Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan is the name of a number of past and present fraternal organizations in the United States that have advocated white supremacy and anti-Semitism; and in the past century, anti-Catholicism, and nativism. These organizations have often promoted the use of terror and violence against African Americans and others, and some of its members have been convicted of murder and manslaughter in the deaths of Civil Rights workers and children.

The Klan's first incarnation was in 1866. Founded by veterans of the Confederate Army, its main purpose was to resist Reconstruction, and it focused as much on intimidating "carpetbaggers" and "scalawags" as on putting down the freed slaves. It quickly adopted violent methods. A rapid reaction set in, with the Klan's leadership disowning it, and Southern elites seeing the Klan as an excuse for federal troops to continue their activities in the South. The organization was in decline from 1868 to 1870, and was destroyed in the early 1870s by President Ulysses S. Grant's vigorous action under the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act).

The founding in 1915 of a second distinct group using the same name was inspired by the newfound power of the modern mass media, via the film The Birth of a Nation and inflammatory and anti-Semitic newspaper accounts surrounding the trial and lynching of accused murderer Leo Frank. The second KKK was a formal membership organization, with a national and state structure, that paid thousands of men to organize local chapters all over the country. Millions joined and at its peak in the 1920s the organization included about 15% of the nation's eligible population.[1] The second KKK typically preached Racism, anti-Catholicism, nativism, and anti-Semitism and some local groups took part in lynchings and other violent activities. Its popularity fell during the Great Depression, and membership fell further during World War II, due to scandals resulting from prominent members' crimes and support of the Nazis.

The name "Ku Klux Klan" has since been used by many different unrelated groups, including many who opposed the Civil Rights Act and desegregation in the 1960s. Today, dozens of organizations with chapters across the United States and other countries use all or part of the name in their titles, but their total membership is estimated to be only a few thousand. These groups, with operations in separated small local units, are considered extreme hate groups. The modern KKK has been disowned by all mainstream media and political and religious leaders.

The first Klan

Creation

The original Ku Klux Klan was created after the end of the American Civil War on December 24 1865, by six educated, middle-class Confederate veterans[2] who were bored with postwar life in Pulaski, Tennessee. The name was constructed by combining the Greek "kyklos" (circle) with "clan."[3] It was at first a humorous social club centering on practical jokes and hazing rituals.[4] From 1866 to 1867, the Klan began breaking up black prayer meetings and invading black homes at night to steal firearms. Some of these activities may have been modeled on previous Tennessee vigilante groups such as the Yellow Jackets and Redcaps.

"Founded in 1866 as a Tennessee social club, the Ku Klux Klan now spread into nearly every Southern state, launching a "reign of terror" against Republican leaders black and white. Those assassinated during the campaign included Arkansas Congressman James M. Hinds, three members of the South Carolina legislature, and several men who had served in constitutional conventions." (Foner,Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 p. 342)

In an 1867 meeting in Nashville an effort was made to create a hierarchical organization with local chapters reporting to county leaders, counties reporting to districts, districts reporting to states, and states reporting to a national headquarters. The proposals, in a document called the "Prescript," were written by George Gordon, a former Confederate brigadier general. The Prescript included inspirational language about the goals of the Klan along with a list of questions to be asked of applicants for membership, which confirmed the focus on resisting Reconstruction and the Republican Party. The applicant was to be asked whether he was a Republican, a Union Army veteran, or a member of the Loyal League; whether he was "opposed to Negro equality both social and political;" and whether he was in favor of "a white man's government," "maintaining the constitutional rights of the South," "the reenfranchisement and emancipation of the white men of the South, and the restitution of the Southern people to all their rights," and "the inalienable right of self-preservation of the people against the exercise of arbitrary and unlicensed power."

Despite the work that came out of the 1867 meeting, the Prescript was never accepted by any of the local units. They continued to operate autonomously, and there never were county, district or state headquarters.

According to one oral report, Gordon went to former slave trader and Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest in Memphis and told him about the new organization, to which Forrest replied, "That's a good thing; that's a damn good thing. We can use that to keep the niggers in their place."[5] A few weeks later, Forrest was selected as Grand Wizard, the Klan's national leader. In later interviews, however, Forrest denied the leadership role and stated that he never had any effective control over the Klan cells.

Activities

The Klan sought to control the political and social status of the freed slaves. Specifically, it attempted to curb black education, economic advancement, voting rights, and the right to bear arms. However, the Klan's focus was not limited to African Americans. Southern Republicans also became the target of vicious intimidation tactics. The violence achieved its purpose. For example, in the April, 1868 Georgia gubernatorial election, Columbia County cast 1222 votes for Democrat Rufus Bullock, but in the November presidential election, the county cast only one vote for Republican candidate Ulysses Grant.[6]

Klan intimidation was often targeted at schoolteachers and operatives of the federal Freedmen's Bureau. Black members of the Loyal Leagues were also the frequent targets of Klan raids. In a typical episode in Mississippi, according to the Congressional inquiry [7]

One of these teachers (Miss Allen of Illinois), whose school was at Cotton Gin Port in Monroe County, was visited ... between one and two o'clock at night in March, 1871, by about fifty men mounted and disguised. Each man wore a long white robe and his face was covered by a loose mask with scarlet stripes. She was ordered to get up and dress which she did at once and then admitted to her room the captain and lieutenant who in addition to the usual disguise had long horns on their heads and a sort of device in front. The lieutenant had a pistol in his hand and he and the captain sat down while eight or ten men stood inside the door and the porch was full. They treated her "gentlemanly and quietly" but complained of the heavy school-tax, said she must stop teaching and go away and warned her that they never gave a second notice. She heeded the warning and left the county.

An 1868 proclamation by Gordon[8] demonstrates several of the issues surrounding the Klan's violent activities.

- Many blacks were veterans of the Union Army, and were armed. From the beginning, one of the original Klan's strongest focuses was on confiscating firearms from Blacks. In the proclamation, Gordon warned that the Klan had been "fired into three times," and that if the blacks "make war upon us they must abide by the awful retribution that will follow." The Klan had no objections to whites being armed.

