Armenians in Azerbaijan

The Armenians in Azerbaijan were citizens of the Soviet Union with Armenian origin and Eastern Armenian , but in the cities often Russian as their mother tongue, who lived in the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic and traditionally mostly belonged to the Armenian Apostolic Church . In 1979 there were about 475,500 people in the Azerbaijani SSR who declared themselves Armenians , about 7.9% of the population, of which 215,807 in the capital Baku , where they made up 14.1% of the population. There were also many Armenians in SumgaitWhere it was about one fifteenth, and in Kirovabad with 40,354 men and 17.5%. In the Autonomous Oblast of Nagorno-Karabakh in 1989 were of 187,769 inhabitants, 145,403 Armenians, ie 77.4%, while the north of that location Rajon Shaumyan almost armenischsprachig was. During the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict , several hundred Armenians were killed in the pogroms in Sumgait (1988), Kirowabad (1988) and Baku (1990). Between 1988 and 1994, almost all Armenians had to leave the area controlled by the Republic of Azerbaijan and found refuge in Armenia or the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh (now the Republic of Artsakh ) - similar to how, in the opposite direction, almost all Azerbaijanis were expelled from Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh . Of the 146,600 inhabitants of the Artsakh Republic according to the 2012 census, over 99% were Armenians. The number of Armenians in the territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan, on the other hand, was less than 3,000 people in 1999, the majority of whom were married to people of Azerbaijani ethnic identity or of mixed origin. In view of the officially propagated hostility towards Armenians , it is not possible in Azerbaijan today to reveal one's Armenian identity.

history

Before the October Revolution had the Russian Empire belonging Transcaucasia a polyethnic population, which according to census 1897 in the Gubernija Yerevan (to 1840 in 1828 Armenian Oblast ) the Armenians in the Gubernija Jelisawetpol and Gubernija Baku contrast татары the Tartars (, азербайджанцы after 1918, Azeris) formed the majority, while in the Gubernija Tbilisi the Georgians and in the Kars Oblast the Turks formed the strongest ethnic group.

From antiquity to the end of Persian rule in Transcaucasia

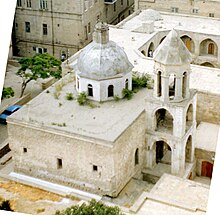

While there has been an Armenian population in the region since ancient times - Christianized since the 4th century - the Turkic-speaking population goes back to the conquest of the Seljuk Turks in the 11th century, as a result of which Iranian old Azerbaijani , which was probably predominant here, is replaced by today's as The Turkic language called Azerbaijani was superseded and Shiite Islam prevailed against the Zoroastrianism previously practiced here . Christian Armenians predominated in the region until the middle of the 14th century, but with Timur's conquests at the latest , Muslims became the majority population. In Baku, where an Armenian church was built around the year 500, there was still a predominantly Christian population in the 15th century. The region of Nagorno-Karabakh with its five Christian principalities (Meliktümern) of the Armenian Meliks , including the house of Hassan-Jalaljan von Chatschen (Greater Arzach ) , preserved its Christian-Armenian character most strongly . Among the latter, the Gandsassar Monastery was built in 1216 , which was the seat of the Catholic of Aghwank (Albania) from around 1400 until shortly after the Russian conquest in 1816.

Julfa , Armenian Jugha, first mentioned in the 5th century , was an important trading center in the Middle Ages, where both Muslims and Armenian Christians lived. With the wars between the Ottoman Empire and Persia under the Safavids in the 16th century, the city fell into disrepair. In 1604, Shah Abbas I had the city burned down, which he was unable to defend against the Turks, and the more than 20,000 inhabitants were forcibly relocated to the Persian metropolis of Isfahan , where the Armenians built a new district with 24 churches, which they called Nor Jugha ( New Culfa ) and that is still the residential area of the Isfahan Armenians today. Since then, no Armenians have lived in the old Armenian settlement area around Jugha am Arax, but the Armenian cemetery there testified to the Armenian past of the city until it was destroyed in 2005 .

Russian Empire

The ratio of the population in 1800 in the then Iranian-Armenia, in addition to Erivan also Nachivan , Gangia (later Jelisawetpol) and the whole Today Azerbaijan between Kura and Arax (without the East at Baku on the Caspian Sea, the former Shirvan ) included, is estimated to be 20% Armenian Christians and 80% Shiite Muslims. With the expansion of the Russian Empire , all areas of present-day Armenia and Azerbaijan were finally lost to Qajar Persia until 1828. As a result, many Armenians emigrated from the still Persian areas, but also from Turkish Armenia to Russian Armenia, while Muslims took the opposite route. As a result, in the Armenian Oblast, which comprised larger parts of today's Armenia with Yerevan as well as Nakhichevan and Igdir , the Armenians were soon again in the majority, while there were also strong Armenian minorities in the major cities of today's Azerbaijan such as Yelisavetpol and Baku. A focus of Armenian settlement was the mountainous parts of the former Karabakh Khanate - essentially the later Nagorno-Karabakh Oblast - where, according to a census from 1823, a large part of the villages or 97.5% of the rural population was Armenian. Fewer Armenians from Persia and Turkish Armenia immigrated to Nagorno-Karabakh than to Gubernija Yerevan. After all, three villages in Nagorno-Karabakh, in which special, Persian-influenced dialects are spoken - Maraga near Martakert (until the destruction in 1992) in the northeast, Melikjanlu and Tsakuri in the south - were founded by Armenian immigrants from Persia, while in the rest of Nagorno-Karabakh there have been Armenians since ancient times lived their traditional Karabakh dialect. The Armenian majority in the largest and most important city of Nagorno-Karabakh, Shusha , was less pronounced than in the surrounding rural areas , where, according to the 1897 census of the Russian Empire, of 25,881 inhabitants, 14,420 Armenians (55.7%), 10,778 Tatars (41.6%) and 359 Russians (1.4%) were. There was one Russian Orthodox and five Armenian Gregorian churches , two Shiite mosques , a secondary school, silk and cotton weaving, and significant trade. However, Yelisavetpol also had a strong Armenian minority, according to the 1886 census, it was 8914 people or 43.9%. In the Ujesd Nakhichevan within the Gubernija Yerevan, according to the 1897 census, the Tatars made up 57% of the population, while the Armenians made up 42%. In 1916 the proportion of Armenians in Nakhichevan was given as only 40%.

