Bhuta (spirit)

A Bhuta , Sanskrit bhūta, भूत even Bhut , belongs to a group of spirits or demons that in South Asia should appear well- or malevolent forms in humans. They often emerged from the souls of people who died unnaturally or who were not properly buried and move freely between the world of the dead and the living. Bhuta is a generic term for a large number of different spirits, some of which can cause obsession and illness, others are invoked as protective powers. A bhuta is male, the female counterpart is called a bhutin . Bhutas appear terrifying in human or animal form.

The belief in spirits is first mentioned in the Vedas , later in the Mahabharata and other ancient Indian epics. Many Bhutas have been integrated into Hindu popular beliefs and have adopted the characteristics of lower deities. As early helpers of Brahma , Bhutas enjoy a high status in some places and are honored as local protective deities. Rituals for Bhutas are at the beginning of the development of some Indian dance theaters such as Yakshagana in Karnataka and Teyyam in Kerala .

origin

The term bhuta in the sense of “formed”, “created” or “became” stands for natural forces in general in the early Sanskrit scriptures. In the beginning bhuta stood for "living beings", only later was the meaning of the word limited to the otherworldly beings. In some cases, Hindu gods were also attributed to these powers, such as Shivas Bhutisvara and Bhutanatha , "Lord of the Spirits". The syllable bhu can be traced back to the Indo-European language root be , which basically means “to grow”. In German the syllable bin is derived from this , in English be , in Serbo-Croatian biti , in Old Persian bavati and in today's Persian budan .

Since ancient Indian times, sacrificial rituals have been strictly defined in every detail of their course. People come into contact with the gods in order to work with them to ensure that the cosmogonic order of the world is preserved and that malevolent powers do not gain the upper hand. In the course of time, the Vedic sacrifice to the gods became, on the one hand, a personal and family ceremony ( puja ) in the Hindu temple , and on the other hand, its dramatic staging developed into a ritual theater organized with the same intention and with the same goals. While in this theater played for the gods the higher powers are presented in roles that tell a mythological story, at the climax of a theatrical performance bhutas can actually take possession of one or more bhuta characters. The transformation of the actor, previously indicated in a corresponding costume, ends in a dramatic dance of obsession.

The Bhuta cult is composed of an ancestor cult , a tree or snake worship, the worship of a local protective deity ( grama devata ) and other lower gods and in some regions includes the cult of the mother goddess . In Hinduism, the belief in Bhutas was mixed with the respective high gods and also created a connection between the ritual practices and beliefs of the different layers of the hierarchical caste society.

In the Vedic scriptures, the death ritual ( shraddha ) for the deceased ancestors is described with the offering of pindas (Sanskrit "part of the whole body", rice balls). It is a dramatic staging in which a Brahmin embodies himself in the role of ancestor ( pitar ) and accepts the gifts. According to the legislative mythical father Manu ( Manush Pitar , "father of humanity"), the ancestors are to be worshiped as divine beings. They deserve the pitar yajna , one of the five ritual sacrifices. The other four are bhuta yajna (sacrifice to the forces of nature), deva yajna (sacrifice to the gods), manushya yajna (sacrifice to humanity) and Brahma yajna (sacrifice to God Brahma ). Ancestor worship could also take place on a stone, tree or a cult idol erected for this purpose, i.e. at the presumed whereabouts of the ancestral souls. Other names for Vedic spirits were preta (dead), pishacha (carnivore), yaksha (nature spirit), especially yaksha naga (snake spirit ) and rakshasa (demon).

The memory of those living in the hereafter and the history of the spirit cult belong together, whereby two types of spirit beings are created depending on the cause of death, different in their relationship to humans. The ancestors, venerated as holy dead, died naturally and were buried with the necessary rites. After they die, they tend to carry on what they did in life: to protect their families and harm their enemies. They are confronted by the ghosts of people who have died unnaturally, i.e. through accidents, murder or suicide ( akal mrityu ). Even those not buried according to the rites have become strangers due to the lack of attention and behave accordingly hostile. Even the good house spirit can turn into a malevolent spirit through disregard and appear in dreams at night. Only the spirits of the second group are summarized as bhutas.

