Bet el-Wali

| Nubian monuments from Abu Simbel to Philae | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

| Porch of the rock temple |

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | i, iii, vi |

| Surface: | 374 ha |

| Reference No .: | 88 |

| UNESCO region : | Arabic states |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1979 ( session 3 ) |

Bet el-Wali ( Arabic بيت الوالي Bait al-Wali , home of the governor ), and Beit el-Wali or Dār el-Wali is an ancient Egyptian rock temples dating from the New Kingdom in Egyptian Nubia . The under King . Ramses II built, the gods Amun-Re , Re-Harachte , Khnum , Anukis , Isis and the deified king consecrated temple stood until the construction of the Aswan High Dam about 60 kilometers south of Aswan on the west side of the Nile , in an area which in ancient times was sometimes called Dodekaschoinos ("twelve-mile land").

In connection with the construction of the dam and the associated flooding of the site by Lake Nasser , the temple was cut into individual parts in 1964 by a team of Polish archaeologists, financially supported by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago and the Swiss Institute for Egyptian Building Research and Archeology in Cairo and dismantled. The reconstruction took place from 1965 to 1969 on the island of New Kalabsha about one kilometer southwest of the dam wall. There he is now northwest of the also offset Mandulis Temple of Kalabsha , both since 1979 on the World Heritage List of UNESCO .

description

Approximate coordinates of the original location: 23 ° 35 ′ 16 ″ N, 32 ° 52 ′ 00 ″ E

The first description of Bet el-Wali comes from Johann Ludwig Burckhardt , who traveled to Nubia in 1813. On March 28th of the year he reached the ruins of the temple near Kalabsha, the ancient Talmis , on the south face of a rock valley that flows into the Nile plain, the name of which, according to the locals, was Dar el Waly . The rock temple cannot be seen from the river. There was a quarry nearby , from which the building material for the Mandulis Temple of Kalabsha, built just 300 meters southeast of Bet el-Wali under the Roman Emperor Augustus, came. Numerous graffiti testify to further visits by early travelers to Egypt in Bet el-Wali .

In front of the Bet el-Wali, about 20 meters long and 8 meters wide, there were door cheeks with depictions of Ramses II and an inscription not to enter the temple in an unclean condition. They point out that in front of the temple building there was probably a pylon made of adobe bricks with a portal made of sandstone blocks, which was no longer there when Burckhardt visited it. The cheeks of the door are erected as an entrance at the current location of the temple on New Kalabsha. The dromos-like vestibule behind it was cut back into the mountainside and originally covered with stone ceiling tiles. When it was redesigned into a Coptic church in the 7th century, the room was vaulted with three parallel barrel vaults made of adobe bricks. This is evidenced by the semicircular incisions in the originally rectangular image field on the back wall, which Ramses II showed during acts of sacrifice.

The reliefs on the side walls of the vestibule, which today is thought to be the forecourt of the temple, show campaigns against Libyans, Syrians and Bedouins on the northwest wall, and the subjugation of the Nubians and their tributes on the southeast wall. The painting was completely destroyed by the removal of plaster casts, which the painter and draftsman Joseph Bonomi made in 1826 on behalf of the art collector Robert Hay . Colored copies of the reliefs are in the British Museum in London . It is noticeable that the Nubians were shown mixed with both red-brown and black skin color in the individual scenes.

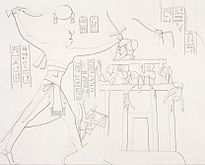

The northwest wall has five scenes depicting the king. At the side of the entrance to the sacrificial table room (left), Ramses II sits under a canopy and awaits the Asian prisoners brought before his four sons and high dignitaries, led by his eldest son Amunherwenemef . In the following scene on the right, the king, accompanied by a dog, subdues a Libyan. In the middle of the wall he rolls over his northern enemies with his chariot . This is followed by the conquest of a Syrian fortress, before a delivery of Asian prisoners, some of whom the king is already holding by the hair or standing on, completes the cycle of images towards the temple entrance.

