered as refugees with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). This number includes the descendants of refugees from the 1948 war, but excludes those who have emigrated to areas outside of UNRWA's remit.[49] Based on these figures, almost half of all Palestinians are registered refugees. The 993,818 Palestinian refugees in the Gaza Strip and 705,207 Palestinian refugees in the West Bank who hail from towns and villages that now located in Israel are included in these UNRWA figures.[65] UNRWA figures do not include some 274,000 people, or 1 in 4 of all Arab citizens of Israel, who are internally displaced Palestinian refugees.[66][67]

Virtually every Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and the West Bank is organized according to a refugee family's village or place of origin. Among the first things that children born in the camps learn is the name of their village of origin. David McDowall writes that, "[...] a yearning for Palestine permeates the whole refugee community and is most ardently espoused by the younger refugees, for whom home exists only in the imagination."[68]

Religion

Background

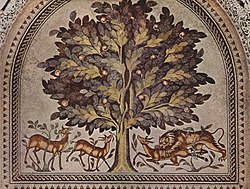

Until the end of the nineteenth century, most villages in the countryside did not have local mosques. Cross-cultural syncretism between Biblical and Islamic symbols and figures in religious practice was common.[16] For example, Jonah is worshipped in Halhul as both a Biblical and Islamic prophet and St. George, known to Muslims as el Khader, is another shared symbol. Villagers would pay tribute to local patron saints at a maqam — a domed single room often placed in the shadow of an ancient carob or oak tree.[16] Saints, taboo by the standards of orthodox Islam, mediated between man and Allah, and shrines to saints and holy men dotted the Palestinian landscape.[16] Ali Qleibo, a Palestinian anthropologist, states that this built evidence constitutes "an architectural testimony to Christian/Moslem Palestinian religious sensibility and its roots in ancient Semitic religions."[16]

Religion as constitutive of individual identity was accorded a minor role within Palestinian tribal social structure until the latter half of the 19th century.[16] Jean Moretain, a priest writing in 1848, wrote that a Christian in Palestine was "distinguished only by the fact that he belonged to a particular clan. If a certain tribe was Christian, then an individual would be Christian, but without knowledge of what distinguished his faith from that of a Muslim."[16]

The concessions granted to France and other Western powers by the Ottoman Sultanate in the aftermath of the Crimean War had a significant impact on contemporary Palestinian religious cultural identity.[16] Religion was transformed into an element "constituting the individual/collective identity in conformity with orthodox precepts", and formed a major building block in the political development of Palestinian nationalism.[16]

The British census of 1922 registered 752,048 inhabitants in Palestine, consisting of 589,177 Palestinian Muslims, 83,790 Palestinian Jews, 71,464 Palestinian Christians (including Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and others) and 7,617 persons belonging to other groups. The corresponding percentage breakdown is 78% Muslim, 11% Jewish, and 9% Christian. Palestinian Bedouin were not counted in the census, but a 1930 British study estimated their number at 70,860.[69]

Today

Currently, no comprehensive data on religious affiliation among the worldwide Palestinian population is available. Bernard Sabella of Bethlehem University estimates that 6% of the Palestinian population is Christian.[70] According to the Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs, the Palestinian population of the West Bank and Gaza Strip is 97% Muslim and 3% Christian. [71]

All of the Druze living in what was then British Mandate Palestine became Israeli citizens, though some individuals self-identify "Palestinian Druze".[72] According to Salih al-Shaykh, most Druze do not consider themselves to be Palestinian: "their Arab identity emanates in the main from the common language and their socio-cultural background, but is detached from any national political conception. It is not directed at Arab countries or Arab nationality or the Palestinian people, and does not express sharing any fate with them. From this point of view, their identity is Israel, and this identity is stronger than their Arab identity".[73]

There are also about 350 Samaritans who carry Palestinian identity cards and live in the West Bank while a roughly equal number live in Holon and carry Israeli citizenship.[74] Those who live in the West Bank also are represented in the legislature for the Palestinian National Authority.[74] They are commonly referred to among Palestinians as the "Jews of Palestine."[74]

Jews who identify as Palestinian Jews are few, but include Israeli Jews who are part of the Neturei Karta group,[75] and Uri Davis, an Israeli citizen and self-described Palestinian Jew who serves as an observer member in the Palestine National Council.[76]

Culture

Palestinian culture is most closely related to the cultures of the nearby Levantine countries such as Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan and of the Arab World. It includes unique art, literature, music, costume and cuisine. Though separated geographically, Palestinian culture continues to survive and flourish in the Palestinian territories, Israel and the Diaspora.

