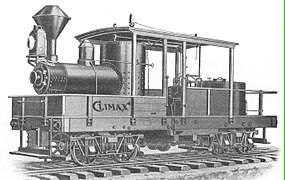

Climax locomotive

The Climax locomotive is a substructure of a geared locomotive , in which two steam cylinders work on a drive shaft train running in the middle under the locomotive, which drives the wheel sets in the bogies with outer frames via bevel screw gears. The name is derived from the Pennsylvania- based manufacturer Climax Manufacturing Company .

History and technology

The invention of the Climax locomotive is attributed to Charles D. Scott, who operated a forest railway near Spartansburg, Pennsylvania between 1875 and 1878 . The lumberjack of considerable mechanical ingenuity decided to launch the self-made steam locomotive he was using and took the drawings to the nearby Climax Manufacturing Company in Corry. The first four Climax locomotives were built and delivered in 1888. The patent for the design was filed in February of the same year and granted in December. Scott did not patent the invention himself, as he had little education, but left the drawings to his brother-in-law George D. Gilbert, who was a civil engineer and worked at Climax. Gilbert patented the invention in his name without mentioning Scott.

RS Battles of the Climax Manufacturing Company filed additional patents to improve the design, but Scott was again ignored. Scott filed a lawsuit against Gilbert and Battles, applying for a patent in his own name, which was granted to him on December 20, 1892 after a lengthy litigation. But the lawsuit left Scott penniless because he could hardly get any benefit from the invention.

The design bears the name Climax after the manufacturer, so that Scott as its inventor has practically been forgotten. Some publications refer to George D. Gilbert as the inventor of the design because the first patent was issued in his name.

The Climax locomotive was built almost entirely by the Climax Manufacturing Company , which was later renamed the Climax Locomotive Works . In addition, an agency with a service workshop was set up in Seattle , Washington state to sell and service locomotives for customers on the west coast.

After the Climax Manufacturing Company was no longer dependent on the patent of Gilbert due to the patents of Battles, the latter left the company and transferred his patent to the Dunkirk Engineering Company in the state of New York . This company built about 50 locomotives from the late 1889s or early 1890s, which were designated as the Gilbert type . Other locomotives were built by A & G Price in New Zealand .

In the second half of the 1920s, the demand for new forest railway locomotives had declined to a small extent compared to the previous years. At that time the owners of the Climax Locomotive Works were getting on in years, which led them to sell the plant to the General Parts Corporation in September 1928 . This company had specialized in the purchase of former motor vehicle manufacturers , for whose customers a spare parts service was offered. This was also the reason for taking over the Climax business. The new owner had no intention of continuing to build locomotives, so production ended after 40 years.

Between 1888 and 1928, between 1030 and 1060 locomotives were built.

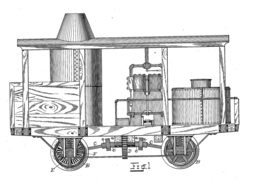

Patent from George D. Gilbert

The patent filed by George D. Gilbert in 1888 describes the propulsion of a forest railway locomotive. The drawing in the patent shows a flat car with a standing steam boiler , standing two-cylinder steam engine , water tank and fuel tank built on it. The invention concerned the chassis of the light rail locomotive with two-axle bogies, in which the drive shaft was arranged centrally above the wheel sets . The drive shaft train consisted of parts firmly mounted in the frame, which were connected to the parts mounted in the bogies via universal joint shafts . The steam engine worked on a manual transmission with two gears, which transmitted the power to the drive shaft. The patent was explicitly not limited to four-axle vehicles, but mentioned the possible expansion of the drive train to include additional bogies.

The differential gear described in the patent for transmitting the power from the drive shaft train to the wheels was only used in the very first Climax locomotives. Similar to an automobile , the power was transmitted separately to the two wheels of an axle, with one wheel firmly connected to the wheelset shaft and the other wheel being able to rotate loosely on a sleeve encompassing the wheelset shaft. The idea of differential gears was to reduce drag on tight turns by allowing one wheel to idle or rotate less than the one at the other end of the axle. The design did not prove itself because when driving at the adhesion limit compared to locomotives with rigid wheelsets, less traction could be exerted.