|

|

|

|

Nubian tribute-bringers led by the Viceroy of Kush Amenemope (markings from the south-east wall of the vestibule) |

||

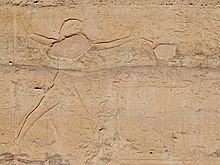

The reliefs on the south-east wall deal with two themes that are more extensive than the scenes on the opposite wall of the vestibule. On the left side facing the temple entrance, Ramses II, standing on his chariot, shoots his Nubian opponents with a bow and arrow. Some of them are already depicted falling under the king's horse. Others flee in the direction of a Nubian camp under dump palms , where a wounded man, supported by two companions, seems to have just arrived. Behind the king, the eldest son of Ramses II Amunherwenemef and below the fourth-born son Chaemwaset are shown in two picture registers , who support the father in battle on their own chariots. On the right half of the wall, in front of the entrance to the sacrificial table room, the king is sitting under a canopy like on the opposite wall. It is here that Nubian tributaries bring him donations, including live animals. In the upper register, Amunherwenemef stands in front of a richly laden shrine and behind this is Amenemope, the viceroy of Kush (Nubia), who was awarded the honor gold , between two servants anointing him. Amenemope is also shown in the lower register, with a carrying bar with Nubian products.

Three portals at the rear of the vestibule, the two on the sides of which were added later, lead into the 10.4 × 4.15 meter large sacrificial table. The inner pillars of the portals depict the king in an embrace with Horus of Miam ( Aniba ) and as the recipient of life through Atum . The approximately 3 meter high sacrificial table room is divided by two architrave-like rock ribs with these supporting Protodoric columns . Each of the two columns has two hieroglyphic columns on the sides and a square abacus at the top, in which royal cartouches are incorporated. The colors of the reliefs in the interior of the rock temple are still well preserved. The wall decoration shows Ramses II slaying the northern and southern enemies of Egypt on the inside of the wall with the three entrances and performing sacrifices in front of various gods on the side walls of the sacrificial table room. Vultures with outspread wings are depicted in the middle of the ceiling, symbolizing the goddesses Mut and Nechbet .

Wall niches are set into the back wall of the offering table room on both sides, in each of which three seat images were carved out of the rock. The left, southeastern niche shows Ramses II in a semi-sculptural manner between Horus of Baki (Kubân) and Isis, the right or northwestern niche between Khnum and Anukis. Through the position between the gods, the king symbolically takes on the role of the heavenly child of the respective gods. Oh, in the back wall of the 2.8 × 3.6 meter sanctuary , the “holy of holies” behind the offering table room, there is such a rock niche. However, this is empty. It is believed that when the Copts converted the temple into a church, the seat images were knocked out in order to use the rock recess as an altar niche. The reliefs on the walls next to the niche in the 1.7 meter high sanctuary show the gods Amun-Min and Ptah . On the back, on both sides of the entrance, Ramses II is represented as he is being nursed by Anukis on the left and Isis on the right .

The fine relief style of the vestibule and the floor plan of the building distinguish Bet el-Wali from the later Nubian temples of Ramses II south of Kalabsha. Part of the decoration is still made in high relief, as was customary in the time of Seti I , the father of Ramses II. Most of the reliefs are sunk into the rock, but some are raised. In addition to the relief style, the representation or naming of only the first four sons of the king and the use of the short throne name of Ramses II, User-maat-Re (Wsr-m3ˁ.t-Rˁ) , a later modified early form, indicates a construction period In the first years of Ramses II's reign. This is the throne name in the cartouches at the temples of Abu Simbel User-maat-Re-setep-en-Re (Wsr-m3ˁ.t-Rˁ-stp.n-Rˁ) .

Further indications of an early construction period are the non-mention of the battle of Kadesch in the 4th year of Ramses II's reign, which takes up a lot of space in later temples, and the mention of Amenemope as Viceroy of Kush in the inscriptions, who was already mentioned under Seti I in the Office was and soon after Ramses II took over the rule of June or Hekanacht was replaced. As viceroy, he could have commissioned the construction or supervised the construction.

literature

- Walter Wreszinski ( edit .): Richard Lepsius : Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia. Fifth volume of text: Nubia, Hammamat, Sinai, Syria and European museums. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1913, pp. 12-17. ( Digitized version of the Lepsius project Saxony-Anhalt)

- Günther Roeder : The rock temple of Bet el-Wali (= Les Temples immergiés de la Nubie ). Imprimerie de l'Institut Français d'archéologie orientale, Cairo 1938.

- Herbert Ricke , George R. Hughes, Edward F. Wente: The Beit el-Wali Temple of Ramesses II . University of Chicago, Chicago 1967 (English, oi.uchicago.edu [PDF; accessed on August 16, 2015]).