Spirit worship is probably older than the literary sources show. In the Rigveda , in addition to pitar , pishacha is mentioned in a verse , in the somewhat later collection of magical hymns, the Atharvaveda , and the associated Gopatha Brahmana , the carnivores appear in several places. In the Atharvaveda, Rudra is addressed as bhutapati , something like "Lord or protector of living beings". Spirits appear in the Mahabharata as well as in the Ramayana of Valmiki. When Sita learns that her lover Rama has been banished to the solitude of the forest by his father Dasaratha, she stops breathing heavily. Their behavior is described as a bhutopahata-citta , meaning “mind possessed by a mind”.

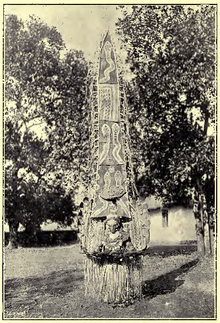

The Tamil work Shilappadhikaram from the Sangam period, written in the 2nd century AD, describes the art of dance and mentions rituals related to the Bhuta cult, which include singing, instrumental music and dance. The third chant says that colored bhuta images were venerated. In a ritual in honor of the king of the gods Indra in the fifth song, costumed women make offerings in front of the altar of the protective deity (Bhuta) to keep the malevolent powers away. The Bhuta altar consisted of an erected stone, as it is today in southern India.

According to the collection of legends Kathasaritsagara , written by Somadeva in the 11th century , King Chandraprabha had a fire sacrifice made for Rudra at the behest of the great demon Asura Maya when suddenly the bull Nandi appeared with a group of Bhutas and declared that Shiva had entrusted him with the leadership of the Bhutas. After Nandi received some offerings, he and the bhutas disappeared. History and a few more in this collection show that Bhutas were known and associated with Shiva in the 11th century.

characterization

When dealing with Bhutas, the precautionary measures customary in other cultures for comparable spirits apply. Young children and women are at risk, especially if they have just drunk milk. Women who have been married for the second time must fear that their former husband is harassing them as a ghost. Conversely, remarried men must reckon with unwanted appearances after the death of their first wife. On the other hand, it helps if the man wears the silver amulet saukan maura ("crown of the first woman") around his neck and, against her jealousy, offers the amulet all the gifts intended for the new woman before he passes them on.

Bhutas cannot sit on the ground because otherwise they would lose their power to the earth goddess. If Bhutas are to settle at certain shrines and places of worship, they need at least a raised seat in the form of stones or bricks stacked on top of one another. Accordingly, people are allowed to lie down to sleep well protected on the ground, and the deceased lie quietly on the ground until they are cremated. The well-known property that ghosts do not cast shadows also applies to bhutas.

Bhutas have an affinity for stone setting. In the cities of the Kathmandu valley there is the chvasa lhva . These are stones in the streets where people can get rid of objects that pose a magical threat, such as a dead person's clothes or the umbilical cord after childbirth. Such stones are venerated as meeting places of the Bhutas.

Individual forms

Vetala (also Betal, Baital) is considered the king of the Bhutas. He lives in cemeteries and takes possession of the living and dead bodies at will, which he brings to life. While not considered particularly aggressive, it can cause obsession and illness. In northern India he found tantrism together with Vasus (accompanying deities of Indra), Yakshas (nature spirits, lower gods) and Gandharvas (heavenly musicians) . In the Nepalese dance theater Mahakali pyakhan , which is performed annually in September at the great Indra Jatra festival in Kathmandu , vetalas are among the constant companions of the three goddesses who fight against the evil demons. Other bhutas, called cherapati , represent the personification of cholera in this performance.

Preta , also Pret ("died"), is another spirit of the dead who wanders around in the airspace of his home country from the moment of death until the arrival of the soul at its destination. According to the ancient Indian concept, Preta can be close to the living for up to a year, after which it enters the world of the fathers with a new body. The eldest son of the deceased makes simple sacrifices for the dead. In the villages there are small hills on which food and milk are placed. In some regions, preta can also be the ghost of a stillborn embryo if the necessary rites were not performed during pregnancy. In the earlier popular belief, infants did not need to be guarded from ghosts, since they themselves belonged to the Prets until they first ate grain. In Gujarat , a preta can speak through the mouth of a corpse. Eight kilometers north-west of the Gaya pilgrimage center in Bihar is the "spirit hill" Pretsila (Prethshilla), where the god of the dead Yama is worshiped. The believer prays on the top of the hill, facing south, where he suspects Yama's home on the horizon. The supplications are addressed to the ancestors who had to live as spirits and are now to accept offerings.