Relations between Christian Armenians and Muslim Tartars were widespread and, in the course of the Russian Revolution of 1905, culminated in the Armenian-Tatar massacres that lasted until 1907 , in which 128 Armenian and 158 Tatar villages were destroyed or looted and around 3,000 to 10,000 people died, whereby the number of victims on the part of the poorly organized Tatars was higher.

Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan

After the declaration of independence of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic in 1918, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaks) intensified its activities in the city of Baku, which was occupied by the Bolsheviks and where around 120,000 Armenians lived at that time. Many of the leading members of the Baku Commune Soviet were Armenians, including Chairman Stepan Shahumyan from Tbilisi . While the commune wanted to end the inter-ethnic violence, the Dashnaks took part in the March fighting in Baku in March 1918 , in which up to 12,000 Muslim residents and around 2,500 Armenian Christians were killed. In a decree of Azerbaijani President Heidar Aliyev from 1998, the massacres were described as “genocide against the Azerbaijanis” ( Mart soyqırımı , “March genocide”) and both the Armenians in Azerbaijan as a whole and the Baku commune were held responsible for them. Which stands the vote as a civil war between the Bolsheviks of Baku Commune and fighters of the pan-Turkic Musavat counter -party. After the city was captured by Turkish troops and the Baku Soviets fled, around 9,000 to 30,000 Baku Armenians were killed in the Armenian pogrom in Baku in 1918 , while others left the city in a panic. Nevertheless, eleven of the 96 members in the parliament elected on December 18, 1918 were ethnic Armenians, including Dashnaks.

The Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan and the Democratic Republic of Armenia waged war against each other from 1918 to 1921 over the regions of Nakhichevan , Sangesur ( Syunik ), the area around Gazach and Karabakh , all of which had a mixed population of Armenians and Azerbaijanis. In mid-June 1919, Armenia had the former Uezd Nakhichevan under its control, but by the end of July Azerbaijani troops retook the city of Nakhichevan.

In the days from June 5 to 7, 1919, Azerbaijani forces slaughtered around 600 to 700 residents in the Chaibalikend massacre after taking four Armenian villages in Nagorno-Karabakh. After the conquest of the nearby, mostly Armenian-populated city of Shusha in Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijani and Turkish troops destroyed the Armenian quarter of the city during the Shusha pogrom on March 22nd and 26th, 1920, killing most of the residents present. The death toll varies widely and is between 500 and 20,000 or 30,000. Some of the Armenians were able to flee; only a few surviving Armenians remained in the city.

Soviet rule

At the end of March 1920, Armenian forces regained control of the Nakhichevan and Sangesur regions, but in July 1920 the 11th Red Army took the area. In the treaties of Moscow (March 16, 1921) and Kars (October 23, 1921) between the Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic ( Soviet Russia ) and Turkey , the affiliation of the Ujezd Nakhichevan and the neighboring Bash-Norashen ( Armenian Նորաշեն Norashen , “New -Dorf “, 1964–1991 Ильичёвск Ilyichovsk and today Şərur ) to Azerbaijan. Karabakh was also added to Azerbaijan, while Sangesur ( Sjunik ), which was held by Armenian rebels as the Republic of Mountain Armenia from February to July 1921 , came to Soviet Armenia , so that Nakhchivan became an Azerbaijani exclave. In 1924 it received the status of the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of Nakhchivan . The largely Armenian-populated, mountainous part of Karabakh was granted limited autonomy as the Autonomous Oblast Nagorno-Karabakh . Armenian children in Nagorno-Karabakh were given classes in Armenian, but no Armenian history was taught. In contrast to Baku, there were hardly any mixed marriages between Armenians and Azeris in Nagorno-Karabakh.

After the establishment of Soviet power in Azerbaijan and the establishment of the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic , many Armenians returned to Baku, where Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh and other parts of Azerbaijan also moved. The Baku Armenian quarter Ermenikend (Erm Armennikənd) - originally a village with Armenian oil workers - increased in population. At the beginning of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in 1988, there were more Armenians in Baku than in Nagorno-Karabakh. Quite a few Armenians also worked in state administration. Thus, the number of Armenians in the Azerbaijani SSR reached an all-time high of 475,486 people in the 1979 census, which was 7.9% of the population.