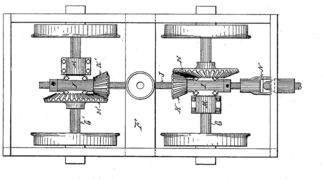

Rush S. Battles patents

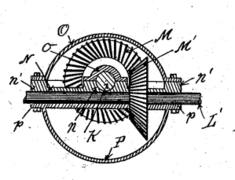

The 1890 Rush S. Battles patent is based on the invention filed by Gilbert, but in contrast to this, omits the differential gears. The normally designed wheel sets are driven by a simple open bevel helical gear per wheel set. Furthermore, the drive train in the bogies is mounted directly on the axles via a component known as a cross bearing. The cross bearing consists of two bearings arranged at right angles to one another in a housing, one of which encompasses the wheelset shaft and the other the longitudinal drive train.

A patent from Battles, also issued in 1890, applied the concept described above to a two-axle light rail locomotive.

In 1891, Battles filed a third patent by introducing a Climax locomotive, in which the drive shaft was driven by two horizontal cylinders. The locomotive corresponds to the early version of the B-Class.

Charles D. Scott patents

At the end of 1892, after the lawsuit, Scott finally received the patent for his successful invention, the Climax locomotive. The arrangement of the steam engine, boiler and two-speed gearbox corresponded to the Gilbert patent, while the drive without differential gear was described according to the Battles patent. This patent corresponds to the most common design of the A-class locomotives.

In 1893 Scott proposed a geared locomotive in which the frame under the boiler was articulated to the frame of the tender, similar to a support tender locomotive . The chassis under the boiler was permanently connected to it and was usually driven by lateral cylinders and coupling rods. Under the water and coal supplies there was a bogie which, like the Climax locomotives, was driven by a shaft running in the middle, which took the power from the foremost axle of the locomotive via a conical screw gear. For the first time, closed axle drives were proposed in this patent, the housing of which on the one hand protect the transmission from dirt and on the other hand contain the lubricant supply. There is no known locomotive of this type.

Geared locomotive with a supporting tender after Charles D. Scott

Climax locomotive compared to other types

In contrast to normal locomotives with side coupling rods, almost all geared locomotives had the advantage that the torque of the steam engine was transmitted more evenly to the track grid with the two rails due to the reduction. In contrast to the Shay locomotives , the vehicle structure was symmetrical around the longitudinal axis of the Climax locomotives, so that the center of gravity was roughly in the middle of the track axis. As a result, the boiler could also be made somewhat larger, which enabled more powerful, heavier versions.

Another advantage over the Shay locomotives was the fully sprung bogies. The Shay locomotives were on the side where the drive train ran, no springs, so that when distortions in the track tension losses einstellten or even derailed locomotives. This made the Climax locomotive superior to the Shay locomotive, especially for smaller forest operations, because it could also run on very poor tracks.

The heavier drive train of the larger C-Class locomotives could not initially be balanced, so that vibrations occurred on the crankshaft. The shaking was not transmitted to the rails due to the spring-loaded bogies, so it turned out to be particularly uncomfortable for the drivers, but did not damage the locomotive parts. Improvements at the end of production time eliminated these vibrations. The smaller types were not affected by the problem as the parts of the drive train were lighter.

Compared to the Heisler type , both the Climax and Shay locomotives had a large number of gears, which, at least in the older versions, were exposed to the elements without protection.

Classes

In the case of the Climax locomotives, a distinction is made between the following sub -types, known as classes :

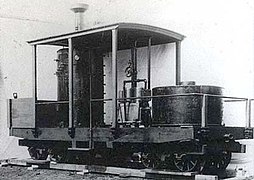

A class

The A-class locomotives had a standing steam engine with two cylinders, which was placed in the middle of the vehicle. The appearance of the locomotive resembled a flat car with a wooden body similar to a boxcar . They served to protect the drivers and the fuel from the weather - depending on the design, smaller or larger parts of the locomotive were covered. The steam boiler was in the front half of the locomotive in front of the steam engine.

The steam engine worked on a manual transmission with two gears, which transmitted the power to the drive shaft. The A-Class, together with some early versions of the B-Class, was unique in this regard, because shiftable transmissions were not used in Climax locomotives built later, nor in Shay or Heisler locomotives. The very first locomotives of the A-Class also had a differential gear, which drove the left and right wheels of an axle separately. This version was supposed to improve the cornering ability, but was quickly abandoned due to the loss of traction compared to rigid wheelsets.

