Three-toed woodpecker

| Three-toed woodpecker | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

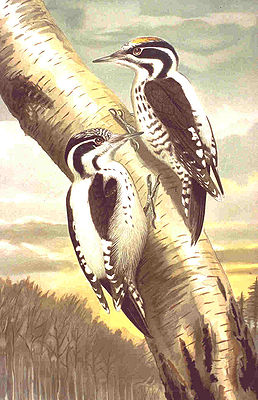

Three- toed woodpecker ( Picoides tridactylus ), left female, right male |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Picoides tridactylus | ||||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

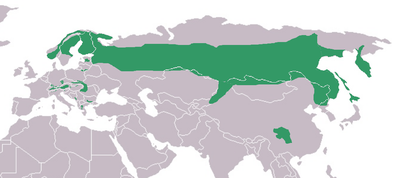

The three- toed woodpecker ( Picoides tridactylus ) is one of the twelve species of the genus Picoides within the subfamily of the real woodpeckers . The species, which is mostly differentiated into 8 subspecies, is represented in the boreal Palearctic . The nearctic representatives, which were previously part of the species Picoides tridactylus , are now regarded as an independent species of spruce woodpecker ( Picoides dorsalis ). The northern European occurrences of Picoides tridactylus belong to the nominate form , while the central and southeastern European relic occurrences belong to the subspecies P. t. alpinus .

The three-toed woodpecker is slightly smaller than a great spotted woodpecker and, due to the lack of any red in the plumage, can be easily identified. It lives in old coniferous forests rich in dead wood, where it feeds mainly on wood-dwelling beetle larvae. In Central and Southeastern Europe, its occurrence is limited to montane or subalpine locations. It does not appear to be common anywhere in its entire range, but is considered safe according to the IUCN.

Appearance

The plumage of the almost variegated woodpecker (body length 20 to 22 centimeters) has no red or pink tones. Despite the very different distribution of black and white plumage between the breeds, three-toed woodpeckers appear rather dark. Characteristic are the dark cheeks and the light, yellowish beard and the white stripes above the eyes. The over-eye stripe runs in a V-shape into the neck, where it joins the white to white-piebald back in the lighter boreal subspecies, and ends in the black upper back in some East Asian and the native alpinus subspecies . The abdominal plumage is black and white sparrowed in most of the subspecies , but in some East Asian subspecies it is also dark, almost without any drawing. The feather feathers of the wings are black, without white shoulder marks, the wings of the hand have black and white banding, as are the outer control feathers. The yellow to orange-yellow apex of the male is not always clearly visible. In the slightly more dull female, the vertex is black-gray and looks a bit frosted. The sexes do not differ in size. All in all, the species can be easily determined by field ornithology. The dark cheekfield and the lack of reds and white shoulder markings are the best distinguishing features.

In most climbing woodpeckers, the largely functionless toe, which is directed backwards, is outwardly completely receded in this species. When climbing normally up or down, two toes are forward and one is backward. In spiral climbing - which is particularly common with this species - the three toes are roughly at right angles to each other.

voice

The three-toed woodpecker is much less audible than the great spotted woodpecker. Overall, the vocalizations (except for the drumming) are also quieter and more muffled than this one. The most frequent call is a subdued, colored woodpecker-like Güg or Gügg , sometimes harder Kük . When scolding (slower than the great spotted woodpecker), several elements are usually strung together in a slightly sloping tone row. In addition, the species has a number of trilling and chuckling vocalizations.

The drumming , which is practiced by both sexes, differs quite well from that of the great spotted woodpecker, but is very similar to that of the white-backed woodpecker . The individual vertebrae are very long (on average about 1.3 seconds for 20 beats), with the frequency of the last 5 beats being significantly accelerated. In addition to the much shorter duration of the drum roll, this acceleration of the frequency is a good distinguishing feature from the white-backed woodpecker. Mated woodpeckers communicate with slow drum rolls.

