Dürer's self-portraits

|

| Thirteen-year-old self-portrait |

|---|

| Albrecht Dürer , 1484 |

| Silver pen on white primed paper |

| 27.5 x 19.6 cm |

| Albertina graphic collection |

The self-portraits of the painter and graphic artist Albrecht Dürer are among the most famous self-portraits in art history.

Thirteen-year-old self-portrait (I)

This drawing, made at the age of 13, is the oldest surviving self-portrait by Albrecht Dürer. He drew the picture with a silver pen , and this in the year in which he began an apprenticeship as a goldsmith in the workshop of his father Albrecht Dürer the Elder . He himself, however, already tended to become a painter at this time. The young Dürer presents himself in three-quarter profile with a cap and an outstretched index finger, which his gaze follows. The outstretched index finger can also be found in depictions of the apostle Johannes under the cross, as it is clearly depicted on the Isenheim altar by Matthias Grünewald .

Albrecht Dürer created this picture with a silver pen, a tool that does not allow any corrections. He learned the silver pen technique in his father's goldsmith's workshop.

The later inscription on this portrait reads:

- " Dz I have aws eim spigell after myself kunterfet In 1484 Jar Do I still have a kint wad. Dressing Dürir "

Thirteen-year-old self-portrait (II)

|

| Self-portrait of the boy |

|---|

| Albrecht Dürer , 1484 |

| Oil on paper |

| 26 × 17 cm |

Another portrait of a thirteen-year-old boy, which was formerly in the collections of the Pomeranian History Association in Stettin , has come down to us, presumably from the same year as the silver pen drawing in Vienna . It is an oil painting on paper, which shows the bust of a boy inclined slightly to the right. This bears the date 1484, which has not been interpreted with certainty, and the inscription below:

- im 13 iar what i

This picture was part of an account book of Duke Philip II of Pomerania and was published in 1927 by the curator of the collection at the time. In 1928 it was examined in detail by the Dürer researchers Hans and Erica Tietze . Due to the poor state of preservation, they did not want to decide whether it was an original work by the young Dürer or a copy based on a lost work. However, the similarity of the sitter to the Vienna silver pencil drawing was generally recognized. However, since the execution of the picture was described as very rough and not worthy of the young Dürer, the majority today assume that it is a copy, probably made around 1500 in Augsburg.

Self-Portrait with Eryngium

|

| Self-Portrait with Eryngium |

|---|

| Albrecht Dürer , 1493 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 57 × 45 cm |

| Musee du Louvre |

The self-portrait with eryngium is the earliest self-portrait painted by Dürer. The picture was preceded by two studies from 1491 and 1493. The first shows the young Dürer with his head propped up and a brooding look, while the second sketch shows a frontal view of a self-portrait and a study of his own hand with an invisible flower.

Self-Portrait with Cushions ( Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York)

Self-portrait with armband (Graphic Collection of the University Library Erlangen-Nürnberg )

This self-portrait documents Dürer's appearance at the age of 22. He painted it in Strasbourg during his wandering period before going back to Nuremberg and marrying Agnes Frey , the daughter of a very respected citizen, whom his father had chosen for him. The picture shows the young Dürer with the thistle-like plant Eryngium campestre (= lat. Man litter) in his right hand, which symbolizes the Passion of Christ and contains a reference to the crown of thorns. In the ' Hortus Sanitatis ' of 1485, however, the effect of an aphrodisiac is ascribed to this plant. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , who saw a copy of the picture in Helmstedt in 1805 , therefore considered it to be a courtship gift for Agnes Frey.

An inscription at the top of the picture under the year 1493 reads as follows:

- My sach the gat / when it shuts up

This inscription could be translated into modern German as follows:

- My things are determined from above.

This expresses Dürer's devotion to God, which is already indicated with the Eryngium.

What is striking is the “crooked” look, a feature of almost all of Dürer's self-portraits. The right pupil is in the outermost corner of the eye, while the left pupil looks straight ahead. This view can be explained by the fact that Dürer looked at himself from the side in the mirror.

