Azerbaijanis in Armenia

The Azerbaijanis in Armenia ( Azerbaijani Ermənistan azərbaycanlıları or Qərbi azərbaycanlılar , "West Azerbaijanis") were citizens of the Soviet Union with Azerbaijani origin and Azerbaijani mother tongue, who lived in the Armenian Socialist Soviet Republic and traditionally were mostly Shiites . In 1979 over 160,000 people in the Armenian SSR - a good 5% of the population - declared themselves to be Azerbaijanis , making them the largest minority in Armenia. Between 1988 and 1991, at the beginning of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict , almost all of them left Armenia for Azerbaijan - similar to what the Armenians did in Azerbaijan in the opposite direction . According to UNHCR , in 2004 the number of Azeris in what is now the Republic of Armenia ranged from around 30 to a few hundred people, most of them in mixed marriages or in old age. Almost all of them have changed their names in order not to be recognizable as Azeris.

history

For centuries, Transcaucasia had an ethnically mixed population, both in what is now Armenia and Azerbaijan. While there has been an Armenian population in the region since ancient times - Christianized since the 4th century - the Turkic-speaking population goes back to the conquest of the Seljuk Turks in the 11th century, as a result of which Iranian old Azerbaijani , which was probably predominant here, is replaced by today's as The Turkic language called Azerbaijani was superseded and Shiite Islam prevailed against the Zoroastrianism previously practiced here . Christian Armenians predominated in the region until the middle of the 14th century, but with Timur's conquests at the latest , Muslims became the majority population. However, there was a strong and continuous Armenian presence with the Christian principalities of the Armenian Meliks in Nagorno-Karabakh, which existed until the 18th century .

Around 1800 lived in what was then Iranian Armenia, which in addition to Yerevan also comprised Nachivan , Gangia (later Yelisawetpol) and all of today's Azerbaijan between Kura and Arax ( i.e. excluding the east around Baku on the Caspian Sea, then Shirvan ), according to estimates about 20 % Armenian Christians and 80% Shiite Muslims. The Persian surveys only took into account the religion and not the language, so that the number of Armenians could be recorded through the membership of the Armenian Apostolic Church , while the Muslims were not differentiated into Turkic speakers , Persian speakers or Talish .

Through the treaties of Gulistan in 1813 and Turkmentschai in 1828, Persia lost the areas north of the Arax - Chirvan with Baku and Iranian Armenia - as well as Talisch (formerly northeast Aderbeitzan) on the Caspian Sea, south of Arax and Kura, to Russia, so that for the first time the Turkish-speaking population there lived partly under Russian, partly still under Persian rule. As a result, many Armenians emigrated from the still Persian areas, but also from Turkish Armenia to Russian Armenia, while Muslims took the opposite route. As a result, in the Armenian Oblast , which comprised larger parts of present-day Armenia with Yerevan, Nakhichevan and Igdir and was reorganized into Gubernija Yerevan in 1840 , the Armenians were soon again in the majority. Language was also recorded in the Russian censuses. In the Russian Empire , the Turkic-speaking Shiites of the Caucasus region were called Tatars (татары), while after the October Revolution of 1917 the name Azerbaijanis (азербайджанцы, azərbaycanlılar ) or Azeris ( azərilər ) was introduced. The Armenians, on the other hand, usually referred to the Azeris as "Turks" or "Eastern Turks". Transcaucasia had a mixed population in terms of religion and language, whereby according to the 1897 census in the Gubernija Yerevan the Armenians, in the Gubernija Jelisavetpol and the Gubernija Baku the Tatars (according to today's understanding the Azeris) formed the majority. At the turn of the century there were around 300,000 Tatars in the Gubernija Yerevan, making up 37.5% of the population. For example, while in Shusha in Nagorno-Karabakh in Gubernija Yelisawetpol with its 25,656 inhabitants, according to the Russian encyclopedia Brockhaus-Efron, at the turn of the century there was an Armenian majority of 56.5% versus 43.2% Tatars, there were around 29,000 inhabitants in the Armenian capital Yerevan including 49% Tatars, 48% Armenians and 2% Russians. In addition to 2 Orthodox and 6 Armenian Apostolic Churches, there were 7 Shiite mosques in the city, but none of them Sunni.