Young and Adult, Feeding.

distribution

The three-toed woodpecker is common in the boreal forest throughout the Palearctic . He inhabits the entire northern belt of coniferous forests from northeast Poland, the Baltic States and central Scandinavia eastwards to Kamchatka , Sakhalin and Hokkaidō . It is isolated from the closed distribution area in western China, especially in Tianshan , as well as in some mountain regions in Europe.

The Central European and Southeastern European distribution areas, which are regarded as relict occurrences in the Ice Age, include subalpine to alpine locations in the Alps, the Carpathians , the Dinaric Mountains and the Rhodope Mountains . There is also suspicion of breeding in some mountainous areas in Greece.

Systematics

The transitions between the different subspecies are clinical, mixed forms are common in the contact zones. Overall, the classification of the subspecies of the three-toed woodpecker is not very simple, as there are considerable individual differences in the core areas of the distribution of a subspecies.

- Subspecies of the northern Palearctic : Mostly very strong beak, (almost) unpainted white lower back, relatively low-contrast and lighter side markings. The subspecies become lighter from west to northeast, P. t. albidor has an almost unmarked white belly. Towards the southeast, however, the plumage becomes significantly darker again.

- P. t. tridactylus : The nominate form from Scandinavia to Ussuri .

- P. t. crissoleucus : Northern taiga from the Urals eastwards to the northern Amur region .

- P. t. albidor : Isolated occurrences on southern Kamchatka and some neighboring islands; this subspecies possibly also colonizes the northernmost Japanese islands.

- Southeast and South Palearctic subspecies, as well as P. t. alpinus . These birds are slightly smaller than the boreal subspecies and overall darker. The black and white distribution varies.

- P. t. alpinus and P. t. tienschanicus: Despite the large spreading distance, only small differences in color - see description above.

- P. t. funebris: This small subspecies from western China only shows sparse white drawings. The remaining Southeast Asian subspecies are also smaller and darker than the boreal ones, but not as extremely dark in color as P. t. funebris

- 3rd photo - selection field below right: funebris - females;

The three North American subspecies of the spruce woodpecker ( P. dorsalis dorsalis , P. d. Bacatus and P. d. Fasciatus ) were also previously considered subspecies of the three- toed woodpecker . In a molecular genetic investigation of the mitochondrial DNA , however, it was found that the Eurasian and North American subspecies each form clearly demarcated monophyletic groups and that the genetic distance is sufficiently large to give both groups species status. The North American subspecies were therefore separated from the three- toed woodpecker as a separate species, Picoides dorsalis .

Distribution in Central Europe

The subspecies P. t. alpinus is a rare breeding bird in Central European coniferous forests of the submontane and montane (to subalpine) level. The focus of occurrence in Austria is in Styria (especially in the Niedere Tauern and in the Hochschwab area ) and in Vorarlberg , here especially in the Bregenz Forest and the Montafon . The German breeding areas are concentrated in the Black Forest, in the Württemberg and Bavarian Allgäu , in the Berchtesgaden National Park and in the Bavarian Forest National Park . In Switzerland, too, the species is only a local breeding bird whose occurrence is limited to favorable locations within the main Alpine ridge . Brood occurrences in the Swiss Jura have also been known since the 1990s, but their stability cannot yet be foreseen.

There are other good and stable deposits in the Czech Republic and Slovakia; In these areas of distribution, the three-toed woodpeckers breeding north of the High Tatras and north of the Beskids are already predominantly in the nominate form. In Slovenia and Croatia, as well as in the far north of Italy , the species should also breed regularly, albeit in small numbers. Even in the high altitudes of northern and especially northeastern Hungary ( Geschrittenstein , Matra Mountains ), P. t. alpinus very occasionally to the breeding bird fauna.

Vertically, the occurrences in the entire Central European description area are limited to altitudes between 700 and 2000 meters, with the lowest nesting locations in the southern Black Forest and in western Lower Austria being around 600 meters above sea level. The highest evidence of breeding was found in the southern Limestone Alps near 2000 meters above sea level.

habitat

The three- toed woodpecker is very closely tied to the spruce, but also breeds, albeit in lower densities, in the pine forest taiga or in larch and stone pine stands . In the northern taiga it also occurs in pure birch stands.

