Aśoka edicts

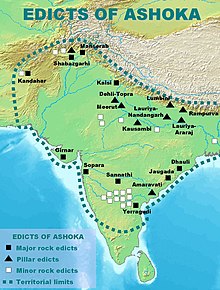

As Aśoka edicts or Ashoka edicts (pronounced Aschoka edicts ) are 33 texts that were written in the 3rd century BC. Under the reign of the emperor Ashoka (ruled approx. 268–232 BC) as inscriptions on free-standing columns, on rocks and on the walls of caves, were spread throughout his empire. Ashoka from the Maurya dynasty, who had founded the oldest Indian empire and had converted to Buddhism , had the main features of his later politics recorded, which were based on the teachings of the Buddha , the Dharma .

The lions, a symbol of rule and at that time also a symbol of Siddhartha Gautama , who was born as a prince and who lived around 250 BC The Ashoka pillar built in Sarnath in the 3rd century BC are now the coat of arms of the state of India . In addition to lions, a number of Ashoka pillars also carried the “wheel of Dharma” ( dharmachakra ) on top.

Subdivision

The edicts received from each group are the same or similar; They are usually subdivided as follows, with the smaller rock and pillar edicts dating a few years or decades older than the larger:

- 14 major rock edicts

- 17 (?) Minor rock edicts

- 7 major pillar edicts

- 5 smaller pillar edicts

- 2 separate dictates

- 2 donation edicts in caves

Languages and scripts

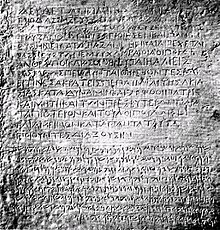

The edicts were written in the various languages and scripts of the peoples of the empire and were intended to proclaim the "rule of the Dharma" in his entire territory, which included the entire northern part of the Indian subcontinent including large parts of present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan . In the east and central region of northern India, the edicts were written in the Magadhi language and written in Brahmi script . Further to the northwest (see also Gandhara ), edicts in Kharoshthi script in Greek and Aramaic were also found. The Saken wrote a 400 years later Sanskrit inscription on one of the edicts, which is also the first written testimony of Sanskrit.

Overview of the content

The inscriptions expressed the king's will to make Buddhist teachings known throughout the empire as the basis of his rule. The Buddha and the Dharma were mentioned repeatedly in the edicts, but they mostly concentrate more on moral and ethical statements than on religious practice. The philosophical dimensions of Buddhism, namely the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path , are not to be found in the texts. Whether this happened because he wanted to keep the texts generally understandable for the broad mass of the population, or because these contents were formalized later - or both - has not yet been finally clarified. The content of the edicts repeats a number of central themes:

- the king's conversion to Buddhism

- Descriptions of his efforts to spread the Dharma

- the king's moral and religious beliefs based on the Dharma

- his efforts to implement these convictions in the form of a social and peaceful policy.

Ashoka himself is referred to as Piyadasi in the inscriptions .

King Ashoka's conversion to Buddhism

At the beginning of his reign, Ashoka was a successful general who expanded his empire through military campaigns, consolidated his rule and founded the first great Indian empire. After a particularly bloody and costly battle in which he defeated the army of Kalinga in what is now the state of Orissa , he finally ended his campaigns and turned to Buddhism. These events are narrated in a rock edict:

“King Piyadasi conquered the Kalingas eight years after his coronation. One hundred and fifty thousand were displaced, one hundred thousand killed, and many more died (for other reasons). After the Kalingas were conquered, Piyadasi felt a strong devotion to the Dharma, a love of the Dharma and the teaching of the Dharma. Now Piyadasi feels great regret for having defeated the Kalingas. "

After becoming a follower of the Buddha's teachings, Ashoka traveled through the country and visited several places of importance to Buddhism such as Lumbini , the birthplace of Siddhartha Gautamas , Bodhgaya , the place where he learned Bodhi ("enlightenment", "awakening") ) and became a Buddha, or Isipatana (near today's Sarnath ), where the first discourse of the Awakened One took place. At all these places he had stone pillars erected with edicts inscribed on them. An edict on the Ashoka Pillar in Sarnath reads:

“Twenty years after his coronation, King Piyadasi visited this place and showed his devotion because it was here that the Buddha, Shakymuni ['the sage of the Shakya clan'], was born. He had a stone figure and a column erected and, because the Buddha was born here, exempted the town of Lumbini from taxes and demanded payment of only one eighth of the proceeds. "

Spreading the teachings of the Buddha

In order to spread Buddhism, Ashoka sent his envoys to all of India and also to the Hellenistic empires on the Mediterranean ( Graeco Buddhism ). He claimed to have led them all to Buddhism.

Spread outside of Ashoka's realm

In particular, a number of kings are mentioned in edicts who ruled Hellenistic empires such as Bactria in northwest India, Greece and Egypt as a result of the campaigns of Alexander the Great . The corresponding texts testify to a very clear understanding of the power relations in these regions at that time.

