Oil reserves

Oil reserves are the estimated quantities of crude oil that are claimed to be recoverable under existing economic and operating conditions.[1] Many oil producing nations do not reveal their reservoir engineering field data, and instead provide unsubstantiated claims for their oil reserves.

In most cases, oil refers to conventional oil and excludes oil from coal and oil shale. Depending on the source, bitumen and extra-heavy oil (tar sands) may also be excluded.[2] The exact definition varies from country to country and national statistics are not always comparable. The numbers disclosed by national governments are also often manipulated for political reasons. [3]

The total amount of oil in an oil reservoir is known as oil in place. However, because of reservoir characteristics and limitations in petroleum production technology, only a fraction of this oil can be brought to the surface, and it is only this producible fraction that is considered to be reserves. The ratio of reserves to oil in place for a given field is often referred to as the recovery factor. The recovery factor of a field may change over time based on operating history and in response to changes in technology and economics. The recovery factor may also rise over time if additional investment is made in enhanced oil recovery techniques such as gas injection or water-flooding.[4]

Because the geology of the subsurface cannot be examined directly, indirect techniques must be used to estimate the size and recoverability of the resource. While new technologies have increased the accuracy of these techniques, significant uncertainties still remain. In general, most early estimates of the reserves of an oil field are conservative and tend to grow with time. This phenomenon is called reserves growth.[5]

Types of oil reserves

Reserves are those quantities of petroleum anticipated to be commercially recoverable by application of development projects to known accumulations under defined conditions. Reserves must satisfy four criteria: They must be:

- discovered through one or more exploratory wells

- recoverable using existing technology

- commercially viable

- remaining in the ground

All reserve estimates involve uncertainty, depending on the amount of reliable geologic and engineering data available and the interpretation of those data. The relative degree of uncertainty can be expressed by dividing reserves into two principle classifications - proved and unproved. Unproved reserves can further be divided into two subcategories - probable and possible to indicate the relative degree of uncertainty about their existence. The most commonly accepted definitions of these are based on those approved by the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE) and the World Petroleum Council (WPC) in 1997.[6]

Proved reserves

Proved reserves are claimed with reasonable certainty (80% to 90% confidence) to be recoverable in future years by specified techniques. To meet this definition, the development scenario must have been defined and use known technology, and the scenario must be commercial under current economic conditions (prices and costs prevailing at the time of the evaluation).[7] Industry specialists refer to this as P90 (i.e. having a 90% certainty of being produced). Proved reserves are also known in the industry as 1P.[8]

Proved reserves are further subdivided into Proved Developed (PD) and Proved Undeveloped (PUD). PD reserves are reserves that can be produced with existing wells and perforations, or from additional reservoirs where minimal additional investment (operating expense) is required. PUD reserves require additional capital investment (drilling new wells, installing gas compression, etc.) to bring the oil and gas to the surface.

Proved reserves are the only type the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission allows oil companies to report to investors. Companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges must substantiate their claims, but many governments and national oil companies do not disclose verifying data to support their claims.

Unproved reserves

Probable reserves are based on median estimates of the accumulation that are more likely to be recovered than not (50% confidence). This can result from either better reservoir behaviour than expected under the proved category or additional investments to be decided over the medium to long term (three to ten years) using conventional techniques.[7] Industry specialists refer to this as P50 (i.e. having a 50% certainty of being produced). Proved plus probable reserves are known in the industry as 2P.[8]

Possible reserves ideally have a chance of being developed under favourable circumstances. [7] Industry specialists refer to this as P10 (i.e. having a 10% certainty of being produced). Proved plus probable plus possible reserves are known in the industry as 3P.[8]

Unproved reserves are used internally by oil companies and government agencies for future planning purposes.

Resources

A more sophisticated system of evaluating petroleum accumulations was adopted in 2007 by the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE), World Petroleum Council (WPC), American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG), and Society of Petroleum Evaluation Engineers (SPEE). It incorporates the 1997 definitions for reserves, but adds categories for contingent resources and prospective resources. [9]

Contingent resources are those quantities of petroleum estimated, as of a given date, to be potentially recoverable from known accumulations, but the applied project(s) are not yet considered mature enough for commercial development due to one or more contingencies. Contingent resources may include, for example, projects for which there are currently no viable markets, or where commercial recovery is dependent on technology under development, or where evaluation of the accumulation is insufficient to clearly assess commerciality.

Prospective resources are those quantities of petroleum estimated, as of a given date, to be potentially recoverable from undiscovered accumulations by application of future development projects. Prospective resources have both an associated chance of discovery and a chance of development.

The United States Geological Survey uses the terms technically and economically recoverable resources when making its petroleum resource assessments. Technically recoverable resources represent that proportion of assessed in-place petroleum that may be recoverable using current recovery technology, without regard to cost. Economically recoverable resources are technically recoverable petroleum for which the costs of discovery, development, production, and transport, including a return to capital, can be recovered at a given market price.

Unconventional resources exist in petroleum accumulations that are pervasive throughout a large area. Examples include extra heavy oil, natural bitumen, and oil shale deposits. Unlike Conventional resources, in which the petroleum is recovered through wellbores and typically requires minimal processing prior to sale, unconventional resources require specialized extraction technology to produce. For example, steam and/or solvents are used to mobilize bitumen for in-situ recovery. Moreover, the extracted petroleum may require significant processing prior to sale (e.g. bitumen upgraders).[9] The total amount of unconventional oil resources in the world considerably exceeds the amount of conventional oil reserves, but are much more difficult and expensive to develop.

Calculating oil reserves

The amount of oil in a subsurface reservoir is called oil in place (OIP). Only a fraction of this oil can be recovered from a reservoir, and this is the portion that is considered to be a reserve. The portion that is not recoverable is not included unless and until methods are implemented to produce it.

There are a number of different methods of calculating oil reserves. These methods can be grouped into three general categories: volumetric, material balance, and production performance. Each method has it's advantages and drawbacks. [11] [12]

Volumetric method

Volumetric methods attempt to determine the amount of oil-in-place and reserves by using the size of the reservoir as well as the physical properties of rocks and fluids. The method is most useful early in the life of the reservoir, before significant production has occured.

The volumetric or engineering formula for an oil well or field is:

- STV = k × V × P × So × R / FVF

Where:

- STV = stock tank volume

- k = a constant, depending on units of measurement

- V = volume of reservoir, from geological and geophysical studies

- P = porosity of the reservoir, from well logs or core samples

- So = oil saturation, from well logs or cores

- R = recovery factor, estimated from reservoir drive, permeability and oil viscosity

- FVF = formation volume factor, estimated from production data or laboratory analysis of oil

When oil is produced, the high reservoir temperature and pressure decreases to surface conditions and gas bubbles out of the oil. As the gas bubbles out of the oil, the volume of the oil decreases. Stabilized oil under surface conditions (either 60 F and 14.7 psi or 15 C and 101.325 kPa) is called stock tank oil. Oil reserves are calculated in terms of stock tank oil volumes rather than reservoir oil volumes. The ratio of stock tank volume to oil volume under reservoir conditions is called the formation volume factor (FVF). It usually varies from 1.0 to 1.7. A formation volume factor of 1.4 is characteristic of high-shrinkage oil and 1.2 of low-shrinkage oil.

The recovery factor is the percentage of the oil in place that can be produced from the reservoir. The recovery factor depends on the viscosity of the oil (resistance of the oil to flow), the permeability of the reservoir (ability of a crude oil to flow through the pores in the reservoir rock to the well), and the reservoir drive (what creates and maintain pressure in the field besides pumps). During the primary recovery stage, reservoir drive is the result of the combination of a number of natural mechanisms:

- Natural water drive resulting from the rise of the water layer below the oil column in the reservoir, displacing oil upward into the well. The root cause of this is the inflow of water into the reservoir from adjacent aquifers.

- Gas-cap drive resulting from the expansion of the natural gas at the top of the reservoir, above the oil column, which displaces the oil downward in the direction of the producing wells.