Because of its multiethnic character, a Russian-speaking educated class of the population developed in Baku, especially after the Second World War , in which ethnic origin played an increasingly minor role. Russian became increasingly the first language among the people of Armenian origin in Baku. In 1977, 58% of Armenian students in Azerbaijan attended Russian-language schools . While the Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast remained largely to themselves and there was almost exclusively endogamy , in the urban milieu of Baku there were often ethnically mixed Azerbaijani-Armenian marriages, from which Russian-speaking families emerged. Azeris and Armenians lived largely peacefully as normal neighbors in Baku, and the common Russian language meant that there were no language barriers for the children either, as was the other way around with the Azeris in Yerevan with their Armenian neighbors. Later on, such good neighborly relationships would become lifesaving for many. In 1979, 8% of Armenians in Azerbaijan spoke Azerbaijani, but 43% spoke Russian. Several well-known scientists, artists and athletes emerged from the Armenian-born intelligentsia Bakus, including the Soviet conductor Arshak Adamyan (1884–1956), the Soviet computer technician Boris Artaschessowitsch Babajan (* 1933), the Soviet comedian Yevgeny Vaganovich Petrosian (* 1945) Russian conflict researcher Svetlana Achundowna Tatunz (* 1953), the Uzbek football player and coach Vadim Karlenowitsch Abramow (* 1962), the Russian sword fencer Karina Borissovna Asnavurjan (* 1974), the Russian film director and film producer Anna Melikjan (* 1976) and the Armenian Schachspielerin Elina Danieljan (* 1978). From Jelisawetpol or Kirowabad there were among others the composer Haro Stepanjan (1897-1966) and the wrestler Artyom Sarkissowitsch Terjan (1930-1970).

In the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of Nakhichevan, the proportion and also the absolute number of Armenians fell sharply under Soviet rule, as many Armenians emigrated to the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic over time . While there were still 40% Armenians in Ujezd Nakhichevan in 1916, in 1926 in the ASSR Nakhichevan - albeit with different limits - there were still 11%. In 1979 the proportion of Armenians in the Nakhchivan ASSR was only 1.4%. Conversely, the Azerbaijanis, whose number increased due to immigration from Armenia ( Sjunik ) and a higher birth rate, made up 85% of the population in 1926 and 96% in 1979.

Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

The proportion of Armenians also decreased in Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast. In 1923, 94% of the population was Armenians; in 1989, of around 188,000 people, 73.5% were Armenians and 25.3% were Azerbaijanis. In four memoranda in 1962, 1965, 1967 and finally 1987, the Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh demanded annexation to Armenia. Azerbaijan rejected the demands, saying that Azerbaijanis living in Armenia had no minority rights at all. This was followed by demonstrations, first in Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia, and later in the opposite direction in Azerbaijan. After reports of alleged atrocities against Azeris in Armenia, the pogrom broke out in Sumgait at the end of February 1988 , in which, according to official information, 26 Armenians and six Azeris, but probably up to 200 people, were killed. While the Armenians began to flee Sumgait and other places in Azerbaijan, more and more Azerbaijani refugees and displaced persons from Armenia began arriving in Azerbaijan. In March 1988 the Central Committee of the CPSU rejected an annexation of Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia. As a result, the Soviet of Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast decided to leave Azerbaijan on July 12, 1988. Azerbaijan, with the approval of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, imposed a blockade on Nagorno-Karabakh.

In Kirowabad , the former Yelisavetpol and today's Ganja (Gəncə), which had a very strong Armenian minority of 40,354 people (17.5%) in 1979, over 130 Armenians were killed and over 200 injured in the pogrom in Kirowabad in November 1988 . More Armenians left the city in large numbers, but had to take the route via Georgia due to the closed borders to Armenia . From January 12 to November 29, 1989 Nagorno-Karabakh was under direct administration by the Moscow headquarters. While Azerbaijani protesters demanded Baku control of Nagorno-Karabakh, the Armenians there demonstrated for independence. The Azerbaijan Supreme Soviet declared Nagorno-Karabakh to be part of Azerbaijan by law. A referendum was planned for border changes, but this was announced as early as 1923 and never implemented. In September 1989, 180,000 Armenians had fled Azerbaijan and around 100,000 Azeris had fled Armenia. Those who fled during this period included Anna Astwazaturowa, who would later become the American author at the time, with her parents. For Sumgait as well as for Kirowabad and later for Baku it is reported that it was often Azerbaijani neighbors who hid the Armenians to protect them from persecution and thus enabled them to escape safely - in some cases at the risk of their own lives. The Sumgait pogrom, like the Kirovabad pogrom afterwards, aroused great horror among the non-nationalist layers of the big cities, and the situation in Baku was increasingly felt to be unbearable for the Armenians. In 1988, for example, the Armenians in Baku and Azeris in Yerevan organized the exchange of apartments, as they felt that the time of multicultural coexistence was coming to an end, and self-organized population exchanges took place.

On December 1, 1989, the Supreme Soviet of Armenia declared the unification of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia.

On January 12, 1990, Azerbaijani nationalist forces organized the seven-day pogrom in Baku , which killed around 90 Armenians. The people on whom lists had been prepared before the attacks were mainly murdered by blows and knife wounds; houses were also set on fire. The only Armenian church still in use in Baku towards the end of the Soviet era, the Church of Saint Gregory the Illuminator , burned down while the fire brigade and police watched. The invasion of the Soviet Army on the night of January 19-20, 1990, referred to by the Azerbaijanis as " Black January ", put an end to the pogrom, but 93 Azerbaijanis and 29 Soviet soldiers were killed in the crackdown on the nationalist riots. As a result, most of the Armenians, but also some of the Russians, fled Baku, including the former world chess champion Garry Kasparov and his family. While the proportion of Armenians in Baku, according to the 1979 census, was 16.5% - 215,000 people - the number was estimated at around 18,000 at the end of April 1993 and in 2009 was practically 0%.

While Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh began to form armed militias for self-defense, Azerbaijani OMON forces and units of the Soviet Army carried out " Operation Ring " (Операция "Кольцо") from April 30 to May 15, 1991 , according to Human Rights Watch launched a campaign to depopulate the centuries-old Armenian-populated villages north and south of Nagorno-Karabakh Oblast, as well as in the Oblast itself. The operation was officially referred to as "passport control", but internally the aim was to disarm illegally armed Armenian formations. To the north of the Autonomous Oblast was the almost entirely Armenian-populated Rajon Shaumyan with the capital Shaumyanovsk ( Russian Шаумя́новск ) or Shahumyan ( Armenian Շահումյան ), which until 1938 was Nerkin Schen (Неркин Шен or Ներքին Շեն, "lower" or "inner hamlet") and was then named after Stepan Shaumyan . Military units surrounded the villages with tanks and took them under fire. Armenian leaders Tatul Krpejan and Simon Achikgjosjan , among others, died in the operations . About 17,000 Armenians from Shahumyan Raion were forced to leave the country. The completely depopulated villages included Martunas and Beaschen (Çaykənd).

After Nagorno-Karabakh declared its independence on September 2, 1991 (shortly after Armenia and Azerbaijan declared independence), 99.9% voted in a referendum on independence on December 10, 1991 with a turnout of 82.2%. In December 1991, the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic also declared Shaumyan Raion to be an integral part of Nagorno-Karabakh. The Shoamyanovsk area became the first battlefield in the Nagorno-Karabakh war. In the summer of 1992, the Azerbaijani army gained final control over the area that was now Armenian-free. Shaumyanovsk, the former Nerkin Shen, was given the new Azerbaijani name Aşağı Ağcakənd in 1992 and was partially repopulated with Azerbaijanis - refugees from Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh - in the following months .

Pogroms against Armenians also occurred in the cities of Xanlar and Lənkəran . According to Human Rights Watch , an estimated 350,000 Armenians fled in two waves in 1988 and 1990 after the anti-Armenian violence. By 1991 a total of 500,000 people had already left Azerbaijan.

The Armenian combat units set up in Nagorno-Karabakh, with the support of the Armenian armed forces and the Armenian diaspora, succeeded in capturing the greater part of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast and neighboring areas - especially towards Armenia - until the conclusion of an armistice in 1994. Just like Shaumyanovsk, however, the Karabakh Armenians also had to give up two areas in the east of the Autonomous Oblast. Maraga (Մարաղա, Maragha or Marağa ) and Leninawan (Լենինավան, formerly Marguschewan, Մարգուշեվան) were located on the eastern edge of Martakert Province and were stormed by Azerbaijani troops on April 10, 1992, after most of the residents had been able to flee. However, over 100 people remained, the majority of them physically handicapped and the elderly. According to a report by Baroness Caroline Cox , around 45 villagers were beheaded by Azerbaijani soldiers and others burned during the Maraga massacre . Around 100 women and children were also kidnapped as hostages. The killing of the Maragha villagers was also seen as retaliation for the more than 160 Azerbaijani victims in Chodjali who were killed by Karabakh-Armenian troops on February 25, 1992 while they were taking the important Azerbaijani base. However, the Armenian side argued that the Maragha massacre was carried out to eliminate the local Armenian population and to secure the oil reserves there for Azerbaijan. Maragha remained a desert afterwards , but it was given a new Azerbaijani name: Şıxarx (previously Marağa). The refugees established the village of Nor Maragha within the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (but outside the former Autonomous Oblast) , where they also erected a memorial to those who died in the massacre. Other Armenian refugees ended up in Russia or Armenia. The refugees stranded in Russia often lack the money to return to Nagorno-Karabakh (the areas controlled by the Artsakh Republic ).

Current status in the Republic of Azerbaijan

As a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh War, around 12,000 square kilometers or 13.62% of the area of the former Azerbaijani Soviet Republic are currently under the control of the Artsakh Republic . According to the census, 146,600 people lived here in 2012, almost exclusively Armenians. Most of them are former residents of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast and their descendants, but also some Armenian refugees from the other areas of the former Azerbaijani SSR. The reality of their life is completely different from that of those Armenians who remained under Azerbaijani rule.

According to unofficial estimates, the number of Armenians in the territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan in 1999 was around 2,000 to 3,000 people, the majority of whom were married to people of Azerbaijani ethnic identity or of mixed origin. The estimated 36 Armenian men and 609 Armenian women - more than half of whom live in Baku - who did not do this, were mostly old or sick. The situation of the Armenians in Azerbaijan is very precarious, which is why most of them try to hide their Armenian identity. Of the once numerous Armenian churches, none are in use anymore.

In Baku, which once had over 200,000 Armenians, 104 people out of a good 2 million inhabitants stated in the 2009 census to be Armenians. In no other Rajon outside Nagorno-Karabakh did the number of Armenians reach 10 people.

In Azerbaijan, hostility towards Armenians is ubiquitous on an institutional and social level, so according to the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, Armenians in Azerbaijan are the most vulnerable group to racism and racial discrimination. President İlham Əliyev spread his anti-Armenian propaganda very openly and bluntly shortly before the start of the Eurovision Song Contest 2012 , when he declared “all Armenians worldwide” to be the number one public enemy. Under these conditions, it is impossible for Armenians who have remained under the control of the Republic of Azerbaijan to reveal their Armenian identity to the outside world.

