Aśoka

Aśoka or (in the English-speaking world) Ashoka ( Sanskrit : अशोक , Aśoka ; actually Aśokavardhana (Sanskrit अशोकवर्धनाः aśokavardhanāḥ ); * 304 BC in North India ; † 232 BC ; also: Aśoka Adiraja - First King Ashoka) was a ruler of the Indian dynasty of the Maurya . He ruled from 268 to 232 BC. And was a grandson of the founder of the dynasty Chandragupta Maurya , who laid the foundations for the largest empire of ancient India in the northeast Indian empire Magadha (area of today's Bihar ) and the heartland of early Buddhism .

Life

Chandragupta ruled from about 317 to about 297 BC. BC. He was succeeded by his son Bindusara . He was followed again, according to the current state of research in 268 BC. BC, his son Ashoka as the third ruler of the Maurya dynasty. Before Ashoka came to power, he was his father's governor in the city of Taxila in the north-west of the empire.

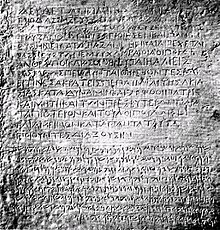

Initially, Ashoka was concerned with expanding the growing empire through new conquests, sometimes with extreme harshness. The last stage on this way was the capture of Kalinga with the capital Toshali in the east of India (area of today's Orissa ) in 261 BC. Chr. After the bloody and costly submission Kalingas Ashoka was recognized in the face of suffering and misery that brought his conquests with from a mental crisis. The source for this is a personal testimony: a rock inscription that was made four years later; therefore a military victory is pointless, only the victory of the Dharma is important .

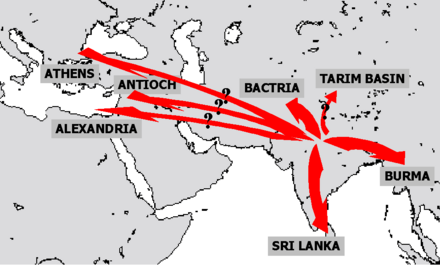

Ashoka appears shortly afterwards - at the height of his power around 258 BC. BC - having converted to Buddhism and decided to forego further conquests and to consolidate the empire. Perhaps he saw that conquering the large “white areas” of central and southern India would overstretch the empire's resources and plunge it into further wars such as the one over Kalinga. From then on, Emperor Ashoka, as a Buddhist lay supporter, dedicated himself specifically to promoting peace and social welfare. He forbade warfare and exhorted his subjects to refrain from using force (including by prohibiting bloody animal sacrifices and promoting vegetarianism ). Rejecting any aggression , from then on he strove for friendly relations with his neighbors such as the Seleucids and the Greeks in Bactria . However, Ashoka does not seem to have undertaken any fundamental reform of Indian society combined with a clear objective; rather, it was probably about establishing a standard of social behavior.

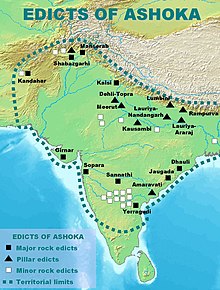

In his empire he placed the administration under state control, ended arbitrary taxation, promoted the fair distribution of land, built schools and hospitals (including animal hospitals) and based the principles of his on the teachings of Buddhism - possibly also on older Jain influences Spread politics across the country (through the so-called Pillar Edicts of Ashoka ).

But his measures also seemed to meet with resistance from the start. A rock edict begins with the words: "Virtuous deeds are difficult to do". In order to control the spread of the dhamma (Buddhist teaching) and to break the resistance, he appointed high officials as Dhamma-Mahamatras (chief inspectors of the Buddhist teaching). You should oversee teaching and doctrine observance.

Despite his religious concerns, Ashoka turned out to be a realpolitician. His actions reflect the contemporary separation between the wheel of Dharma (morality) and the wheel of the state . While he expressed his repentance throughout the empire for the atrocities during the conquest of Kalinga, he never thought of giving Kalinga back independence or of letting those abducted from there return. He even threatened resistance with death. In the rock edicts in Kalinga, on the other hand, there is nothing to be read of remorse, here he proclaimed his good intentions and his peacefulness by having the following chiseled in: "All people are like my children to me ... They should not be afraid of me and should trust me" . Possibly the crimes attributed to Ashoka before his conversion - they go as far as the charge of fratricide - are also an argument of Buddhist propaganda, which they greatly exaggerate in order to make the subsequent conversion all the more wonderful.

Under Ashoka, the empire was divided into five areas. In the center lay Magadha with the imperial capital Pataliputra . He centralized the administration of the great empire, which comprised a large part of the Indian subcontinent - with the exception of southern India. However, it must be taken into account that there were very large areas that were not covered by the central government, such as the large central Indian area. There is evidence of strict state control in the Yamuna area in particular. Little is known from texts about the late period of the Maurya Empire. Ashoka's successors did not have royal inscriptions written. Buddhist sources say that the symptoms of decay were already noticeable under Ashoka in recent years. The last member of the Maurya dynasty, Brihadratha, was born in 185 BC. . Chr by its General Pushyamitra Shunga murdered, who later introduced the forbidden Ashoka horse sacrifice again.

The rule of Ashoka was also, and above all, of great importance for Buddhism, which he tirelessly promoted while also respecting other teachings. Under his rule the teaching also gained a foothold in Sri Lanka . In addition, he sent the first religious embassies to Asia Minor , the Seleucid , Ptolemaic and Antigonid empires , to spread the word of the peaceful Buddhist message. However, it is uncertain whether Ashoka's envoy ever arrived in Egypt or Macedonia. Under his patronage in 253 BC BC or 250 BC . AD a Buddhist Council held by the Pataliputra (now Patna ), was called the capital of the Mauryan Empire.