- Dissolved gas drive that results from the dissolution and expansion of gas initially dissolved in the crude oil.

- Gravity drainage resulting from the movement of oil within the reservoir from the upper to the lower parts where the wells are located, driven by gravitational forces.

Recovery factor during the primary stage is typically 5-15%. After natural reservoir drive diminishes, secondary recovery methods are applied. They rely on the supply of external energy into the reservoir in the form of injecting fluids to increase reservoir pressure, hence replacing or increasing the natural reservoir drive with an artificial drive. Typically this is done by injecting water (water-flooding) in the reservoir using a number of injection wells. Typical recovery factor from water-flood operations is about 30%, depending on the properties of oil and the characteristics of the reservoir rock. On average, the recovery factor after primary and secondary oil recovery operations is between 30 and 50%. After this stage, tertiary or enhanced oil recovery techniques may be applied. These refer to to a number of operations that are typically done towards the end of life of an oilfield, to maintain oil production and produce an additional 5-15% original OIP. Examples include injection CO2 to improve oil flow.[13] [14]

Materials balance method

The materials balance method for an oil field uses an equation that relates the volume of oil, water and gas that has been produced from a reservoir, and the change in reservoir pressure, to calculate the remaining oil. It assumes that as fluids from the reservoir are produced, there will be a change in the reservoir pressure that depends on the remaining volume of oil and gas. The method requires extensive pressure-volume-temperature analysis and an accurate pressure history of the field. It requires some production to occur (typically 5% to 10% of ultimate recovery), unless reliable pressure history can be used from a field with similar rock and fluid characteristics.

Production decline curve method

The decline curve method uses production data to fit a decline curve and estimate future oil production. The three most common forms of decline curves are exponential, hyperbolic, and harmonic. It is assumed that the production will decline on a reasonably smooth curve, and so allowances must be made for wells shut in and production restrictions. The curve can be expressed mathematically or plotted on a graph to estimate future production. If the oil well produces with a gas drive, it can produce a straight line on a logarithmic production scale. It has the advantage of (implicitly) including all reservoir characteristics. It requires a sufficient history to establish a statistically significant trend, ideally when production is not curtailed by regulatory or other artificial conditions.

Estimated reserves in order

Estimating the amount of oil in any particular oil field involves a degree of uncertainty until the last barrel of oil is produced and the last oil well is abandoned. The following estimates are the best that could be obtained using publicly available data, and the confidence in them varies greatly from country to country. Estimates in developed countries are generally much more accurate than those for undeveloped countries. For instance, reserves estimates in the United States are considered highly conservative, while those Russia are more speculative, and those in Iraq are highly uncertain due to the lack of exploration data. In many countries (particularly OPEC producers) the estimates may involve a great deal of political influence. The raw data underlying reserves estimates is considered a state secret in some countries, so independent assessments of their reserves cannot be made.

| Country | Reserves 1 | Production 2 | Reserve life 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 109 bbl | 109 m3 | 106 bbl/d | 103 m3/d | years | |

| Saudi Arabia | 260 | 41 | 8.8 | 1,400 | 81 |

| Canada | 179 | 28.5 | 2.7 | 430 | 182 |

| Iran | 136 | 21.6 | 3.9 | 620 | 96 |

| Iraq | 115 | 18.3 | 3.7 | 590 | 85 |

| Kuwait | 99 | 15.7 | 2.5 | 400 | 108 |

| United Arab Emirates | 97 | 15.4 | 2.5 | 400 | 106 |

| Venezuela | 80 | 13 | 2.4 | 380 | 91 |

| Russia | 60 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 1,510 | 17 |

| Libya | 41.5 | 6.60 | 1.8 | 290 | 63 |

| Nigeria | 36.2 | 5.76 | 2.3 | 370 | 43 |

| United States | 21 | 3.3 | 4.9 | 780 | 11 |

| Mexico | 12 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 510 | 10 |

| Total of top twelve reserves | 1,137 | 180.8 | 48.2 | 7,660 | 65 |

Notes:

| |||||

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia has the largest proven oil reserves in the world, estimated to be 267 billion barrels (42×109 m3) including 2.5 billion barrels in the Saudi-Kuwaiti neutral zone. This is around one-fifth of the world's total conventional oil reserves. Although Saudi Arabia has around 100 major oil and gas fields, over half of its oil reserves are contained in only eight giant oil fields, including the Ghawar Field, the biggest oil field in the world with an estimated 70 billion barrels (11×109 m3) of remaining reserves. Saudi Arabia maintains the world’s largest crude oil production capacity, estimated to be around 11 million barrels per day (1.7×106 m3/d) at mid-year 2008 and has announced plans to increase this capacity to 12.5 million barrels per day (2.0×106 m3/d) by 2009[17]

Saudi Arabia produced 10.6 million barrels per day in 2006, and 10.3 million in 1980.[18] At the beginning of 2008, the kingdom was producing around 9.2 million barrels per day (1.46×106 m3/d) of oil.[19] After US President Bush asked the Saudis to raise production on a visit to Saudi Arabia in January 2008, and they declined, Bush questioned whether they had the ability to raise production any more.[20] In the summer of 2008, Saudi Arabia announced an increase in planned production of 500,000 barrels per day.[21] However there are experts who believe Saudi oil production has already peaked or will do so soon.[18]

Despite its large number of oil fields, 90 percent of Saudi Arabia's oil production comes from only five fields, and up to 60 percent of its production comes from the Ghawar field.[22] Since 1982 the Saudis have withheld their well data and any detailed data on their reserves, giving outside experts no way to verify Saudi claims regarding the overall size of their reserves and output. This has causes some to question the current state of their oil fields. In a study discussed in Matthew Simmons book Twilight in the Desert, 200 technical papers on Saudi reserves by the Society of Petroleum Engineers were analyzed to reach the conclustion that Saudi Arabia's oil production faces near term decline, and that it will not be able to consistently produce more than current levels.[22] Simmons also argues that the Saudis may have irretrievably damaged their large oil fields by over-pumping salt water into the fields in an effort to maintain the fields' pressure and boost short term oil extraction amounts.

Canada

Canada's proven oil reserves were estimated at 179 billion barrels (28×109 m3) in 2007. This figure includes oil sands reserves which are estimated by government regulators to be economically producible at current prices using current technology.[23] According to this figure, Canada's reserves are second only to Saudi Arabia. Over 95% of these reserves are in the oil sands deposits in the province of Alberta. [24] Alberta contains nearly all of Canada's oil sands and much of its conventional oil reserves. The balance is concentrated in several other provinces and territories. Saskatchewan and offshore areas of Newfoundland in particular have substantial oil production and reserves.[25] Alberta has 39% of Canada's remaining conventional oil reserves, Saskatchewan 27% and offshore Newfoundland 28%, but if oil sands are included, Albert's share is over 98%.[26]

Canada has a highly sophisticated energy industry and is both an importer and exporter of oil and refined products. In 2006, in addition to producing 1.2 billion barrels (190×106 m3), Canada imported 440 million barrels (70×106 m3), consumed 800 million barrels (130×106 m3) itself, and exported 840 million barrels (134×106 m3) to the U.S.[24] The excess of exports over imports was 400 million barrels (64×106 m3). Over 99% of Canadian oil exports are sent to the United States, and Canada is the United States' largest supplier of oil.[27]

The decision of accounting 174 billion barrels (28×109 m3) of the Alberta oil sands deposits as proven reserves was made by the Alberta Energy and Utilities Board (AEUB), now known as the Energy Resources Conservation Board (ERCB).[28] Although now widely accepted, this addition was controversial at the time because oil sands contain an extremely heavy form of crude oil known as bitumen which will not flow toward a well under reservoir conditions. Instead, it must be mined, heated, or diluted with solvents to allow it to be produced, and must be upgraded to lighter oil to be usable by refineries.[28]. Historically known as bituminous sands or sometimes as "tar sands", the deposits were exposed as major rivers cut through the oil-bearing formations to reveal the bitumen in the river banks. In recent years technological breakthroughs have overcome the economical and technical difficulties of producing the oil sands, and by 2007 64% of Alberta's petroleum production of 1.86 million barrels per day (296,000 m3/d) was from oil sands rather than conventional oil fields. The ERCB estimates that by 2017 oil sands production will make up 88% of Alberta's predicted oil production of 3.4 million barrels per day (540,000 m3/d).[28]