Cultural heritage

Material evidence of the former Armenian presence in today's Azerbaijan are in particular the church buildings and cemeteries of the Armenian Apostolic Church with their khachkars and Armenian inscriptions. These are described in detail for the Nakhichevan ASSR by the Nakhichevan-Armenian historian and journalist Argam Aivazian (Արգամ Այվազյան, * 1947 in Airink ), who now lives in Yerevan, in his " Nakhchivan : Book of Monuments", photos from the years 1965 to 1987 contains. In 2005, the American orientalist Steven Sim undertook a trip through Nakhchivan, during which he was guided by the information in Aivazian's monument guide. However, he did not find any more Armenian churches, rather he saw traces of stones and bricks from recently demolished buildings in the specified places. All interviewees said that there were never any Armenians in Nakhichevan. Eventually Sim was arrested and expelled from the country.

In 1920 there were three Armenian churches in Baku. The St. Thaddäus and Bartholomäus Cathedral , built from 1906 to 1907, was destroyed as part of the anti-church policies under Stalin in the 1930s to make way for the Baku Music Academy . The 18th century Church of Our Lady on the Maiden's Tower in Baku's old town was no longer used from 1984 and demolished in 1992. The Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator was set on fire in the Baku pogrom in 1990 and renovated in 2004 to serve as the archive building for the Administrative Affairs Department of the Presidential Administration of Azerbaijan. |

Today there is no longer an Armenian church in Azerbaijan that is used as such. There have been various reports of the targeted destruction of the Armenian cultural heritage in Azerbaijan. The deliberate final destruction of the Armenian cemetery in Jugha by Azerbaijani soldiers in December 2005 and the subsequent establishment of a firing range on the leveled area attracted international attention , which was to the annoyance of the Azerbaijani leadership by Armenian clergymen , including Tabriz Bishop Nshan Topouzian , from the Iranian bank was filmed over the Arax. Both Nakhichevan's representative in Baku, Hasan Zejnalow , and President Ilham Aliyev described the documented destruction as a "lie". In an interview with the BBC in December 2005, Zejnalov said that Armenians had never lived in Nakhchivan, which has been an Azerbaijani country for a long time, and that is why there have never been any Armenian monuments there in history. In the official Azerbaijani historiography it is claimed that the Khachkars in Azerbaijan are not of Armenian, but of " Albanian " origin and that the "Albanians" are direct ancestors of the Azerbaijanis.

Artistic processing in Azerbaijan and political reactions

The popular Azerbaijani writer Akram Aylisli published the novel "Dreams of Stone" in December 2012, in which he addresses the pogroms in Sumgait and Baku as well as the massacres of Armenians in his Nakhchivan hometown by Turkish troops in 1918 and the exodus of the Armenians from Nakhchivan . Although he had already written the text in 2006, he has so far shied away from publication. After the convicted and confessed murderer Ramil Səfərov , who had beheaded a sleeping Armenian officer with an ax in Hungary, was received as a national hero in Baku, he did publish the novel. "When I saw this insane reaction and how they artificially fueled the hatred between Armenians and Azerbaijani in a way that went beyond any scope, I decided to publish the novel." The state reward for this, however, was to him by order of President İlham Əliyev to withdraw all awards and the pension and to delete his works from the repertoire of theaters and the curriculum of schools.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Первая Всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Под ред. Н.A.Tройницкого. т.II. Общий свод по Империи результатов разработки данных Первой Всеобщей переписи населении населения, населения населения, произведяния, произвед 18 .97. С.-Петербург, 1905. Таблица XIII. Распределение населения по родному языку, в: Первая всеобщая перепись населения Росисийской Импер.1897 Импер. Распределение населения по родному языку, губерниям и областям. В расположенном ниже списке выберите регион. Эриванская губерния. Демоскоп (Demoscope.ru), 2017.

- ^ Robert Hewsen : Armenia: A Historical Atlas . Chicago University Press, Chicago 2001.

- ^ E. Yarshater: The Iranian Language of Azerbaijan. Encyclopædia Iranica, August 18, 2011.

- ^ CE Bosworth: Arran. Encyclopædia Iranica, August 12, 2011.

- ↑ Olivier Roy: The new Central Asia. IB Tauris, London 2007. ISBN 978-1-84511-552-4 , p. 6 .

- ^ A b c George A. Bournoutian: The Population of Persian Armenia Prior to and Immediately Following its Annexation to the Russian Empire: 1826-1832 . The Wilson Center, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies, Washington 1980. pp. 11-14.

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen: The Kingdom of Arc'ax , in: Thomas J. Samuelian and Michael E. Stone (eds.): Medieval Armenian Culture . University of Pennsylvania Armenian Texts and Studies, Scholars Press, Chico (California) 1984. pp. 52-53. ISBN 0-89130-642-0

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen: The Meliks of Eastern Armenia: A Preliminary Study. Revue des Études Arméniennes 9 (1972). Pp. 299-301.

- ↑ H. Nahavandi, Y. Bomati: Shah Abbas, empereur de Perse (1587-1629). Perrin, Paris 1998.

- ↑ Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi (author), George A. Bournoutian (translator): A History of Qarabagh: An Annotated Translation of Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi's Tarikh-E Qarabagh. Mazda Publishers, Costa Mesa 1994. p. 18.

- ↑ Jos JS Weitenberg: Armenia. In: Ulrich Ammon (Ed.): Sociolinguistics: An International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society , Volume 3. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2006. pp. 1900–1902, here 1901.