- Gordon also stated that the Klan was a peaceful organization. Such claims were common ways for the Klan to attempt to protect itself from prosecution. However, a federal grand jury in 1869 determined that the Klan was a "terrorist organization." Hundreds of indictments for crimes of violence and terrorism were issued. Klan members were prosecuted, and many fled jurisdiction, particularly in South Carolina. (Trelease, Allen W., White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction)

- Gordon warned that some people had been carrying out violent acts in the name of the Klan. It was true that many people who had not been formally inducted into the Klan found the Klan's uniform to be a convenient way to hide their identities when carrying out acts of violence. However, it was also convenient for the higher levels of the organization to disclaim responsibility for such acts, and the secretive, decentralized nature of the Klan made membership fuzzy rather than clear-cut.

"One should not think of the Klan, even in its hey day, as possessing a well-organized structure or clearly defined regional leadership. Acts of violence were generally committed by local groups on their own initiative. But the unity of purpose and common tactics of these local organizations makes it possible to generalize about their goals and impact, and the challenge they posed to the survival of Reconstruction. In effect, the Klan was a military force serving the interests of the Democratic party, the planter class, and all those who desired the restoration of white supremacy. Its purposes were political, but political in the broadest sense, for it sought to affect power relations, both public and private, throughout Southern Society. It aimed to reverse the interlocking changes sweeping over the South during Reconstruction: to destroy the Republican party's infrastructure, undermine the Reconstruction state, reestablish control of the black labor force, and restore racial subordination in every aspect of Southern life." (Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, p. 426)

On pages 425-444 and 454-459, Foner quotes from testimony at the federal KKK Hearings in Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, South Carolina, North Carolina and Georgia, and other primary sources to describe widespread terror and extraordinary brutality, including rape and murder by Klan members that led to the passage of the Ku Klux Klan Act. Foner wrote also (p. 435) of the resistance to Klan terror. "Occasionally, organized groups successfully confronted the Klan. White Union Army veterans in mountainous Blount County, Alabama, organized "the anti-Ku Klux," which put an end to violence by threatening Klansmen with reprisals unless they stopped whipping Unionists and burning black churches and schools. Armed blacks patrolled the streets of Bennettsville, South Carolina, to prevent Klan assaults."

By this time, only two years after the Klan's creation, its activity was already beginning to decrease[9] and, as Gordon's proclamation shows, to become less political and more simply a way of avoiding prosecution for violence. Many influential southern Democrats were beginning to see it as a liability, an excuse for the federal government to retain its power over the South.[10] Georgian B.H. Hill went so far as to claim "that some of these outrages were actually perpetrated by the political friends of the parties slain."[11]

But "the bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era was the Colfax massacre which began when black citizens fought back against the Klan and its allies in the White league. "Louisiana black teacher and legislator John G. Lewis later remarked. "They attempted (armed self-defense) in Colfax. The result was that on Easter Sunday of 1873, when the sun went down that night, it went down on the corpses of two hundred and eighty negroes." (Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, p. 437) and KKK Hearings, 46th Congress, 2d Session, Senate Report 693, and Joe G. Taylor, Louisiana Reconstructed, 1863-1877 (Baton Rouge, 1974), p. 268-70.)

In an 1868 newspaper interview,[12] Forrest boasted that the Klan was a nationwide organization of 550,000 men, and that although he himself was not a member, he was "in sympathy" and would "cooperate" with them, and could himself muster 40,000 Klansmen with five days' notice. He stated that the Klan did not see blacks as its enemy so much the Loyal Leagues, Republican state governments like Tennessee governor Brownlow's, and other carpetbaggers and scalawags. There was an element of truth to this claim, since the Klan did go after white members of these groups, especially the schoolteachers brought south by the Freedmen's Bureau, many of whom had before the war been abolitionists or active in the underground railroad. Many white southerners believed, for example, that blacks were voting for the Republican Party only because they had been hoodwinked by the Loyal Leagues. Black members of the Loyal Leagues were also the frequent targets of Klan raids. One Alabama newspaper editor declared that "The League is nothing more than a nigger Ku Klux Klan."[13]

Decline and suppression

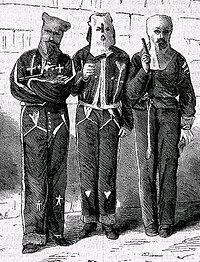

The first Klan was never well organized. As a secret or "invisible" group, it had no membership rosters, no dues, no newspapers, no spokesmen, no chapters, no local officers, no state or national officials. Its popularity came from its reputation, which was greatly enhanced by its outlandish costumes and its wild and threatening theatrics. As historian Elaine Frantz Parsons discovered [14]:

"Lifting the Klan mask revealed a chaotic multitude of antiblack vigilante groups, disgruntled poor white farmers, wartime guerrilla bands, displaced Democratic politicians, illegal whiskey distillers, coercive moral reformers, bored young men, sadists, rapists, white workmen fearful of black competition, employers trying to enforce labor discipline, common thieves, neighbors with decades-old grudges, and even a few freedmen and white Republicans who allied with Democratic whites or had criminal agendas of their own. Indeed, all they had in common, besides being overwhelmingly white, southern, and Democratic, was that they called themselves, or were called, Klansmen."

Forrest's national organization had little control over the local autonomous Klans. One Klan official complained that his own "so-called 'Chief'-ship was purely nominal, I having not the least authority over the reckless young country boys who were most active in 'night-riding,' whipping, etc., all of which was outside of the intent and constitution of the Klan..." Forrest ordered the Klan to disband in 1869, stating that it was "being perverted from its original honorable and patriotic purposes, becoming injurious instead of subservient to the public peace."[15] Due to the national organization's lack of control, this proclamation was more a symptom of the Klan's decline than a cause of it. Journalist Stanley Horn writes that "generally speaking, the Klan's end was more in the form of spotty, slow, and gradual disintegration than a formal and decisive disbandment."[16] A reporter in Georgia wrote in January 1870 that "A true statement of the case is not that the Ku Klux are an organized band of licensed criminals, but that men who commit crimes call themselves Ku Klux."[17]

During Reconstruction, Klansmen killed more than 150 African Americans in a single county in Florida, and hundreds more in other counties.(The Invisible Empire: The Ku Klux Klan in Florida, by Michael Newton) (pp.1-30) Newton quotes from the Testimony Taken by the Joint Select Committee to Enquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States. Vol. 13. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1872). Among historians of the Klan, this volume is also known as "The KKK testimony."