In South India the spirits of the dead are called Pret in Tamil peey . They are the ghosts of people who died as a result of special unfortunate circumstances (death in childhood, accident, suicide), which is why they move around unsteadily in the area of their home town. The Peey are bloodthirsty beings who attack people without warning and are particularly dangerous during some ritual acts. Only rituals that involve blood and death attract the peey. These include burials of the deceased from higher castes and temple festivals for the goddess Mariyamman . To protect them, in Tamil Nadu a group of Paraiyar, who form a socially lowest level professional caste of drummers, beats the frame drum parai .

Pishacha ("carnivore", from Sanskrit pishita , "meat") are carnivorous demons, malevolent spirits, which have emerged from an unnaturally dead liar, drinker, adulterer or general criminal. Like most bhutas, they can cause obsession and take any shape. Pishachas and pretas roam between cremation sites and battlefields and dance together. In Tibetan Buddhism , the pishachas appear as companions of the wrathful deity Kshetrapala ( Tibetan Zhing skyong , protector of the farmland, also in Hinduism). With the spiritual practice pishacha sadhana prophetic or clairvoyant abilities are to be acquired.

Demons and spirits are difficult to distinguish precisely, so the fundamentally malicious rakshasas mentioned in the Rigveda roam cemeteries at night, bring dead bodies to life, destroy offerings and passionately consume human flesh. The predatory animal beings have always fought against the gods and now live in trees. At least one of their malevolence is that they distract hikers from the path at night and otherwise cause them nausea and vomiting.

Three different demons in North India who are related to the Rakshasas are called Deo, Dano and Bir. The name Deo is derived from Deva (originally "heavenly" or "shining"), a group of 33 lower deities, later declined as the name for a cannibal demon, which is only prevented from causing greater damage by its extraordinary stupidity. Dano comes from Danava , a group of otherworldly beings who are known to date from pre-Aryan times and have always been the enemies of the gods. They are often associated with the same Daityas and Asuras .

Bir (derived from Sanskrit vira , "hero") was described as a malevolent village demon who harms people and cattle, today he appears with the honorary name Bir Baba (Baba is the respectful address for a male family member or an old ascetic) as a protective spirit of the dead. In the city of Varanasi and the surrounding villages alone there are hundreds of temple shrines and places of worship ( sthan , in this case bhuta sthana ) with aniconic stone settings or figurative reliefs for Bir Baba. In such places with platforms for offerings and mostly under large sacred trees ( pipal , bel and neem tree ), other spiritual beings are also worshiped: brahm (spirit of a brahmin ), mari and bhavani (spirits of a woman who died unnaturally) and sati (widow who was cremated with her husband's body). The basic question is whether Birs worshiped in this way should be counted in their essence among the Bhutas (spirits) or Devatas (deities). Due to their origin in the bodies of the unnaturally deceased, they belong to the Bhutas, they were unable to penetrate into the world of their ancestors ( pitri lok ), but in a second aspect they are counted among the devatas by the majority of the faithful. Their tragic fate has turned the Birs or bhuta-devatas into powerful beings ( malik ) who are able to fulfill human desires. In the countryside around Varanasi, the Birs act as protective deities ( dih, diha and diwar ). They are individualized by proper names and must be worshiped every morning before starting work. Even spirits ask permission from the patron deity before they are allowed to enter a village. Grama devata are the name of the protective village deities in all of northern India, similar ones also existed in the Bengali villages until they lost their importance at the beginning of the 20th century.

Churel (also Churail, corresponds to Sanskrit dakini ) is the dreaded female spirit of a woman from a lower class who died during her menstruation, pregnancy or giving birth to her child. The particular horror of this spirit stems from the situation of the woman, who is ritually unclean in the event of blood loss. In the past, menstruating women were not allowed to cook or do any housework, and access to some temples is still denied during this period. A churel mainly affects its own family, it shows up as a beautiful young woman with her feet twisted backwards. She mostly lives in the trees near cemeteries and kidnaps her victims into the mountains until the priest has made a sacrifice for them. To whom she has afflicted, she appears again and again in dreams, answering her at night can mean death. With the Bhil in western central India, bracelets on the right arm, consisting of a blue thread with seven knots, tied by a necromancer while he spoke magical formulas, helped against the female spirit and against some women possessed by the spirit.