Much has been puzzled over the meaning of the eryngium. In view of the fact that the Eryngium is popularly called "man loyal", it was related to the impending marriage with Agnes Frey, which was negotiated in his absence. It is also alleged that Dürer painted his self-portrait on parchment in order to be able to send it to his fiancée more easily. However, this assumption contradicts the inscription: "My sach die gat / As es above schtat". This expression of trust in God is difficult to see in the context of courtship. Dürer probably made the painting for himself like his other self-portraits.

Self-portrait with landscape (Madrid self-portrait)

|

| Self-portrait with landscape |

|---|

| Albrecht Dürer , 1498 |

| oil |

| 52 × 40 cm |

| Museo del Prado |

The self-portrait with landscape shows Dürer in the clothes of an elegant patrician , not in the work clothes of an artisan. The inscription on the right edge of the picture reads as follows:

1498. I paint that according to my shape. I was 26 years old.

Below is Dürer's monogram with the initials AD , which appears in almost all of his works.

The hat corresponds to the latest fashion of its time and the garment with the fine embroidery on the hem was also elegant, because Dürer was fashion-conscious and proud. The careful execution of the locks of hair, which appear to be engraved in gold, testifies to his apprenticeship in the goldsmith's workshop of his father.

On his way to Venice Dürer crossed the Alps , where he was so impressed by the mountain landscape that he captured it in drawings and later used it to create backgrounds.

The relaxed position with the arm on a ledge and the slightly turned head as well as the window in the background shows that Dürer has adopted the latest approaches to Venetian portrait art. On the other hand, the refusal to idealize his face refers to the northern traditions of his German homeland.

In Germany, in Dürer's time - unlike in Italy, for example - artists were still viewed as craftsmen. Dürer presents himself here as an aristocratic, proud young man with ringlets, who shows serenity. Sr. Wendy Becket says:

His fashionable, lavish clothing, as well as the dramatic mountain landscape that one sees through the window (and which is intended to indicate his broader horizon), reveals that he considered himself anything but a narrow-minded provincial.

In Kindler's Malereilexikon it says about this self-portrait:

It seems that this splendid Madrid self-portrait earned him a whole series of commissions; for in the next few years similar, but simpler portraits were created, especially of the Tucher family in 1499, which, in their energetic modeling, say a lot about the new class consciousness of this rich bourgeoisie.

The picture came into the possession of King Charles I of England, who received it as a gift from Lord Arundel . Lord Arundel, in turn, had received it as a gift from the Nuremberg city council.

After the execution of King Charles in 1649, the Spanish ambassador Alonso de Cárdenas bought the portrait on secret order from King Philip IV , which brought it to Spain and ultimately to the Prado .

Self-portrait in a fur skirt (Munich self-portrait)

|

| Self-portrait in a fur skirt |

|---|

| Albrecht Dürer , 1500 |

| oil on wood |

| 67 × 49 cm |

| Old Pinakothek |

The self-portrait in a fur skirt is in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich.

The picture shows Dürer in clothes in a hierarchical pose, which until then was reserved for kings and Christ . For Dürer this was possibly an interpretation of the doctrine of the Imitatio Christi and a proof of his belief in the artist as the creator of God ( Divino artista ).

The right hand lies on the fur strip with a strange finger position, while the left is not shown at all. It is the only self-portrait by Dürer that does not show the painting's hand.

In contrast to other self-portraits, Dürer did not choose the three-quarter view here, but the frontal view. This created a symmetrical portrait. However, it is not clear whether Dürer painted his reflection on the linden wood picture support or whether he confronts the viewer with a natural perspective. In the mirror image, Dürer's visible hand would be his left, but in the other case his right, the painter's hand. Dürer's self-portrait , which he drew with silver pen in 1484 at the age of 13 or 14 and later issued as a mirror image in inscriptions, speaks in favor of the mirror image thesis (Vienna, Graphic Collection, Albertina). In this early self-portrait, too, Dürer's rights are ostentatiously hidden. In addition, Christoph Scheurl gave a speech on the fame of the arts in 1508, in which he mentioned Dürer in detail. Using ancient Lobestopoi, he mentions an unspecified self-portrait by Dürer, which Dürer painted from a mirror. He embellished the statement with the learned reference to the ancient painter Marcia, who was written by Pliny the Elder. Ä. in the 35th book of the "Naturalis Historiae" was still called Iaia from Kyzikos and was named by Boccaccio between 1360 and 1362 in his book "De claris mulieribus" Marcia, to which Scheurl referred.