Although the Klan was being used more and more often as a mask for nonpolitical crimes, state and local governments seldom acted against it. In lynching cases, whites were almost never indicted by all-white coroner's juries, and even when there was an indictment, all-white trial juries were extremely unlikely to vote for conviction. In many states, there were fears that the use of black militiamen would ignite a race war.[18] When Republican governor Holden of North Carolina called out the militia against the Klan in 1870, the result was a backlash that lost him the upcoming election.[19]

Meanwhile, many Democrats at the national level were questioning whether the Klan even existed, or was a creation of nervous Republican governors in the South.[20] In January 1871, Pennsylvania Republican senator John Scott convened a committee which took testimony from 52 witnesses about Klan atrocities. Many Southern states had already passed anti-Klan legislation, and in February former Union general Benjamin Franklin Butler of Massachusetts (who was widely reviled by Southern whites) introduced federal legislation modeled on it.[21] The tide was turned in favor of the bill by the governor of South Carolina's appeal for federal troops, and by reports of a riot and massacre in a Meridian, Mississippi courthouse, which a black state representative escaped only by taking to the woods.[22]

In 1871 President Ulysses S. Grant signed Butler's legislation, the Ku Klux Klan Act, which was used along with the 1870 Force Act to enforce the civil rights provisions of the constitution. Under the Klan Act, federal troops were used rather than state militias, and Klansmen were prosecuted in federal court, where juries were often predominantly black.[23] Hundreds of Klan members were fined or imprisoned, and habeas corpus was suspended in nine counties in South Carolina. These efforts were so successful that the Klan was destroyed in South Carolina[24] and decimated throughout the rest of the country, where it had already been in decline for several years. Prosecutions were led by Attorney General Amos Tappan Ackerman. The tapering off of the federal government's actions under the Klan Act, ca. 1871–74, went along with the final extinction of the Klan,[25] although in some areas similar activities, including intimidation and murder of black voters, continued under the auspices of local organizations such the White League, Red Shirts, saber clubs, and rifle clubs.[26] Even though the Klan no longer existed, it had achieved many of its goals, such as denying voting rights to Southern blacks.

In 1882, long after the end of the first Klan, the Supreme Court ruled in United States vs. Harris that the Klan Act was partially unconstitutional, saying that Congress's power under the fourteenth amendment did not extend to private conspiracies.[27] However, the Force Act and the Klan Act have been invoked in later civil rights conflicts, including the 1964 murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner[28]; the 1965 murder of Viola Liuzzo;[29] and Bray vs. Alexandria Women's Health Clinic, 1991, which became an issue in the 2005 debate on the confirmation of John G. Roberts, Jr.'s nomination to the Supreme Court.[30]

The second Klan

Creation

The founding of the second Ku Klux Klan in 1915 demonstrated the newfound power of modern mass media. The year saw three closely related events:

- The film The Birth of a Nation was released, mythologizing and glorifying the first Klan.

- Leo Frank, a Jewish man accused of the rape and murder of a young white girl named Mary Phagan, was lynched against a backdrop of media frenzy.

- The second Ku Klux Klan was founded with a new anti-immigrant and anti-Semitic agenda. The bulk of the founders were from an organization calling itself the Knights of Mary Phagan, and the new organization emulated the fictionalized version of the original Klan presented in The Birth of a Nation.

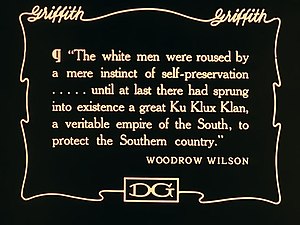

D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation glorified the original Klan, which was by then a fading memory. Griffith's film was based on the fictional account, a novel and play The Clansman and the book The Leopard's Spots: A Romance of The White Man's Burden, both by Thomas Dixon who said his purpose was "to revolutionize northern sentiment by a presentation of history that would transform every man in my audience into a good Democrat!" The film created a nationwide craze among some white people for the Klan. At a preview in Los Angeles, actors dressed as Klansmen were hired to ride by as a promotional stunt, and real-life members of the newly reorganized Klan rode up and down the street at its later official premiere in Atlanta. In some cases, enthusiastic southern audiences fired their guns into the screen.[31] The film's popularity and influence were enhanced by a widely reported endorsement of its factual accuracy by historian and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson (see below, under Political Influence) as a favor to an old friend. Much of the modern Klan's iconography, including the standardized white costume and the burning cross, are imitations of the film, whose imagery was itself based on Dixon's romanticized concept of old Scotland as portrayed in the novels and poetry of Sir Walter Scott rather than on the Reconstruction Klan.

The Birth of a Nation includes extensive quotations from Woodrow Wilson's History of the American People,[32] e.g., "The white men were roused by a mere instinct of self-preservation ... until at last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan, a veritable empire of the South, to protect the Southern country." Wilson, on seeing the film in a special White House screening on February 18, 1915, exclaimed, "It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true."[33] Wilson's family had sympathized with the Confederacy during the Civil War, and cared for wounded Confederate soldiers at a church. When he was a young man, his party had vigorously opposed Reconstruction, and as president he resegregated the federal government for the first time since Reconstruction. Given the film's strong Democratic partisan message and Wilson's documented views on race and the Klan, it is not unreasonable to interpret the statement as supporting the Klan, and the word "regret" as referring to the film's depiction of Radical Republican Reconstruction. Later correspondence with the film's director, D.W. Griffith, confirms Wilson's enthusiasm about the film. Wilson's remarks were widely reported and immediately became controversial. Wilson tried to remain aloof from the controversy, but finally, on April 30, he issued a non-denial denial.[34] His endorsement of the film greatly enhanced its popularity and influence, and helped Griffith to defend it against legal attack by the NAACP; the film, in turn, was a major factor leading to the creation of the second Klan in the same year.

In the same year, an important event in the coalescence of the second Klan was the lynching of Leo Frank, a Jewish factory manager. In sensationalistic newspaper accounts, Frank was accused of fantastic sexual crimes and of the murder of a Mary Phagan, a girl employed at his factory. He was convicted of murder after a questionable trial in Georgia (the judge asked that Frank and his counsel not be present when the verdict was announced due to the violent mob of people surrounding the court house). His appeals failed (Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes dissented, condemning the intimidation of the jury as failing to provide due process of law). The governor then commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, but a mob calling itself the Knights of Mary Phagan kidnapped Frank from the prison farm and lynched him. Ironically, much of the evidence in the murder actually pointed to the factory's black janitor, Jim Conley, who the prosecution claimed only helped Frank to dispose of the body.