P. t. alpinus breeds almost exclusively in pure spruce stands, it is only occasionally found in old pure stands of common pine ( Pinus sylvestris ) and Macedonian pine ( Pinus peuce ). Less managed forests with large islands of light and a large proportion of dead or damaged wood form ideal habitats . In the lowlands, moist, boggy forest areas are clearly preferred to dry ones, in the subalpine locations of Central and Southern Europe it is primarily autochthonous spruce forests that offer ideal habitats for the species.

food

The three-toed woodpecker feeds mainly on insects, which it captures by chopping or poking from the bark, mostly dead trees or at least trees that are severely impaired in their vitality. Larvae, pupae and immature adults of bark beetles , weevils , jewel beetles , longhorn beetles as well as wood wasps and willow borer play the largest role in the food spectrum of the species.

The three-toed woodpecker only consumes vegetable food to a small extent. Spruce seeds may be consumed regularly when there is a shortage of food or as a supplement.

However , like other great spotted woodpeckers, ringing is also important for this species to acquire food. It is likely that tree saps (and tree resins) are even used in rearing boys.

behavior

The three-toed woodpecker is a pronounced chopping and climbing woodpecker. The period of activity begins with sunrise and ends with sunset; extremely bad weather can shorten this period somewhat.

The three-toed woodpecker resembles the great spotted woodpecker ( Dendrocopos major ) in its movements . But with him the spiral hopping up and sliding down the trunk seem particularly easy and playful. This woodpecker can only be seen very rarely on the ground or on lying trunks. There it moves by hopping on two legs.

The flight is a powerful arc flight; in the fall phase, the wings are placed close to the body. Clear wing noises can be heard during sudden turns.

The woodpecker spends rest and cleaning phases during the day (usually around noon) hanging from a trunk. In most cases, however, he visits a woodpecker cave to sleep. In terms of enemy and aggressive behavior, the species is also very similar to the great spotted woodpecker, but it seems to be a bit more tolerable. Three-toed woodpeckers are relatively little shy. Often times they let people get within 5 meters of them before fleeing. Most of the time they then move away inconspicuously, without the usual scolding or cackling.

Three-toed woodpeckers that do not leave their breeding territory during the winter months also show territorial behavior outside of the breeding season. Here, males and females often share their ancestral breeding ground, with significantly reduced aggressive behavior between the partners. Usually, however, the female is pushed into the suboptimal areas.

hikes

Most three-toed woodpeckers are resident birds that stay in the breeding area even at low temperatures. Some populations (especially those of the Central and East Asian subspecies) appear to be line birds or partial migrants . This should also apply to the nearctic subspecies, at least the northernmost breeding sites are cleared in the winter months. Occasionally there are eruptive migrations of entire populations, which can take on the character of an evasion .

The young birds dismigrieren after the very long lead time and obviously strong family bond usually only in the surrounding area, but nestberingte young birds were recovered in relatively wide area from the breeding site.

Breeding biology

Three-toed woodpeckers become sexually mature towards the end of their first year of life; they lead a monogamous breeding season marriage. The partner bond seems to be quite strong even outside the breeding season, regardless of the availability of an alternative partner. Reparations over several years have been observed. In such cases, a loose cohesion does not completely disappear even during the winter months. Courtship and hunting grounds can begin in mid-winter and end between the beginning of April and the end of May, depending on the altitude and the weather. Overall, three-toed woodpeckers are not particularly noticeable during this time (apart from long and persistent drumming).

Three-toed woodpeckers create new breeding holes every year, which the male alone chisels into dead or dying conifers, mostly spruce trees. Nesting holes from the previous year or those of other woodpeckers are rarely used.

