Battle of Kadesh

| date | 1274 BC Chr. |

|---|---|

| place | Kadesch on the Orontes |

| output | Retreat by Ramses II. |

| consequences | Later peace treaty under Ḫattušili III. |

| Peace treaty | 1259 BC Chr. |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Hittites |

|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 20,000 men, 2,000 chariots |

37,000 men 3,500 chariots |

| losses | |

|

high |

medium |

The battle of Kadesh between the Egyptians and the Hittites took place in the fifth year of the reign of Pharaoh Ramses II , 1274 BC. BC at the fortress. Kadesh (also Qadesh or Qades ) on the river Orontes place in western Syria near the present Syrian- Lebanese border. After the battle of Megiddo , she is Thutmose III. 1457 BC BC denied the second known major battle in Egyptian ancient world history.

Testimonies of the battle

The course of the battle is documented by both Egyptian and Hittite sources. However, the campaign of Rameses II, which led to the battle of Kadesh, is known almost exclusively from the perspective of the Egyptians involved. The outcome of the battle is portrayed as a victory in the Egyptian sources: the king, who had been abandoned by his troops, was able to achieve victory with the help of the god Amun . Three versions of the representation of the events are in the temples of Karnak and Luxor , two in the Ramesseum and more in his temples of Abu Simbel , Abydos and Derr. In addition, descriptions on papyri have been preserved, so that there are a total of 13 versions.

The Hittite descriptions are preserved in Babylonian cuneiform on clay tablets and were found in the ruins of Hattuša . The reason for the few historical Hittite sources for this most famous military conflict in the Near East is assumed to be the relocation of the capital by Muwattalli II , who relocated it from Hattuša to Tarhuntassa . His successor, in turn, moved the capital from Tarhuntassa back to Hattuša. A large part of Muwattalli's records from his reign were not taken into the archives in Hattuša, but remained in Tarhuntassa. This explains the significant decline in historical sources during Muwattalli's reign. The exact location of the city of Tarhuntassa is still uncertain today.

Reconstruction of the events

Before the battle

The city of Kadesch had been fought over since the 18th Dynasty in the New Kingdom and was already by Thutmose III. captured on his sixth campaign. The cuneiform tablets, the so-called Amarna letters , found in Akhenaten's newly founded capital Akhet-Aton , provide further information about Egypt's relationship to its vassal states in the Middle East and the Hittites. The threat to the Mitanni empire by the Hittites fell during his reign and the defection of the small states Amurru (under Prince Aziru ) and Kadesh (under Prince Aitakama ) in his last years of reign. The great loss of Egyptian supremacy in central Syria only occurred after Akhenaten.

Akhenaten's reign and that of his successors caused turmoil within Egypt, in which the land of Egypt had not perceived the influence established by the first kings of the 18th dynasty in Syria. When Seti I set out on his first Asian campaign, the pacification of Palestine was his first goal. His campaign continued to Lebanon, where he secured the entire hinterland for a new confrontation with the Hittites. Only on a later campaign did he successfully attack Amurru and Kadesh. His reliefs in Karnak and his victory stele from Kadesch tell of this. However, the reconnection of Amurru and Kadesh did not last long and the Hittites regained their Syrian provinces. But since the Hittites did not advance further towards Egypt, the Egyptologists assume a tacit agreement between the two rulers, which amounted to a non-aggression pact.

The goal of Ramses II was to break the Hittite alliance system and to push back the influence of the Hittites. So he started his first Asian campaign in the summer of his fourth year of reign (1276 BC) and recaptured Amurru, located in northern Lebanon, under King Bentešina , which again bordered the Egyptian sphere of influence on Ugarit . His steles in Byblos and on the Nahr al-Kalb report on the event. Through this advance, the Egyptians put forward their claim to Syria, which was under the rule of the Hittites. The Hittite Empire under King Muwattalli II , son of Mursili II , reacted and the following year saw the most famous battle in ancient Egyptian military history.

The opponents

In this battle Ramses II and the Hittite King Muwattalli II faced each other for the first and only time. For this battle, Ramses raised the largest army that, as far as we know today, had ever existed in Egypt until then. It consisted of chariots and foot troops. The light chariots were manned by two soldiers each. The army consisted of around 20,000 men in four divisions (combat units of mixed troops). These were named after the main Egyptian gods Amun , Re , Ptah and Seth . The ranks of the army also included Nubian soldiers and elite units of the Shardana , foreign mercenaries whom Ramses II had accepted into the Egyptian army. The main armament were composite bows with an effective range of 90 m and cutting weapons made of bronze .