For many southerners who believed Frank to be guilty, there was a strong resonance between the Frank trial and The Birth of a Nation, because they saw an analogy between Mary Phagan and the film's character Flora, a young virgin who throws herself off a cliff to avoid being raped by the black character Gus, described as "a renegade, a product of the vicious doctrines spread by the carpetbaggers."

The Frank trial was used skillfully by Georgia politician and publisher Thomas E. Watson, the editor for The Jeffersonian magazine at the time and later a leader in the reorganization of the Klan who was later elected to the U.S. Senate. The new Klan was inaugurated in 1915 at a mountaintop meeting led by William J. Simmons and attended by aging members of the original Klan, along with members of the Knights of Mary Phagan.

Simmons found inspiration for this second Klan in the original Klan's "Prescripts," written in 1867 by George Gordon (a former Confederate brigadier general) in an attempt to give the original Klan a sense of national organization. [35] The Prescript states as the Klan's purposes:[36]

- First: To protect the weak, the innocent, and the defenseless from the indignities, wrongs and outrages of the lawless, the violent and the brutal; to relieve the injured and oppressed; to succor the suffering and unfortunate, and especially the widows and orphans of the Confederate soldiers.

- Second: To protect and defend the Constitution of the United States ...

- Third: To aid and assist in the execution of all constitutional laws, and to protect the people from unlawful seizure, and from trial except by their peers in conformity with the laws of the land.

Despite the noble rhetoric, Klan members lynched and burned to death veterans returning from World War I. American historian John Hope Franklin wrote in his book Race and History: Selected Essays 1938-1988 (p. 145) that "Few Negro Americans could have anticipated the wholeseale rejection they experienced at the conclusion of World War I. Returning Negro soldiers were lynched by hanging and burning, even while still in their military uniforms. The Klan warned Negroes that they must respect the rights of the white race "in whose country they are permitted to reside.""

Membership

Historians in recent years have obtained membership rosters of some local units and matched the names against city directory and local records to create statistical profiles of the membership. Big city newspapers were unanimously hostile and often ridiculed the Klansmen as ignorant farmers. Detailed analysis from Indiana [37] shows the stereotype was false:

Indiana's Klansmen represented a wide cross section of society: they were not disproportionately urban or rural, nor were they significantly more or less likely than other members of society to be from the working class, middle class, or professional ranks. Klansmen were Protestants, of course, but they cannot be described exclusively or even predominately as fundamentalists. In reality, their religious affiliations mirrored the whole of white Protestant society, including those who did not belong to any church.

The Klan was successful in recruiting throughout the country and in Canada, but the membership turned over rapidly. Since the Klan was a secret society, it is difficult to determine accurate membership numbers.

This Klan was operated as a profit-making venture by its leaders, and participated in the boom in fraternal organizations at the time. Organizers signed up hundreds of new members, who paid initiation fees and bought KKK costumes. The organizer kept half the money and sent the rest to state or national officials. When the organizer was done with an area, he organized a huge rally, often with burning crosses and perhaps a ceremonial presentation of a Bible to a local Protestant minister. He left town with all the money. The local units operated like many fraternal organizations, occasionally bringing in speakers. The state and national officials had little or no control over the locals and rarely or never attempted to forge them into political activist groups.

Activities

In keeping with its origins in the Leo Frank lynching, the reorganized Klan had a new anti-Jewish, anti-Catholic, and anti-immigrant slant. This was consistent with the new Klan's greater success at recruiting in the U.S. Midwest than in the South. As in the Nazi party's propaganda in Germany, recruiters made effective use of the idea that prospective members' problems were caused by Blacks or by Jewish bankers, or by other such groups.

The Ragen Colts, an Irish street gang in Chicago, directed its anger at the Ku Klux Klan for its anti-Catholicism. In 1921, "In September, 3,000 people from the stockyards district (of Chicago) watched as the Colts hanged in effigy "a white-sheeted Klansman."" (Tuttle, p. 257)

In the 1920s and 1930s a faction of the Klan called the Black Legion was very active in the Midwestern U.S. Rather than wearing white robes, the Legion wore black uniforms reminiscent of pirates. The Black Legion was the most violent and zealous faction of the Klan, and were notable for targeting and assassinating communists and socialists.

This Klan was operated as a profit-making venture by its leaders, and participated in the boom in fraternal organizations at the time. It differed from the first Klan. The first Klan was Democratic and Southern, but this Klan, while it still boasted members from the Democratic Party, was to a greater degree Republican and was influential throughout the United States, with major political influence on politicians in several states.

Political influence

The second Ku Klux Klan rose to great prominence and spread from the South into the Midwest region and Northern states and even into Canada. At its peak, Klan membership exceeded 4 million and comprised 20% of the adult white male population in many broad geographic regions, as high as 40% in some areas. Most of the membership resided in Midwestern states.

Through sympathetic elected officials, the KKK controlled the governments of Tennessee, Indiana, Oklahoma, and Oregon in addition to some of the Southern legislatures. Klan influence was particularly strong in Indiana, where Republican Klansman Edward Jackson was elected governor in 1924, and the entire apparatus of state government was riddled with Klansmen. In another well-known example from the same year, the Klan decided to make Anaheim, California, into a model Klan city; it secretly took over the city council, but was voted out in a special recall election.

Klan delegates played a significant role at the pathsetting 1924 Democratic National Convention in New York City, often called the "Klanbake Convention" as a result. The convention initially pitted Klan-backed candidate William McAdoo against New York Governor Al Smith, who drew the opposition of the group because of his Catholic faith. After days of stalemates and rioting, both candidates withdrew in favor of a compromise. Klan delegates defeated a Democratic Party platform plank that would have condemned their organization. On July 4, 1924, thousands of Klansmen converged on a nearby field in New Jersey where they participated in cross burnings, burned effigies of Smith, and celebrated their defeat of the platform plank.