The worst spirit of the dead was called Dund or "headless rider", he was on the move at night as a torso on a horse with his head in front of him on the saddle. There are innumerable folk tales in northern India about the deeds of the headless horsemen, once a whole army is said to have fled in panic when a dund appeared. In Bengal the end of the 19th century attracted related figures around the skandhahata were called. Headless, but with long arms, they rolled over the floor at night.

In contrast, Bhuta stands as a protective power. The names of various Bhutas such as Nandalike daiva (patron deity of the village), Bobbarya (patron god of fishermen) and Berme (also Birme, Bemme) are mentioned in numerous South Indian writings of the 16th century . With the honorable suffix –ru , the name becomes Bermeru or Bemmeru. This bhuta comes from the environment of Brahma and is therefore at the top of the bhuta hierarchy. Occasionally his name even takes the place of the high god. In the Indian epics, Berme watches over the fate of the heroes. In the Tulu- speaking area in the south of Karnataka he is depicted in the shrines as a warrior on a horse and with a sword in hand. In the Tulu legend Siri paddana , his name occasionally stands for a certain hero such as Berme Alva (Berma Alveru). The story of the lower female deity Siri forms the background for the annual Siri jatre possession ritual , which occasionally takes place together with Bhuta kola performances.

In the Mahabharata, Draupadi is a virtuous princess and wife of the five Pandavas . In the Tamil version of the epic, the stories about the daughter of King Drupada take center stage. As Draupadi Amman, she rises to the rank of goddess in South India, who is occasionally equated with Durga or Kali . Temples for Draupadi can be found in the federal states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. At temple festivals in Kerala such as the Patukalam ceremony, an army of Bhutas belonging to Shiva protects the goddess Draupadi. The ranks of this Bhuta troop even include Kauravas, who appear as opponents of the Pandavas in the original Sanskrit epic. One of the guardian bhutas in the Patukalam ceremony is Iravan (also Iravat, Aravan), a son of Arjuna and his wife Ulupi. Menacing figureheads from Iravan are revered as guardians in Draupadi and Mariamman temples.

Obsession and Illness

If someone suddenly becomes ill or shows previously unknown behavior and causes mischief, according to popular belief in Rajasthan a vir (such as bir , Hindi and Rajasthani , "hero") has hit him. If a person dies in a heroic deed, he returns after death as a Vir and, like the bhut, takes possession of the body of a living person. For example, Jhunjharji, a greatly revered hero, was a warrior who lost his head in battle and yet kept fighting and killing enemies until he finally fell to the ground. A special form of the vir is the bavaji in Rajasthan . He also died during a great deed ( mota came, hunt, raid or battle), but was reborn as vasak ("snake", Sanskrit vasuki ). The bavaji is worshiped at a shrine with a snake image on a stone and there, in an invocation ceremony ( coki ), asked to come temporarily into the body of a healing priest ( bhopa ). This opens up the possibility for the community present to establish a linguistic connection with the bavaji in order to receive help from him for all kinds of problems.

At such an invocation ceremony for the Mina, an ethnic group in southern Rajasthan, two singers appear in front of the snake portraits after paying homage and accompany each other on the hourglass drum dhak and a thali as a flat gong . After a while the bhopa begins to tremble violently and make faces. The bhopa , now possessed by the spirit, treats one by one the illnesses from the group of people who have gathered around him. As before, he rattles noisily with iron chains that he is holding in his hands. The bhopa calls someone from the group who has to lie on the floor in front of him. With circular movements, the bhopa screams and runs a knife over the patient's stomach and back and hits him in many ways. Other patients described their misfortune to the bhopa before the treatment. When the sick person begins to tremble, the bhopa has proven that there is a bhuta in him. He learns the name of the spirit (a recently deceased) from the sick person's mouth. Therapy consists of moving a nail over the patient's body seven times and then hammering that nail into a tree. The spirit was thus driven out and pinned securely to the tree.