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Black Garden - Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8147-1944-9 , p. 151.

- ↑ Бакур Карапетян, Самвел Карапетян [Bakur Karapetjan, Samwel Karapetjan]: Тайны Гандзака (Кировабада) и Северного. Детская книга, Москва [Moscow] 1998.

- ↑ Александр Саркисович Манасян [Alexander Zarkissowitsch Manasjan]: Карабахский конфликт в ключевых понятиях и имфрансаныz и имфранский конфликт в ключевых понятиях и имфрансаныz и имфрансаныz. Ереван [Yerevan], 2002. p. 45.

- ↑ А. Т. Марутян, Г. Г. Саркисян, З. В. Харатян [HT Maroutian, HG Sargsian, ZV Kharatian]: К этнокультурной характеристике Арцаха. [On the ethno-cultural characteristics of Arzach]. Լրաբեր հասարակական գիտությունների 6, pp. 3–18. Հայաստանի գիտությունների ակադեմիա [Armenian Academy of Sciences], Ереван [Yerevan] 1989. ISSN 0320-8117

- ↑ Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897

- ^ Brockhaus Konversations-Lexikon, 14th edition. Volume 14, entry Schuschá. Leipzig, Berlin, Vienna 1895.

- ^ A b Richard G. Hovannisian: Republic of Armenia: The first year, 1918-1919 (Vol. I). University of California Press, Berkeley 1971. p. 91. ISBN 0-520-01984-9

- ^ Svante Cornell: Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus, Taylor & Francis, London 2000. p. 69.

- ^ Tadeusz Swietochowski: Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. Columbia University Press, New York City 1995. ISBN 0-231-07068-3 , ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3

- ↑ Richard G. Hovannisian: Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918. University of California Press, Berkeley 1967, pp. 15-16. ISBN 0-520-00574-0

- ^ Peter Hopkirk: Like Hidden Fire. The Plot to Bring Down the British Empire . Kodansha Globe, New York 1994, p. 287. ISBN 1-56836-127-0

- ↑ Michael Smith: Anatomy of Rumor: Murder Scandal, the Musavat Party and Narrative of the Russian Revolution in Baku, 1917-1920 . Journal of Contemporary History 36 (2), April 2001, p. 228. doi: 10.1177 / 002200940103600202 .

- ↑ a b Michael Croissant: The Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict: causes and implications. Greenwood Publishing Group, Westport (Connecticut) 1998. p. 14. ISBN 0-275-96241-5 .

- ↑ Decree of President of Republic of Azerbaijan about genocide of Azerbaijani people. Heydar Aliyev, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Baku, March 26, 1998.

- ^ Richard G. Hovannisian: Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918. University of California Press, Berkeley 1967, pp. 225-227, 312, note 36. ISBN 0-520-00574-0

- ^ Tadeusz Swietochowski: Russian Azerbaijan, 1905-1920: The Shaping of National Identity in a Muslim Community . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1985, p. 145.

- ^ John FR Wright: Transcaucasian Boundaries . Psychology Press, 1996, pp. 99 ( online ).

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Black Garden - Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8147-1944-9

- ↑ a b Richard G. Hovannisian. The Republic of Armenia, Vol. III: From London to Sèvres, February – August 1920

- ↑ a b Lords Hansard, text for July 1, 1997 (170701-19)

- ↑ Игорь Бабанов, Константин Воеводский: Карабахский кризис, Санкт-Петербург, 1992

- ↑ World Directory of Minorities , p. 145 ( Minority Rights Group , Miranda Bruce-Mitford)

- ↑ Kalli Raptis, Nagorno-Karabakh and the Eurasian Transport Corridor

- ↑ Commission de Refugies, France ( PDF )

- ↑ Tobias Debiel, Axel Klein: Fragile Peace: State Failure, Violence and Development in Crisis Regions. Zed Books, London 2002, p. 94.

- ↑ TKOommen: Citizenship, nationality, and ethnicity. Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken (New Jersey) 1997. p. 131.

- ↑ Алла Ервандовна Тер-Саркисянц [Alla Erwandovna Ter-Sarkisjants]: Современная семья у армян Нагорного Карабаха [The modern Bergkarabach family]. In: В.К. Гарданов [VK Gardanov] (ed.). Кавказский этнографический сборник Kavkazskij ètnografičeskij sbornik , 6: 11-46; P. 34.

- ↑ Николай Николаевич Баранский [Nikolai Nikolajewitsch Baransky ]: Экономическая география СССР [Economic Geography of the USSR]. Государственное учебно-педагогическое издательство Наркомпроса РСФСР [State Educational and Educational Publishing House], Москва [Moscow] 1938, p. 305.

- ^ Anoushiravan Ehteshami: From the Gulf to Central Asia . University of Exeter Press, Exeter 1994, p. 164.

- ^ Encyclopedia Americana. Azerbaijan, Republic of . Grolier Incorporated, 1993.

- ↑ РГАЭ РФ (быв. ЦГАНХ СССР), фонд 1562, опись 336, ед.хр. 6174-6238 (Таблица 9с. Распределение населения по национальности и родному языку), в: Всесоьгная Всесоьзная перепа 1979. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР: Азербайджанская ССР. Демоскоп (Demoscope.ru), 2017.

- ↑ Сергей Румянцев [Sergei Rumyantsev]: Столица, город или деревня. Об итогах урбанизации в отдельно взятой республике на Южном Кавказе . Демоскоп [Demoscope Weekly]. 10-23. October 2005.