Poetry

Poetry, using classical pre-Islamic forms, remains an extremely popular art form, often attracting Palestinian audiences in the thousands. Until 20 years ago, local folk bards reciting traditional verses were a feature of every Palestinian town.[77]

After the 1948 Palestinian exodus, poetry was transformed into a vehicle for political activism. From among those Palestinians who became Arab citizens of Israel after the passage of the Citizenship Law in 1952, a school of resistance poetry was born that included poets like Mahmoud Darwish, Samih al-Qasim, and Tawfiq Zayyad.[77]

The work of these poets was largely unknown to the wider Arab world for years because of the lack of diplomatic relations between Israel and Arab governments. The situation changed after Ghassan Kanafani, another Palestinian writer in exile in Lebanon published an anthology of their work in 1966.[77]

Palestinian poets often write about the common theme of a strong affection and sense of loss and longing for a lost homeland.[77]

Art

Similar to the structure of Palestinian society, the Palestinian art field extends over four main geographic centers: 1) the West Bank and Gaza Strip 2) Israel 3) the Palestinian diaspora in the Arab world, and 4) the Palestinian diaspora in Europe and the United States.[78]

Contemporary Palestinian art finds its roots in folk art and traditional Christian and Islamic painting popular in Palestine over the ages. After the 1948 Palestinian exodus, nationalistic themes have predominated as Palestinian artists use diverse media to express and explore their connection to identity and land.[79]

Literature

The long history of the Arabic language and its rich written and oral tradition form part of the Palestinian literary tradition as it has developed over the course of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Intellectuals

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, Palestinian intellectuals were integral parts of wider Arab intellectual circles, as represented by individuals such as May Ziade and Khalil Beidas.

Diaspora figures like Edward Said and Ghada Karmi, Arab citizens of Israel like Emile Habibi, refugee camp residents like Ibrahim Nasrallah have made contributions to a number of fields, exemplifying the diversity of experience and thought among Palestinians.

Film

Palestinian cinema is relatively young compared to Arab cinema overall and many Palestinian movies are made with European and Israeli support.[16] Palestinian films are not exclusively produced in Arabic; some are made in English, French or Hebrew.[17] More than 800 films have been produced about Palestinians, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and other related topics.

Folklore

Palestinian Folklore is the body of expressive culture, including tales, music, dance, legends, oral history, proverbs, jokes, popular beliefs, customs, and comprising the traditions (including oral traditions) of Palestinian culture

Dance

Villageres have danced the Dabke since ancient phoenician times celebrating days of feast.[citation needed]

Folk tales

Traditional storytelling among Palestinians is prefaced with an invitation to the listeners to give blessings to God and the Prophet Mohammed or the Virgin Mary as the case may be, and includes the traditional opening: "There was, or there was not, in the oldness of time ..."[77]

Formulaic elements of the stories share much in common with the wider Arab world, though the rhyming scheme is distinct. There are a cast of supernatural characters: djinns who can cross the Seven Seas in an instant, giants, and ghouls with eyes of ember and teeth of brass. Stories invariably have a happy ending, and the storyteller will usually finish off with a rhyme like: "The bird has taken flight, God bless you tonight," or "Tutu, tutu, finished is my haduttu (story)."[77]

Costumes

Foreign travelers to Palestine in late 19th and early 20th centuries often commented on the rich variety of costumes among the Palestinian people, and particularly among the fellaheen or village women.

Until the 1940s, a woman's economic status, whether married or single, and the town or area they were from could be deciphered by most Palestinian women by the type of cloth, colors, cut, and embroidery motifs, or lack thereof, used for the dress.[80]

Though such local and regional variations largely disappeared after the 1948 Palestinian exodus, Palestinian embroidery and costume continue to be produced in new forms and worn alongside Islamic and Western fashions.

Music

Palestinian music is well-known and respected throughout the Arab world. A new wave of performers emerged with distinctively Palestinian themes following the 1948 Palestinian exodus, relating to the dreams of statehood and the burgeoning nationalist sentiments.

Cuisine

Palestinian cuisine is divided into two groups: In the Galilee and northern West Bank the cuisine is similar to that of Lebanon and Syria while other parts of the West Bank, such as the Jerusalem, and the Hebron region, locals have a heavy cooking style of their own. Gaza is more likely to be piquant, incorporating fresh green or dried red hot peppers, reflecting the culinary influences of Egypt. Some of the Palestinian cuisine now famous in the Arab world and around the world are: Kinafe Nabulsi ( from Nablus), Nabulsi Cheese, Nabulsi Halva, Akka Cheese (Cheese of Acre), the Baklava that became famous during the Ottoman empire by promotion from the Sultan Sulaiman the Magnificient after finishing Jerusalem wall project is of Palestinian origins and became a Sultan gift to the Public upon victories of the Empire.[citation needed] Finally Falafel and Hummus are a Palestinian patent created in the Middle ages after Indian pepper imports became available in the Middle East after the Mongol trade road, that spread all over Syria, Lebanon and Palestine.[citation needed]

Mezze describes an assortment of dishes laid out on the table for a meal that takes place over several hours, a characteristic common to Mediterranean cultures. Some common mezze dishes are hummus, tabouleh, baba ghanoush (fried eggplant), labaneh, and zate 'u zaatar which is the pita bread dipping of olive oil and ground thyme and sesame seeds. Kebbiyeh or kubbeh is another popular dish made of minced meat enclosed in a case of burghul (cracked wheat) and deep fried. A Hebron dish is called Qidrah

Famous entrées in Palestine are waraq al-'inib—boiled grape leaves wrapped around cooked rice and ground lamb. One of the most distinctive Palestinian dishes, said to originate in the Northern West Bank, near Jenin and Tulkarem, is musakhan—roasted chicken smothered in fried onions, pine nuts, and sumac (a dark red, lemony flavored spice), and laid over taboon.