There are two inscriptions at eye level: at the top left the monogram with the initials AD , which appears in almost all of his works, and the year 1500 .

A four-line Latin inscription at the top right of the picture reads as follows:

- Albertus Durerus Noricus / ipsum me propriis sic effin / gebam coloribus aetatis / anno XXVIII

In the German translation this means:

So I, Albrecht Dürer from Nuremberg, painted myself in natural colors at the age of 28.

It is likely that this caption was added later. It is in a cartridge that has the shape of a butterfly and is difficult to see. In Kindler's Malereilexikon it says about this self-portrait:

The famous Munich self-portrait from 1500, which is fundamentally different in every respect, is of great importance for the entire work of the master.

For a long time in the history of art the importance of fur in Dürer's self-portrait in Munich was ignored. This is all the more astonishing as Dürer reaches very clearly with his visible hand into the collar fur, as if he did not want to draw the viewer's attention to the texture of his fur without pride. Dürer's outerwear is a long-sleeved type of coat that was called Schaube or fur hood around 1500 . This was buttoned at the front in the middle and had a wide V-neckline in the chest area, which was provided with a wide collar. Depending on the stand, the screw-bearer could decorate the collar in different ways and decorate it with furs. A special feature of Dürer's Schaube are the horizontally slit sleeves on the upper arms, where they seem interrupted and reveal the white undergarment. In the diagrams around 1500 this type seems to be an exception in the fine arts.

Much more important, however, is the most important attribute in Dürer's self-portrait, the Schaube, the dense fur trim on the collar, which is laid over the chest in a V-shape in hand-wide strips. Each individual hair is applied with a fine brushstroke and differentiated in its coloring and lighting from the tip to the lower shaft in different shades of brown. In the dimly subdued illumination of the diffuse image space, the fur stands out in rich contrast from the somewhat lighter brown of the rest of the coat material. The effort with which Dürer took care of his depiction, and his hand, whose delicate fingers point to it as well as carefully reaching into it, are important indications that give the depicted item of clothing and, above all, the corresponding fur a high level of importance. The type of fur was particularly important for the men around 1500, who were given exact instructions depending on the status. The reference work for the cross-empire dress codes is the Reichspolizeiordnung of 1530. It represents the binding conclusion of 35 years of legislative development, which has constitutional qualities, and declares the marten fur as the most important insignia of the Schaube.

The dress code of the time stipulated that the marten fur was reserved only for the urban elites in Germany. They had to be rich, belong to the nobility or patriciate and thus be able to advise, i.e., due to their high social status, have the opportunity to be elected to the city council (government of the city). Dürer did not meet both conditions around 1500. At that time he was neither rich, nor was he advisable, because as a painter he was one of those craftsmen who had not even been upgraded by a guild. It cannot therefore be ruled out that the date and signature on the self-portrait is a subsequent forgery. And due to Dürer's marten fur, it cannot be ruled out that he did not paint his self-portrait until 1509, when he was finally able to advise and even elected to the Nuremberg Grand Council.

If you consider the historical significance of the marten fur in the picture, then Dürer's self-portrait in Munich assumes a significance that has hitherto been neglected. Because by presenting himself for the first time among the artist self-portraits with the insignia of social elites, he is not only raising his own image. He also ennobled painting. In addition to his artistic vocation, Dürer is probably also interested in making a political statement in his unusual self-portrait. Because he is to be seen as a councilor, he refers to his official reference to the judiciary. In numerous pictorial sources of the time ( Holbein the Younger , Grien , Cranach the Elder , Breu the Elder , etc.) the fur hood is clearly used as a judge's insignia.

Dürer also seems to understand them that way. And through his emphatic resemblance to Christ ( imitatio Christi ) Dürer appears like a judge of the world. This connection can only be understood if one keeps in mind that Dürer was extremely dissatisfied with the legal situation of his time, which was caused by the slow progress of the reform of the imperial law. Medieval customary law was replaced by written canon law based on the Justinian model. Although the legal codification and its learned judiciary ultimately improved and objectified justice from which we still benefit today, the road to get there was rocky, and not only Dürer experienced the change as a threatening legal uncertainty.