Analysts estimate that a price of $30 to $40 per barrel is required to make new oil sands production profitable.[24] In recent years prices have greatly exceeded those levels and the Alberta government expects $116 billion worth of new oil sands projects to be undertaken between 2008 and 2017.[28] However the biggest constraint on oil sands development is a serious labor and housing shortage in Alberta as a whole and the oil sands center of Fort McMurray in particular. According to Statistics Canada, by September, 2006 unemployment rates in Alberta had fallen to record low levels[29] and per-capita incomes had risen to double the Canadian average. Another hurdle has been Canada's capacity to rapidly increase its export pipelines. The National Energy Board indicated that exporters faced pipeline apportionment in 2007.[30] However, surging crude oil prices sparked a jump in applications for oil pipelines in 2007, and new pipelines were planned to carry Canadian oil as far south as U.S. refineries on the Gulf of Mexico.[31]

Canada is the only major oil producer in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to have an increase in oil production in recent years. Production in the other major OECD producers (the United States, United Kingdom, Norway and Mexico) have been declining, as has conventional oil production in Canada. But total crude oil production in Canada was projected to increase by an average of 8.6 percent per year from 2008 to 2011 as a result of new non-conventional oil projects.[32]

Iran

Iran claims to have the world's third largest reserves of oil at approximately 136 billion barrels (21.6×109 m3) as of 2007, although it ranks second if Canadian reserves of non-conventional oil are excluded. This is roughly 10% of the world's total proven petroleum reserves. Iran is the world's fourth largest oil producer and is OPEC's second-largest producer after Saudi Arabia. As of 2006 it was producing an estimated 3.8 million barrels per day (600×103 m3/d) of crude oil, equal to 5% of global production.[33] At 2006 rates of production, Iran's oil reserves would last 98 years if no new oil was found.

Iranian production peaked at 6 Mbbl/d (950×103 m3/d) in 1974, but it has been unable to produce at that rate since the 1979 Iranian Revolution due to a combination of political unrest, war with Iraq, limited investment, US sanctions, and a high rate of natural decline. Iran's mature oil fields are in need of enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques such as gas injection to maintain production, which is declining at an annual rate of approximately 8% onshore and 10% offshore. With its current technology it is only able to recover about 25% of the oil in place, 10% less than the world average. Iran consumed 1.6 Mbbl/d (250×103 m3/d) of its own oil as of 2006. Domestic consumption is increasing due to a growing population and large government subsidies on gasoline, which reduces the amount of oil available for export and contributes to a large government budget deficit. Due to a lack of refinery capacity, Iran is the second biggest gasoline importer in the world after the United States.[33] High oil prices in recent years have enabled Iran to amass nearly $60 billion in foreign exchange reserves, but have not helped solve economic problems such as high unemployment and inflation.[34]

Iraq

Iraq claims to have the world's fourth largest reserves of oil at approximately 115 billion barrels (18.3×109 m3), although it would rank third if Canadian reserves of non-conventional oil were excluded.

As a result of war and civil unrest, these statistics have not been revised since 2001 and are largely based on 2-D seismic data from three decades ago. International geologists and consultants have estimated that unexplored territory may contain an estimated additional 45 to 100 billion barrels (bbls) of recoverable oil.[35] However, in the absence of exploration data these estimates are highly speculative and do not meet the industry definitions of proven, probable, or possible oil reserves (see above).

A measure of the uncertainty about Iraq's oil reserves is indicated by the fact that the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) estimated that Iraq had 112 billion barrels (17.8×109 m3), whereas the United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimated it was closer to 78 Gbbl (12.4×109 m3) and Iraq's prewar deputy oil minister claimed it might have 300 Gbbl (48×109 m3). The source of the uncertainty is that due to decades of war and unrest, Iraq's western desert (which would contain almost all of the undiscovered oil), remains almost completely unexplored.[36]

After more than a decade of sanctions and two Gulf Wars, Iraq’s oil infrastructure needs modernization and investment. Despite a large reconstruction effort, the Iraqi oil industry has not been able to meet hydrocarbon production and export targets. The World Bank estimates that an additional $1 billion per year would need to be invested just to maintain current production. Long-term Iraq reconstruction costs could reach $100-billion or higher, of which more than a third will go to the oil, gas and electricity sectors. Another challenge to Iraq's development of the oil sector is that resources are not evenly divided across sectarian lines. Most known resources are in the Shiite areas of the south and the Kurdish north, with few resources in control of the Sunni population in the center.

In 2006, Iraq's oil production averaged 2.0 million barrels per day (320×103 m3/d), down from around 2.6 Mbbl/d (410×103 m3/d) of production prior to the coalition invasion in 2003.[35] At this rate of production, Iraq will have 158 years of reserves if no new oil is discovered.

Kuwait

Kuwait is OPEC's third largest oil producer and claims to hold approximately 104 billion barrels (16.5×109 m3), 8% of the world's world oil reserves. This includes half of the 5 billion barrels (790×106 m3) in the Neutral Zone which Kuwait shares with Saudi Arabia. Most of Kuwait's oil reserves are located in the 70 billion barrels (11×109 m3) Burgan field, the second largest conventional oil field in the world, which has been producing oil since 1938. Since most of Kuwait's major oil fields are over 60 years old, maintaining production rates is becoming a problem. The size of Kuwait's reserves came into question in 2006 when a leaked memo from the Kuwait Oil Company (KOC) reported by Petroleum Intelligence Weekly that national reserves of were some 48 billion barrels. The estimate came from adding up the following reserves: Burgan field : 20 bnb, Northern fields : 17 bnb, Western fields : 8.5 bnb, Neutral Zone : 2.5 bnb [for 50% share]. Kuwait produces about 2.6 million barrels per day (410×103 m3/d) which gives it about 100 years of reserves at current production rates.[37]

United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) claims to have oil reserves of about 98 billion barrels (15.6×109 m3), almost as big as Kuwait's claimed reserves. Of the emirates, Abu Dhabi has most of the oil with 92 billion barrels (14.6×109 m3) while Dubai has 4 billion barrels (640×106 m3) and Sharjah has 1.5 billion barrels (240×106 m3). Most of the oil is in the the Zakum field which is the third largest in the Middle East with an estimated 66 billion barrels (10.5×109 m3). The UAE produces about 2.9 million barrels per day (460×103 m3/d) of total oil liquids, but has stated its intention to increase this to 5 million barrels per day (790×103 m3/d) by 2014. At current rates of production the UAE has about 93 years of remaining oil reserves.[38]

Venezuela

Venezuela had 80 billion barrels (13×109 m3) of conventional oil reserves as of 2007, the largest oil reserves of any country in South America. In 2006, it had net oil exports of 2.2 million barrels per day (350×103 m3/d), the sixth-largest in the world and the largest in the Western Hemisphere. In recent years, crude oil production has been falling, mostly due to depletion of existing oil fields and, since many of its oil fields suffer production decline rates of at least 25 percent per year, industry analysts estimate that Venezuela must spend some $3 billion each year just to maintain production levels. As a result of the lack of transparency in the country's accounting, Venezuela's true level of oil production is difficult to determine, but most industry analysts estimate that it produced around 2.8 million barrels per day (450×103 m3/d) of oil in 2006[39] This would give it 88 years of remaining production at current rates.

In October 2007 the Venezuelan government said its proven oil reserves had risen to 100 billion barrels (16×109 m3). The energy and oil ministry said it had certified an additional 12.4 billion barrels (2.0×109 m3) of proven reserves in the country's Faja del Orinoco region.[40]

In addition to conventional oil, Venezuela has oil sands deposits similar in size to those of Canada (approximately equal to the world's reserves of conventional oil). Venezuela's Orinoco tar sands are less viscous than Canada's Athabasca oil sands – meaning they can be produced by more conventional means, but they are buried deeper – meaning they cannot be extracted by surface mining. Estimates of the recoverable reserves of the Orinoco Belt range from 100 billion barrels (16×109 m3) to 270 billion barrels (43×109 m3). However, they are not generally considered proven reserves since Venezuela lacks enough technological expertise and capital to develop them on a sufficiently large scale.