Pottery

Palestinian pottery shows a remarkable continuity throughout the ages. Modern Palestinian pots, bowls, jugs and cups, particularly those produced prior to the establishment of Israel in 1948, are similar in shape, fabric and decoration to their ancient equivalents.[81] Cooking pots, jugs, mugs and plates that are still hand-made and fired in open, charcoal-fuelled kilns as in ancient times in historic villages like al-Jib (Gibeon), Beitin (Bethel) and Senjel.[82]

Language

Palestinian Arabic is a subgroup of the broader Levantine Arabic dialect spoken by Palestinians. It has three primary sub-variations with the pronunciation of the qāf serving as a shibboleth to distinguish between the three main Palestinian dialects: In most cities, it is a glottal stop; in smaller villages and the countryside, it is a pharyngealized k; and in the far south, it is a g, as among Bedouin speakers. In a number of villages in the Galilee (e.g. Maghār), and particularly, though not exclusively among the Druze, the qāf is actually pronounced qāf as in Classical Arabic.

Barbara McKean Parmenter has noted that the Arabs of Palestine have been credited with the preservation of the indigenous Semitic place names for many sites mentioned in the Bible which were documented by the American archaeologist Edward Robinson in the early 20th century.[83]

Ancestry of the Palestinians

Palestinians, like most other Arabic-speakers, combine ancestries from those who have come to settle the region throughout history, a matter on which genetic evidence (see below) has begun to shed some light.[84] Ali Qleibo, a Palestinian anthropologist writes:

"Throughout history a great diversity of peoples has moved into Palestine as their homeland: Jebusites, Canaanites, Philistines from Crete, Anatolian and Lydian Greeks, Hebrews, Amorites, Edomites, Nabateans, Arameans, Romans, Arabs, and European crusaders, to name a few. Each of them appropriated different regions that overlapped in time and competed for sovereignty and land. Others, such as Ancient Egyptians, Hittites, Persians, Babylonians, and Mongols, were historical 'events' whose successive occupations were as ravaging as the effects of major earthquakes ... Like shooting stars, the various cultures shine for a brief moment before they fade out of official historical and cultural records of Palestine. The people, however, survive. In their customs and manners, fossils of these ancient civilizations survived until modernity—albeit modernity camouflaged under the veneer of Islam and Arabic culture."

[16] Bernard Lewis, an American historian writes:

"Clearly, in Palestine as elsewhere in the Middle East, the modern inhabitants include among their ancestors those who lived in the country in antiquity. Equally obviously, the demographic mix was greatly modified over the centuries by migration, deportation, immigration, and settlement. This was particularly true in Palestine..."[85]

For example, much of the local Palestinian population in Nablus is believed to be descended from Samaritans who converted to Islam.[86] Even today, certain Nabulsi family names including Muslimani, Yaish, and Shakshir among others, are associated with Samaritan ancestry.[86]

Semitic tribes from the Arabian peninsula began migrating into Palestine as early as the 3rd millennium BCE,[87][88] and among these migrants were the Arabs, such that the region was Arabized centuries before the Islamic era began.[89][90] Aramaic and Greek were replaced by Arabic as the area's dominant language.[91] Among the cultural survivals from pre-Islamic times are the significant Palestinian Christian community, and smaller Jewish and Samaritan ones, as well as an Aramaic and possibly Hebrew sub-stratum in the local Palestinian Arabic dialect.[92]

The Bedouins of Palestine are said to be more securely known to be Arab ancestrally as well as by culture; their distinctively conservative dialects and pronunciation of qaaf as gaaf group them with other Bedouin across the Arab world and confirm their separate history.[citation needed] Arabic onomastic elements began to appear in Edomite inscriptions starting in the 6th century BC, and are nearly universal in the inscriptions of the Nabataeans, who arrived in today’s Jordan in the 4th-3rd centuries BC.[93] It has thus been suggested that the present day Bedouins of the region may have their origins as early as this period. A few Bedouin are found as far north as Galilee; however, these seem to be much later arrivals, rather than descendants of the Arabs that Sargon II settled in Samaria in 720 BC. The term “Arab,” as well as the presence of Arabs in the Syrian desert and the Fertile Crescent, is first seen in the Assyrian sources from the 9th century bce (Eph'al 1984).[94]