The legal term was not only related to the jurisdiction. Rather, it is also used in the art of the Renaissance, because at that time art was understood as the power of judgment about the interpretation of the world. In art theory it is above all the concept of the giudizio dell'occhio , the judgment of the artist's eye, which has to judge measure, number and proportion in order to create beauty. Il giudizio dell'occhio means the sense of proportion that is given by God. And only with this sense of proportion it is possible to grasp the entire visible world order ( Marsilio Ficino ). Giorgio Vasari later even used the term giudizio universale in this context . As is well known, Italian art theory had some influence on Dürer's views of art. For him, the artist's research on proportions was the foundation of his free creative work from the spirit.

Dürer emphasizes that the artist acquires a sense of proportion , which corresponds to the Italian giudizio dell'occhio , by practicing on nature. Only the extensive measurement of nature and its objects enables the acquisition of a sense of proportion, which is a prerequisite for recognizing beauty. And it is remarkable that Dürer makes the definition of beauty dependent on the artist's judgment. Dürer compares his judgment of beauty with the act of law-making; In his drafts (1512) for the introduction to his painting textbook , Dürer wrote:

“To be called 'beautiful', I want to put here how some are 'right': in other words, what all the world values are right, we consider right. So what all the world considers beautiful, we want to consider beautiful too, and strive to do it. "

Here, beauty is seen as part of the God-given natural law, which is based on the relationships of measure, number and weight. For Dürer, the world order is embedded within the co-ordinates of legal norms and the law of proportion, which through the artist - in the Platonic sense - gets its real visibility. Dürer understands the divine order of values as a holistic fact into which the measure in the sense of proportion is inscribed as well as the measure in the sense of human behavior. The divine measure is therefore also to be understood morally, which is why hubris is to be equated with presumption. The measure of the number and the measure of action are united and through their proportional perfection of form in a mathematical and moral sense they restore the measured balance. For Dürer, the perfection of art lies in the moderation of numbers and morals.

While Dürer did his doctorate in the Munich self-portrait on the one hand and illustrated himself as a member of the social city elite by means of the fur hood, the painting with Dürer's Christ-like resemblance alludes to Justitia, the highest ruling virtue, which in turn is due to the legal connotation of the Schaube with the fur of the back marten receives its symbolic counterpart. But the iconology of the painting receives the highest consecration through its clear art-theoretical reference.

Dürer sees the points of contact between art and justice in the measure and proportion of the world order. The universal claim of the picture statement is based on the clear resemblance to the icon of Christ. In it merge - for this interpretation the symbolism of the marten pigeon is essential - the artist as creator god and the eschatological concept of judge.

The self-portrait in the fur skirt was probably not intended for sale. Its original function is in the dark, because written sources about the self-portrait are only available from 1577, when Karel van Mander wanted to see the picture in the Nuremberg town hall. In 1805 it was acquired by the Central Painting Gallery of the Munich Pinakothek , where it remained for the past two centuries.

From December 1800 to March 1801, the imperial city of Nuremberg was again occupied by French troops. During this second occupation, the art commissioner François-Marie Neveu, sent from Paris, stayed in Nuremberg from the end of January to the beginning of March 1801 to confiscate art treasures in order to complete the Louvre in Paris, which was under construction .

The French commissioner François-Marie Neveu also requisitioned a painting based on the self-portrait by Albrecht Dürer from 1500. He did not notice that it was not the original and sent it with other pictures, manuscripts and incunabula of considerable value the municipal property in the Louvre in Paris. The original had been secretly exchanged for a Dürer reproduction by an unknown painter from the art trade by Abraham Wolfgang Küfner . This resistance action against the French occupation took place in cooperation with the council consul of the imperial city of Nuremberg Georg Gustav Petz von Lichtenhof , as can be seen in 1805.