- ↑ Мераб Константинович Мамардашвили [Merab Konstantinovich Mamardashvili]: " « Солнечное сплетение »Евразии ."

- ↑ Иван Костянтыновыч Билодид [Ivan Kostyantynovich Bilodid]: Русский язык как средство межнационального общения as a means between the Russian language. Наука, Москва [Nauka, Moscow] 1977, p. 164.

- ↑ Vladimir Shlapentokh: A Normal Totalitarian Society: How the Soviet Union Functioned and How It Collapsed . ME Sharpe, Armonk (New York) 2001, p. 269.

- ↑ a b Günel Mövlud, Aziz Kerimov, Gayane Mkrtchian: Karabakh and the Ban on Memory. Meydan TV, December 15, 2016.

- ↑ Audrey Altstadt: The Azerbaijani Turks: Power and Identity Under Russian Rule. Hoover Press, 1992. p. 187.

- ^ Nakhchivan ASSR in the 1926 All-Soviet Census

- ↑ Население Азербайджана

- ↑ a b Eva-Maria Auch : Nagorno Karabakh - War for the «black garden» in the Caucasus - history-culture-politics . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2010 (2nd edition).

- ↑ Arie Vaserman, Ram Ginat (1994): National, territorial or religious conflict? The case of Nagorno-Karabakh. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 17 (4), p. 348. doi: 10.1080 / 10576109408435961 .

- ↑ a b Eva-Maria Also: "Eternal Fire" in Azerbaijan - A country between perestroika, civil war and independence. Reports of the Federal Institute for Eastern and International Studies, No. 8, 1992.

- ↑ Anna Astvatsaturian-Turcotte: 100 Lives. Auroraprize.com, December 12, 2015.

- ↑ Новый Мир, 7–9. Известия Совета Депутатов Трудящихся СССР, 1998, p. 189.

- ^ Huberta von Voss: Portraits of Hope: Armenians in the Contemporary World. Berghahn Books, New York 2007, p. 301.

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Black Garden - Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8147-1944-9 , p. 90.

- ↑ Robert Kushen: Conflict in the Soviet Union: Black January in Azerbaidzhan, 1991, Human Rights Watch , p.7

- ↑ 1990: Gorbachev explains crackdown in Azerbaijan. BBC , January 22, 1990. Retrieved October 24, 2012

- ^ Bill Keller: Upheaval in the East: Soviet Union. A Once-Docile Azerbaijani City Bridles Under the Kremlin's Grip. The New York Times , February 18, 1990.

- ↑ Kasparov Chess Foundation: Garry Kasparov - Bio ( Memento from March 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ State Statistical Committee of the Azerbaijan Republic, Ethnic composition of Azerbaijan 2009

- ^ HRW Report on Soviet Union Human Rights Developments [in 1991]. Human Rights Watch , 1992.

- ^ Azerbaijan: Seven years of conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh. Human Rights Watch, New York 1994, p. 9.

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York University Press, New York 2003, p. 114. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7 .

- ↑ М. Гохман [M. Gokhman]: "Карабахская война," [The Karabakh War] Русская мысль [Russkaja Misl], November 29, 1991.

- ^ Mark Elliott: "Azerbaijan with Excursions to Georgia", Trailblazer, Hindhead (UK) 2004, p. 245.

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York University Press, New York 2003, p. 116. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7 .

- ↑ Референдум - MFA NKR. In: www.nkr.am. Archived from the original on March 14, 2015 (Russian).

- ^ Report on the Results of the Referendum on the Independence of the Nagorno Karabakh Republic. In: nkr.am. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013 .

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York University Press, New York 2003, pp. 116, 194f. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7 .

- ↑ Azerbaijan with Excursions to Georgia , Trailblazer, Hindhead (UK) 2004, p. 245.

- ^ Human Rights Watch : Azerbaijan: seven years of conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh . Humans Rights Watch, New York 1994, ISBN 1-56432-142-8 .

- ↑ Survivors of the Maraghar Massacre . Christianity Today . April 27, 1998. Retrieved January 11, 2013

- ^ Caroline Cox, John Eibner: Ethnic Cleansing in Progress: War in Nagorno Karabakh. Institute for Religious Minorities in the Islamic World, p. 58, 1993

- ^ Oil factor had role in Maragha tragedy, Armenian MP says . Panarmenian.net, accessed January 11, 2013.

- ↑ Caroline Cox: Survivors of the Maraghar Massacre. Christianity Today, April 27, 1998.

- ↑ Amnesty International: Azerbaijan - Hostages of the Karabakh conflict: Civilians still have to suffer. April 1993

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Armenia / Azerbaijan: Myths and realities of Karabakh war. Institute for War and Peace Reporting, May 1, 2003.

- ↑ Nagorno-Karabakh Census , January 1, 2013 (PDF).

- ↑ Этнический состав Азербайджана (по переписи 1999 года) Этнический состав Азербайджана (по переписи 1999 года) ( Memento of 21 August 2013, Internet Archive )

- ^ Definitions of national identity, nationalism and ethnicity in post-Soviet Azerbaijan in the 1990s

- ↑ European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), Second Report on Azerbaijan, CRI (2007) 22, May 24, 2007

- ^ A b University of Maryland Center for International Development and Conflict Management. Minorities at Risk: Assessment of Armenians in Azerbaijan. Online Report, 2004.