According to the Caucasus researcher Thomas de Waal , the 20th century was a period of marginalization, discrimination, mass and often forced migration for Azerbaijanis in Armenia. Most of the Tatars lived in rural areas from agriculture or carpet weaving . Almost all of them were Shiites , but mainly around Talin , but also in Shirak and on Wedi, there were Sunnis . Luigi Villari reported in 1905 that the Tatars in Yerevan were generally more wealthy than the Armenians and owned almost all of the land.

Relations between Christian Armenians and Muslim Tartars were widespread and, in the course of the Russian Revolution of 1905, culminated in the Armenian-Tatar massacres that lasted until 1907 , in which 128 Armenian and 158 Tatar villages were destroyed or looted and around 3,000 to 10,000 people died, whereby the number of victims on the part of the poorly organized Tatars was higher.

Democratic Republic of Armenia

The Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan and the Democratic Republic of Armenia waged war against each other from 1918 to 1921 over the regions of Nakhichevan , Sangesur ( Syunik ), the area around Gazach and Karabakh , all of which had a mixed population of Armenians and Azerbaijanis. In 1920 the 11th Red Army conquered the area. In the agreements of Moscow (March 16, 1921) and Kars (October 23, 1921) between the Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic and Turkey , the affiliation of the Ujezd Nakhichevan and the neighboring Bash-Norashen to Azerbaijan was established. Karabakh was also added to Azerbaijan, while Sangesur (Sjunik), which was held by Armenian rebels as the Republic of Mountain Armenia from February to July 1921 , came to Soviet Armenia .

As a result of the Armenian genocide in the Ottoman Empire and the advance of the Turkish army in 1918, tens of thousands of Armenian refugees poured into the young Democratic Republic of Armenia. Other Armenians fled pogroms in Azerbaijan, for example in Baku in 1918 and in Shusha in 1920 . A large part of the Azerbaijanis in Armenia fled to Azerbaijan. The Armenian strategists Andranik Ozanian and Rouben Ter Minassian were entrusted with resettling Armenian refugees from western Armenia in former Tatar settlements in eastern Armenia. Andranik was known from mid-1918 a. a. for the destruction of Muslim (Azerbaijani) settlements during the cleanup operations in the Armenian-Azerbaijani border region of Sangesur. Richard Hovannisian describes his actions as the beginning of the transformation of this region into a purely Armenian province. Azeris were, among others, from 20 villages in Yerevan and in Syunik sold. Ter Minassian, according to the French historian Anahide Ter Minassian (his daughter-in-law), used bargaining and intimidation tactics, but primarily fire and steel, and violent methods to "encourage" Muslims to leave Armenia. In his report from June 1919, Anastas Mikoyan warned that “the organized extermination of the Muslim population in Armenia could at any time lead to a war with Azerbaijan”.

Of the 80 members of the Armenian Parliament, 3 were Azerbaijanis. In the face of the war against Azerbaijan, they were viewed with the greatest suspicion.

Armenian SSR

Some of the displaced or fled Azeris returned to Armenia after the establishment of Soviet rule. According to the Soviet census of 1926, 84,705 Azeris lived in the Armenian SSR, which made up 9.6% of the population. In 1939 there were 131,896 Azeris in Armenia.

From 1934 to 1944, the singer Rashid Behbudov was a soloist with the Yerevan Philharmonic and the Armenian State Jazz Orchestra. In addition, he performed at the Armenian National Academic Theater of Opera and Ballet. The theater and film critic Sabir Rzayev, an ethnic Azeri from Yerevan, was the founder of the Armenian Film Studios and author of the first and only monograph on films in Soviet Armenia.