On July 15, 1805, Georg Gustav Petz von Lichtenhof and the art dealer Abraham Wolfgang Küfner sent a letter of offer to the electoral gallery in Munich to purchase the "Self-Portrait from 1500 by Albrecht Dürer" for 600 guilders. The copy of the original offer letter is now in the archive of the Bavarian State Painting Collections . The general director Johann Christian von Mannlich bought the original Dürer self-portrait. As a result, Albrecht Dürer's self-portrait is now in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. It was also not awarded to Nuremberg for the 2012 anniversary show, which sparked heated controversy in the media.

The original of the Dürer self-portrait had already been owned by Georg Gustav Petz von Lichtenhof for 20 years , who had acquired it in 1785 at an estate auction of JG Friedrich von Hagen, the owner of Oberbürg Castle in the Nuremberg suburb of Laufamholz. Abraham Wolfgang Küfner was the art expert when it was sold to Munich in 1805. With the sale, the “evidence” for the life-threatening exchange with a reproduction in 1801 was “removed” and the danger of punishment by the French was averted.

Through this regular sale, the original Dürer self-portrait got from Nuremberg to Munich. Today only reproductions of Albrecht Dürer's paintings can be seen in Dürer's House in Nuremberg.

The painting formed the motif for the largest puzzle in the world in terms of surface area. With more than 300 m² and over 1700 parts, the work was puzzled over two days.

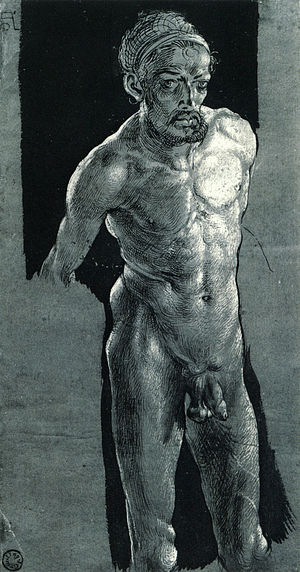

Self-portrait as a nude

|

| Self-portrait as a nude |

|---|

| Albrecht Dürer , 1500 to 1512 |

| Drawing in pen and brush on green primed paper, heightened with white |

| 29.2 x 15.4 cm |

| Weimar City Palace |

The self-portrait as a nude or even just a nude study shows Albrecht Dürer without clothes. This is a standing portrait, with the area below the knees and the right arm from the elbow missing and only part of the upper arm of the left arm visible.

Dürer's studies of the human figure were often limited to the portrait and individual body parts and did not always encompass the entire figure. The figure is bent slightly forward, presumably because Dürer used a small mirror. Dürer presents himself in a relaxed posture without false shame. The fold of skin over the right hip is reminiscent of Christ's wound on the side . In addition, like Christ, Dürer stands on the pillar of the scourge. However, Dürer portrays himself naked, while he always covers Christ with a loincloth and also always covers Adam and Eve's nakedness with a branch. This picture is Dürer's most intimate self-portrait.

The drawn part of the body has a dark background. The person depicted looks directly at the viewer. Dürer's name mark is shown in the upper left corner, but was not attached by Dürer himself. In the lower left corner there is now a stamp that identifies the picture as part of the Grünling Collection . It was made using an unusual mixed technique of pen, brush and chalk.

The exact time of the creation of the drawing is unknown and dating is quite difficult. Science is certain that the picture must have been created sometime between 1500 and 1512, since Dürer used the combination technique used here relatively often at that time. According to Friedrich Winkler , the depicted Dürer is significantly older than 29 years and younger than 41, so that he would locate the work almost exactly in the middle of the specified period.

Very little is known about the history of the picture. Dürer himself did not give it up during his lifetime.

One knows from the stamp that it was in the Grünling Collection before it went to the current owner, the Castle Museum in Weimar. Since the Grünling collection came to a not insignificant part from the holdings of the Albertina in Vienna , the previous owner is assumed to be here.

Self-portrait for Raffael

The existence of this picture is documented by Giorgio Vasari in his biography of Raphael . This was in return for the nude studies donated by Raphael to Dürer about the battle of Ostia . According to Vasari's description, it was a watercolor painting on a so-called handkerchief , which, since Dürer had omitted all the lights in the picture, could be viewed from both the front and the back. At that time it was in the collection of the painter Giulio Romano , who had inherited it from Raphael. Later, after Joachim von Sandrart , it became the property of the Princely Collection of Mantua .