Canaanite claims

| History of the Levant |

|---|

| Prehistory |

| Ancient history |

| Classical antiquity |

| Middle Ages |

| Modern history |

The claim that Palestinians are direct descendants of the region's earliest inhabitants, the Canaanites, has been put forward by some authors. Marcia Kunstel and Joseph Albright, author-journalists, for example put forward this claim in their 1990 book Their Promised Land: Arab and Jew in History's Cauldron-One Valley in the Jerusalem Hills.[95] Kathleen Christison notes in her review of the work that Kunstel and Albright are "those rare historians who give credence to the Palestinians' claim that their 'origins and early attachment to the land' derive from the Canaanites five millennia ago, and that they are an amalgamation of every people who has ever lived in Palestine."[96]

Adel Yahya, a Palestinian archaeologist, also claims that modern-day Palestinians are the direct descendants of the Philistines and that they might be descendants of the ancient Canaanites.[97] Sandra Scham, an American archaeologist at the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Jerusalem and author of Archaeology of the Disenfranchised dismissed such conclusions as falling into the realm of 'popular imagination and folklore.'[97]

In an article in the journal Science, it was reported that "most Palestinian archaeologists were quick to distance themselves from these ideas," with the reasons cited by those interviewed centering around the view that the issue of who was in Palestine first constitutes an ideological issue that lies outside of the realm of archaeological study.[98] Bernard Lewis writes that, "The rewriting of the past is usually undertaken to achieve specific political aims... in bypassing the biblical Israelites and claiming kinship with the Canaanites, the pre-Israelite inhabitants of Palestine, it is possible to assert a historical claim antedating the biblical promise and possession put forward by the Jews."[99]

Zakariyya Mohammed also assigns the search for Canaanite roots to a desire to predate Jewish national claims. Describing "Canaanism" as a "losing ideology when used to manage our conflict with the Zionist movement," he writes that, "'Canaanism' concedes a priori the central thesis of Zionism. Namely that we have been engaged in a perennial conflict with Zionism—and hence with the Jewish presence in Palestine—since the Kingdom of Solomon and before ... thus in one stroke Canaanism cancels the assumption that Zionism is a European movement, propelled by modern European contingencies..."[18]

Salim Tamari posits that the Canaanite revivalist writings following the war of 1948 were a reaction to Zionist attempts at establishing their own claims to Israelite and biblical motifs.[18] Like Mohammed, Tamari also criticized this tendency for giving up "any attempt to relocate (or even relate) modern Palestinian cultural affinities to biblical roots. They seem to have abandoned this patrimony of biblical representation to Jewish nationalist discourse, in a paradoxical manner, reinforcing the claims of their protagonists. [Tawfiq] Canaan and his group, by contrast, were not Canaanites. They contested Zionist claims to biblical patrimonies by stressing present day continuities between the biblical heritage (and occasionally pre-biblical roots) and Palestinian popular beliefs and practices."[18]

Tamari further notes the paradoxes that emerged in a parallel search for 'nativist' roots among Zionists and the so-called Canaanite (anti-Zionist) followers of Yonatan Ratosh.[18] He cites the example of Ber Borochov who claimed that the lack of a crystallized national consciousness among Palestinian Arabs would result in their likely assimilation into the new Hebrew nationalism, basing this on the belief that: "the fellahin are considered in this context as the descendants of the ancient Hebrew and Canaanite residents 'together with a small admixture of Arab blood'".[18] Ahad Ha'am also shared the belief that: "the Moslems [of Palestine] are the ancient residents of the land ... who became Christians on the rise of Christianity and became Moslems on the arrival of Islam."[18] Even David Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Ben Zvi tried to establish in a 1918 paper written in Yiddish that Palestinian peasants and their mode of life were living historical testimonies to Israelite practices in the biblical period.[18] Tamari notes that "the ideological implications of this claim became very problematic and were soon withdrawn from circulation."[18]

DNA clues

Results of a DNA study by geneticist Ariella Oppenheim matched historical accounts that "some Muslim Arabs are descended from Christians and Jews who lived in the southern Levant, a region that includes Israel and the Sinai. They were descendants of a core population that lived in the area since prehistoric times."[100].

In genetic genealogy studies, Palestinians and Negev Bedouins have the highest rates of Haplogroup J1 (Y-DNA) among all populations tested (62.5%).[101]Arab and other Semitic populations usually possess an excess of J1 Y chromosomes compared to other populations harboring Y-haplogroup J[102][103][104][105][106][107] The haplogroup J1, associated with marker M267, originates south of the Levant and was first disseminated from there into Ethiopia and Europe in Neolithic times; a second diffusion of the marker took place in the seventh century CE when Arabs brought it from the Arabia to North Africa.[103] J1 is most common in the southern Levant, as well as Syria, Iraq, Algeria, and Arabia, and drops sharply at the border of non-Arab areas like Turkey and Iran. While it is also found in Jewish populations (<15%), haplogroup J2 (M172)( of eight sub-Haplogroups), is almost twice as common as J1 among Jews (<29%)