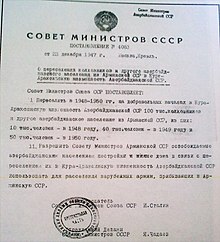

After the Second World War , the leadership of the Armenian SSR tried to bring Armenians from the diaspora to Soviet Armenia. Tens of thousands of Armenians from Syria (including the family of the later President Levon Ter-Petrosyan ), Iraq and Iran followed the call until the early 1950s. In 1947, Grigor Harutjunjan , the First Secretary of the CPSU in the Armenian SSR, succeeded in convincing the Council of Ministers of the USSR to create settlement space for the newcomers in Soviet Armenia by relocating Azerbaijanis from Armenia to Azerbaijan . The Council of Ministers adopted a "Decree on the resettlement of collective farmers and other Azerbaijani population from the Armenian SSR to the Kura-Aras lowlands of the Azerbaijan SSR" ( Указ о переселении колхозников и другого азербайджанского населения из Армянской Soviet Socialist Republic в Кура-Араксинскую низменность Азербайджанской ССР) . On the basis of the decree, between 1948 and 1951, around 100,000 Azerbaijanis were resettled from Armenia on a “voluntary basis” to central Azerbaijan. Today, official Azerbaijani authorities refer to the resettlement as compulsory “ deportation ”. According to the official census of 1959, the number of Azeris in Soviet Armenia was only 107,748. In Yerevan , the Azeris only made up 0.7% of the population in 1959. According to the 1979 census, 160,841 Azeris, 5.3% of the population, lived in Soviet Armenia. The Azerbaijanis in Armenia formed the largest ethnic minority in the Armenian SSR in the 1980s.

The Azeris in the Armenian SSR were particularly active in agriculture and the food trade and therefore had a great influence on the Green Bazaar , which led to conflicts with the Armenian majority population when food was scarce.

The Soviet authorities enabled the Azeris in Armenia to attend schools with Azerbaijani as the language of instruction until the end of the Soviet Union. Of the 160,841 Azeris in Armenia in 1979, 16,164 (10%) spoke Armenian and 15,879 (9.9%) Russian as a second language.

In the urban milieu of Yerevan there were more ethnically mixed Azerbaijani-Armenian marriages, from which Russian-speaking families emerged. Most of the Azerbaijani students in Yerevan attended Russian-speaking schools . The Azeris in Yerevan lived together peacefully with their Armenian neighbors, and adults and children had no language barriers due to the common Russian language, as was the case with the Azeris and Armenians in Baku .

Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

In 1987, the Armenian leadership of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast demanded affiliation with the Armenian SSR. This was rejected by both the Azerbaijani SSR leadership and the Soviet Union in Moscow. This was followed by demonstrations, first in Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia, and later in the opposite direction in Azerbaijan. In both Armenia and Azerbaijan there was violence against the respective minority populations.

On January 25, 1988, the first wave of Azerbaijani refugees from Armenia reached the city of Sumgait . At the end of February 1988 there was the pogrom in Sumgait , in which Azeris who had fled Armenia played a major role and in which, according to official information, 26 Armenians and six Azeris, but probably up to 200 people, were killed. This led to a mutual mass exodus from the two countries. On March 23, 1988, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR finally rejected Nagorno-Karabakh's demands for annexation to Armenia. Soviet troops were stationed in Yerevan. There were attacks on Azeris in other Armenian locations. In Ararat Raion , four Azeri villages were burned on March 25, 1988. On May 11th, after violent clashes, numerous Azeris fled from Ararat Oblast to Azerbaijan. On June 7, 1988, the Azeris were expelled from the city of Masis on the Armenian-Turkish border, and on June 20, 1988 from 5 other Azeri villages in Ararat Rajon. Another wave of refugees from Azeris from Armenia followed in November 1988, which also resulted in deaths. According to Armenian sources, 25 Azeris died, 20 of them in Gugark in Lori Province . Azerbaijani authorities, on the other hand, spoke of 217 Azeris killed.

However, even during this time of nationalist tension there were cases of cooperation. In 1988, Azeris in Yerevan and Armenians in Baku organized the exchange of apartments, as they felt that the time of multicultural coexistence was coming to an end and a self-organized population exchange took place.