The three to five pure white, pointed oval eggs are placed on the cave floor, which has only been loosened by wood chips, and incubated for about 12 days with regular detachment. It can take up to 25 days for the nestlings, who are provided with food and care by both parents, to leave the brood cavity; This is followed by a remarkably long lead time, which can last over a month and during which the young are fed regularly at the beginning, but only occasionally later.

Three-toed woodpeckers usually breed once a year; second broods only occur regularly when the clutch is lost.

Inventory and inventory trends

IUCN estimates the total population very roughly at 5-50 million individuals within a distribution area of approximately 15 million square kilometers. Across Europe, the holdings are rated D (= depleted / thinned out) (mainly because of the decline in the nominate form) . In Switzerland, Poland and the Czech Republic, the species is listed in the national red lists of breeding birds. For many, especially the Southeast Asian subspecies, no precise information on population development is available. Also from the main distribution areas in Siberia there are neither population figures nor population estimates.

The European stocks must be assessed very differently. The population densities of the nominate form in Scandinavia have steadily thinned out since the 1970s, but so far no area losses have occurred. The main reasons for this are the intensification of forestry and the creation of monotonous age-class forests, as a result of which old stands rich in dead wood are increasingly disappearing. Rigorous forest hygiene measures after intensive bark beetle infestation also reduce the quality of the habitat of this species. In the other north-eastern European countries, populations appear to be stable , and an increase has even been reported in Estonia . The species can briefly benefit from storm events and bark beetle gradations and is then able to expand its breeding areas.

The subspecies P. t. alpinus seems to have expanded its breeding area in recent decades. Perhaps these repopulations of long-abandoned breeding areas can also be traced back to more detailed searches in the various mapping campaigns .

supporting documents

Individual evidence

- ↑ data sheet BirdLife international (engl.)

- ^ Robert M. Zink, Sievert Rohwer, Sergei Drovetski, Rachelle C. Blackwell-Rago and Shannon L. Farrell: Holarctic Phylogeography and Species Limits of Three-Toed Woodpeckers. Condor 104, 2002: pp. 167-170

- ↑ The spruce woodpecker at Avibase

- ↑ Datasheet BirdsInEurope pdf engl.

- ↑ Bauer & Berthold (1997) p. 295

- ↑ Christoph Grüneberg, Hans-Günther Bauer, Heiko Haupt, Ommo Hüppop, Torsten Ryslavy & Peter Südbeck: Red List of Germany's Breeding Birds , 5th version, November 30, 2015 . In: Reports on bird protection . tape 52 , 2015, p. 19-67 .

literature

- Hans-Günther Bauer & Peter Berthold : The breeding birds of Central Europe. Existence and endangerment. AULA, Wiesbaden 1997, ISBN 3-89104-613-8 , p. 295.

- David L. Leonard: Three-toed Woodpecker (Picoides tridactylus) . In: The Birds of North America, No. 588 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA. 2001

- Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim (Hrsg.): Handbook of the birds of Central Europe. Edited by Kurt M. Bauer and Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim, among others. 17 volumes in 23 parts. Academ. Verlagsges., Frankfurt / M. 1966ff., Aula-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1985ff. (2nd ed.). Volume 9, ISBN 3-89104-562-X , pp. 1116-1130.

- Jochen Hölzinger & Ulrich Mahler: The birds of Baden-Württemberg. Not songbirds . Vol. 3. Ulmer - Stuttgart 2001. S 464 - 468. ISBN 3-8001-3908-1

- Hans Winkler, David Christie and David Nurney: Woodpeckers. A Guide to Woodpeckers, Piculets, and Wrynecks of the World. Pica Press, Robertsbridge 1995. ISBN 0-395-72043-5

Web links

- Excellent photos and scientifically sound text by Gerald Gorman (English)

- Two very good illustrations of the nominate form

- Factsheet birdlife international; 2004 (PDF file; 246 kB)

- Summary of the research results on the three-toed woodpecker in the Berchtesgaden National Park

- Picoides tridactylus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed on December 22 of 2008.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Picoides tridactylus in the Internet Bird Collection

- Feathers of the three-toed woodpecker