Jagar is an all-night obsession ritual performed in the Garhwal and Kumaon regions on the southern edge of the Himalayas in a private home or in the square in front of a temple. The main actor and singer first hits a large animal skin with sticks, his blows getting louder and faster. At a private event he is accompanied by a hurkiya , which is a player of the hourglass drum hurka , at a public jagar a man plays the barrel drum dholki and another the small kettle drum dhamu . The beats are interrupted by occasional pauses in which one of the other participants begins to breathe in spurts and vigorously moves his upper body; until the first and later other participants fall into a trance. The person concerned suddenly jumps up from a crouch and begins to call out the name of the particular bhuta who has entered him. This can be the spirit of a deceased person or a mythical figure. The main actor improvises a sung speech to the bhuta while beating one of the drums. The possessed behave conspicuously, often holding their hands over a fire in the center of the square without being burned. The point is to ask the Bhuta for assistance in any emergency situation or to reconcile with him through the invocation and ultimately to persuade him to disappear, which requires an animal sacrifice.

Obsession and ritual theater

Rituals create a connection between the divine and the human world. In traditional Hindu rituals, a priest is involved who establishes access to the world beyond, ensures a quiet, controlled process, but does not represent himself as an acting divine power. The dramatic rituals of popular belief, on the other hand, present a deity or a spirit being with theatrical means. Often they show how the main character is gripped by a ghost. In a state of possession, the priest or the other persons involved have unusual abilities in that they can divine fortune, walk over hot coals without being burned or withstand knife attacks unscathed.

In contrast to the Hindu priests, who come from the Brahmin caste, the priests of the ritual drama mostly belong to the lowest strata of class society, but in the state of ritual obsession they are equated in status with the deities they embody. Like all transitional states, this state is considered dangerous; strict adherence to the ritual rules is therefore a necessary control mechanism.

Larger festivals, at which a ritual drama is organized, often employ members from several caste groups who, depending on the professional group, have certain tasks in preparation. The division is based on clearly defined hierarchical assignments and varies from region to region.

Bhuta kola

The main task of the Bhuta cult is to put people on the path of virtue and to punish those who do not want to adhere to the established order. In the Tamil epic Shilappadhikaram , the bhutas have adopted the order of human society and are organized into four castes , with correspondingly different clothing. In the Tulu -speaking region on the coastal strip to the south of Karnataka and north of Kerala , the Bhuta cult is the most popular form of popular religious worship and, according to literary tradition, is closely related to Hindu ideas such as honoring the dead ( shradda ), Vishnu cult and sacrifice to the gods in connection. For the language area Tulu Nadu , the oldest inscription from 1379 was found in Kantavar, in which low heavenly figures are mentioned.

Under Brahmanic influence, the pig-faced figure Panjurli Bhuta developed into the equally looking Varaha , an incarnation of Vishnu. Some simple folk spirits became vegetarians. Sanskrit verses ( shlokas ), which are recited as part of the ritual, and meditation practices ( dhyana ) have even made their way into the Bhuta cult . So the spirits were gradually accepted in the higher Hindu social classes.

In the Tulu folk tales and oral traditions, which mostly deal with agriculture, the family and the caste system, great importance is attached to the Bhutas as protectors of the land, the harvest and the people. In the mythical epics (in Tulu: paddanas ) the origins and characteristics of the Bhutas are told . This often happens in connection with bhuta performances called kola and nema . The performers of the ritual recite the verses alternately, accompanied by the small tembare hand drum . The paddanas are about pairs of opposites such as life and death, God and the devil, good and bad; they put the bhuta at the center, where the opposites come together in his characterization.

The origin of the Bhutas in Tulu Nadu is explained in a song. Accordingly, the supreme god Ishvara was sitting on his throne on Mount Kailasa when he was approached by his wife Parvati . She asked why there were sinful and decent people on earth. He told her that he created 1001 ganas and 1001 bhutaganas as his companions. Ishvara sent the Bhutas to earth with instructions to recognize people afflicted with diseases because of their sins and to lead them on the right path. The Bhutas took their assigned places on earth, as did the later subsequent Ganas. The main task of the bhutas is therefore to maintain social order. This is what the Bhuta ritual is about.