- Joachim Willeitner : Abu Simbel and the temples of Lake Nasser. The archaeological guide . von Zabern, Darmstadt, Mainz 2012, ISBN 978-3-8053-4457-9 , Beit el-Wali, p. 27-31 . ( Digital version of the table of contents).

Web links

- Temple of Beit el-Wali - The rock temple of Ramses II

- Beit el-Wali rock temple

- The temple of Beit el-Wali

- The Temple of Beit el-Wali in Nubia (English)

- Beit el Wali (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Alberto Siliotti: Abu Simbel and the temples of Nubia . American University in Cairo Press / Geodia, Verona 2002, ISBN 978-977-424-745-3 , The Temple of Beit el-Wali, p. 28 (Italian: Abu Simbel ei Templi della Nubia . Verona 2000. Translated by Iris Kühtreiber).

- ↑ Klaus Adams: Bet el-Wali (temple). www.aegyptologie.com, 2003, accessed on August 14, 2015 .

- ^ Joachim Willeitner : Abu Simbel and the temples of Lake Nasser. The archaeological guide . von Zabern, Darmstadt, Mainz 2012, ISBN 978-3-8053-4457-9 , p. 13–14, 27 ( digital version [PDF; 2.7 MB ]).

- ^ Joachim Willeitner: Abu Simbel and the temples of Lake Nasser. The archaeological guide . von Zabern, Darmstadt, Mainz 2012, ISBN 978-3-8053-4457-9 , p. 27 .

- ^ Johann Ludwig Burckhardt : Travels in Nubia . Weimar 1820, p. 174 ( limited preview in Google Book Search - English: Travels in Nubia . London 1819.).

- ^ Roger O. de Keersmaecker: Travelers' graffiti from Egypt and the Sudan. Volume 10: The Temple of Kalabsha. The Temple of Beit el-Wali . Graffito Graffiti, Mortsel (Antwerp) 2011.

- ↑ a b c Joachim Willeitner: Abu Simbel and the temples of Lake Nasser. The archaeological guide . von Zabern, Darmstadt, Mainz 2012, ISBN 978-3-8053-4457-9 , p. 27-28 .

- ↑ Mohamed Hossam Abdel Wahab: The image program and the spatial function in the Nubian rock temples of Ramses' II. Dissertation University of Heidelberg. 2014, p. 15 ( digital version [PDF; 6.0 MB ; accessed on August 22, 2015]).

- ↑ a b c Joachim Willeitner: Abu Simbel and the temples of Lake Nasser. The archaeological guide . von Zabern, Darmstadt, Mainz 2012, ISBN 978-3-8053-4457-9 , p. 28-29 .

- ^ Officials - Sethos I. -. Amenemope (Jmun-m-Jp.t) - Viceroy of Kush -. www.nefershapiland.de, April 11, 2013, accessed on August 27, 2015 .

- ↑ a b c d Joachim Willeitner: Abu Simbel and the temples of Lake Nasser. The archaeological guide . von Zabern, Darmstadt, Mainz 2012, ISBN 978-3-8053-4457-9 , p. 30-31 .

- ^ Dieter Arnold : Lexicon of Egyptian architecture . Albatros, Düsseldorf 2000, ISBN 3-491-96001-0 , p. 41 .

- ↑ a b Mohamed Hossam Abdel Wahab: The image program and the spatial function in the Nubian rock temples of Ramses' II. Dissertation University of Heidelberg. 2014, p. 14 ( digital version [PDF; 6.0 MB ; accessed on August 22, 2015]).

- ↑ Christine Raedler: On the representation and realization of pharaonic power in Nubia: The Viceroy Setau . In: Rolf Gundlach, Ursula Rößler-Köhler (Hrsg.): The monarchy of the Ramesside period: Requirements - Realization - Legacy . Files of the 3rd symposium on the Egyptian royal ideology in Bonn 7–9 June 2001 (= Egypt and Old Testament ). tape 36, 3 . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2003, ISBN 3-447-04710-0 , On the viceroys of Kusch in the early Ramesside period, p. 131 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Giovanna Magi, Patrizia Fabbri: Abu Simbel: Aswan and the temples in Nubia . Bonechi, Florence 2007, ISBN 978-88-476-2033-9 , Beit el-Wali, p. 96 .

Coordinates: 23 ° 57 '42.6 " N , 32 ° 51' 58.8" E