- ↑ Razmik Panossian. The Armenians. Columbia University Press, 2006; p. 281

- ^ Mario Apostolov. The Christian-Muslim Frontier. Routledge, 2004; p. 67

- ^ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. 2001

- ↑ Barbara Larkin. International Religious Freedom (2000): Report to Congress by the Department of State. DIANE Publishing, 2001; p. 256

- ↑ Azerbaijan: The status of Armenians, Russians, Jews and other minorities, report, 1993, INS Resource Information Center, p. 10

- ^ United States Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 1992 (Washington: US Government Printing Office, February 1993), p. 708.

- ↑ Tim Bespyatov: Ethnic composition of Azerbaijan 2009. (Census of Azerbaijan, 2009.)

- ↑ Editor Fyodor Lukyanov : Первый и неразрешимый. In: Russia in Global Affairs. Wsgljad , August 2, 2011, archived from the original on November 23, 2011 ; Retrieved January 12, 2013 (Russian): "Армянофобия - институциональная часть современной азербайджанской госвайджанской госвекой госудкенгнгевенености. "Hostility towards Armenians is an institutional part of today's Azerbaijani statehood, and ultimately Karabakh is at the center of everything."

- ^ Second report on Azerbaijan. (PDF; 425 kB) European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, Strasbourg, May 24, 2007, archived from the original on September 21, 2013 (English).

- ^ Report on Azerbaijan. (PDF; 417 kB) European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, Strasbourg, April 15, 2013, p. 2 , archived from the original on September 21, 2013 (English): “Due to the conflict, there is a widespread negative sentiment toward Armenians in Azerbaijani society today. "" In general, hate-speech and derogatory public statements against Armenians take place routinely. "

- ^ Armenia pulls out of Azerbaijan-hosted Eurovision show . BBC . Retrieved August 7, 2013

- ^ Border soldier killed: Armenia boycotted the Eurovision Song Contest . The mirror . Retrieved August 8, 2013

- ↑ Արգամ Արարատի Այվազյան (Аргам Араратович Айвазян / Argam Araratovich Aivazian): Նախիջեւան. գիրք հուշարձանաց / Nakhijevan: Book of Monuments . Երևան (Yerevan), 1990. OCLC 26842386 - Engl. The Historical Monuments of Nakhichevan. Translated into English by Krikor H. Maksoudian. Wayne State University Press, Detroit 1990.

- ↑ Steven Sim: Nakhichevan 2005: The State of Armenian Monuments. January 2006.

- ↑ Армянский Собор во имя Св. апостолов Фаддея и Варфоломея - Будаговский собор (Баку). Наш Баку - История Баку и бакинцев, October 20, 2017.

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Black Garden - Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8147-1944-9 , p. 103.

- ↑ Implementation of the Helsinki Accords: "Human Rights and Democratization in the Newly Independent States of the former Soviet Union" . Washington, DC: US Congress, Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, January 1993, p. 116.

- ↑ Günay Musayeva: Prezident Kitabxanasının balansında olan məbəddə hələ də təmir gedir; müvafiq qurumlar isə “bu kilsə bərpa olunmayacaq” deyir ... Yeni Müsavat, August 5, 2011, archived from the original on April 6, 2012 (Azerbaijani).

- ↑ Azerbaijan: The Status of Armenians, Russians, Jews and other minorities. (PDF; 96 kB) Immigration and Naturalization Service ; Washington, DC, 1993, p. 10 , accessed January 25, 2013 : “Despite the constitutional guarantees against religious discrimination, numerous acts of vandalism against the Armenian Apostolic Church have been reported throughout Azerbaijan. These acts are clearly connected to anti-Armenian sentiments brought to the surface by the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan. "

- ↑ Stephen Castle: Azerbaijan 'flattened' sacred Armenian site. The Independent , April 16, 2006.

- ^ A b Sarah Pickman: Tragedy on the Araxes. Archeology , June 30, 2006.

- ^ Thomas De Waal: The Caucasus: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2010, pp. 107-108.

- ↑ Виктор Александрович Шнирельман: Войны памяти. Мифы, идентичность и политика в Закавказье . , М., ИКЦ, "Академкнига", 2003.

- ↑ Yo'av Karny, Highlanders: A Journey to the Caucasus in Quest of Memory. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York 2001. p. 376, chapter Ghosts of Caucasian Albania.

- ↑ Thomas de Waal: Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. 2004, pp. 152-153, 143.

- ^ Svante Cornell: Small nations and great powers. Routledge 2000, p. 50.

- ^ Philip L. Kohl, Clare P. Fawcett: Nationalism, politics, and the practice of archeology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1996, pp. 152-153.

- ↑ Ben Fowkes: Ethnicity and ethnic conflict in the post-communist world. Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, p. 30.

- ↑ Baku myths about 'Albanian crosses'. Panarmenian.NET, November 25, 2012.

- ↑ Акрам АЙЛИСЛИ: Каменные сны. Дружба Народов 2012, 12 ( online at Журнальный зал )

- ^ Ernst von Waldenfels: writer Akram Aylisli: ax and pen. How the Azerbaijani writer went from a living classic to an enemy of the people.

- ↑ Azerbaijani President signs orders to deprive Akram Aylisli of presidential pension and honorary title , Trend.az.

- ↑ Распоряжение Президента Азербайджанской Республики о лишении Акрама Айлисли (Акрама Наджаф оглу Наибова) персональной пенсии Президента Азербайджанской Республики

- ↑ В Азербайджане изымают из школьных учебников произведения опального писателя: Подробнее