In the years from 1988 to 1991, almost all of the remaining Azeris from Armenia fled to Azerbaijan, around the same time that the last Armenians fled to Armenia from the areas of Azerbaijan not controlled by the Karabakh Armenians. The number of Azeris who fled Armenia is difficult to determine, since the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict was already in full swing when the USSR was last census in 1989. The share of the once numerous Azeris in Yerevan in 1989 was only 0.1%. UNHCR estimates that almost 200,000 Azeris lived in Armenia in 1988 and almost completely fled to Azerbaijan during the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. In addition to these numbers, there are also Muslims who have fled Armenia and who were not Azeris. The Azerbaijani authorities have mutually called different numbers from 200,000 to 250,000, but they tend, for political reasons to them with the IDPs from Nagorno-Karabakh to be combined and the surrounding areas, so a number of over one million refugees and IDPs in Azerbaijan to come - an amount that is denied by the experts and is more likely to be roughly 800,000 people, of which around 570,000 are internally displaced.

Current status in the Republic of Armenia

The historian Suren Hobosjan from the Armenian Institute of Archeology and Ethnography estimated the number of people of Azerbaijani origin in Armenia at 300 to 500 people, mostly descendants of mixed marriages and only around 60 to 100 with entirely Azerbaijani origin. In an anonymous case study of 15 people with Azerbaijani ancestry (13 with mixed Armenian-Azerbaijani ancestry and 2 with full Azerbaijani ancestry) conducted in 2001 by the International Organization for Migration with the support of the Armenian Sociological Association in Yerevan, Meghri, Sotq (formerly Zod) and Avazan (formerly Göysu) told 12 respondents that they hid their Azerbaijani roots as much as possible in public, and only 3 claimed to be Azeri. 13 out of 15 respondents described themselves as Christians and none as Muslim. According to official figures from 2001, 29 Azeris lived in Armenia. Hranush Kharatyan , head of the Department for National Minorities and Religious Affairs of the Republic of Armenia, stated in February 2007 that there are still ethnic Azerbaijanis in Armenia. She knows many of them, but cannot give any figures. Since Armenia has signed a corresponding UN convention, the state is not allowed to publish statistical information on groups at risk. Some were reluctant to talk about their origins, while others were more likely to do so. She spoke to some Azeris in Armenia who, however, did not yet have the will to form an ethnic community.

Cultural heritage

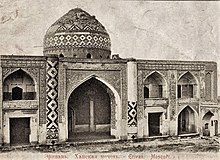

According to the "Caucasian Calendar" (yearbook) of the Russian Namestnik (наместник) of Transcaucasia for the year 1870, there were 269 Shiite mosques in Gubernija Yerevan. According to the Russian encyclopedia Brockhaus-Efron, there were 2 Orthodox and 6 Armenian Apostolic churches in the capital Yerevan, 7 Shiite mosques, but no Sunni mosques.

According to Ivan Ivanovich Schopen (Иван Иванович Шопен, 1798–1870) there were eight mosques in Yerevan (in addition to 6 Armenian Apostolic churches) in the middle of the 19th century:

- Abbas Mirza Mosque (in Yerevan Fortress)

- Mohammad Khan Mosque (inside Yerevan Fortress)

- Zali Khan Mosque

- Shah Abbas Mosque

- Novruz Ali Beg Mosque

- Sartip Khan Mosque

- Blue Mosque

- Hajji Imam Wardi Mosque

- Haji Jafar Beg Mosque (Haji Nasrollah Beg)

After Yerevan was annexed to the Russian Empire in 1828, the main mosque in the Yerevan Fortress, built by the Turks in 1582, was converted into an Orthodox church on the orders of the Russian general Ivan Paskevich and consecrated as the Church of the Intercession of Our Lady on December 6, 1827.

Under Josef Stalin , most mosques, but also churches in the city of Yerevan were demolished and replaced by secular buildings in the 1930s.

