Charles Brady King

Charles Brady King (born February 2, 1868 on Angel Island , Marin County , California , USA , † June 22, 1957 in Rye , Westchester County , New York ) was an American engineer , volunteer in the American-Spanish War and the First World War I , entrepreneur , industrialist , musician , poet , architect , mystic and inventor with 64 patents, including 40 in the automotive sector. King, who was one of the earliest promoters of an automobile club and co-founded the first in the USA, is considered to be the inventor of the rivet hammer , of railway technology and one of the most important American automobile pioneers . He also went down in American folklore as the first person to drive a car in Detroit .

Origin and youth

King was the middle of three children of the Northern States - General John Haskell King (1820-1888) and Matilda Davenport King (1837-1912). His siblings died in childhood, the older sister Sarah Louise King (1866–1872) at the age of six, and his younger brother John Haskell King (1872–1875) at the age of three.

King began studying engineering at Cornell University , which he left without a degree in 1889 to work in Detroit .

Career

Riveting hammer

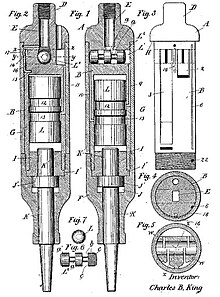

Just two years later, King was responsible for the booth at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago as the representative of his employer, the rolling stock manufacturer and timber industry supplier Russell Wheel and Foundry Company . Two of his inventions were presented: a riveting hammer , which was awarded a bronze medal at the trade fair, and a braking system for railroad cars .

It was at this exhibition that King first came into contact with automobiles. On display were Gottlieb Daimler's horseless carriage and three Benz Victoria imported into the USA by Émile Roger , Benz's Paris representative . 1893 was also the year in which the brothers Charles and J. Frank Duryea (1861–1938 and 1869–1967, respectively) offered their first motor vehicle for sale. This is considered to be the birth of the American automotive industry.

Representatives of the automobile industry

The founding of the first automobile club in the USA was also initiated by King. In a letter to the Chicago Times Herald dated October 8, 1895, he had proposed such an association to represent the interests of motorists. On November 1st - a few months after the first such club ever, the Automobile Club de France , the American Motor League was founded, which primarily campaigned for better roads. The founding members included King and the Duryeas and Elwood Haynes (1857-1925).

In November 1895, King was one of the passenger referees in the Chicago Times-Herald Race Contest , a reliability test officially recognized as the first automobile race in the United States. Originally around 100 participants registered, but only five started the race under the most adverse weather conditions and only two made it to the finish. Winners were the Duryeas, the second car was one of Oscar B. Mueller steered Mueller-Benz , the King had been randomly assigned as referee. Oscar Mueller and his father Hieronymus Mueller (1832–1900) had prepared the vehicle. King wrote a report on the memorable race that went down in American folklore as The Great American Horseless Race , which was published in December 1895 by The Motocycle [sic] magazine. In it he came to the following conclusion:

“This test has proven conclusively that no horse could have covered the course in the time that we did, and with the roads in such terrible conditions. This test is a valuable one to our army, and to the world. The endurance of these vehicles has been tested, they have come to stay ... "

“This test has clearly shown that no horse would have covered the distance in the time it took us and on roads in such bad shape. This test is valuable to our army, and to the world. The reliability of these vehicles has been tested; they came to stay ... "

The Mueller-Benz that he drove to the finish line in the last hour of the drive for Oscar B. Mueller, passed out from exhaustion and cold , was one of the three Benz Victoria that he had seen at the 1893 World Exhibition in Chicago.

The first car in Detroit

King was the first person to design, build, and demonstrate an automobile in Detroit . The vehicle was a motor buggy with a four-cylinder four - stroke engine , as it was later to become generally accepted. His first drive on the streets of Detroit on March 6, 1896 made automotive history. Followed by Henry Ford on a bicycle, King rode in front of hundreds of spectators down St. Antoine Street and Jefferson Avenue, across Woodward Avenue and Grand Boulevard, and back home, where he received a bus for public disturbance. Just three months later, Ford had its Quadricycle ready to take a test drive on public roads.

After this success, King sold the production rights to the engine of this vehicle to the Buffalo Gasoline Motor Company . This company later produced automobile engines; his 7 HP four-cylinder could also be purchased with a chassis. The customer had to take care of the petrol and water tanks and the body himself. Complete automobiles appeared in 1902. Production ended in 1903 following a lawsuit by the Electric Vehicle Company for infringement of its Selden patent . He sold the vehicle itself to Byron J. Carter , who later founded Cartercar .

The elder King sponsored many other pioneers such as ransomware Eli Olds , Jonathan D. Maxwell, and Packard Motor Car Company organizer Henry B. Joy . He advised Henry Ford on the construction of the Quadricycle test vehicle, which was tested in 1896, and helped out with components.