Haplogroup J1 (Y-DNA) includes the modal haplotype of the Galilee Arabs (Nebel et al. 2000) and of Moroccan Arabs (Bosch et al. 2001) and the sister Modal Haplotype of the Cohanim, the "Cohan Modale Haplotype", representing the descendents of the priestly caste Aaron. J2 is known to be related to the ancient Greek movements and is found mainly in Europe and the central Mediterranean ( Italy, the Balkans, Greece). According to a 2002 study by Nebel et al., on Genetic evidence for the expansion of Arabian tribes, the highest frequency of Eu10 (i.e. J1) (30%–62.5%) has been observed so far in various Muslim Arab populations in the Middle East. (Semino et al. 2000; Nebel et al. 2001).[108] The most frequent Eu10 microsatellite haplotype in Northwest Africans is identical to a modal haplotype of Muslim Arabs who live in a small area in the north of Israel, the Galilee. (Nebel et al. 2000) termed the modal haplotype of the Galilee (MH Galilee). The term “Arab,” as well as the presence of Arabs in the Syrian desert and the Fertile Crescent, is first seen in the Assyrian sources from the 9th century B.C.E. (Eph'al 1984).[109]

In recent years, many genetic surveys have suggested that, at least paternally, most of the various Jewish ethnic divisions and the Palestinians — and in some cases other Levantines — are genetically closer to each other than the Palestinians or European Jews to non-Jewish Europeans (a Europpean sample from the Welsh.[110] [111]. However, Nebel et al. (2001) report that Jews were found to be more closely related to groups in the north of the Fertile Crescent (Kurds, Turks, and Armenians) than to their Arab neighbors.[112]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ [i]Some three million Palestinians also live in modern day Jordan. From 1918-22 this region was part of the British Mandate of Palestine, before being separated to form Transjordan. Unless otherwise specified this article uses "British Mandate" and related terms to refer to the post-1922 mandate, west of the Jordan river.

- ^ a b Palestine. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 29, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Cite error: The named reference "palestineeb" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Porath, 1974, p. 117.

- ^ Abbas Shiblak (2005). "Reflections on the Palestinian Diaspora in Europe" (PDF). The Palestinian Diaspora in Europe: Challenges of Dual Identity and Adaptation. Institute of Jerusalem Studies. ISBN 9950315042.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Who Represents the Palestinians Officially Before the World Community?". Institute for Middle East Understanding. 2006–2007. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- ^ With the exception of Bks.1,105; 3.91.1, and 4.39,2

- ^ Herodotus, The HistoriesBks.2,104: 3.5

- ^ W.W.How, J.Wells, A Commentary on Herodotus, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1912) 1979 vol.1 pp.256-257

- ^ Michael Lecker. "On the burial of martyrs". Tokyo University.:"For example, 'Abdallah b. Muhayriz al-Jumahi al-Filastini was the name of an ascetic who lived in Jerusalem and died in the early 700s"

- ^ Government of the United Kingdom (December 31, 1930). "REPORT by His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to the Council of the League of Nations on the Administration of PALESTINE AND TRANS-JORDAN FOR THE YEAR 1930". League of Nations. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Kershner, Isabel. "Noted Arab citizens call on Israel to shed Jewish identity" International Herald Tribune. 8 February 2007. 1 August 2007.

- ^ a b "The Palestinian National Charter". Permanent Observer Mission of Palestine to the United Nations.

- ^ Constitution Committee of the Palestine National Council (Third Draft, 7 March 2003, revised in March 25, 2003). "Constitution of the State of Palestine" (PDF). Jerusalem Media and Communication Center. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) The most recent draft of the Palestinian constitution would amend that definition such that, "Palestinian nationality shall be regulated by law, without prejudice to the rights of those who legally acquired it prior to May 10, 1948 or the rights of the Palestinians residing in Palestine prior to this date, and who were forced into exile or departed there from and denied return thereto. This right passes on from fathers or mothers to their progenitor. It neither disappears nor elapses unless voluntarily relinquished." - ^ Palestinian Identity:The Construction of Modern National Consciousness. Columbia University Press. 1997. p. 18. ISBN 0231105142.

- ^ a b c Khalidi 1997:19–21

- ^ Walid Khalidi (1984). Before Their Diaspora. Institute for Palestine Studies, Washington D.C. p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Dr. Ali Qleibo (28 July 2007). "Palestinian Cave Dwellers and Holy Shrines: The Passing of Traditional Society". This Week in Palestine. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ^ James Parkes, Whose Land? A History of the Peoples of Palestine(1949) Penguin 1970 pp.209-210

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Salim Tamari (Winter 2004). "Lepers, Lunatics and Saints: The Nativist Ethnography of Tawfiq Canaan and his Jerusalem Circle". Issue 20. Jerusalem Quarterly. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Gelvin, James L. (2005). "From Nationalism in Palestine to Palestinan Nationalism". The Israel-Palestine conflict: one hundred years of war (GoogleBooks). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp. p. 92–93. ISBN 0521852897. OCLC 59879560. LCCN 20-5 – 0. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Khalidi 1997:124–127

- ^ "Palestine Facts". PASSIA: Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs.