After almost all Muslims left Armenia during the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict from 1988 to 1994, the remaining mosques became orphaned. Traces of the former Muslim or Azerbaijani presence were more or less removed. Thomas de Waal , for example, reports on a small mosque on Vardanants Street in the center of Yerevan, which was bulldozed after the Muslim believers fled the city around 1990 and which is not mentioned in the city. De Waal recognized the vacant lot and asked a neighbor who remembered. Such destruction was justified by the fact that the Azeris did the same with the Armenian churches in Azerbaijan. For example, the Armenian sociologist Lyudmila Harutjunjan is quoted as saying that the Armenians responded to acts of the Azeris against the Armenians with similar acts, but that the trauma of the genocide of the Armenians leaves no room for commemoration of these own acts.

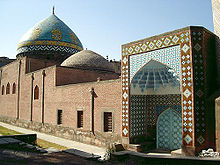

The only mosque still used as such today is the Shiite Blue Mosque in Yerevan, which served as a city museum in Soviet times. Like most mosques in Yerevan and all of Eastern Armenia, it was built during the time of Persian rule and is therefore also known as the "Persian Mosque of Yerevan". Since the Shiite believers who once came here were predominantly Turkic-speaking (ethnic Azeris), this designation is seen by the Azerbaijani side as a linguistic deletion of the Azerbaijani past, because it should actually be called "Azerbaijani mosque".

Individual evidence

- ↑ Second Report Submitted by Armenia Pursuant to Article 25, Paragraph 1 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities . Received on November 24, 2004

- ↑ a b c International Protection Considerations Regarding Armenian Asylum-Seekers and Refugees ( Memento of April 16, 2014 in the Internet Archive ). United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Geneva, September 2003.

- ↑ Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003: Armenia US Department of State. Released 25 February 2004

- ^ Robert Hewsen : Armenia: A Historical Atlas . Chicago University Press, Chicago 2001.

- ^ E. Yarshater: The Iranian Language of Azerbaijan. Encyclopædia Iranica, August 18, 2011.

- ^ CE Bosworth: Arran. Encyclopædia Iranica, August 12, 2011.

- ↑ Olivier Roy: The new Central Asia. IB Tauris, London 2007. ISBN 978-1-84511-552-4 , p. 6 .

- ↑ a b George A. Bournoutian: The population of Persian Armenia prior to and Immediately Following its annexation to the Russian Empire: from 1826 to 1832. The Wilson Center, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies, Washington 1980. pp. 11-14.

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen: The Kingdom of Arc'ax , in: Thomas J. Samuelian and Michael E. Stone (eds.): Medieval Armenian Culture . University of Pennsylvania Armenian Texts and Studies, Scholars Press, Chico (California) 1984. pp. 52-53. ISBN 0-89130-642-0

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen: The Meliks of Eastern Armenia: A Preliminary Study. Revue des Études Arméniennes 9 (1972). Pp. 299-301.

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Black Garden - Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York University Press, 2003. p. 81.

- ↑ “We will exterminate you.” Pogroms in Sumgait and Baku. Der Spiegel, March 23, 1992.

- ↑ Первая Всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Под ред. Н.A.Tройницкого. т.II. Общий свод по Империи результатов разработки данных Первой Всеобщей переписи населении населения, населения населения, произведяния, произвед 18 .97. С.-Петербург, 1905. Таблица XIII. Распределение населения по родному языку, в: Первая всеобщая перепись населения Росисийской Импер.1897 Импер. Распределение населения по родному языку, губерниям и областям. В расположенном ниже списке выберите регион. Эриванская губерния. Демоскоп (Demoscope.ru), 2017.

- ↑ Брокгауз-Ефрон и Большая Советская Энциклопедия, объединенный словник: Эриванская губерния. Брокгауз-Ефрон , Санкт-Петербург, 1890–1907.

- ↑ Брокгауз-Ефрон и Большая Советская Энциклопедия, объединенный словник: Шуша. Брокгауз-Ефрон , Санкт-Петербург, 1890–1907.