The Hittite army consisted of around 37,000 men, mainly foot troops. Muwattalli's army also included many traditional enemies of Egypt, including the kings of Naharina , Arwad, Karkemish , Kadesh, Ugarit and Halpa . The countries of Asia Minor, such as Kizzuwatna and Pitassa, which were subordinate to the Hittite Empire , also had to provide their contingents. To further expand his army, according to Egyptian sources (Kadesh inscription P40-53), Muwattalli also recruited many mercenaries from different regions of Asia Minor and Syria: from Lukka , Maša , Kizzuwatna, the former Arzawa and Pitašša, among others . Also Kaskians from northern Anatolia and Dardany that are possibly with the Dardani can equate were involved in Hittite side in the battle. There were also 2,500 to 3,500 chariots. They were heavier and more immobile compared to the Egyptian chariots. This was shown, for example, in the fact that they were occupied by three men. The Hittites used their first cutting weapons made of hardened iron (steel).

The course of the battle

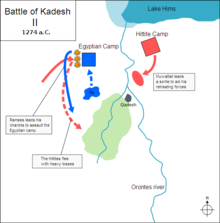

According to Egyptian reports, Ramses II was encouraged by the successes of his first "campaign of victory" to retake the city of Kadesh. He moved in early April 1274 BC. In his fifth year of reign from his north-eastern border town Sile in a northerly direction. This corresponded roughly to the same way that Thutmose III. through the Gaza area . The huge army, which also included sutlers and servants , made slow progress. Ramses II led the Amun division. It was followed by the other units Re, Ptah and Seth at a distance of 10 km each. In the Sharon Plain, a kind of reaction force separated from the army. This was to advance on the coast to the mouth of the Eleutherus and then from the west in the direction of Kadesch, while Ramses II marched there with the Amun division. He did not wait for the army that was behind and crossed the Orontes .

On April 20, 1274 BC Two Bedouins were picked up by Egyptian guards. The men declared that they wanted to defer to Ramses with their tribes:

"The wretched ruler of Hattusa sits in Halpa, he is afraid of the king of Egypt."

Ramses II did not doubt the truthfulness and immediately moved with the Amun unit in the direction of Kadesh. While the Re unit followed in a short distance, the Ptah and Seth units were still about 20-30 kilometers away and could not support the planned attack. Scouts intercepted two other spies of the enemy Hittites who were under torture that the statements of the two Bedouins were a ruse and that the Hittite army was in fact in the east near Kadesh.

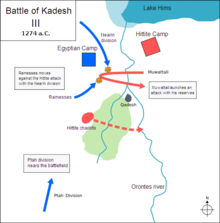

In the meantime, Muwattalli II sent 1,000 Hittite chariots over the Orontes and attacked the Re-unit . The Egyptians were completely taken by surprise and fled across the Orontes with great losses. The Hittites surrounded the camp of Ramses II, who was now in a catastrophic situation: He, his bodyguards and the Amun division were locked in while the Re unit was on the run and the Ptah and Seth units were still far away. Complete victory seemed certain to the Hittites until the strike force arrived that had taken the Palestinian coastal route. Although this unit could no longer reverse the course of the battle, it did manage to free Ramses II unscathed from the hopeless situation. Muwattalli II, who had not expected such rapid success, did not pursue the fugitives, but stayed with his army on the other bank of the Orontes. He returned with his units to the east bank of the Orontes. Ramses II no longer had enough soldiers to counterattack. He gathered his battered troops as well as the units Ptah and Seth who were not involved in the battle and began to retreat.

The end of the battle

Ramses II had not achieved his goal of conquering the city of Kadesh: the disputed area remained under Hittite influence. Amurru came back under Hittite sovereignty, whereby King Bentešina was deposed by Muwattalli, who named a new ruler. Despite the stalemate situation, Ramses had the events of the battle presented as a victory in an almost propagandistic way. In addition, these reports of the battle reveal the helplessness of the senior officers, as a result of which the military in the country clearly lost influence.

After the battle

The military weakness of the Egyptians at Kadesh did not go unnoticed by the Egyptian vassal states in the Syrian region. They then stopped paying their tribute to Egypt. Ramses II could not tolerate this and in the 7th or 8th year of his reign set out again on campaigns in the Syrian-Palestinian area: over Tire , Sidon , Beirut , Byblos and the valleys of Eleutherus and Orontes, he conquered Tunip and Dapur (see Battle of Dapur ). Muwattalli's successor Muršili III. did not intervene when Ramses advanced into Syria again. For Ramses II, all further campaigns after the battle of Kadesh were extremely successful.

The Hittites were less successful. In the meantime, internal unrest prevailed in the Hittite Empire and so it happened in 1264 BC. To a change of power: Muršili was by his uncle Hattušili III. dethroned and received political asylum in Egypt. The Assyrians also became a growing threat to the Hittites.