There is also evidence that in certain states, such as Alabama, the KKK was not a mere hate group and showed a genuine desire for political and social reform.[38] Because of the elite conservative political structure in Alabama, the state's Klansmen were among the foremost advocates of better public schools, effective prohibition enforcement, expanded road construction, and other "progressive" political measures. In many ways these progressive political goals, which benefited ordinary and lower class white people in the state, were the result of the Klan offering these same people their first chance to install their own political champions into office. [39]

By 1925 the Klan was a powerful political force in the state, as powerful figures like J. Thomas Heflin, David Bibb Graves, and Hugo Black manipulated the KKK membership against the power of the "Big Mule" industrialists and Black Belt planters who had long dominated the state. Black was elected Senator in 1926 and became a leading supported of the New Deal. Appointed to the Supreme Court in 1937, revelation that he was a former Klansman shocked the country but he stayed on the Court. In 1926 Bibb Graves, a former chapter head, won the governor's office with KKK members' support. He led one of the most progressive administrations in the state's history, pushing for increased education funding, better public health, new highway construction, and pro-labor legislation.

However, as a result of these political victories, KKK vigilantes, thinking they enjoyed governmental protection, launched a wave of physical terror across Alabama in 1927, targeting both blacks and whites. The Klan not only targeted people for violating racial norms but also for perceived moral lapses. In Birmingham, the Klan raided local brothels and roadhouses. In Troy, Alabama, the Klan reported to parents the names of teenagers they caught making out in cars. One local Klan group even "kidnapped a white divorcee and stripped her to her waist, tied her to a tree, and whipped her savagely." [40] The conservative elite counterattacked. Grover C. Hall, Sr., editor of the Montgomery Advertiser, began a series of editorials and articles attacking the Klan for their "racial and religious intolerance." Hall ended up winning a Pulitzer Prize for his crusade.[41] Other newspapers also kept up a steady, loud attack on the Klan as violent and un-American. Sheriffs cracked down on Klan violence. The counterattack worked; the state voted for Catholic Al Smith for president in 1928, and the Klan's official membership in Alabama plunged to under six thousand by 1930.

At the peak of the Klan's political power, a number of highly notable political figures in the U.S. and Canada joined the Klan or flirted with membership. The list includes two Supreme Court justices and, according to evidence which is in some cases contested, possibly two presidents.

- Main article: Notable Ku Klux Klan members in national politics

Decline

The second Klan collapsed partly as a result of the backlash to their actions and partly as a result of a scandal involving Republican David Stephenson, the Grand Dragon of Indiana and fourteen other states, who was convicted of the rape and murder of Madge Oberholtzer in a sensational trial (she was bitten so many times that one man who saw her described her condition as having been "chewed by a cannibal"). According to historian Leonard Moore, at the heart of the backlash to the Klan's actions and the resulting scandals was a leadership failure which caused the organization's collapse: [42]

Stephenson and the other salesmen and office seekers who maneuvered for control of Indiana's Invisible Empire lacked both the ability and the desire to use the political system to carry out the Klan's stated goals. They were disinterested in, or perhaps even unaware of, grass roots concerns within the movement. For them, the Klan had been nothing more than a means for gaining wealth and power. These marginal men had risen to the top of the hooded order because, until it became a political force, the Klan had never required strong, dedicated leadership. More established and experienced politicians who endorsed the Klan, or who pursued some of the interests of their Klan constituents, also accomplished little. Factionalism created one barrier, but many politicians had supported the Klan simply out of expedience. When charges of crime and corruption began to taint the movement, those concerned about their political futures had even less reason to work on the Klan's behalf.

As a result of these scandals, the Klan fell out of public favor in the 1930s and withdrew from political activity. Grand Wizard Hiram Evans sold the organization in 1939 to James Colescott, an Indiana veterinarian, and Samuel Green, an Atlanta obstetrician, but they were unable to staunch the exodus of members. The Klan's image was further damaged by Colescott's association with Nazi-sympathizer organizations, the Klan's involvement with the 1943 Detroit Race Riot, and efforts to disrupt the American war effort during World War II. In 1944 the IRS filed a lien for $685,000 in back taxes against the Klan, and Colescott was forced to dissolve the organization in 1944.

The name Ku Klux Klan then began to be used by a number of independent groups. The following table shows the decline in the Klan's estimated membership over time.[43] (The years given in the table represent approximate time periods.)

| year | membership |

| 1920 | 4,000,000 |

| 1930 | 30,000 |

| 1970 | 2,000 |

| 2000 | 3,000 |

Folklorist and author Stetson Kennedy infiltrated the Klan after World War II and provided information on the Klan to media and law enforcement agencies. He also provided Klan information, including secret code words, to the writers of the Superman radio program, resulting in a series of four episodes in which Superman took on the KKK. Kennedy intended to strip away the Klan's mystique and the trivialization of the Klan's rituals and code words likely did have a negative impact on Klan recruiting and membership.[44] Kennedy eventually wrote a book based on his experiences, which became a bestseller during the 1950s and further damaged the Klan. [45]

Later Ku Klux Klans

While people had always fought back against the Klan, after World War II the Klan's foes began to gain an upper hand. In a 1958 North Carolina incident, the Klan burned crosses at the homes of two Lumbee Native Americans who had associated with white people, and then held a nighttime rally nearby, only to find themselves surrounded by hundreds of armed Lumbees. Gunfire was exchanged, and the Klan was routed.[46]

The criminal history of Klan members has been better documented in recent years than previously, and its members have been sent to prison for murder and manslaughter in the deaths of civil rights workers. Here is an incomplete list.

- Murder conviction of former Ku Klux Klansman Byron de la Beckwith in 1994 for the 1963 assassination of NAACP organizer Medgar Evers in Mississippi.

- Murder conviction of former Ku Klux Klan wizard Sam Bowers in 1998 for the 1966 firebombing death of NAACP leader Vernon Dahmer Sr., 58, also in Mississippi. Two other Klan members were indicted with Bowers, but one died before trial, and the other's indictment was dismissed.[2]

- Four Klansmen were named as suspects in the killing four children, Denise McNair, 11, Cynthia Wesley, 14, Carole Robertson, 14, and Addie Mae Collins, 14, on Sept. 15, 1963 in Birmingham, Alabama. but the Klansmen were not prosecuted until years later. The Klan members were Robert Chambliss, convicted in 1977, Thomas Blanton and Bobby Frank Cherry, convicted of murder in 2001 and 2002. The fourth suspect, Herman Cash, died before he was indicted.