Charles B. King Company and first military service

In 1897, King founded a company with Henry Bourne Joy and his brother-in-law Truman Handy Newberry to manufacture pneumatic hammers, components for train brakes and marine engines. The three did military service during the American-Spanish War of 1898. King served as chief engineer on the auxiliary cruiser USS Yosemite until 1899 .

In 1900 Joy, Newberry and King dissolved their partnership. The marine engine building department was taken over by Olds Motor Works and managed by Charles King as managing director. Joy and Newberry then belonged to a group of investors which in 1903 organized the Ohio Automobile Company as the Packard Motor Car Company . Joy became its managing director and subsequently an influential member of the Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers (ALAM).

On March 9, 1901, the Olds plant burned down. The company was only able to save one of several technically different automobile prototypes from fire. For this little runabout with single-cylinder engine that was Model R developed and introduced in the same year on the market. It quickly became popular as the Curved Dash . King left the company shortly after the fire. With a partner, OJ Mulford , he took over the department again on his own account and formed the Michigan Yacht and Power Company from it .

Northern Manufacturing Company

In the meantime, a consortium of business people led by industrialists William A. Barbour and William E. Metzger had set up the Northern Manufacturing Company in Detroit. As chief engineer, they brought Jonathan Dixon Maxwell (1864-1928), who had designed the engine of the Curved Dash at Oldsmobile . Like King, he had left the company after the fire. He brought King to Northern as plant manager . The first vehicle was an automobile that in many ways can be considered a "better Oldsmobile Curved Dash". Maxwell left the company in 1904 to found the Maxwell Motor Company with Benjamin Briscoe . King succeeded him as chief engineer. Larger and modern two- and four-cylinder models were created under his responsibility, which were built parallel to the runabout. The two-cylinder remained in the program until the company was dissolved. Its special features include the remarkably early introduction of steering wheels and cardan drive . and the possibly first application of a three-point suspension of the engine in the chassis. The rearward inclined position of the engine reduced the load on the cardan shaft, which was gentle on it and made the vehicle quieter. These two-cylinder models are also among the first automobiles in which the engine and transmission form a unit. Up until now, it was common practice to mount both components separately in the chassis and to connect them to one another with a shaft . Alternatively, there were also rear axles interlocked with the gearbox; King also used this solution on the Northern 4-cylinder models.

At least for early two-cylinder models such as the 15 HP, there is evidence of a curious device that was supposed to blow the road dust backwards under the vehicle and thus keep it away from the passengers. In addition, the engine was given a particularly large flywheel , the back of which was shaped in such a way that it acted like a fan .

King also placed great emphasis on simplifying vehicle operation. Both the two- and four-cylinder cars managed without the usual gearshift and handbrake levers on the outside of the vehicle. They were accelerated and braked with a combined hand lever on the steering column. There was a foot pedal for the auxiliary brake and reverse gear, at least on models K and L. The clutch actuation on the two-cylinder is unclear. These vehicles had planetary gears , so a similar solution to that of the Ford Model T is obvious. It appears that King was able to put all the controls on the steering column in the Model C sedan of 1908.

The four-cylinder were upper-class vehicles with which the product range was expanded upwards. They received conventional three-speed manual transmissions. A clutch operated with air pressure was used, which according to the company's own information did not have to be readjusted. In addition, there were already pneumatic brakes that were operated "interactively" with the throttle (by hand), as well as a compressor for inflating the tires. The pneumatics were based on King patents. The engine was started with a mechanical ratchet instead of the usual crank.

In 1908 Northern was taken over by the Wayne Automobile Company in Detroit, which was controlled by the coachbuilder Byron F. Everitt (1872-?). Both companies were then transferred into a joint company, which was named after the new owners Everitt, William E. Metzger (1868-1933) and Walter E. Flanders (1871-1923) Everitt-Metzger-Flanders Company (EMF). The company is one of the forerunners of Studebaker automobile production.

King Motor Car Company

After leaving Northern , King went to Europe for two years, where he studied automotive engineering. Back in the United States, he founded the King Motor Car Company .

De Dion-Bouton brought out the first series passenger cars with V8 engines in 1910 with the DM, CJ and DN series . The first American car with such an engine was the Cadillac Type 51 , the engine of which was purchased by the Northway Motor and Manufacturing Company . The King Model D was the first American car with an in-house developed V8. It only appeared on the Cadillac for two months. Its side-controlled motor had a block made of cast aluminum. It made 60 bhp (44 kW).

In 1916, King gave up his position as chief engineer and made his services available again to the government.