Venezuela's development of its oil reserves has been affected by political unrest in recent years. In late 2002 nearly half of the workers at the state oil company PDVSA went on strike, after which the company fired 18,000 of them. In the opinion of many industry analysts this affected its ability to maintain its oil fields and has contributed to declines in oil production. The crude oil that Venezuela has is very heavy by international standards, and as a result much of it must be processed by specialized domestic and international refineries. Venezuela continues to be one of the largest suppliers of oil to the United States, sending about 1.4 million barrels per day (220×103 m3/d) to the U.S. Venezuela is also a major oil refiner and the owner of the Citgo gasoline chain.[39]

Russia

Estimates of proven reserves vary wildly. Most estimates include only Western Siberian reserves, exploited since the 1970s and supplying two-thirds of Russian oil, and not potentially huge reserves elsewhere. In 2005, the Russian Ministry of Natural Resources estimated that another 4.7 billion barrels (0.75×109 m3) of oil exist in Eastern Siberia.[41]

Following the collapse of the former Soviet Union, Russia’s petroleum output fell sharply, and has rebounded only in the last several years. Russia reached a peak of 12.5 million barrels per day (1.99×106 m3/d) in total liquids in 1988, and production had fallen to around 6 Mbbl/d (950×103 m3/d) by the mid 1990's. A turnaround in Russian oil output began in 1999, which many analysts attribute to the privatization of the industry. Higher world oil prices, the use of Western technology, and the rejuvenation of old oil fields also helped. By 2007 Russian production had recovered to 9.8 Mbbl/d (1.56×106 m3/d), but was growing at a slower rate than 2002-2004.[41] In 2008, production fell 1 percent in the first quarter and Lukoil vice president Leonid Fedun said $1 trillion would have to be spent on developing new reserves if current production levels were to be maintained. The editor in chief of the Russian Petroleum Investor claims that Russian production had reached a secondary peak in 2007.[42]

In 2007, Russia produced roughly 9.8 Mbbl/d (1.56×106 m3/d) of liquids, consumed roughly 2.8 Mbbl/d (450×103 m3/d) in liquids, and exported (in net) around 7 Mbbl/d (1.1×106 m3/d). Over 70 percent of Russian oil production was exported, while the remaining 30 percent was refined locally.[43] In early 2008 Russian officials were reported to be concerned because, after rising just 2% during 2007, oil production started to decline again in 2008. The government proposed tax cuts on oil in an attempt to stimulate production.[44]

| 109 bbl | 109 m3 | |

|---|---|---|

| Oil & Gas Journal | 60 | 9.5 |

| John Grace* | 68 | 10.8 |

| World Oil | 69 | 11.0 |

| British Petroleum | 72 | 11.4 |

| 10 largest Russian Oil Companies | 82 | 13.0 |

| E Khartukov (Russian Oil Expert) | 110 | 17 |

| United States Geological Survey | 116 | 18.4 |

| Ray Leonard (MOL) | 119 | 18.9 |

| Wood Mackenzie | 120 | 19 |

| IHS Energy | 120 | 19 |

| M. Khodorkovsky | 150 | 24 |

| Brunswick UBS (consultants) | 180 | 29 |

| DeGolyer & MacNaughton (audit) (proven SPE?) | 150–200 | 24–32 |

Libya

Libya holds the largest oil reserves in Africa and the ninth largest oil reserves in the world with 41.5 billion barrels (6.60×109 m3) as of 2007. Oil production was 1.8 million barrels per day (290×103 m3/d) as of 2006, giving Libya 63 years of reserves at current production rates if no new reserves were to be found. Libya is considered a highly attractive oil area due to its low cost of oil production (as low as $1 per barrel at some fields), and proximity to European markets. Libya would like to increase production from 1.8 Mbbl/d (290×103 m3/d) in 2006 to 3 Mbbl/d (480×103 m3/d) by 2010–13 but with existing oil fields undergoing a 7–8% decline rate, Libya's challenge is maintaining production at mature fields, while finding and developing new oil fields. Most of Libya remains unexplored as a result of past sanctions and disagreements with foreign oil companies.[46]

Nigeria

Although Libya has more reserves, Nigeria with 36.2 billion barrels (5.76×109 m3) of proven reserves as of 2007 ranks as the largest oil producer in Africa and the 11th largest in the world, averaging 2.28 million barrels per day (362×103 m3/d) as of 2006. At current rates this would be 43 years of supply if no new oil was found. Pipeline vandalism, kidnappings, and militant takeover of oil facilities have reduced production, which could be increased to 3 million barrels per day (480×103 m3/d) in the absence of such problems. The Nigerian government hopes to increase oil production capacity to 4 Mbbl/d (640×103 m3/d) by 2010. Nigeria is the world’s eighth largest exporter of crude oil and sends 42% of its exports to the United States. Nigeria is heavily dependent on the oil sector, which accounts for 95% of its export revenues.[47]

Prospective resources

Nigeria and Sao Tome have an agreement in which the Joint Development Authority was created to explore and produce oil in the waters between Sao Tome and Nigeria. Nigeria and Sao Tome share together in this area, called the Joint Development Zone ( or JDZ ), and has what many oil companies are calling one of the greatest finds in the history of oil fields. That this area could contain up to and above 14 billion barrels of oil, along with a huge quantity of natural gas in the JDZ. In 2006 Chevron drilled an exploratory well called OBO-1 and news reports came out that they had indeed discovered over a billion barrels of oil in block 1 alone. The news reports, reported on CNN, AP, and FoxNews quickly quieted down and no more news came out from Chevron.[citation needed]

United States

Proven reserves

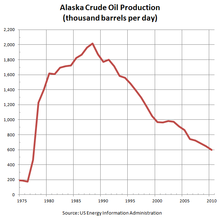

United States proven oil reserves were 21 billion barrels (3.3×109 m3) in 2006 according to the Energy Information Administration. [48] This represents a decline of 46%, or 18 billion barrels (2.9×109 m3) from 39 billion barrels (6.2×109 m3) in 1970. U.S. crude production peaked in 1970 at 9.6 million barrels per day (1.53×106 m3/d), and had declined 47% to 5.1 million barrels per day (810×103 m3/d) by 2006. [49] United States crude oil production has been declining since reaching a smaller secondary production peak in 1988 (caused by Alaskan production). Total production of crude oil from 1970 through 2006 was 102 billion barrels (16.2×109 m3), or roughly five and a half times the decline in proved reserves.[50]

Proved reserves divided by current production equaled an 11.26 years supply in 2007. Proved reserves divided by production was 11.08 years in 1970. It hit a trough of 8.49 years in 1986 as oil pumped through the alaska pipeline began to peak.[51]

Because of declining production and increasing demand, Net US imports of oil and petroleum products increased by 400% from 3.16 million barrels per day (502×103 m3/d) in 1970 to 12.04 million barrels per day (1.914×106 m3/d) in 2007. Its largest net suppliers of petroleum products in 2007 were Canada and Mexico, which supplied 2.2 and 1.3 Mbbl/d (350×103 and 210×103 m3/d), respectively.[52]

Net imports of oil and products account for nearly half of the US trade deficit. As of 2007, the US consumed 20.68m bbls of petroleum products/day and imported a net 12.04m bbls/day. The EIA reports the United States "Dependence on Net Petroleum Imports" as 58.2%.[53]

Prospective resources

Services under the U.S. Department of the Interior estimate the total volume of undiscovered, technically recoverable oil in the United States to be be roughly 134 billion barrels. Over 2.3 million wells have been drilled in the US since 1949.[56]