- ^ Yehoshua Porath (1977). Palestinian Arab National Movement: From Riots to Rebellion: 1929-1939, vol. 2. Frank Cass and Co., Ltd. p. 81-82.

- ^ Kimmerling & Migdal, 2003, 'The Palestinian people', p. 6-11

- ^ Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, pp.40-42 in the French edition.

- ^ Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, p.48 in the French edition.

- ^ Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, p.49 in the French edition.

- ^ Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, p.49 in the French edition.

- ^ Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, pp.49-50 in the French edition.

- ^ Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete, p.139n.

- ^ "Correspondence with the Palestine Arab Delegation and the Zionist Organization". United Nations (original from His Majesty's Stationery Office). 21 February 1922. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Palestine Arabs." The Continuum Political Encyclopedia of the Middle East. Ed. Avraham Sela. New York: Continuum, 2002.

- ^ a b c "The History of Palestinian Revolts". Al Jazeera. 9 December 2003. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ^ Khalidi 1997:178

- ^ Khalidi 1997:179

- ^ a b Khalidi 1997:180

- ^ Khalidi 1997:182

- ^ Khalidi 1997:181

- ^ "The PNC program of 1974". Mideastweb.org. 8 June 1974. Retrieved 2007-08-17.The PNC adopted the goal of establishing a national state in 1974.

- ^ Khalidi 1997: 149

- ^ Palestinian Identity:The Construction of Modern National Consciousness. Columbia University Press. 1997. p. 149. ISBN 0231105142.Khalidi writes : 'As with other national movements, extreme advocates of this view go further than this, and anachronistically read back into the history of Palestine over the past few centuries, and even millennia, a nationalist consciousness and identity that are in fact relatively modern.'

- ^ "Security Council" (PDF). WorldMUN2007 - United Nations Security Council. 26 March–30 March 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "48 Statement in the Knesset by Deputy Premier and Foreign Minister Allon- 26 November 1974". Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 26 November 1974. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ Eric Hobsbawm,Nations and Nationalism since 1780:Programme, myth, reality,, Cambridge University Press, 1990 p.152

- ^ Jennifer Miller. "Author Q & A". Random House: Academic Resources. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- ^ Nadje Sadig Al-Ali and Khalid Koser (2002). New Approaches to Migration?: Transnational Communities and the Transformation of Home. Routledge. p. 92. ISBN 0415254124.

- ^ [1] 2008 Census done by the Palestinian Authority. Includes Gaza, West Bank and East Jerusalem.

- ^ Palestinians in Diaspora, 1 January 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f Drummond, Dorothy Weitz (2004). Holy Land, Whose Land?: Modern Dilemma, Ancient Roots. Fairhurst Press. ISBN 0974823325 Cite error: The named reference "drummond" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c "Table 1.0: Total Registered Refugees per Country per Area" (PDF). UNRWA.

- ^ Boyle & Sheen, 1997, p. 111.

- ^ a b Cohen, Robin (1995). The Cambridge Survey of World Migration. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521444055 p. 415.

- ^ Statistical Abstract of Palestine No. 5.

- ^ [http://www.pademographics.com/ American-Israel Demographic Research Group (AIDRG)], is led by Bennett Zimmerman, Yoram Ettinger, Roberta Seid, and Michael L. Wise

- ^ Bennett Zimmerman, Roberta Seid & Michael L. Wise. "The Million Person Gap: The Arab Population in the West Bank and Gaza" (PDF). Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies.

- ^ Bennett Zimmerman, Roberta Seid, and Michael L. Wise, Voodoo Demographics, Azure, Summer 5766/2006, No. 25

- ^ a b Sergio DellaPergola, Letter to the editor, Azure, 2007, No. 27, [2]

- ^ Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (January 1, 2006). "Palestinians in Diaspora and in Historic Palestine End Year 2005". The Palestinian Nongovernmental Organization Network (PNGO).

- ^ Latimer Clarke Corporation Pty Ltd. "Jordan - Atlapedia Online:". Latimer Clarke Corporation Pty Ltd.

- ^ Ray Hanania. "Chicago's Arab American Community: An Introduction".

- ^ "Palestinians". Encyclopedia of Chicago.

- ^ Farsoun, 2004, p. 84.

- ^ Matthew Ziegler. "El Salvador: Central American Palestine of the West?". The Daily Star.

- ^ Larry Lexner. "Honduras: Palestinian Success Story". Lexner News Inc.

- ^ Guzmán, 2000, p. 85.

- ^ "Publications and Statistics". UNRWA. 31 March 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

- ^ Badil Resource Centre for Palestinian Refugee and Residency Rights

- ^ Internal Displacement Monitoring Center

- ^ David McDowall (1989). Palestine and Israel: The Uprising and Beyond. I.B.Tauris. p. 90. ISBN 1850432899.

- ^ Janet Abu-Lughod. "The Demographic War for Palestine". Americans for Middle East Understanding.

- ^ Bernard Sabella. "Palestinian Christians: Challenges and Hopes". Bethlehem University.