Airplane engines and second military service

King initially served at McCook Field near Dayton, Ohio as head of engine development. It appears that he was involved in the development of the Liberty engine . Above all, however, he was given the task of getting the Bugatti U-16 aircraft engine , whose production rights the government had acquired, to work and preparing it for series production. The Duesenberg Motors Corporation in Elizabeth (New Jersey) was awarded the contract for production , where facilities and a test center were set up. King also worked here from 1918. The Bugatti engine, which is said to have structural weaknesses among other things, was finally ready for production at the end of the war. King's largely redesigned version, known as the King-Bugatti , was no longer needed and the order was canceled, resulting in the dissolution of Duesenberg Motors Corporation . The engine was a 16-cylinder in U-design with 24 liters displacement and in King's version with a weight of 550 kg and 420 bhp (313.2 kW) power. In the end, only 40 to 60 of these engines were built.

More inventions

King patented numerous inventions. Some work involves steam engines and steam powered devices such as steam shovels. His most important invention is the jackhammer . He also received patents in connection with motor vehicles, for example for improved ignition, gearboxes and suspensions.

family

Charles Brady King was married to Grace Fletcher (1860-1941). He died in Rye on June 23, 1957 at the age of 89 and was buried in Elmwood Cemetery , Detroit.

He was one of the last from the "Old Timers" club and thus one of the last contemporary witnesses to the pioneering days of the automobile.

Honors

- On January 26, 1925, Charles B. King was honored with a medal from the National Chamber of Commerce as "one of the most important contributors to the mechanical development of the automobile".

- Charles B. King received a Distinguished Service Citation Award from the Automotive Hall of Fame in 1940 .

- In 2007 he was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame .

Remarks

- ↑ Motocycle (written without r) is an early term for all types of motorized road vehicles. It was superseded early on by automobile and car or motorcycle (for motorcycles).

Works

- Charles B. King in The Motocycle Magazine. Chicago, December 1895: AN UMPIRE'S EXPERIENCE IN THE TIMES-HERALD RACE ON NOV. 28th. (Reprint; scroll)

- Charles B. King: A Golden Anniversary 1895-1945 / Personal Side Lights of America's First Automobile Race. Private print, 1945.

literature

- Hans Christoph von Seherr-Thoss : Dictionary of famous personalities in the automobile world. Ivy House Publishing, Raleigh NC, USA, 1st edition; 2005, ISBN 1-57197-333-8 .

- James J. Flink: America Adopts the Automobile - 1895-1910. MIT ( Massachusetts Institute of Technology ), 1970, ISBN 0-262-06036-1 .

- Beverly Rae Kimes : Pioneers, Engineers, and Scoundrels: The Dawn of the Automobile in America. Ed. SAE ( Society of Automotive Engineers ) Permissions, Warrendale PA, 2005, ISBN 0-7680-1431-X .

- William Pearce: Duesenberg Aircraft Engines: A Technical Description. Old Machine Press, 2012, ISBN 0-9850353-0-7 .

- Griffith Borgeson : The Golden Age of the American Racing Car. 2nd edition, 1998, published by SAE ( Society of Automotive Engineers ), Warrendale PA, ISBN 0-7680-0023-8 .

- Griffith Borgeson: Bugatti by Borgeson - The dynamics of mythology. Osprey Publishing Ltd, London, 1981, ISBN 0-85045-414-X .

- Don Butler: Auburn Cord Duesenberg. Crestline Publishing Co., Crestline Series. 1992, ISBN 0-87938-701-7 .

- Hugh G. Conway: Les Grandes Marques: Bugatti. Gründ, Paris 1984.

- The Automobile of 1904 ; Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly (January 1904), Americana Review, 725 Dongan Ave., Scotia NY (USA); published 1904.

swell

- Detroit Public Library , Automotive History Collection - King Papers

- Detroit Public Library, Burton Historical Collection - King Papers

- Cornell University Library , Archives Division - Charles King Papers

- Henry Ford Museum , The Ford Archives - Charles Brady King items

- Charles B. King: A Golden Anniversary 1895-1945 / Personal Side Lights of America's First Automobile Race. Private print, 1945

Web links

- American Automobiles: The King Automobile & The King Motor Car Co. (accessed February 2, 2019)

- Early American Automobiles: American Automobiles; Chapter 21. (accessed February 2, 2019)

- EyeWitnesstoHistory.com: America's First Automobile Race, 1895. (accessed February 2, 2019)