In 1872, two British people described in detail a magical bhuta ritual that was performed by the Billava (formerly mainly a caste of toddy collectors) and by performers of the Pombada caste near Mangalore . Pictures of the five bhutas that were to be evoked that evening were brought to the place of the event: the pig-faced Panjurli , the male-female hybrid being Marlu-jumadi , Sara-jumadi and, which emerged from Shiva and Parvati according to the Hindu tradition Kantanetri-jumadi and the horse called Jarandaya . Billava and the smaller communities of Pombada, Paravar, Kopala, Nalke and Panara practice the ritual dance Bhuta kola in the Tulu-speaking area , with the Bhuta performers embodying different forms of Bhutas according to the subtle differences in the social hierarchy of the individual groups. As described in the 19th century, the dancers appear with thick make-up, partly masked, with headdresses and colorful costumes. Once the bhuta demons have taken possession of the dancers, they turn violently in circles, make leaps or tremble with their upper bodies. The accompanying musicians belong to the Serigara caste, they form the most widespread village instrumental ensemble in Karnataka, which is simply called vadya after the Sanskrit word for "musical instrument" and they play the small double-headed cylinder drum tembare (or dolu ) das, which is hit with a bent stick Kesseltrommel paar sammela or the double-headed double-cone drum madhalam as well as the double reed instrument nadaswaram and the curved natural trumpet kombu . The rhythmic intensity of the music decisively encourages the dancer's obsession. The music is considered one of the offerings for the Bhuta. When the bhuta calls for food, quantities of rice and coconuts are brought.

Kola is a religious ritual that takes place on a set festival day. When the dancers are destined for Bhuta kola , a provisional stage (tamil pandhal , also pandal ) is set up at the selected location . In a procession, the ritual objects ( bhandara ) such as bhuta images, weapons and costumes are brought from the temple to the venue, accompanied by a drum player. The dancers can be made up according to the color scheme that applies to every Bhuta character, while women sing folk songs from the Tulu epics ( paddana s). After applying makeup, the dancer goes to a place on the stage where the ritual objects are kept. Here he receives anklets and a wide skirt made of palm leaf strips. He completes the first action dances in silence. After a short pause he steps back on the stage and with him a priest who is holding a sacred vessel in his hand. Immediately the dancer becomes possessed by a bhuta and begins to dance with the priest in a concentrated manner. The bhuta performer interrupts the dance and speaks in the voice of the bhuta, which forces those present to worship. They listen intently as the bhuta foresaw the future of the community and deliver his verdict on current disputes in the village. Not all Bhutas are heard in this way, so Nandigona, who is considered stupid, does not make any prophecies.

Bhuta kola contains all elements of dance theater including chants, costumes, masks, dialogues and a narrative plot. Ritual and dramatic play have the sole aim of pleasing the gods, devatas , bhutas and demons. In this sense, the Bhuta ritual is similar to the purvaranga theater prelude , as described in detail by Bharata at the turn of the century in his work on dance, music and theater Natyashastra . At the end of the ancient Indian theater, the actors pronounced the blessing on the king, the people present and the people who were not present. This is one of the many correspondences in the plot of Bhuta kola today . Something comparable to Bhuta kola can also be found in the fifth act of the play Malati-Madhavam by the playwright and Sanskrit scholar Bhavabhutis from the 8th century. Here gruesome, human flesh- eating demons ( pishachas ) appear, jump wildly and scream like jackals. The gruesome goddess Chamunda dances , and spirits belong to her group.

Jalata refers to a rare Bhuta ritual, a form of Bhuta kola , which is only performed by the Nalke community in two districts ( taluks ) in the Dakshina Kannada district . The event takes place on three to five days in March or April in the villages of Parappu (to Arasinamakki) and Parariputhila (to Puthila). In one scene, two ghosts of hunters appear. When they enter the stage, a red curtain is held up in front of them, lowered a little, raised again and finally pulled away with a swing. Now the impressively costumed ghosts can be seen sitting on chairs. The dance style with jumps and turns, the appearance with shouting and the dialogues presented with high voices are typical of many forms of entertainment theater in today's southern India.

Teyyam

Teyyam (also Kaliyattam) is a big festival for the eponymous deity in the region of Bhuta kola in southern Karnataka and northern Kerala. As in the Bhuta ritual, an actor in the main scene of the six-part performance is possessed by a higher power. The elements characteristic of the ritual drama resemblethose of Bhuta kola from the preceding puja to the final blessing of those present . The financial outlay to hold the event is extremely high, as the entire community, often thousands of people, has to be accommodated and fed for two to five days.