The exact appearance of this image, lost today, is unknown. Hugo Kehrer suspected that Raphael copied it in his expulsion of Heliodorus by giving the front litter bearer the features of Dürer. This shows almost the same head posture as Dürer in his self-portrait with eryngium and self-portrait with landscape . Haircut, German fashion and beard shape point to a period from 1514. According to Vasari, however, the sitter is Marco Antoni Raimondi .

More self-portraits

Landau altar

In addition to the self-portraits listed here, Dürer has included self-portraits of himself in various pictures, for example on the All Saints' Day picture ( Landau Altar ), where he has depicted himself on the lower right with a tablet. The following Latin inscription is written on the tablet:

Albertus Durer Noricus faciebat anno a Virginis partu 1511.

(German: Albrecht Dürer from Nuremberg created it in 1511 after the virgin birth. )

The feast of the Rosary

At the Rosary Festival, Dürer appears on the right edge of the picture. He is holding a piece of paper with the Latin inscription:

Exegit quinque mestri / spatio Albertus / Durer Germanus MDVI / AD

With this note Dürer indicates that he created the painting in just five months in 1506 (MDVI).

The Feast of the Rosary : Dürer on the right edge

Torture of the ten thousand Christians

In the torture of the ten thousand Christians , Dürer is in the center of the picture, not involved in what is happening around him. Here Dürer is accompanied by an older man whose identity has not been clarified. It is believed that it could be the humanist and poet Conrad Celtis . The two contemplate what is happening.

Torture of the ten thousand Christians (Dürer in the center of the picture)

Dürer and Conrad Celtis

Heller altar

Almost simultaneously with the "Ten Thousand Martyrs", Dürer received the major order for the so-called Heller Altar for the Frankfurt cloth merchant and mayor Jakob Heller . Albrecht Dürer stands in the background, leaning slightly against a board with his signature and the following Latin inscription:

Albertus Durer Alemanus faciebat post Virginis partum 1509.

(German: The German Albrecht Dürer created it in 1509 after the virgin birth. )

Heller altar : Dürer in the middle of the central panel

Others

On his trip to Holland, Dürer contracted an illness that caused the spleen to enlarge . Dürer pointed this out to his doctor with a sketch in the letter, showing himself how he points to his enlarged spleen, and writes:

- " Do the yellow spot is vnd with the finger drawff dewt do me white. "

- (It hurts where the yellow spot is and what I point with my finger.)

On the outside of the Jabacher Altar, Dürer depicts himself as a drummer next to a flute player.

Individual evidence

- ^ F. Henry, In: monthly sheets of the society for Pomeranian history and antiquity 41, 1927, p. 95 f.

- ↑ Fedja Anzelewsky, Albrecht Dürer. The painterly work. New edition. Textband, Vol. 1, p. 117.

- ↑ Jeroen Stumpel and Jolein van Kregten . 2002, JSTOR : 889419 .

- ↑ Gerd Unverfetern (Ed.): Dürer's things . Art collection of the University of Göttingen, 1997, p. 88 .

- ↑ Beckett: " The History of Painting "

- ↑ Kindler's Painting Lexicon, p. 2544

- ^ Art website with its own section on the acquisition of paintings by Ambassador Alonso de Cárdenas

- ↑ See Eberlein, Johann Konrad: Albrecht Dürer. Hamburg (2nd edition) 2006, p. 55

- ↑ Kindler's Painting Lexicon, p. 2544

- ↑ Bulst, Neithard / Lüttenberg, Thomas / Priever, Andreas: Image or ideal? Portraits of Christoph Amberger in the field of tension between legal norms and social demands. In: Saeculum, 53, 2002, pp. 21–73, here p. 33.

- ↑ Grote, Ludwig: From craftsman to artist. In: Festschrift for Hans Liermann on his 70th birthday. Erlangen 1964, pp. 26-47.

- ↑ On this Zitzlsperger, Philipp: Dürer's fur and the right in the picture - clothing science as a method of art history. Berlin 2008, pp. 63-76.

- ^ Zitzlsperger, Philipp: Dürer's fur and the right in the picture - clothing science as a method of art history. Berlin 2008, pp. 85-99.