- Automotive Hall of Fame: Inductee Charles B. King. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- U.S. Patent No. 513,941: Charles B. King, Pneumatic Riveting Hammer . Patent from 1894. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- U.S. Patent No. 513,942; Charles B. King, brake for railway wagons. Patent from 1894. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- U.S. Patent No. 739,882; Charles B. King, Mechanism for electrical ignition systems, especially in connection with explosion engines. Patent from 1903. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- U.S. Patent No. 869,494: Charles B. King, Power Transmission . Patent from 1904. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- US Patent No. 786,790: Charles B. King, Pulley with Lubrication. Patent from 1905. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- U.S. Patent No. 786,448: Charles B. King, Steam Shovel . Patent from 1905. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- U.S. Patent No. 760,456: Charles B. King, Steam Dredge . Patent from 1905. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- U.S. Patent No. 799,169: Charles B. King, Valve Drive . Patent from 1905. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- US Patent No. 830,721: Charles B. King, Steering Mechanism for Self- Propelled Machines. Patent from 1906. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- US Patent No. 842,465: Charles B. King, Revolving Steam Engine. Patent from 1907. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- US Patent No. 857,002: Charles B. King, Power Transmission Device. Patent from 1908. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- US Patent No. 890,565: Charles B. King, Gear Shift and Reverse Mechanism. Patent from 1908. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- U.S. Patent No. 1,012,087: Charles B. King, Boom for Excavator (Steam Dredger). Patent from 1911. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- U.S. Patent No. 1,012,562: Charles B. King, Automobile Steering Gear . Patent from 1911. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- U.S. Patent No. 1,043,844: Charles B. King, Hydraulic Unloader. Patent from 1912. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

- US Patent No. 1,209,716: Charles B. King, Suspension with Springs for Vehicles. Patent from 1916. (English, accessed February 2, 2019)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c findagrave.com: Charles Brady King. (English, accessed February 2, 2019).

- ^ Charles Brady King's tombstone.

- ^ Seherr-Thoss: Dictionary of famous personalities in the automobile world. 2005, p. 87 (Charles Brady King).

- ↑ Flink: America Adopts the Automobile - 1895-1910. P. 144 (CB King).

- ↑ Flink: America Adopts the Automobile - 1895-1910. P. 23 (CB King).

- ^ Charles B. King in The Motocycle Magazine. Chicago, December 1895: AN UMPIRE'S EXPERIENCE IN THE TIMES-HERALD RACE ON NOV. 28th. In: Early American Automobiles: Duryea, The First American Automobile and 1895 Chicago Herald-Times Automobile Race. (English, accessed February 2, 2019).

- ↑ Flink: America Adopts the Automobile - 1895-1910. P. 19 (JD Maxwell, CB King).

- ^ King Motor Car Club, homepage. (English, accessed February 2, 2019).

- ↑ a b c d Automotive Hall of Fame: Inductee Charles B. King.

- ^ Beverly Rae Kimes, Henry Austen Clark, Jr: Standard Catalog of American Cars, 1805-1942. 1996, p. 159 (Buffalo).

- ↑ Flink: America Adopts the Automobile - 1895-1910. P. 298 (JD Maxwell, B. + F. Briscoe, CB King, HB Joy).

- ^ Beverly Rae Kimes, Henry Austen Clark, Jr: Standard Catalog of American Cars, 1805-1942. 1996, p. 807 (King).

- ↑ a b Kimes: Pioneers, Engineers, and Scoundrels. 2005, p. 111.

- ↑ Kimes: Pioneers, Engineers, and Scoundrels. 2005, p. 112.

- ↑ a b c Beverly Rae Kimes, Henry Austen Clark, Jr: Standard Catalog of American Cars, 1805-1942. 1996, p. 1046 (Northern).

- ^ Beverly Rae Kimes, Henry Austen Clark, Jr: Standard Catalog of American Cars, 1805-1942. 1996, p. 1523 (Wayne).

- ^ Georgano: Complete Encyclopedia of Motorcars, 1885 to the Present. 1973, p. 515 (Northern).

- ^ Beverly Rae Kimes, Henry Austen Clark, Jr: Standard Catalog of American Cars, 1805-1942. 1996, pp. 532-533 (EMF).

- ↑ coachbuilt.com: Briggs Manufacturing Co., 1909-1954. (English, accessed February 2, 2019).

- ↑ a b Jaap Horst: The Bugatti Revue: Bugatti Aircraft Engines. (English, accessed January 31, 2019).

- ↑ a b Jaap Horst: The Bugatti Revue: Bugatti License Aircraft Engines. (English, accessed January 31, 2019).

- ^ Butler: Auburn Cord Duesenberg. 1992, p. 83.

- ^ Borgeson: The Golden Age of the American Racing Car. 1998, pp. 114-115.

- ^ Pearce: Duesenberg Aircraft Engines. 2012, pp. 43–57.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | King, Charles Brady |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American automaker and inventor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 2, 1868 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Angel Island |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 22, 1957 |

| Place of death | Rye |