The Minerals Management Service (MMS) estimates the Federal Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) contains between 66.6 and 115.1 billion barrels (10.59×109 and 18.30×109 m3) of undiscovered technically recoverable crude oil, with a mean estimate of 85.9 billion barrels (13.66×109 m3). The Gulf of Mexico OCS ranks first with a mean estimate of 44.9 billion barrels (7.14×109 m3), followed by Alaska OCS with 38.8 billion barrels (6.17×109 m3). At $80/bbl crude prices, the MMS estimates that 70 billion barrels (11×109 m3) are economically recoverable. As of 2008, a total of about 574 million acres of the OCS are off-limits to leasing and development. The moratoria and presidential withdrawal cover about 85 percent of OCS acreage offshore the lower 48 states. The MMS estimates that the resources in OCS areas currently off limits to leasing and development total 17.8 billion barrels (2.83×109 m3)(mean estimate).[54]

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimates undiscovered technically recoverable crude oil onshore in United States to be 48.5 billion barrels (7.71×109 m3) [55] [57] The last comprehensive National Assessment was completed in 1995. Since 2000 the USGS has been re-assessing basins of the U.S. that are considered to be priorities for oil and gas resources. Since 2000, the USGS has re-assessed 22 priority basins, and has plans to re-assess 10 more basins. These 32 basins represent about 97% of the discovered and undiscovered oil and gas resources of the United States. The three areas considered to hold the most amount of oil are the coastal plain (1002) area of ANWR, the National Petroleum Reserve of Alaska, and the Bakken Formation.

In 1998, the USGS estimated that 1002 area of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge contains a total of between 5.7 and 16.0 billion barrels of undiscovered, technically recoverable oil, with a mean estimate of 10.4 billion barrels, of which 7.7 billion barrels falls within the Federal portion of the ANWR 1002 Area. [58] In May 2008 the EIA used this assesment to estimate the potential cumulative production of the 1002 area of ANWR to be a maximum of 4.3 billion barrels from 2018 to 2030. This estimate is a best case scenario of technically recoverable oil during the area's primary production years if legislation were passed in 2008 to allow drilling. [59]

A 2002 assessment concluded that the National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska contains between 6.7 and 15.0 billion barrels of oil, with a mean (expected) value of 10.6 billion barrels. The quantity of undiscovered oil beneath Federal lands (excluding State and Native areas) is estimated to range between 5.9 and 13.2 BBO, with a mean value of 9.3 BBO. Most oil accumulations are expected to be of moderate size, on the order of 30 to 250 million barrels each. Large accumulations like the Prudhoe Bay oil field (whose ultimate recovery is approximately 13 billion barrels), are not expected to occur. The volumes of undiscovered, technically recoverable oil estimated for NPRA are similar to the volumes estimated for ANWR. However, because of differences in accumulation sizes (the ANWR study area is estimated to contain more accumulations in larger size classes) and differences in assessment area (the NPRA study area is more than 12 times larger than the ANWR study area), economically recoverable resources are different at low oil prices. But at market prices above $40 per barrel, estimates of economically recoverable oil for NPRA are similiar to ANWR.[60]

In April 2008, the USGS released a report giving a new resource assessment of the Bakken Formation underlying portions of Montana and North Dakota. The USGS believes that with new horizontal drilling technology there is somewhere between 3.0 and 4.5 billion barrels (480×106 and 720×106 m3) of undiscovered, technically recoverable oil in this 200,000 square miles (520,000 km2) formation that was initially discovered in 1951. If accurate, this reassessment would make it the largest continuous oil formation ever discovered in the U.S.[57]

Unconventional prospective resources

Oil shale

The United States has the largest known deposits of oil shale in the world, according to the Bureau of Land Management and holds an estimated 2,175 gigabarrels of potentially recoverable oil.[61] Oil shale does not actually contain oil, but a waxy oil precursor known as kerogen. There is no significant commercial production of oil from oil shale in the United States.

Mexico

The Oil and Gas Journal (OGJ) estimated that as of 2007, Mexico had 12.4 billion barrels (1.97×109 m3) of proven oil reserves. Mexico was the sixth-largest oil producer in the world as of 2006, producing 3.71 million barrels per day (590×103 m3/d). However, at that rate its oil reserves represent only a nine year supply of oil, and Mexican oil production has started to decline rapidly. The U.S. Energy Information Administration had estimated that Mexican production would decline to 3.52 million barrels per day (560×103 m3/d) in 2007 and 3.32 million barrels per day (528×103 m3/d) in 2008.[62] Mexican oil production fell much faster than expected in 2007, and was below 3.0 million barrels per day (480×103 m3/d) by the start of 2008. In mid-2008, Pemex said that it would try to keep oil production above 2.8 million barrels per day (450×103 m3/d) for the rest of the year.[63] Mexican authorities expected the decline to continue in future, and were pessimistic that it could be raised back to previous levels even with foreign investment.[64]

In Mexico, oil production is a state monopoly. The constitution of Mexico gives the state oil company, PEMEX, exclusive rights over oil production, and the Mexican government treats Pemex as a major source of revenue. As a result, Pemex has insufficient capital to develop new and more expensive resources on its own, and cannot take on foreign partners to supply money and technology it lacks.[65] To address some of these problems, in September 2007, Mexico’s Congress approved reforms including a reduction in the taxes levied on Pemex.[62]

Most of Mexico's production decline involves one enormous oil field in the Gulf of Mexico. From 1979 to 2007, Mexico produced most of its oil from the supergiant Cantarell Field, which used to be the second-biggest oil field in the world by production. Because of falling production, in 1997 Pemex started a massive nitrogen injection project to maintain oil flow, which now consumes half the nitrogen produced in the world. As a result of nitrogen injection, production at Cantarell rose from 1.1 million barrels per day (170×103 m3/d) in 1996 to a peak of 2.1 million barrels per day (330×103 m3/d) in 2004. However, during 2006 Cantarell's output fell 25% from 2.0 million barrels per day (320×103 m3/d) in January to 1.5 million barrels per day (240×103 m3/d) in December, with the decline continuing through 2007.[62] In mid-2008, Pemex announced that it would try to end the year with Cantarell producing at least 1.0 million barrels per day (160×103 m3/d).[63]

As for its other fields, 40% of Mexico's remaining reserves are in the Chicontepec Field, which was found in 1926. The field has remained undeveloped because the oil is trapped in impermeable rock, requiring advanced technology and very large numbers of oil wells to extract it. The remainder of Mexico's fields are smaller, more expensive to develop, and contain heavy oil and trades at a significant discount to light and medium oil, which is easier to refine.

In 2002 PEMEX began developing an oil field called "Proyecto Ku-Maloob-Zaap", located 105 kilometers from Ciudad del Carmen. It is estimated that by 2011 the field will produce nearly 800 thousand barrels per day (130×103 m3/d).[citation needed] However, this level of production will be achieved by using a nitrogen injection scheme similar to that of Cantarell.

In June, 2007 former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan warned that declining oil production in Mexico could cause a major fiscal crisis there, and that Mexico needed to increase investment in its energy sector to prevent it.[66]

Arctic prospective resources

A 2008 United States Geological Survey estimates that areas north of the Arctic Circle have 90 billion barrels of undiscovered, technically recoverable oil (and 44 billion barrels of natural gas liquids ) in 25 geologically defined areas thought to have potential for petroleum. This represents 13 percent of the undiscovered oil in the world. Of the estimated totals, more than half of the undiscovered oil resources are estimated to occur in just three geologic provinces - Arctic Alaska, the Amerasia Basin, and the East Greenland Rift Basins. More than 70 percent of the mean undiscovered oil resources is estimated to occur in five provinces: Arctic Alaska, Amerasia Basin, East Greenland Rift Basins, East Barents Basins, and West Greenland–East Canada. It is further estimated that approximately 84 percent of the undiscovered oil and gas occurs offshore. The USGS did not consider economic factors such as the effects of permanent sea ice or oceanic water depth in its assessment of undiscovered oil and gas resources. This assessment is lower than a 2000 survey which estimated Arctic reserves to be 14 percent of total world reserves. The 2000 survey included lands south of the arctic circle. [67] [68] [69]