- ↑ a b Брокгауз-Ефрон и Большая Советская Энциклопедия, объединенный словник: Эривань. Брокгауз-Ефрон , Санкт-Петербург, 1890–1907.

- ↑ Том де Ваал: Глава 5. Ереван. Тайны Востока. Главы из русского издания книги "Черный сад". July 8, 2005, Retrieved February 16, 2018 (Russian).

- ↑ А. А. Цуциев: Атлас этнополитической истории Кавказа. Издательство "Европа", Москва 2007.

- ^ Luigi Villari: Fire and Sword in the Caucasus. TF Unwin, London 1906. p. 267.

- ^ Svante Cornell: Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus, Taylor & Francis, London 2000. p. 69.

- ^ Tadeusz Swietochowski: Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. Columbia University Press, New York City 1995. ISBN 0-231-07068-3 , ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3

- ↑ Tobias Debiel, Axel Klein: Fragile Peace: State Failure, Violence and Development in Crisis Regions. Zed Books, London 2002, p. 94.

- ↑ Modern Hatreds: The Symbolic Politics of Ethnic War by Stuart J. Kaufman. Cornell University Press, 2001. p. 58. ISBN 0-8014-8736-6 .

- ^ Turkish-Armenian War: Sep. 24 - Dec. 2, 1920 by Andrew Andersen

- ^ Donald Bloxham: The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, pp. 103-105.

- ^ Donald Bloxham, The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism and the Destruction . Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. 103-105 .

- ↑ a b Thomas de Waal: Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014. p. 122.

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide . Oxford University Press, 2014, pp. 122 .

- ↑ Станислав Тарасов: ЗАЧЕМ АЗЕРБАЙДЖАНУ НОВАЯ «ИСТОРИЧЕСКАЯ РОДИНА». July 7, 2014, accessed February 16, 2018 (Russian).

- ↑ a b Arseny Sarapov: The Alteration of Place Names and Construction of National Identity in Soviet Armenia ( Memento of September 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ РГАЭ РФ (быв. ЦГАНХ СССР), фонд 1562, опись 336, ед.хр. 966-1001 (Разработочная таблица ф 15А Национальный состав населения по СССР , республикам, областям, районам..), В: Всесоюзная перепись населения 1939 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР: Армянская ССР. Демоскоп (Demoscope.ru), 2017.

- ↑ Իզաբելլա Սարգսյան [Isabella Sargsyan]: Հայկական կինոգիտության ադրբեջանցի հիմնադրի մասին և ոչ միայն. About the Azerbaijani founder of Armenian film and others. Epress. On October 15, 2014.

- ↑ Vladislav Zubok: Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev. UNC Press, 2007. ISBN 0-8078-3098-4 , A p. 58.

- ^ Anita LP Burdett: Armenia: Political and Ethnic Boundaries 1878-1948 ( Memento of September 26, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) ISBN 1-85207-955-X .

- ↑ Deportation of 1948–1953 . Azerbembassy.org.cn

- ^ A b c Lenore A. Grenoble: Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Springer, 2003, p. 135. ISBN 1-4020-1298-5 .

- ^ Hafeez Malik: Central Asia: Its Strategic Importance and Future Prospects. St. Martin's Press, 1994, p. 149. ISBN 0-312-10370-0 .

- ↑ РГАЭ РФ (быв. ЦГАНХ СССР), фонд 1562, опись 336, ед.хр. 1566а -1566д (Таблица 3,4 Распределение населения по национальности и родному языку), в: Всесоюзнаае9лености и родному языку . Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР: Армянская ССР. Демоскоп (Demoscope.ru), 2017.

- ↑ РГАЭ РФ (быв. ЦГАНХ СССР), фонд 1562, опись 336, ед.хр. 6174-6238 (Таблица 9с. Распределение населения по национальности и родному языку), в: Всесоьгная Всесоьзная перепа 1979. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР: Армянская ССР. Демоскоп (Demoscope.ru), 2017.