Yakshagana

Yakshagana is a cultivated dance theater style with mythical themes, the origins of whichliein the classical Sanskrit theater, in the narrative style Tala maddale and in Bhuta kola . With its religious acts at the beginning and at the end of the performances, the art of entertainment has remained recognizable as a ritual drama. Heavily made-up and costumed dancers appear; instead of the priest, a theater director and narrator ( bhagavata ) leads through each individual scene. He sets the pace for the accompanying musicians with a cymbal ( tala ), who play the double-cone drum maddale and the cylinder drum chande .

For the Yakshagana dance theater, the content and actions of the Bhuta kola were freed from their ritual character, whereby the transitions can be traced in detail. At the Bhuta kola there is a container for storing ritual objects at the performance location. Before that, a magic symbol is painted on the floor. Once the bhuta performer and his assistant have made up, they step in front of this diagram called oddolaga and then begin the dance ritual. In Yakshagana, oddolaga means the introductory dance when the main characters take the stage and outline the plot of the following drama. The aforementioned Bhuta ritual Jalata begins with a comparable first stage appearance. Jal-ata means something like "game in the forecourt".

Bhuta worship is associated with the cult of trees and snakes, the spirits often live in trees, and in their protective aspect they are often depicted on stones with snakes. The Nagas on the coast of Karnataka are worshiped in a ritual known as the Nagamandala ("snake circle"). The two dancing characters of the Nagamandala have similarities with the representation of the Bhuta kola and form another starting point for the Yakshagana theater.

More ritual theater

In Kerala, an ugly figure called a coolie appears in the Mutiyettu ritual theater as a counterpoint to the goddess Kali. The performers at the Teyyam wear make-up and headdress, at the popular ritual dance Gambhira in Bengal the dancers who are possessed by village spirits are masked. The masks help to bring both worlds, this and the other, together and are honored in the temple. In Bengal, Gambhira generally means place / festival for the worship of gods. Other Gambhira dances pay homage to the feminine energy in the form of Durga or Kali .

At Midnapur chhau in West Bengal , a rural and little-known form of Chhau dance theater, masked dancers depict bhutas in their malicious form, among others.

literature

- William Crooke: The Popular Religion and Folklore of Northern India. Vol. 1. Government Press, North-Western Provinces and Oudh, Allahabad 1894 Chapter: The Worship of the Malevolent Dead. Pp. 145-184 ( archive.org ). Reprint: Kessinger Publishing, Whitefish (Montana) 2004, ISBN 978-1-4179-4902-1

- Jyotindra Jain: Bavaji and Devi. Possession Cult and Crime in India. Europaverlag, Vienna 1973

- Farley P. Richmond, Darius L. Swann, Phillip B. Zarrilli (Eds.): Indian Theater. Traditions of Performance. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1990

- Uliyar Padmanabha Upadhyaya, Susheela P. Upadhyaya: Bhuta Worship: Aspects of a Ritualistic Theater. (Rangasthala monograph series 1) The Regional Resources Center for Folk Performing Arts, Udupi 1984

- Masataka Suzuki: Bhūta and Daiva: Changing Cosmology of Rituals and Narratives in Karnataka. In: Yoshitaka Terada (Ed.): Music and Society in South Asia. Perspectives from Japan. (Senri Ethnological Studies 71) National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka 2008, pp. 51-85

- Manohar Laxman Varadpande: History of Indian Theater. Loka Ranga. Panorama of Indian Folk Theater. Abhinav Publications, New Delhi 1992

Web links

- Bhutharadhane (Spirit Worship). classicalkannada.org

Individual evidence

- ↑ Shown in: Edgar Thurston: Caste and Tribes of Southern India. Volume VI - P to S. Government Press, Madras 1909, p. 141 ( archive.org )

- ^ Leon Stassen: Intransitive Predication: Oxford Studies in Typology and Linguistic Theory . Oxford University Press, New York 1997, p. 98

- ↑ Varadpande, pp. 44-46

- ↑ Rajaram Narayan Saletore: Indian Witchcraft . Abhinav Publications, New Delhi 1981, pp. 101f

- ↑ Crooke, p. 148

- ↑ Axel Michels: Śiva in Trouble: Festivals and Rituals at the Paśupatinātha Temple of Deopatan. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008, p. 180

- ↑ Crooke, p. 152

- ↑ Keiko Okuyama: Aspects of Mahākālī Pyākhan: In: Richard Emmert u. a. (Ed.): Dance and Music in South Asian Drama. Chhau, Mahākāli pyākhan and Yakshagāna. Report of Asian Traditional Performing Arts 1981. Academia Music Ltd., Tokyo 1983, p. 169

- ↑ Volker Moeller: The mythology of the Vedic religion and Hinduism. In: Hans Wilhelm Haussig , Heinz Bechert (Ed.): Gods and Myths of the Indian Subcontinent (= Dictionary of Mythology . Department 1: The ancient civilized peoples. Volume 5). Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-12-909850-X , keyword Preta , p. 146 f.