Canada

Extensive drilling was done in the Canadian Arctic during the 1970s and 1980s by such companies as Panarctic Oils Ltd., Petro Canada and Dome Petroleum. They discovered significant oil reserves, but not enough to justify the cost of an oil pipeline to southern Canada or the United States. Billions of dollars were spent to drill 176 wells in the Canadian Arctic, and discovered approximately 1.9 billion barrels (300×106 m3) of oil and 19.8 trillion cubic feet (560×109 m3) of natural gas. These discoveries were insufficient to justify development, and all the wells which were drilled have since been plugged and abandoned. Drilling in the Arctic turned out to be extremely expensive and dangerous, but drilling efforts were terminated not because the exploring companies ran out of money, but because they ran out of prospects. The geology of the Canadian Arctic turned out to be far more complex than oil-producing regions like the Gulf of Mexico. It was discovered to be gas prone rather than oil prone (i.e. most of the oil had been transformed into natural gas by geological processes), and most of the reservoirs had been fractured by tectonic activity, allowing most of the petroleum which might at one time have been present to leak out.[70]

Currently, the Arctic ice pack makes the shipping season too short to justify shipping oil out by tanker, but it is possible future global warming could melt the Arctic ice pack and make tanker shipment feasible.[citation needed] In 2007 the Canadian Navy announced its intention to build up to eight new polar class 5 Arctic offshore patrol ships to assert sovereignty over its Arctic waters in anticipation of such a possibility.

Greenland

Greenland is believed by some geologists to have some of the world’s largest remaining oil reserves[71]. Prospecting is taking place under the auspices of NUNAOIL, a partnership between the Greenland Home Rule Government and the Danish state. U.S. Geological Survey found in 2001 that the waters off north-eastern Greenland could contain up to 110 billion barrels (17×109 m3) of oil which compares to half of the known reserves in Saudi Arabia.[72] This amount of oil, distributed on the just 57,000 inhabitants, would mean tens of millions of dollars per Greenlander. Many Greenlanders hope that oil finds can trigger independence or more advanced self-government. In March 2008, the Greenlandic Self-Government Commission concluded its work after two years of negotiations between the Home Rule Government and Danish bodies, the future distribution of oil revenues between the Home Rule Government and the Kingdom of Denmark being a major issue.

Middle Eastern reserves

There are varying estimates of how much oil is left in Middle Eastern reserves. Several oil companies and the U.S. Department of Energy state that the Middle East has two-thirds of all the world's oil reserves. Other oil experts, however, argue that the Middle East has two-thirds of only all proven oil reserves, and that the percentage of all oil reserves it has could be much lower than two-thirds.[citation needed] The U.S. Geological Survey says that the Middle East has only between half and a third of the recoverable oil reserves in the world.

Suspicious official estimates of oil reserves from OPEC countries

The OPEC countries decided in 1985 to link their production quotas to their reserves. What then seemed wise provoked important increases of the estimates in order to increase their production rights. This also permits the ability to obtain bigger loans at lower interest rates. This is a suspected reason for the reserves rise of Iraq in 1983, then at war with Iran.

Dr. Ali Samsam Bakhtiari, a former senior expert of the National Iranian Oil Company, has stated that OPEC's oil reserves are overstated, and "As for Iran, the usually accepted official 132 billion barrels is almost one hundred billion over any realistic assay".[73] In an interview to Bloomberg in July 2006, he stated that world oil production is now at its peak and predicted that it will fall 32% by 2020.[66]

| Declared reserves with suspicious increases (in billion of barrels) Colin Campbell, SunWorld, 80-95 | |||||||

| Year | Abu Dhabi | Dubai | Iran | Iraq | Kuwait | Saudi Arabia | Venezuela |

| 1980 | 28.00 | 1.40 | 58.00 | 31.00 | 65.40 | 163.35 | 17.87 |

| 1981 | 29.00 | 1.40 | 57.50 | 30.00 | 65.90 | 165.00 | 17.95 |

| 1982 | 30.60 | 1.27 | 57.00 | 29.70 | 64.48 | 164.60 | 20.30 |

| 1983 | 30.51 | 1.44 | 55.31 | 41.00 | 64.23 | 162.40 | 21.50 |

| 1984 | 30.40 | 1.44 | 51.00 | 43.00 | 63.90 | 166.00 | 24.85 |

| 1985 | 30.50 | 1.44 | 48.50 | 44.50 | 90.00 | 169.00 | 25.85 |

| 1986 | 31.00 | 1.40 | 47.88 | 44.11 | 89.77 | 168.80 | 25.59 |

| 1987 | 31.00 | 1.35 | 48.80 | 47.10 | 91.92 | 166.57 | 25.00 |

| 1988 | 92.21 | 4.00 | 92.85 | 100.00 | 91.92 | 166.98 | 56.30 |

| 1989 | 92.20 | 4.00 | 92.85 | 100.00 | 91.92 | 169.97 | 58.08 |

| 1990 | 92.20 | 4.00 | 93.00 | 100.00 | 95.00 | 258.00 | 59.00 |

| 1991 | 92.20 | 4.00 | 93.00 | 100.00 | 94.00 | 258.00 | 59.00 |

| 1992 | 92.20 | 4.00 | 93.00 | 100.00 | 94.00 | 258.00 | 62.70 |

| 2004 | 92.20 | 4.00 | 132.00 | 115.00 | 99.00 | 259.00 | 78.00 |

| 2007 | ? | ? | 136.30 | 115.00 | 101.50 | 262.30 | 80.00 |

The world's total declared reserves are 1.3174 trillion barrels (January 2007).[citation needed] The years 2004 and 2007 were added later. Some figures from the year 2007 are missing because these are from a listing in the Oil and Gas Journal from dec. 2006, which listed only the top ten suppliers.

The table suggests that, firstly, the OPEC countries declare that the discovery of new fields, year after year, replaces exactly or near exactly the quantities produced, because the declared reserves do not vary a lot from one year to the other. For example, Saudi Arabia extracted 9.55 million barrels per day (1.518×106 m3/d) in 2005, i.e. 3.4 billion barrels per year (540×106 m3/a). Yet, their stated reserves do not decline, implying that they discover previously unknown reserves of exactly this amount, year after year. Abu Dhabi, in the United Arab Emirates, declares exactly 92.3 billion barrels (14.67×109 m3) since 1988, but in 16 years, 14 billion barrels (2.2×109 m3) were extracted.[citation needed]

Also, there is much competition between states. For example, Kuwait gave to themselves 90 billion barrels (14×109 m3) of reserves in 1985, the year of the reserves link. Abu Dhabi and Iran responded with slightly higher numbers, to guarantee similar production quotas. Iraq replied with around 100. Apparently, with all this amount of inflation, Saudi Arabia was forced to reply, two years later, with its own revision.[citation needed]

Other examples suggest the inaccuracy of official reserve estimates:

- January 2006, the magazine Petroleum Intelligence Weekly declared that reserves of Kuwait were in fact only 48 billion barrels (7.6×109 m3), of which only 24 Gbbl (3.8×109 m3) were "completely proven", backing this statement on "leaks" of official confidential Kuwaiti documents. The value is half of the official estimate.[66]

- Shell company announced 9 January 2004 that 20% of its reserves had to pass from proven to possible (uncertain). This announcement led to a loss in the value of the stock; a lawsuit challenged that the value of the company was fraudulently overvalued. Shell later revised its reserves estimates three times, reducing them by 10.133 billion barrels (1.6110×109 m3) (against 14.5 Gbbl (2.31×109 m3)*). Shell's president, Phil Watts, resigned.

- As can be seen on the table the reserves declared by Kuwait before and after the Gulf War 1990-1991 are the same, 94 billion barrels (14.9×109 m3), despite the fact that immense oil-well fires ignited by the Iraqi forces had burned off approximately 6 billion barrels (950×106 m3).[citation needed]

- In 1970, Algeria increased its "proven reserves" estimate (until then 7–8 Gbbl (1.1×109–1.3×109 m3)*) to 30 billion barrels (4.8×109 m3). Two years later, the estimate was increased to 45 billion barrels (7.2×109 m3). After 1974, the country's estimate was less than 10 billion barrels (1.6×109 m3) (as reported by Jean Laherrère).