- ^ Dana Rosenblatt (October 14, 2002). "Amid conflict, Samaritans keep unique identity". CNN.

- ^ Yoav Stern & Jack Khoury (2 May 2007). "Balad's MK-to-be: 'Anti-Israelization' Conscientious Objector". Haaretz. Retrieved 2007-07-29.For example, Said Nafa, a self-identified "Palestinian Druze" serves as the head of the Balad party's national council and founded the "Pact of Free Druze" in 2001, an organization that aims "to stop the conscription of the Druze and claims the community is an inalienable part of the Arabs in Israel and the Palestinian nation at large."

- ^ Nissim Dana, The Druze in the Middle East: Their Faith, Leadership, Identity and Status, Sussex Academic Press, 2003, p. 201.

- ^ a b c Dana Rosenblatt (October 14, 2002). "Amid conflict, Samaritans keep unique identity". CNN.

- ^ Charles Glass (Autumn 1975–Winter 1976). "Jews against Zion: Israeli Jewish Anti-Zionism". 5 No. 1/2. Journal of Palestine Studies: 56–81.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Uri Davis (December 2003). "APARTHEID ISRAEL: A Critical Reading of the Draft Permanent Agreement, known as the "Geneva Accords"". The Association for One Democratic State in Palestine-Israel. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ a b c d e f Mariam Shahin (2005). Palestine: A Guide. Interlink Books. p. 41- 55.

- ^ Tal Ben Zvi (2006). "Hagar: Contemporary Palestinian Art" (PDF). Hagar Association. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ Gannit Ankori (1996). Palestinian Art. Reaktion Books. ISBN 1861892594.

- ^ Jane Waldron Grutz (January–February 1991). "Woven Legacy, Woven Language". Saudi Aramco World. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Winifred Needler (1949). Palestine: Ancient and Modern. Royal Ontario Museum of Archaeology. p. 75–76.

- ^ "PACE's Exhibit of Traditional Palestinian Handicrafts". PACE. Retrieved 2007-13-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Barbara McKean Parmenter (1994). "Giving Voice to Stones Place and Identity in Palestinian Literature". University of Texas Press. p. 11.

- ^ Nebel; et al. (2000). "High-resolution Y chromosome haplotypes of Israeli and Palestinian Arabs reveal geographic substructure and substantial overlap with haplotypes of Jews". 107. Human Genetics: 630–641.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)"According to historical records part, or perhaps the majority, of the Moslem Arabs in this country descended from local inhabitants, mainly Christians and Jews, who had converted after the Islamic conquest in the seventh century AD (Shaban 1971; Mc Graw Donner 1981). These local inhabitants, in turn, were descendants of the core population that had lived in the area for several centuries, some even since prehistorical times (Gil 1992)... Thus, our findings are in good agreement with the historical record..." - ^ Bernard Lewis, Semites and Anti-Semites: An Inquiry Into Conflict and Prejudice, W. W. Norton & Company, 1999, ISBN 0393318397, p. 49/

- ^ a b Sean Ireton (2003). "The Samaritans - A Jewish Sect in Israel: Strategies for Survival of an Ethno-religious Minority in the Twenty First Century". Anthrobase. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

- ^ Bernard Lewis (2002). The Arabs in History. Oxford University Press, USA, 6th ed. p. 17.

- ^ Itzhaq Beit-Arieh (August 1986). "Two Cultures in the Southern Sinai in the Third Millenium BCE". No. 263. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research: 27-54.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Raja G. Mattar (August 2005). "Arab Christians are Arabs". PASSIA. Retrieved 2007-08-18."What used to be known as Bilad Al Sham (Greater Syria, if you will) was Arabized long before Islam. To quote Salibi again (ch. 5): "Since pre-Islamic times, Mount Lebanon appears to have been densely populated by Arab tribes.." In ch. 7: "To maintain that the Syrians came to be [A]rabized after the conquest of their country by the Muslim Arabs was simply not correct, because Syria was already largely inhabited by Arabs—in fact, Christian Arabs—long before Islam."

- ^ Steve Tamari. "Who are the Arabs?" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- ^ Griffith, Sidney H. (1997). "From Aramaic to Arabic: The Languages of the Monasteries of Palestine in the Byzantine and Early Islamic Periods". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 51: 13.

- ^ Kees Versteegh (2001). "The Arabic Language". Edinburgh University. ISBN 0748614362.

- ^ Healey, 2001, pp. 26-28.

- ^ Eph`al I (1984) The Ancient Arabs. The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem

- ^ Marcia Kunstel and Joseph Albright (1990). Their Promised Land: Arab and Jew in History's Cauldron-One Valley in the Jerusalem Hills. Crown. ISBN 0517572311."Between 3000 and 1100 B.C., Canaanite civilization covered what is today Israel, the West Bank, Lebanon and much of Syria and Jordan ... Those who remained in the Jerusalem hills after the Romans expelled the Jews [in the second century A.D.] were a potpourri: farmers and vineyard growers, pagans and converts to Christianity, descendants of the Arabs, Persians, Samaritans, Greeks and old Canaanite tribes."