- ^ Jewish Post: Jewish Armenia

- ↑ Eva-Maria Also: "Eternal Fire" in Azerbaijan - A country between perestroika, civil war and independence. Reports of the Federal Institute for Eastern and International Studies, No. 8, 1992.

- ↑ Edmund Herzig, Marina Kurkchiyan: The Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity. Routledge, 2004. p. 216.

- ↑ Ronald Grigor Suny : Looking Toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History. Indiana University Press, 1993. p. 184.

- ↑ Vladimir Shlapentokh: A Normal Totalitarian Society: How the Soviet Union Functioned and How It Collapsed . ME Sharpe, Armonk (New York) 2001, p. 269.

- ↑ Иван Костянтыновыч Билодид [Ivan Kostyantynovich Bilodid]: Русский язык как средство межнационального общения as a means between the Russian language. Наука, Москва [Nauka, Moscow] 1977, p. 164.

- ↑ a b Günel Mövlud, Aziz Kerimov, Gayane Mkrtchian: Karabakh and the Ban on Memory. Meydan TV, December 15, 2016.

- ^ A b c Lowell Barrington: After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States. University of Michigan Press, 2006. ISBN 0-472-02508-2 , p. 230.

- ↑ a b Карабах: хронология конфликта . BBC Russian

- ↑ Arie Vaserman, Ram Ginat (1994): National, territorial or religious conflict? The case of Nagorno-Karabakh. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 17 (4), p. 348. doi: 10.1080 / 10576109408435961.

- ↑ Suha Bolukbasi: Azerbaijan: A Political History. IBTauris, 2011. ISBN 1-84885-620-2 . P. 97.

- ^ Svante E. Cornell: The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict. Department of East European Studies, Uppsala 1999. PDF archived ( Memento of April 18, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Погромы в Армении: суждения, домыслы и факты. Гарник Бадалян и Председатель КГБ Республики Армения генерал-майор Усик Суренович Арутюнян. Газета "Экспресс-Хроника", №16, April 16. 1991.

- ^ Azerbaijan State Commission On Prisoners of War, Hostages and Missing Persons

- ^ The Status of Armenians, Russians, Jews and Other Minorities. UNHCR, US Department of Homeland Security, Citizenship and Immigration Services Country Reports Azerbaijan.

- ↑ Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2004: Armenia. US Department of State

- ↑ Sergey Rumyansev: Refugees and Forced Migrants in Azerbaijan: the Political Context. CARIM-East Explanatory Note 13/115, Socio-Political Module, September 2013.

- ^ Selected Groups of Minorities in Armenia (case study). ASA / MSDP. Yerevan, 2001.

- ↑ How Many Azeris in Armenia. Armenia Today, January 11, 2011.

- ↑ Tatul Hakobyan: The Azerbaijanis Residing in Armenia Don't Want to Form an Ethnic Community. Hetq.am, February 26, 2007.

- ↑ Кавказский календарь на 1870 год. Типография Главного Управления Наместника Кавказского, Тифлис 1869, 392 pages.

- ↑ Иван Иванович Шопен: Исторический памятник состояния Армянской. Императорская Академия Наук, 1852. p. 468.

- ↑ George A. Bournoutian: The Khanate of Erevan under Qajar rule, 1795-1828. Mazda Publishers, 1992. ISBN 0-939214-18-0 , p. 173.

- ↑ Василий Александрович Потто: Кавказская война. Том 3. Персидская война 1826–1828 гг. MintRight Inc., 2000. ISBN 5-4250-8099-9 , p. 359.

- ^ Markus Ritter: The Lost Mosque (s) in the Citadel of Qajar Yerevan: Architecture and Identity, Iranian and Local Traditions in the Early 19th Century. Iran and the Caucasus 13 (2009), p. 244.

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Black garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War . New York University Press, New York 2003. p. 79.

- ^ Robert Cullen, A Reporter at Large: Roots . The New Yorker , Apr 15, 1991, p. 55.

- ^ A b Thomas de Waal: Black garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War . New York University Press, New York 2003. p. 80.