- Pemex (state company of Mexico) in September 2002 decreased its reserve estimate by 53%, from 26.8 to 12.6 billion barrels (4.26×109 to 2.00×109 m3). Later the estimate was increased to 15.7 billion barrels (2.50×109 m3).

- Other examples exist of reserves being underestimated. In 1993, the reserves of Equatorial Guinea were limited to some insignificant fields; the Oil And Gas Journal estimated them at 12 million barrels (1.9×106 m3). Two giant fields and several smaller ones were discovered, but the numbers announced stayed unchanged until 2003. In 2002, the country still had 12 million barrels (1.9×106 m3) of reserves according to the journal, while it was producing 85 million barrels (13.5×106 m3) in the same year. The reserves of Angola were at 5.421 billion barrels (861.9×106 m3), (four significant numbers, it gives the impression of great precision) from 1994 to 2003, despite the discovery of 38 new fields of more than 100 million barrels (16×106 m3) each.

Note however that the definition of proven reserves varies from country to country. In the USA, the conservative rule is to classify as proven only the reserves that are being produced[cn]. On the other hand, Saudi Arabia classifies as proven reserves known fields not yet in production[cn]. Venezuela includes non-conventional oil (bitumens) of the Orinoco in its reserve base.

2020 Vision

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) reduced their forecast for Saudi Arabia oil production to 15.4 million barrels per day (2.45×106 m3/d) in 2020 and Middle East OPEC countries increasing to 35.2 million barrels per day (5.60×106 m3/d) by 2020 from 20.7 million barrels per day (3.29×106 m3/d) in 2002.[citation needed] These estimates were further reduced in the 2006 Annual Energy Outlook, in which Middle East OPEC production was projected to be 29.4/27.0/18.5 million barrels a day in 2020 assuming $34/$51/$85 oil prices respectively.[citation needed]

Strategic oil reserves

Many countries maintain government-controlled oil reserves for both economic and national security reasons. Although there are global strategic petroleum reserves, the following highlights the strategic reserves of the top three oil consumers.

The United States maintains a Strategic Petroleum Reserve at four sites in the Gulf of Mexico, with a total capacity of 727 million barrels (115.6×106 m3) of crude oil. The sites are enormous salt caverns that have been converted to store crude oil. The US SPR has never been filled to capacity; the largest amount reached thus far was 700 million barrels (110×106 m3) on August 17, 2005, whereafter reserves were drawn down to meet demand in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. This reserve was created in 1975 following the 1973–74 oil embargo, and as of 2005 it is the largest emergency petroleum supply in the world. At current US consumption rates (over 7 billion barrels (1.1×109 m3) per year), the SPR would supply all normal US demand for approximately 37 days. However, the maximum total withdrawal capability from the United States Strategic Petroleum Reserve is only 4.4 million barrels (700,000 m³) per day[citation needed], which would not be sufficient to fulfill the normal daily US demand.

In 2004 China's National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) began development on a 101.9 million barrels (16.20×106 m3) strategic reserve.[74] This strategic reserve plan calls for the construction of four storage facilities. An updated strategic reserve plan was announced in March 2007 for the construction of a second strategic reserve with an additional 209.44 million barrels (33.298×106 m3).[75] Separately, Kong Linglong, director of the National Development and Reform Commission's Foreign Investment Department, said that the Chinese government would soon move to establish a government fund aimed at helping its state oil groups purchase offshore energy assets.

As of 2003 Japan has a SPR composed of the following three types of stockpiles; state controlled reserves of petroleum composed of 320 million barrels (51×106 m3), privately held reserves of petroleum held "in accordance with the Petroleum Stockpiling Law" of 129 million barrels (20.5×106 m3), privately held reserves of petroleum products for another 130 million barrels (21×106 m3).[76] The state stockpile equals about 92 days of consumption and the privately held stockpiles equal another 77 days of consumption for a total of 169 days or 579 million barrels (92.1×106 m3).[77][78]

OPEC countries

Many countries with extensive oil reserves are members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC. The members of the OPEC cartel hold about two-thirds of the world's oil reserves, allowing them to significantly influence the international price of crude oil.

See also

- Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas

- Energy security

- Global strategic petroleum reserves

- Non-conventional oil

- Oil exploration

- Oil Megaprojects

- Oil price increases since 2003

- Peak Oil

- Petroleum Industry

- Strategic Petroleum Reserve

- World energy resources and consumption

Notes

- ^ "Glossary". U.S. Energy Information Agency. 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ^ WEC (2007), p. 41

- ^ "Proven Oil Reserves". moneyterms.co.uk. 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ^ "Oil Reserves". BP Global. 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ^ David F. Morehouse (1997). "The Intricate Puzzle of Oil and Gas Reserves Growth" (PDF). U.S. Energy Information Administration. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Petroleum Reserves Definitions" (PDF). Petroleum Resources Management System. Society of Petroleum Engineers. 1997. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- ^ a b c "Oil Reserves - Supply". Oil Market Report. OECD/International Energy Agency. 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ^ a b c "Glossary of Terms Used in Petroleum Reserves/Resources" (PDF). Society of Petroleum Engineers. 2005. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- ^ a b "Petroleum Resources Management System". Society of Petroleum Engineers. 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- ^ Alboudwarej; et al. (Summer 2006). "Highlighting Heavy Oil" (PDF). Oilfield Review. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Hyne, Norman J. (2001). Nontechnical Guide to Petroleum Geology, Exploration, Drilling and Production. PennWell Corporation. pp. pp.431-449. ISBN 918-0-87814-823-3.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check|isbn=value: invalid prefix (help) - ^ Lyons, William C. (2005). Standard Handbook Of Petroleum & Natural Gas Engineering. Gulf Professional Publishing. pp. pp.5-6. ISBN 0750677856, 9780750677851.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ E. Tzimas, (2005). "Enhanced Oil Recovery using Carbon Dioxide in the European Energy System" (PDF). European Commission Joint Research Center. Retrieved 2008-08-23.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Green, D W (2003). Enhanced Oil Recovery. Society of Petroleum Engineers. ISBN 978-1555630775.

- ^ "World Proved Reserves of Oil and Natural Gas". US Energy Information Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

- ^ U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) - U.S. Government - U.S. Dept. of Energy, EIA - Petroleum Data, Reports, Analysis, Surveys

- ^ "Saudi Arabia Oil Statistics". Country Analysis Briefs. US Energy Intelligence Administration. August 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ^ a b

Farsalas, Ken (2008-07-29). "No Speculation On Oil Reality". Forbes.com. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Petroleum (Oil) Production", International Petroleum Monthly, U.S. Energy Information Administration, April 2008, retrieved 2008-05-14

- ^

Tverberg, Gail (2008-01-18). "President Bush Questions Saudi Ability to Raise Oil Supply". PRWeb. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Penketh, Anne (2008-06-16). "Saudi King: 'We will pump more oil'". The Independent. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "New study raises doubts about Saudi oil reserves". Institute for the Analysis of Global Security. 2004-03-31. Retrieved 2008-07-30. Cite error: The named reference "iags" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ EIA (2007). "International Energy Outlook 2007". Energy Information Administration of the U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ a b c EIA (2007). "Country Analysis Brief: Canada". U.S. Energy Information Administration. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^

USask (2006). "Canadian frontier petroleum" (DOC). University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ NEB (May 2008). "Canadian Energy Overview 2007". National Energy Board of Canada. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ^ EIA (2007-12-28). "Crude Oil and Total Petroleum Imports Top 15 Countries October 2007 Import Highlights: Released on December 28, 2007". Energy Information Administration of the U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 55 (help) - ^ a b c d ERCB (2008). "ST98: Alberta's Energy Reserves 2007 and Supply/Demand Outlook 2008-2017". Alberta Energy Resources Conservation Board. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^

Cross, Philip (September 2006). "The Alberta economic juggernaut" (PDF). Canadian Economic Observer. Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ NEB (July 2007). "Capacity constraints coming". 2007 Canadian Hydrocarbon Transportation System Assessment. National Energy Board of Canada. Retrieved 2007-08-14.