“Now it is conquest by the Dharma that the Piyadasi consider the best conquest. And this was achieved here, on the borders, even six hundred Yojanas away, where the Greek king Antiochus rules, beyond where the four kings with the names Ptolemaios , Antigonus , Magas and Alexander rule, also in the south under the Cholas , the Pandyas and so on far away like Tamraparni . "

The distance of 600 yojanas (1 yojana = approx. 11 km) corresponds roughly to the distance from India to Greece.

- Antiochus refers to Antiochus II (261-246 BC), ruler of the Seleucid Empire (from today's Syria to Bactria ) and thus a direct neighbor of the India of the Maurya dynasty

- Ptolemy is Ptolemy II of Egypt (285-247 BC), an heir of the Ptolemy ruling dynasty founded by Ptolemy I (a general of Alexander the Great)

- Antigonus is Antigonus II Gonatas of Macedon (278-239 BC)

- Magas is Magas of Cyrene (300-258 BC)

- Alexander is Alexander II of Epirus (272-258 BC)

- The Cholas and Pandyas were rulers in the south of the Indian subcontinent, outside of Ashoka's empire.

- Tamraparni was an earlier name of the island of Sri Lanka .

It has not yet been possible to establish with certainty whether the emissaries of Ashoka were actually received and listened to by the kings of the Hellenistic empires or whether they had a demonstrable influence on these cultures. In individual cases, however, evidence can be found: for example, the Greek theologian Clemens of Alexandria (approx. 150–215) reports of a Buddhist community in Alexandria ( Sanskrit ḷ āḷasaḍā “A'lasada”). Also in Alexandria were found Buddhist tombstones from the time of the Ptolemies, which were decorated with depictions of the "Wheel of Dharma" ( Dharmachakra ).

Spread in Ashoka's realm

The kingdom of King Ashoka extended over the territories of a multitude of different peoples; This becomes clear, for example, in the following edict:

"Here in the kingdom of the king among the Greeks, the Kamboja, the Nabhaka, the Nabhapamkit, the Bhoja, the Pitinika, the Andhra and the Palida, everywhere people follow the teachings of Piyadasi in the Dharma."

“Greeks” lived in the northwest of the Maurya Empire, especially in the country of Gandhara (today eastern Afghanistan and western Pakistan). Their ancestors had come to the region with the armies of Alexander the Great, who in 326 BC. The capital Taxila had taken. An edict of the Greeks says:

“It is not a country, except among the Greeks, where these two groups, the Brahmanas and the ascetics, are not known. And it is not a country where people do not belong to one religion or the other. "

Kamboja denotes a people of Central Asian origin who first settled in Arachosia and Drangiana (today southern Afghanistan) and also lived in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, in Sindhu , Gujarat and Sauvira . The Kamboja later also settled areas in Southeast Asia and there is a possibility that they are identical to the Mon , one of the earliest peoples to settle in Thailand and Myanmar .

Nabhaka , Nabhapamkit , Bhoja , Pitinika , Andhra and Palida were other peoples in King Ashoka's kingdom.

Dissemination of moral and ethical principles

The Dharma was spread in the edicts of Ashoka mainly in the form of moral guidelines, which mostly related to meritorious action, respect for all living beings (humans and animals), generosity and purity.

Right action

“Dharma is good, but what is Dharma made of? (It includes) little bad, much good, kindness, generosity, honesty and purity. "

"And noble deeds and the practice of Dharma consist of kindness, generosity, honesty, purity, mildness and the promotion of the good among people."

Charity

“Right action” in the sense of Dharma, as Ashoka had it spread in the edicts, also includes respect for other people and life. In addition, Ashoka also calls for tolerance towards followers of other religions, such as the Hindu brahmanas and ascetics.

"Respect for mother and father is good, generosity towards friends, allies, relatives, brahmanas and ascetics is good, not killing living beings is good, moderation in spending and moderation in keeping are good."

In a rock edict it says:

“This includes appropriate behavior towards servants and servants, respect for teachers, restraint towards living beings, and generosity towards ascetics and brahmanas. These and other things make up the practice of Dharma. "

Kindness to prisoners

Ashoka attached great importance to fair justice, caution and tolerance in reaching a judgment and choosing the punishment. He also repeatedly issued pardons.

“It is my aim that laws and punishments should be uniform. I also go so far as to allow those sentenced to death to stay in prison for three days. During this time, their relatives can apply for a pardon. If no one is there to ask for the life of the prisoner, the prisoner can make gifts to collect good merits for the next world or fast. "

"In the twenty-six years since my coronation, prisoners have received amnesties on twenty-five occasions."

Respect for all living beings

Although Ashoka did not condemn the killing of animals in principle, he forbade animal sacrifices for religious purposes, urged people to exercise moderation so that fewer animals had to be killed for consumption, placed some under his special protection and condemned violence against animals, such as castration .

"May here (in my kingdom) no living being killed or sacrifice to be offered."