- Willie Edwards, Jr. (1932 - 1957). Forced by Klansmen to jump to his death from a bridge into the Alabama River. [3]

- Charles Eddie Moore (1944 - 1964). Killed by Klan. [4]

- Henry Hezekiah Dee (1945 - 1964). Killed by Klan. [5]

- In June 2005, Klan member Edgar Ray Killen was convicted of manslaughter in the 1964 murder in Philadelphia, Miss. of three civil rights workers, Michael Schwerner, 25, Andrew Goodman, 21, and James Chaney, 21.[6][7][8]

- Viola Gregg Liuzzo (1925 - 1965). Killed by Klan while transporting Civil Rights Marchers. [9]

- Ben Chester White (1899 - 1966). Killed by Klan. [10]

The postwar Klan resisted the civil rights movement during the 1960s. In 1963, two Klan members carried out the bombing of a church in Alabama that had been used as a meeting place for civil rights organizers. Four young girls were killed, and outrage over the bombing helped to build momentum for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. [[Folk singer Joan Baez popularized a song, called Birmingham Sunday about the children's murders. The Klan used threats, intimidation, and murder to disrupt voter registration drives in the South, and to prevent registered black voters from voting. In 1964, Klan members murdered civil rights workers Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in Mississippi, and also murdered Viola Liuzzo, a Southern-raised white mother of five who was visiting the South from her home in Detroit to attend a civil rights march.

In 1964, the FBI's COINTELPRO program began attempts to infiltrate and disrupt the Klan. COINTELPRO occupied a curiously ambiguous position in the civil rights movement, since it used its tactics of infiltration, disinformation, and violence against violent far-left and far-right groups such as the Klan and the Weathermen, but simultaneously against peaceful organizations such as Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. This ambivalence was shown dramatically in the case of the murder of Liuzzo, who was shot on the road by four Klansmen in a car, of whom one was an FBI informant. After she was murdered, the FBI spread false rumors that she was a communist, and that she had abandoned her children in order to have sex with black civil rights workers. Regardless of the FBI's role, Jerry Thompson, a newspaper reporter who infiltrated the Klan in 1979, reported that COINTELPRO's efforts had been successful in disrupting the Klan. Rival Klan factions both accused each other's leaders of being FBI informants, and one leader, Bill Wilkinson of the Invisible Empire, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, was revealed to have been working for the FBI.[47]

Once the century-long struggle over black voting rights in the South had ended, the Klans shifted their focus to other issues, including affirmative action, immigration, and especially busing ordered by the courts in order to desegregate schools. In 1971, Klansmen used bombs to destroy ten school buses in Pontiac, Michigan, and charismatic Klansman David Duke was active in South Boston during the school busing crisis of 1974. Duke also made efforts to update its image, urging Klansmen to "get out of the cow pasture and into hotel meeting rooms." Duke was leader of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan from 1974 until he resigned in 1978. In 1980, he formed the National Association for the Advancement of White People, a far-right white nationalist political organization. He was elected to the Louisiana State House of Representatives in 1989 as a Republican, even though the party threw its support to a different Republican candidate.

In this period, resistance to the Klan became more common. Thompson reported that in his brief membership in the Klan, his truck was shot at, he was yelled at by black children, and a Klan rally that he attended turned into a riot when black soldiers on an adjacent military base taunted the Klansmen. Attempts by the Klan to march were often met with counterprotests, and violence sometimes ensued.

Michael Donald, 20, was the victim in 1981 of a lynching by Klan members Henry Hays and James "Tiger" Knowles. Hays was executed in the electric chair June 6, 1997 for the murder, and Knowles received a life sentence for testifying against Hays. The Associated Press reported that prosecutors said the slaying was ordered by Klan leaders, including Hays' father, "to show Klan strength in Alabama." The case successfully bankrupted one Klan group.

The Southern Poverty Law Center successfully sued the United Klans of America on behalf of Michael Donald's mother. The $7 million legal victory bankrupted the United Klans of America, which turned over the keys to its building to Mrs. Donald.

"Instead of emboldening racists, the slaying wound up financially destroying the United Klans of America in 1987," AP reported. "The Klan had nowhere near that amount in assets. It had to sign over its Tuscaloosa building to Donald's mother, Beulah Mae Donald, who sold it for about $52,000 and bought a house. She has since died," the AP reported on June 5, 1997.

This encouraged a trend toward the decentralization and retreat of the Klan in the late 20th century, the AP reported. The lawsuit was also mentioned by a British publication [48] in the context of how lawsuits against the Klan were tending to slow them down.

Thompson related how many Klan leaders who appeared indifferent to the threat of arrest showed great concern about a series of multimillion-dollar lawsuits brought against them as individuals by the Southern Poverty Law Center as a result of a shootout between Klansmen and a group of African Americans, and curtailed their activities in order to conserve money for defense against the suits. Lawsuits were also used as tools by the Klan, however, and the paperback publication of Thompson's book was canceled because of a libel suit brought by the Klan.

Klan activity has also been diverted into other racist groups and movements, such as Christian Identity, neo-Nazi groups, and racist subgroups of the skinheads.

Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

"Knights of the Ku Klux Klan" has been part of the title of at least ten organizations patterned on the original KKK. The most prominent of these was the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, Inc., which was founded in November 1915 by William J. Simmons and disbanded in 1944 by James Colescott. At its peak this fraternal organisation had around three to five million members.

In 2005 the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (Knights Party) is headed by National Director Pastor Thom Robb, and based in Harrison, Arkansas. It is the biggest Klan organization in America today. It refers to itself as the "sixth era Klan" and continues to be a racist group.

Robb's group in the past produced such Klan stars as David Duke, but it is now continuing a long, slow decline. In 1991 Thom Robb said that he foresaw imminent respectability for the Klan: "You take Exxon. They had an identity thing to overcome after that oil spill. Well, the Klan has an image problem to overcome, also."

The Ku Klux Klan today

Although often still discussed in contemporary American politics as representing the quintessential "fringe" end of the far-right spectrum, today the group only exists in the form of a number of very isolated, scattered "supporters" that probably do not number more than a few thousand. In a 2002 report on "Extremism in America", the Jewish Anti-Defamation League wrote "Today, there is no such thing as the Ku Klux Klan. Fragmentation, decentralization and decline have continued unabated." However, they also noted that the "need for justification runs deep in the disaffected and is unlikely to disappear, regardless of how low the Klan's fortunes eventually sink."