- ^ NEB (6 May 2008). "Surging crude oil prices sparked a jump in applications for oil pipelines in 2007". National Energy Board of Canada. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ^ Clavet, Frederic (February 2007). "Canada's Oil Extraction Industry: Industrial Outlook, Winter 2007". The Conference Board of Canada. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- ^ a b "Iran Oil". Country Analysis Briefs. US Energy Information Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- ^ "Iran". The World Factbook. US Central Intelligence Agency. 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ^ a b "Iraq Oil". Country Analysis Briefs. US Energy Information Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- ^ Gal Luft (2003). "How Much Oil Does Iraq Have?". The Brookings Institution. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Kuwait Oil". Country Analysis Briefs. US Energy Information Administration. 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- ^ "United Arab Emirates Oil". Country Analysis Briefs. US Energy Information Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- ^ a b "Venezuela Oil". Country Analysis Briefs. US Energy Information Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- ^ Matthew Walter (2007-10-07). "Venezuela's Proven Oil Reserves Rise to 100 billion barrels (16×109 m3)". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Russia - Oil". Country Analysis Briefs. US Energy Information Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ^ "'Threat' to future of Russia oil". BBC News. 2008-04-15.

- ^ "Russia - Oil Exports". Country Analysis Briefs. US Energy Information Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ^ Elder, Miriam (2008-05-15). "Russian leaders pledge to stimulate oil production". International Herald Tribute. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ The Oil Drum | Uncertainties About Russian Reserves and Future Production

- ^ "Libya - Oil". Country Analysis Briefs. US Energy Information Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ^ "Nigeria - Oil". Country Analysis Briefs. US Energy Information Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ^ U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) - U.S. Government - U.S. Dept. of Energy. http://www.eia.doe.gov/oil_gas/natural_gas/data_publications/crude_oil_natural_gas_reserves/cr.html Total U.S. Proved Reserves of Crude Oil 1996-2006], Released Date: December 31, 2007

- ^ U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) - U.S. Government - U.S. Dept. of Energy, U.S. Petroleum Supply and Consumption 2005-2009, Date Published : July 8, 2008

- ^

Energy Information Agency, (EIA) (07/23/2008). "Crude Oil Production". U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

Energy Information Agency, (EIA) (07/23/2008). "Crude Oil Production". U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Annual Energy Review (AER)". Official Energy Statistics from the U.S. Government. U.S. Energy Information Administration. April 24, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-14.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Energy Information Agency, (EIA) (2007). "Petroleum Basic Statistics". U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ^ a b U.S. Department of the Interior, (MMS) (2006). "Assessment of Undiscovered Technically Recoverable Oil and Gas Resources of the Nation's Outer Continental Shelf, 2006" (PDF). Minerals Management Service. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- ^ a b U.S. Department of the Interior, (USGS) (2007). "Comprehensive Resource Summary: Conventional, Continuous, Coal-bed Gas" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- ^ Energy Information Agency, (EIA) (2006). "Crude Oil and Natural Gas Exploratory and Development Wells, Selected Years, 1949-2005" (PDF). U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ a b

U.S. Department of the Interior, (USGS) (April 10, 2008). "Comprehensive Resource Summary: Conventional, Continuous, Coal-bed Gas". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ United States Geological Survey, (USGS) (April 1998). "Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, 1002 Area, Petroleum Assessment, 1998, Including Economic Analysis". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ^ Energy Information Agency, (EIA) (May 2008). "Analysis of Crude Oil Production in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge" (PDF). U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ^ United States Geological Survey, (USGS) (2002). "U.S. Geological Survey 2002 Petroleum Resource Assessment of the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska (NPRA)". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ^ John R. Dyni (2005). "Geology and Resources of Some World Oil-Shale Deposits" (PDF). Scientific Investigations Report 2005–5294. US Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ^ a b c "Mexico - Oil". Country Analysis Briefs. Energy Information Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ a b "Mexico's Pemex says year-end oil output to miss goal". Reuters. July 30, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- ^ "Mexico says reform won't reverse oil woes fast". Reuters. July 29, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^

Parker, Alexandra S. (2003). "Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX): Lack of Fiscal Autonomy Constrains Production Growth and Raises Financial Leverage" (PDF). Report Number: 77084. Moody's Investor Service - Global Credit Research. Retrieved 2007-11-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c "Mexico oil output drop may spark crisis". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2007-06-14. Retrieved 2008-01-05. Cite error: The named reference "greenspan" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^

United States Geological Survey, (USGS) (July 27 2008). "90 Billion Barrels of Oil and 1,670 Trillion Cubic Feet of Natural Gas Assessed in the Arctic". USGS. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ [1], The New York Times, 24 July 2008

- ^ Alan Bailey (October 21, 2007). "USGS: 25% Arctic oil, gas estimate a reporter's mistake". Vol. Vol. 12, No. 42. Petroleum News. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

{{cite news}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Jaremko, Gordon (April 4, 2008). "Arctic fantasies need reality check: Geologist knows risks of northern exploration". The Edmonton Journal. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ^ Overlooking the world's largest island, The Copenhagen Post, 17 April 2008

- ^ Greenland Makes Oil Companies Melt, Terra Daily, 16 July 2006

- ^ "On Middle Eastern Oil Reserves". ASPO-USA's Peak Oil Review. February 20, 2006. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ^ China to have strategic oil reserve soon

- ^ "China to fill its 3rd strategic oil reserve". Times of India. 2007-03-08.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ The Oil Situation after the Attack on Iraq

- ^ "Energy Security in East Asia". Institute for the Analysis of Global Security. 2004-08-13.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Energy Security Initiative" (PDF). Asia Pacific Energy Research Center. 2002-01-01.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

References

- Adams Neal, Terrorism & Oil (2002, pg.66), ISBN 0-87814-863-9

- Various, The Oil Industry of the Former Soviet Union: Reserves, Extraction, Transportation (1998, pg. 24-59), ISBN 90-5699-062-4

- Robert J Art, Grand Strategy for America (2003, pg.62), ISBN 0-8014-4139-0

- Paul Roberts, "The End of Oil", (2004 p47-p52), Bloomsbury, pbk, ISBN 0-7475-7081-7

- Survey of energy resources (PDF) (21 ed.). World Energy Council (WEC). 2007. p. 586. ISBN 0 946121 26 5. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- Matthew R. Simmons (2006). Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy. Wiley. p. 464. ISBN 978-0471790181.

External links

- OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin.

- Energy Supply page on the Global Education Project web site, including many charts and graphs on the world's energy supply and use.

- Proyecto Ku-Maloob-Zaap, en la Sonda de Campeche.

- TrendLines' current Peak Oil Depletion Scenarios Graph, a monthly compilation update of 17 recognized estimates of URR, Peak Year & Peak Rate.

- U.S. Department of Energy Office of Fossil Energy information on managed reserves.

- Discusses Peak Oil implications.

- Peak Oil and Permaculture, Energy Bulletin, an interview with David Holmgren.

- Oil And The Future, by Richard Reese, 1997.

- "How Much Oil Does Iraq Have?" by Gal Luft, Co-Director, Institute for the Analysis of Global Security (IAGS), May 12, 2003.

- New study raises doubts about Saudi oil reserves, by the Institute for the Analysis of Global Security, March 31, 2004.

- Will The Proved Reserve Scandal Open The Door To Genuine Data Reform?, Reserve Reporting Conference, Matthew R. Simmons, April 14, 2004.

- Whose Reserves Estimates Can I Trust? - World Energy Magazine, Vol. 7 No. 1.

- Reserves and Fishing, World Energy magazine, Vol. 7 No. 2.

- U.S. Department of Energy International Energy Outlook July 2005.

- Kuwait oil reserves only half official estimate-PIW, Reuters, January 20, 2006.

- U.S. Department of Energy Annual Energy Outlook 2006.