The first four locomotives were designed as two-axle vehicles without bogies and without manual gearboxes.

A vertical steam boiler was used in smaller locomotives, while a so-called T-boiler was installed in larger models , which looked like a capital letter T on its side . The long boiler had a fairly small diameter and, together with the smoke chamber, formed the long limb of the T, which extended to the front end of the locomotive frame. The crossbeam of the T was formed by the standing boiler , which was located approximately in the middle of the locomotive, with the lower part reaching through the floor of the car. A sand dome was attached to the long boiler between the chimney and the standing boiler .

Climax A-Class locomotives were small locomotives that usually weighed no more than 17 tons.

B class

The B-Class Climax locomotives had more of the familiar appearance of a steam locomotive. The cylinders could be made longer and larger than in the A-Class because they were arranged along both sides of the boiler - horizontal in a few early locomotives, and inclined upwards 30 ° to 45 ° in most. The two cylinders drove a transverse jackshaft that worked via an angular gear on the longitudinal drive shaft in the middle of the vehicle.

Climax B-Class locomotives weighed between 17 and 60 tons.

C class

The C-Class Climax locomotives had three bogies. The third bogie was under a water tender that was articulated to the locomotive. This enabled the locomotive to be on the road for a long time without having to get hold of water. All C-class locomotives had inclined cylinders.

The locomotives weighed between 50 and 100 tons.

Preserved locomotives

23 Climax locomotives have been preserved, the condition ranges from wrecks lying in the forest to exhibits in museums to locomotives that have been prepared for operation. 17 locomotives have been preserved in North America , 4 in New Zealand and 2 in Australia . Five locomotives are operational, a sixth is to be added in spring 2018. [outdated]

| country | place | train | Serial number | Construction year | Discarded | class | Weight | Status | photo | source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Cleveland, Texas | The Retreat At Artesian Lakes | unknown | 1894 | 1965 | B. | 25 ton | not restored | ||

|

|

Eagle River, Alaska | Privately owned | 313 | 1902 | 1910 | A. | 15 ton | not restored | ||

|

|

Nome , Alaska | Tanana Valley Railroad | 399 | 1903 | 1926 converted to diesel operation | A. | 15 ton | disassembled | ||

|

|

Tokomaru, Horowhenua | Tokomaru Steam Museum | 522 | 1904 | 1954 | B. | 30 ton | Exhibit | ||

|

|

Cabin Creek, Washington | Privately owned | 804 | 1907 | 1944 converted to diesel operation | A. | 20 ton | Operational locomotive with gasoline engine and dummy steam boiler | ||

|

|

Marble Creek, Idaho | in the forest | 916 | 1909 | 1930 | B. | 48 ton | wreck | ||

|

|

Fairplex, California | RailGiants Train Museum | 932 | 1909 | 1955 | C. | 75 ton | Exhibit |

|

|

|

|

Duncan (British Columbia) | BC Forest Discovery Center | 1057 | 1910 | 1930 | B. | 23 ton | Exhibit |

|

|

|

|

Durbin, West Virginia | Durbin Greenbrier Valley Railroad | 1059 | 1910 | 1961 | B. | 55 ton | operational |

|

|

|

|

near Greymouth | Shantytown Heritage Park | 1203 | 1912 | 1968 | B. | 20 ton | operational since 1980,

backed up since 2002 |

||

|

|

Strasburg, Pennsylvania | Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania | 1237 | 1913 | 1956 | B. | 40 ton | Exhibit |

|

|

|

|

Te Awamutu , Waikato | Lions Club of Te Awamutu | 1317 | 1914 | 1956 | B. | 30 ton | Exhibit | ||

|

|

Pisgah Forest, North Carolina | Cradle of Forestry | 1323 | 1914 | 1956 | B. | 40 ton | Exhibit | ||

|

|

Duncan (British Columbia) | BC Forest Discovery Center | 1359 | 1915 | 1968 | B. | 50 ton | backed up operationally | ||

|

|

Cass, West Virginia | Cass Scenic Railroad State Park | 1551 | 1919 | 1960 | C. | 70 ton | planned operational from spring 2018 [obsolete] | ||

|

|

Lincoln, New Hampshire | White Mountain Central Railroad | 1603 | 1921 | 1952 | B. | 50 ton | operational |

|

|

|

|

Willits, California | Roots of Motive Power | 1621 | 1922 | 1956 | B. | 60 ton | backed up operationally | ||

|

|

Pukemiro, Waikato | Glen Afton Line Heritage Railway | 1650 | 1924 | 1969 | B. | 25 ton | under restoration to operational condition