- ^ LSS O'Malley: Bengal District Gazetteer Gaya. 1906. New edition: Logos Press, New Delhi 2007, p. 71, ISBN 978-81-7268-137-1

- ^ Michael Moffatt: An Untouchable Community in South India: Structure and Consensus . Princeton University Press, Princeton 1979, pp. 112f

- ^ Robert Beer: Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs. Publishers Group UK, Lincolnshire 2000, p. 267, ISBN 978-1-932476-10-1

- ↑ Crooke, pp. 154-156

- ↑ Crooke, pp. 158f

- ↑ Crooke, p. 158

- ↑ Diane M. Coccari: Protection and Identity: Banaras Bīr Babas as Neighborhood Guardian Deities . In: Sandria B. Freytag (Ed.): Culture and Power in Banaras: Community, Performance, and Environment, 1800-1980. University of California Press, Berkeley 1989, pp. 130-134, 137-139

- ↑ Gram Devata. Banglapedia

- ↑ Crooke, pp. 168f

- ↑ David Hardiman: Knowledge of the Bhils and Theirs Systems of Healing. (PDF; 150 kB) The Indian Historical Review, Vol. 33, No. 1, January 2006, p. 210

- ↑ Crooke, pp. 160f

- ^ Ranajit Guha: Subaltern Studies: Writings on South Asian History and Society. Vol. 7. Oxford University Press, New York 1994, p. 183, ISBN 978-0-19-563362-7

- ^ Draupadi Temples in South India. Indian Net Zone

- ↑ Alf Hillebeitel: The Cult of Draupadi. Vol. 2. On Hindu Ritual and the Goddess. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1991, p. 176, ISBN 978-0-226-34047-0

- ^ Lindsey Harlan, The Goddesses' Henchmen: Gender in Indian Hero Worship. Oxford University Press, New York 2003, p. 15, ISBN 978-0-19-515426-9

- ↑ Jain, pp. 25f

- ↑ Meena Tribe, Rajasthan. Indian Net Zone

- ↑ Jain, pp. 27-33

- ^ Alain Daniélou : South Asia. Indian music and its traditions. Music history in pictures . Volume 1: Ethnic Music . Delivery 1. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1978, p. 48

- ↑ Phillip B. Zarrilli: The Ritual Traditions. Introduction. In: Richmond / Swann / Zarrilli (eds.), Pp. 123–126

- ↑ Varadpande, p. 46f

- ↑ BA Viveka Rai: Epics in the Oral Genre System of Tulunadu. (PDF; 382 kB) Oral Tradition 11 (1), 1996, p. 167f

- ↑ Varadpande, pp. 46-48

- ^ AC Burnell, Rev. Hesse: Description of a Bhuta incantation, as practiced in South Kanara (Madras Presidency). In: The Indian Antiquary. A Journal of Oriental Research. Vol. XXIII, 1872, pp. 7–11 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive )

- ↑ Gayathri Rajapur Kassebaum, Peter J. Claus: Karnataka. In: Alison Arnold (Ed.): Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. South Asia: The Indian Subcontinent. Vol. 5. Garland, New York / London 2000, p. 886

- ↑ Varadpande, p. 52f

- ↑ Purvaranga, Indian Theater . Indian Net Zone

- ↑ Varadpande, pp. 48-51

- ↑ Varadpande, p. 54

- ^ Wayne Ashley Regina Holloman: Teyyam. In: Richmond / Swann / Zarrilli (eds.), Pp. 132f

- ↑ Varadpande, pp. 54f

- ↑ Benoy Kumar Sarkar: The Folk-element in Hindu Culture. A Contribution to Socio-religious Studies in Hindu Folk-institutions. Longmans, Green and Co., London 1917, pp. 68 f. ( archive.org )

- ^ Gambhira Dance, West Bengal. Indian Net Zone