This situation moved Hattušili III. on the offer of peace negotiations with Egypt. More than 15 years had passed since the Battle of Kadesh. In the 21st year of Ramses II's reign (1259 BC) the clashes between Egypt and the Hittites were ended by the signing of the first known peace treaty ( Egyptian-Hittite peace treaty ). The contract is dated October 31. Excerpts or a copy of the contract can be found in the UN building in New York .

The peace treaty didn't just set commitments. He also caused the exchange of gifts from both royal families to each other and the proposal Hattušili III. to Ramses II to deepen the relationship by marrying one of his daughters. The alliance concluded with the Hittites was not violated by either side until the end of Ramses II's reign and lasted until the time of his successor Merenptah .

Ramses II did not carry out any further campaigns and began a brisk construction activity. The Hittite Empire collapsed barely a century later. At the same time Syria and Palestine were conquered by the " sea peoples " (among them the Philistines ), which also weakened Egypt.

See also

literature

- Katrin Schmidt: Peace through treaty: The peace treaty of Kadesch of 1270 BC BC, the peace of Antalkidas from 386 BC And the peace treaty between Byzantium and Persia of 562 AD. European Science Publishing House, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-631-38848-9 .

- Ernst Deissinger, Sascha Priest: When Pharaoh Ramses marched against the Hittites. dtv , Munich 2004, ISBN 3-423-34147-5 .

- Gerhard Fecht: Ramses II. And the battle of Qadesch (Quidsa). In: Göttinger Miscellen . (GM) Volume 80, Göttingen 1984, pp. 23-54.

- Gerhard Fecht: Supplements to my “The Poème about the Qadesch Battle”. In: Göttinger Miscellen. Volume 80, Göttingen 1984, pp. 55-58.

- R. O. Faulkner: The battle of Kadesh. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. (MDAIK). Volume 16, 1958.

- Birgit Brandau, Hartmut Schickert: Hittites, the unknown world power. Piper, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-492-04338-0 .

- Hermann A. Schlögl : Ancient Egypt. History and culture from the early days to Cleopatra. Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-54988-8 .

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Artemis & Winkler, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-7608-1102-7 .

- Jan Assmann : War and Peace in Ancient Egypt. Ramses II and the Battle of Kadesh. In: Mannheim Forum . No. 83/84, pp. 175-217.

Web links

- Thomas von der Way: Battle of Kadesch. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (eds.): The scientific biblical dictionary on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff., Accessed on September 1, 2011.

- Qadesh - A historic battle and the modern military command process

- Battle of Kadesh

Notes and individual references

- ^ Peter A. Clayton: The Pharaohs. Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1994, ISBN 3-8289-0661-3 , p. 151.

- ↑ a b c d Thomas Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. P. 230.

- ↑ A text transmission by Ramses II on the battle of Kadesch gives Thomas v. d. Way in Hildesheimer Egyptological contributions. (HÄB) 22, 1984.

- ↑ a b Hermann A. Schlögel: The ancient Egypt. Munich 2006, p. 284.

- ↑ a b Jörg Klinger: The Hittites. Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-53625-0 , p. 103.

- ↑ Hermann A. Schlögel: Akhenaten, Tutankhamun. Facts and texts. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, ISBN 3-447-03359-2 , p. 54.

- ↑ Erik Hornung : Fundamentals of Egyptian history. 6th edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2008, ISBN 978-3-534-21506-5 , p. 103.

- ↑ James Henry Breasted: History of Egypt. Parkland-Verlag, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-88059-128-8 , p. 241.

- ↑ s. on this, Trevor R. Bryce : The Kingdom of the Hittites. Oxford University Press, revised new edition 2005, p. 234f., On the Dardans p. 235 note 46.

- ↑ J. H. Breasted: History of Egypt. Stuttgart 1978, p. 242.

- ↑ On the 9th day of the 3rd month of Shemu (9th Epihpi); this is July 3rd of the Egyptian calendar; JD = 1256204 ; converted to the Gregorian calendar 2007 → deviation of the Egyptian calendar in 1274 BC Chr .: 68 days compared to the Gregorian calendar 2007. Birgit Brandau: Hittites, the unknown world power. P. 243.

- ^ Peter A. Clayton: The Pharaohs. Augsburg 1994, p. 150.

- ↑ a b Hermann A. Schlögl: The Old Egypt. Munich 2006, p. 282.

- ↑ In the specialist literature mostly given as November 21 ; corresponds to JD 1261877 = October 31 in the 2007 Gregorian calendar; this is the 21st Tybi in the Egyptian calendar (see here for calculation and explanation ).

- ^ Peter A. Clayton: The Pharaohs. Augsburg 1994, p. 153.

- ↑ J. H. Breasted: History of Egypt. Stuttgart 1978, p. 247.