Historically, Ashoka is considered to be one of the greatest rulers of ancient India and the first Indian ruler to introduce undisputed ethical concerns into politics. In India to this day he is revered as an outstanding example of just and peaceful politics.

Missions in the western cultural area

In the 13th edict of the rocks, the kings and thus areas were named to which Ashoka sent his missionaries:

- Amtiyoka, that was Antiochus II. Theos (261–246 BC) king of Syria;

- Turamaya, that was Ptolemy II Philadelphos (285–247 BC) of Egypt;

- Amtekina also Amtekini, that was Antigonus II Gonatas (276–239 BC) of Macedonia;

- Maga, that was Magas of Cyrene (around 300–250 BC);

- Alikasumdara, that was either Alexander II of Epirus (272-255 BC) or Alexander of Corinth (252-244 BC)

In the 2nd edict of the rocks only Antiochus II was mentioned and the other rulers were referred to as his Samantas (neighboring kings ). Ashoka sent Buddhist monks to the government seats of Hellenistic rulers.

Movie

The 2001 Bollywood film Asoka - The Warrior's Way borrows from the life of the ancient Indian ruler.

The ZDF documentary in the series Terra X Ashoka - The Indian Warrior Buddha recreates the life story of Ashoka.

literature

- Ludwig Alsdorf : Aśokas Separatedicts from Dhauli and Jaugaḍa (= treatises of the humanities and social sciences class of the Academy of Sciences and Literature in Mainz. Born 1962, No. 1).

- Devadatta R. Bhandarkar: Aśoka (= The Carmichael lectures. 1923). 4th edition. Calcutta University Press, Calcutta 1969.

- Harry Falk: Asokan Sites and Artefacts. A source-book with Bibliography (= monographs on Indian archeology, art and philology. 18). Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-8053-3712-4 .

- Hermann Kulke , Dietmar Rothermund : History of India. From the Indus culture to today. Special edition. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-54997-7 .

- James M. MacPhail: Asoka. The Associative Press et al. a., Calcutta et al. a. 1918 ( digitized version ).

- John S. Strong: The Legend of King Aśoka. A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ u. a. 1983, ISBN 0-691-06575-6 .

- Radhakumud Mookerji: Asoka. Macmillan and Co., London 1928 ( digitized version ).

- Anuradha Seneviratna (Ed.): King Aśoka and Buddhism. Historical and Literary Studies. Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy - Sri Lanka 1994, ISBN 955-24-0065-1 ( digitized version ( memento of September 23, 2012 in the Internet Archive )).

- Romila Thapar : The Penguin history of early India. From the origins to AD 1300 . Penguin Books, London a. a. 2003, ISBN 0-14-028826-0 .

- Romila Thapar: Aśoka and the decline of the Mauryas. With new afterword, bibliography and index. 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, Delhi a. a. 1997, ISBN 0-19-564445-X .

Web links

- Wilfried Stevens: King Ashoka - patron of Buddhism ( memento from August 9, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: onlinezeitung24.de, October 1, 2015

- Video Terra X : Ashoka - The Indian Warrior Buddha (ZDF documentary) in the ZDFmediathek , October 15, 2016 (video no longer available)

- Literature by and about Aśoka in the catalog of the German National Library

- The edicts of king Ashoka - The edicts of rock and pillars of Ashoka

- Ralf Berhorst: Buddha's husband in India. In: Spiegel. May 27, 2007

Individual evidence

- ↑ Elmar R. Gruber , Holger Kersten : The Ur-Jesus: the Buddhist sources of Christianity. Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main 1996, p. 92 f.

- ↑ On the dating of Ashoka's accession to power, see: Hajime Nakamura: A Glimpse into the Problem of the Date of the Buddha. In: Heinz Bechert (Ed.): The Dating of the Historical Buddha (= Symposia on Buddhism Research . 4, 1 = Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen. Philological-Historical Class. Volume 3, 189). Volume 1. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1991, ISBN 3-525-82476-9 , pp. 296-299; Kenneth R. Norman: Observations on the Dates of the Jina and the Buddha. In: Heinz Bechert (Ed.): The Dating of the Historical Buddha (= Symposia on Buddhism Research . 4, 1 = Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen. Philological-Historical Class. Volume 3, 189). Volume 1. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1991, ISBN 3-525-82476-9 , pp. 300-312, here 300; Pierre HL Eggermont: The Year of Buddha's Mahaparinirvana. In: Heinz Bechert (Ed.): The Dating of the Historical Buddha (= Symposia on Buddhism Research . 4, 1 = Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen. Philological-Historical Class. Volume 3, 189). Volume 1. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1991, ISBN 3-525-82476-9 , pp. 237-251, here p. 242 f.

- ^ Kulke, Rothermund: History of India. From the Indus culture to today. Special edition. 2006, p. 90.

- ^ Hermann Kulke, Dietmar Rothermund: History of India. From the Indus culture to today. Special edition. 2006, p. 86 f.

- ↑ Elmar R. Gruber , Holger Kersten : Der Ur-Jesus. The Buddhist Sources of Christianity. Non-fiction book 35590, Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main / Berlin, ISBN 3-548-35590-0 , p. 97.

- ↑ David E. Aune: Oral Tradition and the Aphorisms of Jesus. In Henry Wansbrough (ed.): Jesus and the Oral Gospel Tradition. Academic Press, Sheffield 1991, ISBN 978-1-8507-5329-2 , pp. 211-265.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Bindusara |

King of Magadha 3rd century BC Chr. (Chronology) |

Dasaratha |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ashoka |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Asoka |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | 3. King of the Maurya dynasty, emperor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 304 BC Chr. |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | North India |

| DATE OF DEATH | 232 BC Chr. |