“Twenty-six years after my coronation, some animals are placed under protection - parrots, wild geese and ducks, bats, queen ants, turtles, fish, porcupines, squirrels, deer, cattle, wild and domestic pigeons, all quadruped animals that are neither useful nor are edible. The goats, sheep and sows that have young or give milk to young are protected, as are the young when they are younger than six months. Roosters must not be castrated, undergrowth in which animals hide, must not be burned and forests must not be burned down for no reason or to kill living beings. One animal may not be fed to another. "

Religious content

In addition to the dissemination of moral edicts based on Buddhist teachings, Ashoka also made it important that the teachings of the Buddha are read and followed - especially within the monk and nun communities (see also Sangha ):

“Piyadasi, King of Magadha, greets the Sangha and wishes them health and happiness and says: You know, dear ones, how great my faith is in the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. Whatever, venerable, the Buddha spoke, everything is rightly spoken. "

"These texts of the Dharma - excerpts from the rules of discipline, about the right path of life and the fear of the coming, the poem about the silent wise man, the discourse about the pure life, the questions of Upatisa and the teaching of the Buddha to ( his son) Rahula on false speech - these Dharma texts, dear ones, I wish to be read and remembered by all monks and nuns. Likewise from the layperson. "

Cycle of rebirths

"One wins in this world and one achieves great merit for the next one by transmitting the gift of Dharma."

"Happiness in this world and the next is difficult to attain without surrender to the Dharma, a lot of self-reflection, a lot of respect, a lot of fear (of evil) and great enthusiasm."

Religious tolerance

Ashoka did not see the Dharma as the only salvific teaching. Rather, he promoted exchanges between religions, believing that they were essentially based on the same common essence.

"All religions should be spread everywhere, because they all strive for self-control and purity of heart."

“Contacts [between religions] are good. One should listen to and respect the principles of others. King Piyadasi wishes that everyone should be well trained in the principles of other religions. "

Social measures

King Ashoka promoted measures to improve the lives of people (and animals) in and outside of his kingdom. This included, above all, the establishment of hospitals (which were also supposed to accept animals), the construction and improvement of roads and the sending out of “messengers of the Dharma” throughout his empire to guide and monitor these measures and to make the Dharma known.

Healthcare

“Everywhere in the kingdom of King Piyadasi, and with the peoples beyond the borders, the Chola, the Pandya, the Satiyaputra, the Keralaputra, up to Tamraparni and where the Greek King Antiochus rules, and among the kings the neighbors of Antiochus are everywhere Piyadasi has made provision for two types of medical treatment: medical care for humans and medical care for animals. Where medicinal herbs for treating humans or animals were not available, I introduced them and had them planted. "

Road network

“I had banyan trees planted along the streets to provide shade for people and animals, and I had mango groves planted. Every eight kroṣa I had wells dug and rest houses built, and watering points for people and animals set up in various places. But these are only minor achievements. Such things have been done before by kings to make people happy. I did it for the purpose of people practicing the Dharma. "

Messenger of the Dharma

“There were no Dharma Mahamatras in the past, but such messengers were named by me thirteen years after my coronation. Now they are working among all religions to publicize the Dharma and take refuge in the Dharma for the well-being and happiness of all. They work among the Greeks, the Kamboja, the Gandhaern, the Rastrika, the Pitinika and other peoples on the western borders. They work among soldiers, princes, Brahmanas, the haves, the poor, the elderly and those who practice the Dharma - for their well-being and happiness - so that they are free from suffering. "

See also

literature

- Ludwig Alsdorf : Aśokas Separatedicts from Dhauli and Jaugaḍa (= treatises of the humanities and social sciences class of the Academy of Sciences and Literature in Mainz. Born 1962, No. 1).

- Jules Bloch : Les inscriptions d'Asoka (= Collection Émile Senart. 8, ISSN 0184-718X ). Les Belles Lettres, Paris, 1950.

- Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli , Giorgio Levi della Vida (ed.): Un editto bilingue greco-aramaico di Aśoka. La prima iscrizione greca scoperta in Afghanistan (= Serie orientale Roma. Vol. 21, ZDB -ID 357188-9 ). Con prefazione di Giuseppe Tucci e introduction di Umberto Scerrato. Istituto italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente, Rome 1958.

- Shravasti Dhammika: The Edicts of King Asoka. An English Rendering (= The Wheel Publication. No. 386/387). Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy 1993, ISBN 955-24-0104-6 .

- Eugen Hultzsch (Ed.): Inscriptions of Asoka (= Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum . 1). New edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1925, ( digitized version ).

- Ulrich Schneider: Asoka's great rock edicts (= Freiburg contributions to Indology. 11). Critical editing, translation and analysis of the texts. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1978, ISBN 3-447-01953-0 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ The Edicts of Emperor Asoka. From the growth of inner values. Translated from the Prakrit and introduced by Wolfgang Schumacher. 26 "Bodhi-Blätter" A series of publications from the House of Reflection CH - 9115 Dicken 1991, online

- ↑ Gauranga Nath Banerjee: Hellenism in Ancient India. 1st edition, 1919, Mittal Publications, Reprint New Delhi 1995, p. 12 ( [1] on books.google.de)