- ↑ On this Scheil, Elfride: Albrecht Dürer's Melancolia § I and justice. In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 70, 2007, pp. 201–214, here p. 202.

- ^ Zitzlsperger, Philipp: Dürer's fur and the right in the picture - clothing science as a method of art history. Berlin 2008, pp. 100–117. ISBN 978-3-05-004522-1 .

- ↑ For the history of the picture before it was acquired in 1805, cf. Goldberg, Gisela / Heimberg, Bruno / Schawe. Martin: Albrecht Dürer. The paintings of the Alte Pinakothek. Edited by the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen. Munich 1998, pp. 340–342.

- ↑ Hans Recknagel, Altnürnberger Landschaft e. V., French occupations of Nuremberg 1796–1806. Lecture on March 25, 2006

- ↑ Prof. Dr. Bénédicte Savoy: KUNSTRAUB, Napoleon's confiscations in Germany and the European consequences.

- ↑ Hans Recknagel, Altnürnberger Landschaft e. V., French occupations of Nuremberg 1796–1806. Lecture on March 25, 2006

- ↑ Helmut Eichler, Munich: »Not stolen! Documentation 06.2015 «, page 7

- ↑ BStGS, Archiv Fach IX, lit. A, no. 1, convolute 1

- ^ Albrecht Dürer: Largest Dürer exhibition for 40 years in the Nuremberg National Museum. In: Focus Online. May 23, 2012, accessed June 14, 2019 .

- ^ Ansgar Wittek: 'Laufamholz, Herrensitz', 1984 edition, page 82: The Oberbürg in changing ownership

- ↑ Helmut Eichler, Munich: »Not stolen! Documentation 06.2015 «, page 6

- ↑ Dürersaal in the Dürerhaus Nuremberg ( Memento of the original from October 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ The Greatest Puzzle in the World , The History of the Puzzle.

- ↑ Fedja Anzelewsky, Albrecht Dürer. The painterly work. New edition. Textband, vol. 1, p. 229 f.

literature

- Pierre Vaisse / Angela Ottino Della Chiesa: The painted work of Albrecht Dürer , in: Classics of Art , Kunstkreis Luzern, 1968

- Fedja Anzelewsky : Albrecht Dürer. The painterly work . New edition, two volumes, Berlin: Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, 1991 ISBN 3-87157-137-7

- Robert Cumming: On the trail of great masters . Cologne: DuMont, 1998. ISBN 3-7701-4633-6

- Johann Konrad Eberlein: Albrecht Dürer . Reinbek: Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, 2003. ISBN 3-499-50598-3

- Thomas Eser: Dürer's self-portraits as “test pieces”. A pragmatic interpretation in: Images of people. Contributions to Old German Art , ed. by Andreas Tacke and Stefan Heinz, Petersberg 2011, pp. 159–176. ISBN 3-86568-622-2

- Anja Grebe: Albrecht Dürer. Artist, work and time . Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2006. ISBN 978-3-534-18788-1

- Gabriele Kopp-Schmidt: "With the colors of Apelles". Antique artist praise in Dürer's self-portrait from 1500 , in: Wolfenbütteler Renaissance-Mitteilungen 28, 2004, pp. 1–24.

- Thomas Schauerte: Dürer. The distant genius. A biography , Stuttgart: Reclam, 2012. ISBN 978-3-15-010856-7

- Sebastian Schmidt: “Then you made the excellent artist rich”. On the original definition of Albrecht Dürer's self-portrait in a fur skirt , in: Anzeiger des Germanisches Nationalmuseums 2010, pp. 65–82.

- Friedrich Winkler: The drawings of Albrecht Dürer. Volume I: 1484-1502. Deutscher Verein für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 1936, pp. 186 to 187 and plate 267

- Dieter Wuttke: Unknown Celtis epigrams to the praise of Dürer , in: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 30, 1967, pp. 321-325.

- Reinhard Liess : The self-portrait of the thirteen-year-old Dürer , in: Art and Art Education. Contributions to art education, art history and aesthetics. Festschrift for Ernst Straßner , Göttingen 1975, pp. 77–100.

- Philipp Zitzlsperger: Dürer's fur and the right in the picture - clothing science as a method of art history , Berlin 2008. ISBN 978-3-05-004522-1