Today the only known former member of the Klan to hold a Federal office in the United States is Democratic Senator Robert Byrd, who says he "deeply regrets" joining the Klan over half a century ago, when he was about 24 years old. There are currently no known members of the Klan who also hold a Federal office.

Some of the larger KKK organizations currently in operation include:

- Church of the American Knights of the Ku Klux Klan[49]

- Imperial Klans of America

- Knights of the White Kamelia

There is a vast number of smaller organizations.[50]

As of 2005, there were an estimated 3,000 Klan members, divided among 158 chapters of a variety of splinter organizations, about two-thirds of which were in former Confederate states. The other third are primarily in the Midwest region. [51][52][53]

The ACLU has provided legal support to various factions of the KKK in defense of their First Amendment rights to hold public rallies, parades, and marches, and their right to field political candidates.

In a July 2005 incident, a Hispanic man's house was burned down in Hamilton, Ohio, after accusations that he sexually assaulted a nine-year-old white girl. Klan members in Klan robes showed up afterward to distribute pamphlets. In May 2006, a Ku Klux Klan group led an anti-immigration march in Russellville, Alabama.[54]

Ku Klux Klan vocabulary

Membership in the Klan is secret, and the Klan, like many fraternal organizations, has signs members can use to recognize one another. A member may use the acronym AYAK (Are you a Klansman?) in conversation to surreptitiously identify himself to another potential member. The response AKIA (A Klansman I am) completes the greeting.

Throughout its varied history, the Klan has coined many words [55] beginning with "KL" including:

- Klabee: treasurers

- Kleagle: recruiter

- Klecktoken: initiation fee

- Kligrapp: secretary

- Klonvocation: gathering

- Kloran: ritual book

- Kloreroe: delegate

- Kludd: chaplain

See also

- Jim Crow laws

- Silent Brotherhood

- Neo-Nazism

- History of the United States (1865-1918)

- Wide Awakes

- Knights of the Golden Circle

- American Protective Association

- Ku Klux Klan regalia and insignia

- Robert Byrd

- David Duke

Notes

- ^ According to the 1920 census, the population of white males 18 years and older was about 31 million, but many of these men would have been ineligible for membership because they were immigrants, Jews, or Roman Catholics. Klan membership peaked at about 4-5 million: http://www.aaregistry.com/african_american_history/2207/The_Ku_Klux_Klan_a_brief__biography, retrieved August 26, 2005.

- ^ Horn, 1939, p. 9. The founders were John C. Lester, John B. Kennedy, James R. Crowe, Frank O. McCord, Richard R. Reed, and J. Calvin Jones.

- ^ Horn, 1939, p. 11, states that Reed proposed "??????" ("kyklos") and Kennedy added "clan." Wade, 1987, p. 33 says Kennedy came up with both words, but Crowe suggested transforming "??????" into "kuklux."

- ^ Wade, 1987.

- ^ Horn, 1939. Horn casts doubt on some other aspects of the story.

- ^ http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-694, retrieved August 26, 2005.

- ^ History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896. Volume: 7. by James Ford Rhodes, 1920, pages 157-8

- ^ Horn, 1939.

- ^ Horn, 1939, p. 375.

- ^ Wade, 1987, p. 102.

- ^ Horn, 1939, p. 375.

- ^ Cincinnati 'Commercial', August 28, 1868, quoted in Wade, 1987. Full text of the interview on wikisource.

- ^ Horn, 1939, p. 27.

- ^ Parsons, Elaine Frantz, "Midnight Rangers: Costume and Performance in the Reconstruction-Era Ku Klux Klan." The Journal of American History 92.3, 2005, page 816

- ^ quotes from Wade, 1987.

- ^ Horn, 1939, p. 360.

- ^ Horn, 1939, p. 362.

- ^ http://www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/stories_events_enforce.html, retrieved August 11, 2005.

- ^ Wade, 1987, p. 85.

- ^ Wade, 1987.

- ^ Horn, 1939, p. 373.

- ^ Wade, 1987, p. 88.

- ^ http://www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/stories_events_enforce.html, retrieved August 11, 2005.

- ^ Wade, 1987, p. 102.

- ^ Wade, 1987, p. 109, writes that by ca. 1871-4, "For many, the lapse of the enforcement acts was justified since their reason for being --- the Ku-Klux Klan --- had been effectively smashed as a result of the dramatic showdown in South Carolina." Klan "costumes or regalia" had disappeared by the early 1870's (Wade, p. 109). That the Klan was entirely nonexistent for a period of decades is shown by the fact that in 1915, Simmons's refounding of the Klan was attended by only two aging "former Reconstruction Klansmen" (Wade, p. 144).A PBS web page (retrieved August 12, 2005) states that "By 1872, the Klan as an organization was broken."

- ^ Wade, 1987, pp. 109-110.

- ^ http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/jbalkin/opeds/historylesson1.pdf (PDF), retrieved August 12, 2005.

- ^ http://faculty.smu.edu/dsimon/Change-CivRts2.html, retrieved August 15, 2005.

- ^ http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USAliuzzo.htm, retrieved August 15, 2005.

- ^ New York Times, August 12, 2005, p. A14.

- ^ Dray, 2002.

- ^ http://www.geocities.com/emruf5/birthofanation.html, retrieved July 7, 2005.

- ^ Dray, 2002, p. 198. The comment was relayed to the press by Griffith and widely reported, and in subsequent correspondence, Wilson discussed Griffith's filmmaking in a highly positive tone, without challenging the veracity of the statement.

- ^ Wade, 1987, p. 137.

- ^ The Ku Klux Klan and Related American Racialist and Antisemitic Organizations: A History and Analysis by Chester L Quarles, Page 219. The second Klan's constitution and preamble, reprinted in Quarles book, states that the second Klan was indebted to the original Klan's Prescripts.

- ^ The quote is from the 1868 Revised Precept, from Horn, 1939.

- ^ Moore, Leonard J. Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921-1928 (Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina Press, 1991)

- ^ Feldman ,Glenn. Politics, Society, and the Klan in Alabama, 1915-1949. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, AL, 1999.