(Status 2016) |

||

|

|

Hobart , Tasmania | Tasmanian Transport Museum | 1653 | 1923 | 1949 | B. | 28 ton | Exhibit | ||

|

|

Corry, Pennsylvania | Corry Historical Museum | 1681 | 1927 | 1956 | B. | 30 ton | Exhibit | ||

|

|

Felton, California | Roaring Camp and Big Trees Narrow Gauge Railroad | 1692 | 1928 | 1958 | B. | 50 ton | not restored

Last Climax locomotive built |

||

|

|

Elbe (Washington) | Mount Rainier

Scenic Railroad |

1693 | 1928 | 1968 | C. | 70 ton | operational | ||

|

|

Belgrave (Victoria) | Puffing Billy Railway | 1694 | 1928 | 1949 | B. | 25 ton | operational since 1988 |

Conversions

Some Climax locomotives, especially those of the A-Class, were later converted to diesel or gasoline locomotives. Some have been preserved in this form. During the conversion, the frame and drive train were retained while the steam boiler and steam engine had to give way to the new engine.

Garden railroad locomotive

In the Museum of Transport Switzerland is a garden locomotive in use, which was modeled on a B-Climax.

Movie

- In the cartoon series Thomas, the Little Locomotive , the character Ferdinand is based on a Climax C-class locomotive.

Web links

- Climax Geared Steam Locomotives. In: Geared Steam Locomotive Works. (English).

- Ed Vasser: Climax Locomotives. 1998 (English).

- 3D model of the 70 ton C-Class Climax locomotive Cass Scenic Railroad No. 9. (PDF;serial number 1551).

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Ed Vasser, Frankfort, Kentucky: History Of The Climax Locomotive. In: Climax Locomotives. Retrieved March 2, 2018 .

- ↑ Logging Railroad Era of Lumbering in Pennsylvania: Allegheny Valley logging railroads . Lycoming Printing Company, 1977 ( google.co.za [accessed March 11, 2018]).

- ^ Trains . Kalmbach Publishing Company, 1965 ( google.co.za [accessed March 11, 2018]).

- ^ A & G Price Ltd. Retrieved March 15, 2018 .

- ^ Ed Vasser: History Of The Climax Locomotive. End of an era. In: Climax Locomotives. Accessed March 10, 2018 .

- ^ Ed Vasser, Frankfort, Kentucky: History Of The Climax Locomotive. Climax Production. In: Climax Locomotives. Accessed March 10, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Patent US393896 : Proppeling gear for tram cars. Filed February 10, 1888 , published December 4, 1888 , inventor: George D. Gilbert.

- ^ A b Ed Vasser: History Of The Climax Locomotive. Climax Development. In: Climax Locomotives. Accessed March 11, 2018 (English).

- ↑ a b Patent US421894 : Tramway Locomotive. Published February 25, 1890 , inventor: Rush S.Battles.

- ↑ Patent US423720 : Tramway Locomotive. Published March 18, 1890 , inventor: Rush S.Battles.

- ↑ Patent US455154 : Locomotive (Horizontal Cylinder). Published June 30, 1891 , inventor: Rush S.Battles.

- ↑ Patent US504541 : Tramway Locomotive. Published September 5, 1893 , inventor: Charles D. Scott.

- ↑ The Climax Geared Steam Locomotive . In: American-Rails.com . ( american-rails.com [accessed March 4, 2018]).

- ^ A b Ed Vasser: History Of The Climax Locomotive. Historical Clarifications. In: Climax Locomotives. Accessed March 11, 2018 (English).

- ↑ a b Climax Geared Steam Locomotives. Variations. In: Geared Steam Locomotive Works. Accessed March 10, 2018 .

- ↑ Climax Components (Page 1). Tea. In: Geared Steam Locomotive Works. Accessed March 10, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Climax Locomotive S / N 1551 Restoration Project. Mountain State Railroad & Logging Historical Association, accessed March 16, 2018 .