- ^ Christison, Kathleen. Review of Marcia Kunstel and Joseph Albright's Their Promised Land: Arab and Jew in History's Cauldron-One Valley in the Jerusalem Hills. Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 21, No. 4. (Summer, 1992), pp. 98-100.

- ^ a b Netty C. Gross (11 September 2000). "Demolishing David". The Jerusalem Report: 40.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Michael Balter, "Palestinians Inherit Riches, but Struggle to Make a Mark" Science, New Series, Vol. 287, No. 5450. (Jan. 7, 2000), pp. 33-34. "'We don't want to repeat the mistakes the Israelis made,' says Moain Sadek, head of the Department of Antiquities's operations in the Gaza Strip. Taha agrees: 'All these controversies about historical rights, who came first and who came second, this is all rooted in ideology. It has nothing to do with archaeology.'"

- ^ Bernard Lewis, Semites and Anti-Semites: An Inquiry Into Conflict and Prejudice, W. W. Norton & Company, 1999, ISBN 0393318397, p. 49/

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (October 30, 2000). "Jews and Arabs Share Recent Ancestry". ScienceNOW. American Academy for the Advancement of Science.

- ^ See J1 Haplogroup frequencies in last page: [3]

- ^ Martinez; et al. (31 January 2007). "Paleolithic Y-haplogroup heritage predominates in a Cretan highland plateau". European Journal of Human Genetics.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Semino; et al. (2004). "Origin, Diffusion and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J" (PDF). 74. American Journal of Human Genetics: 1023-1034.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Rita Gonçalves; et al. (July 2005). [www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00161.x "Y-chromosome Lineages from Portugal, Madeira and Açores Record Elements of Sephardim and Berber Ancestry"]. 69, Issue 4. Annals of Human Genetics: 443.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ E. Levy- Coffman (2005). "A Mosaic of People". Journal of Genetic Genealogy: 12-33.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Cinnioglu; et al. (29 October 2003). "Haplogroup J1-M267 typifies East Africans and Arabian populations" (PDF). 114. Human Genetics: 127–148.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ DNA Haplogroup Definitions - J

- ^ Almut Nebel et Al., Genetic Evidence for the Expansion of Arabian Tribes into the Southern Levant and North Africa, Am J Hum Genet. 2002 June; 70(6): 1594–1596[4]

- ^ Eph`al I (1984) The Ancient Arabs. The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem

- ^ Almut Nebel, Ariella Oppenheim, "High-resolution Y chromosome haplotypes of Israeli and Palestinian Arabs reveal geographic substructure and substantial overlap with haplotypes of Jews." Human Genetics 107(6) (December 2000): 630-641

- ^ Judy Siegel,Jerusalem Post (November 20, 2001)

- ^ Nebel et al. 2001, The Y Chromosome Pool of Jews as Part of the Genetic Landscape of the Middle East, Ann Hum Genet. 2001 Mar;70(2):195-206.[5]

References

- Barzilai, Gad. (2003). Communities and Law: Politics and Cultures of Legal Identities. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-11315-1

- Boyle, Kevin and Sheen, Juliet (1997). Freedom of Religion and Belief: A World Report. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415159776

- Cohen, Robin (1995). The Cambridge Survey of World Migration. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521444055

- Drummond, Dorothy Weitz (2004). Holy Land, Whose Land?: Modern Dilemma, Ancient Roots. Fairhurst Press. ISBN 0974823325

- Farsoun, Samih K. (2004). Culture and Customs Of The Palestinians. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313320519

- Guzmán, Roberto Marín (2000). A Century of Palestinian Immigration Into Central America. Editorial Universidad de C.R. ISBN 9977675872

- Healey, John F. (2001). The Religion of the Nabataeans: A Conspectus. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 9004107541

- Howell, Mark (2007). What Did We Do to Deserve This? Palestinian Life under Occupation in the West Bank, Garnet Publishing. ISBN 1859641954

- Khalidi, Rashid (1997). Identity:The Construction of Modern National Consciousness. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231105142. OCLC 35637858. LCCN 96-0 – 0.

- Khalidi, Rashid (2006). The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle for Statehood, Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-8070-0308-5

- Porath, Yehoshua (1974). The Emergence of the Palestinian-Arab National Movement 1918–1929. London: Frank Cass and Co., Ltd. ISBN 0-7146-2939-1

- Porath, Yehoshua (1977). Palestinian Arab National Movement: From Riots to Rebellion: 1929–1939, vol. 2, London: Frank Cass and Co., Ltd.

External links

- BBC: Israel and the Palestinians

- Save the Children: life in a refugee camp

- Guardian Special Report: Israel and the Middle East

- United Nations Programme of Assistance to the Palestinian People

- al-Jazeera: Palestine, the People and the Land

- The Palestine National Charter

- Palestine: Contemporary Art - online magazine articles