- ^ Rogers, William; Ward, Robert; Atkins, Leah; and Flynt, Wayne. Alabama: The History of a Deep South State. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, AL, 1994. Pages 437 and 442.

- ^ Rogers et al. Pages 432-433.

- ^ Rogers et al. Page 433.

- ^ * Moore, Leonard J. Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921-1928 Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina Press, 1991, page 186.

- ^ http://www.aaregistry.com/african_american_history/2207/The_Ku_Klux_Klan_a_brief__biography, http://www.africanamericans.com/KuKluxKlan.htm, http://www.adl.org/hate-patrol/kkk.asp, http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-2730, all retrieved August 26, 2005.

- ^ Richard von Busack, Superman Versus the KKK on the MetroActive site, accessed April 11, 2006

- ^ The Klan Unmasked by Stetson Kennedy, University Press of Florida, 1990.

- ^ Ingalls, 1979; http://www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/ref/nchistory/jan2005/jan05.html, retrieved June 26, 2005.

- ^ Thompson, 1982.

- ^ [1], retrieved June 26, 2005.

- ^ http://www.adl.org/backgrounders/american_knights_kkk.asp, retrieved June 26, 2005.

- ^ http://stop-the-hate.org/klanbody.html, retrieved June 26, 2005.

- ^ Southern Poverty Law Center. Active U.S. Hate Groups in 2004. Intelligence Report. Retrieved April 5, 2005 from http://www.splcenter.org/intel/map/hate.jsp.

- ^ http://www.adl.org/backgrounders/american_knights_kkk.asp, retrieved June 26, 2005.

- ^ http://www.adl.org/hate-patrol/kkk.asp, retrieved August 26, 2005.

- ^ Klan raises anti-immigrant clamor The Montgomery Advertiser, June 5, 2006, accessed June 5, 2006.

- ^ Axelrod, 1997, p. 160

References

- Axelrod, Alan. The International Encyclopedia of Secret Societies & Fraternal Orders, New York: Facts On File, 1997.

- Chalmers, David M., Hooded Americans: The History of the Ku Klux Klan. Historian John Hope Franklin said, "Hooded Americanism is the only work that treats Ku Kluxism for the entire period of its existence. ... It is the authoritative work on the period. Hooded Americanism is exhaustive in its rich detail and its use of primary materials to paint the picture of a century of terror. It is comprehensive, since it treats the entire period, and enjoys the perspective that the long view provides. It is timely, since it emphasizes the undeniable persistence of terrorism in American life."

- Dray, Philip. At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America, New York: Random House, 2002.

- Feldman, Glenn. Politics, Society, and the Klan in Alabama, 1915-1949. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, AL, 1999.

- Foner, Eric, * Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (1988) 1st ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1988. (Winner of the Bancroft Prize, the Francis Parkman Prize of the Society of American Historians, and the Los Angeles Times Book Award).

- Hamby, Alonzo L. Man of the People: A Life of Harry S. Truman, New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Horn, Stanley F. Invisible Empire: The Story of the Ku Klux Klan, 1866-1871, Patterson Smith Publishing Corporation: Montclair, NJ, 1939. Horn was a trade journalist in the forestry industry.

- Ingalls, Robert P. Hoods: The Story of the Ku Klux Klan, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1979.

- KKK Hearings, 46th Congress, 2d Session, Senate Report 693

- Levitt, Stephen D. and Stephen J. Dubner. Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything. New York: William Morrow (2005).

- McCullough, David. Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992.

- Moore, Leonard J. Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921-1928 Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina Press, 1991.

- Newton, Michael, The Invisible Empire: The Ku Klux Klan in Florida (University Press of Florida: 2001) ISBN: 0813021200. The author, a journalist, argues that "The Ku Klux Klan was at least as violent in Florida as anywhere else in the nation, and the sheriffs, juries, judges, politicians, press, and citizens, for the most part, as culpable in its murderous history."

- Newton, Michael, and Judy Ann Newton. The Ku Klux Klan: An Encyclopedia. New York & London: Garland Publishing, 1991.

- Parsons, Elaine Frantz, "Midnight Rangers: Costume and Performance in the Reconstruction-Era Ku Klux Klan." The Journal of American History 92.3 (2005): 811-36.

- Rhodes, James Ford. History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896. Volume: 7. (1920) Winner of the Putitzer Prize.

- Rogers, William; Ward, Robert; Atkins, Leah; and Flynt, Wayne. Alabama: The History of a Deep South State. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, AL, 1994.

- Steinberg. Man From Missouri. New York: Van Rees Press, 1962.

- Taylor, Joe G., Louisiana Reconstructed, 1863-1877 (Baton Rouge, 1974)

- Thompson, Jerry. My Life in the Klan, Rutledge Hill Press, Inc., 513 Third Avenue South, Nashville, Tennessee 37210. Originally published in 1982 by G.P. Putnam's Sons, ISBN 0399126953.

- Trelease, Allen W. White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction, (Louisiana State University Press: 1995). First published in 1971 and based on massive research in primary sources, this is the most comprehensive treatment of the Klan and its relationship to post-Civil War Reconstruction. Includes narrative research on other night-riding groups. Details close link between Klan and late 19th century and early 20th century Democratic Party.

- Truman, Margaret. Harry S. Truman. New York: William Morrow and Co. (1973).

- Tuttle, William, M. Jr. Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919 University of Illinois Press, 1996

- Wade, Wyn Craig. The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America. New York: Simon and Schuster (1987). An unsympathetic account of the Klan.

Further reading

- Kathleen M. Blee, Women of the Klan, University of California Press, 1992, ISBN 0520078764

External links

- The History of the Original Ku Klux Klan - by an anonymous author sympathetic to the original Klan

- The Southern Poverty Law Center Report

- The ADL on the KKK

- Spartacus Education about the KKK

- MIPT Terrorist Knowledge Base for the KKK

- In 1999, South Carolina town defines the KKK as terrorist

- A long interview with Stanley F. Horn, author of Invisible Empire: The Story of the Ku Klux Klan, 1866-1871.

- Full text of the Klan Act of 1871 (simplified version)

- Ku Klux Klan in the Reconstruction Era (New Georgia Encyclopedia)

- Ku Klux Klan in the Twentieth Century (New Georgia Encyclopedia)