- ^ John F. Campbell: Climax Notes. x28 - Phoenix Mine & Gratiot River RR. In: Geared Steam Locomotive Works. Retrieved March 17, 2018 .

- ^ Climax Locomotive . In: The Retreat at Artesian Lakes . ( artesianlakes.com [accessed March 17, 2018]).

- ↑ 15 tone Class A Climax - Keith Christensen Memorial . In: Tom's Toys . February 14, 2016 ( oldtomstoys.com [accessed March 16, 2018]).

- ^ Ed Vasser: Shop Number Search Results. S / N 399. (No longer available online.) Climax Locomotives, archived from the original on February 10, 2015 ; accessed on March 16, 2018 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Surviving Steam Locomotives in Alaska. Retrieved March 17, 2018 .

- ^ P. Curtis: The Tokomaru Steam Museum. List of exhibits. Retrieved March 15, 2018 (UK English).

- ^ A b Ed Vasser: Cabin Creek Lumber Class A Climax S / N 804. (No longer available online.) In: Climax Locomotives. Archived from the original on November 4, 2017 ; accessed on March 16, 2018 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ 48 ton Climax Rutledge Lumber Company. In: Steamlocomotive.com. Retrieved March 17, 2018 .

- ^ A b Brian McCamish: Abandoned Idaho Climax. Retrieved March 17, 2018 .

- ↑ Fruit Growers Supply (Sunkist) # 3. RailGiants Train Museum, accessed March 16, 2018 .

- ↑ Shawnigan Lake Lumber Co. No. 2. BC Forest Discovery Center, accessed March 16, 2018 (American English).

- ^ Ed Vasser: Shop Number Search Results. S / N 1059. (No longer available online.) In: Climax Locomotives. Archived from the original on May 18, 2017 ; accessed on March 16, 2018 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ David Maciulaitis: Climax Manufacturing Co. # 1,203 of 1913. In: rolling stock register. Retrieved March 16, 2018 .

- ↑ Climax. Shantytown Heritage Park, accessed March 15, 2018 .

- ↑ Roster. Moore Keppel and Company Climax No. 4. Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania. Retrieved March 17, 2018 (American English).

- ↑ David Maciulaitis: Climax Manufacturing Co. # 1317 of 1914. Rolling Stock Register, accessed March 16, 2018 .

- ↑ Punninator1: NC Cradle of Forestry's Climax # 3 !!! 6/13/13. October 15, 2013, accessed March 17, 2018 .

- ^ Hillcrest Lumber Co. No. 9. BC Forest Discovery Center, accessed March 16, 2018 (American English).

- ↑ Virtual Tour - Steam Train Ride . In: The White Mountain Central Railroad . July 19, 2013 ( whitemountaincentralrr.com [accessed March 16, 2018]).

- ↑ RootsOfMotivePower: 1922 Climax 2-truck steam locomotive walk around. September 15, 2010, accessed March 17, 2018 .

- ↑ Climax Locomotive Works Number 1650 Built 1924. The Glen Afton Line Heritage Railway, August 19, 2016, accessed March 15, 2018 .

- ^ Exhibit - Climax. Tasmanian Transport Museum, accessed March 15, 2018 .

- ↑ Climax Engine. Corry Area Historical Society, Inc. & Museum, accessed March 16, 2018 .

- ^ Roaring Camp Climax . In: Trainorders.com Discussion . ( trainorders.com [accessed March 17, 2018]).

- ↑ a b The Geared Locomotive Collection of Roaring Camp And Big Trees Narrow Gauge Railroad . In: The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (Ed.): 1988-8-21 . S. 5 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Climax did not assign the serial numbers after the deliveries. For example, No. 1692 was not delivered until December 1928, while No. 1694 was delivered in June.

- ^ Hillcrest Lumber Co. No. 10 . In: Locomotive Wiki . ( wikia.com [accessed March 16, 2018]).

- ^ Other Puffing Billy Locomotives. Climax. In: Puffing Billy Preservation Society. Accessed March 15, 2018 .

- ↑ Ed Vasser: Climax Shop Number 1505. (No longer available online.) Climax Locomotives, archived from the original on March 10, 2015 ; accessed on March 18, 2018 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Ferdinand - Character Profile & Bio . In: Thomas & Friends - Official Website . Retrieved August 26, 2017.